Trump’s victory was for many people a shock moment. It dramatized how close we have moved toward the return of totalitarianism, how prevalent theories of white and male supremacy have become, and how fragile the truth. Like victims in a vampire movie, we grabbed the garlic closest to hand: books by revered humanist writers from the 1940s and 1950s, telling us how to resist.

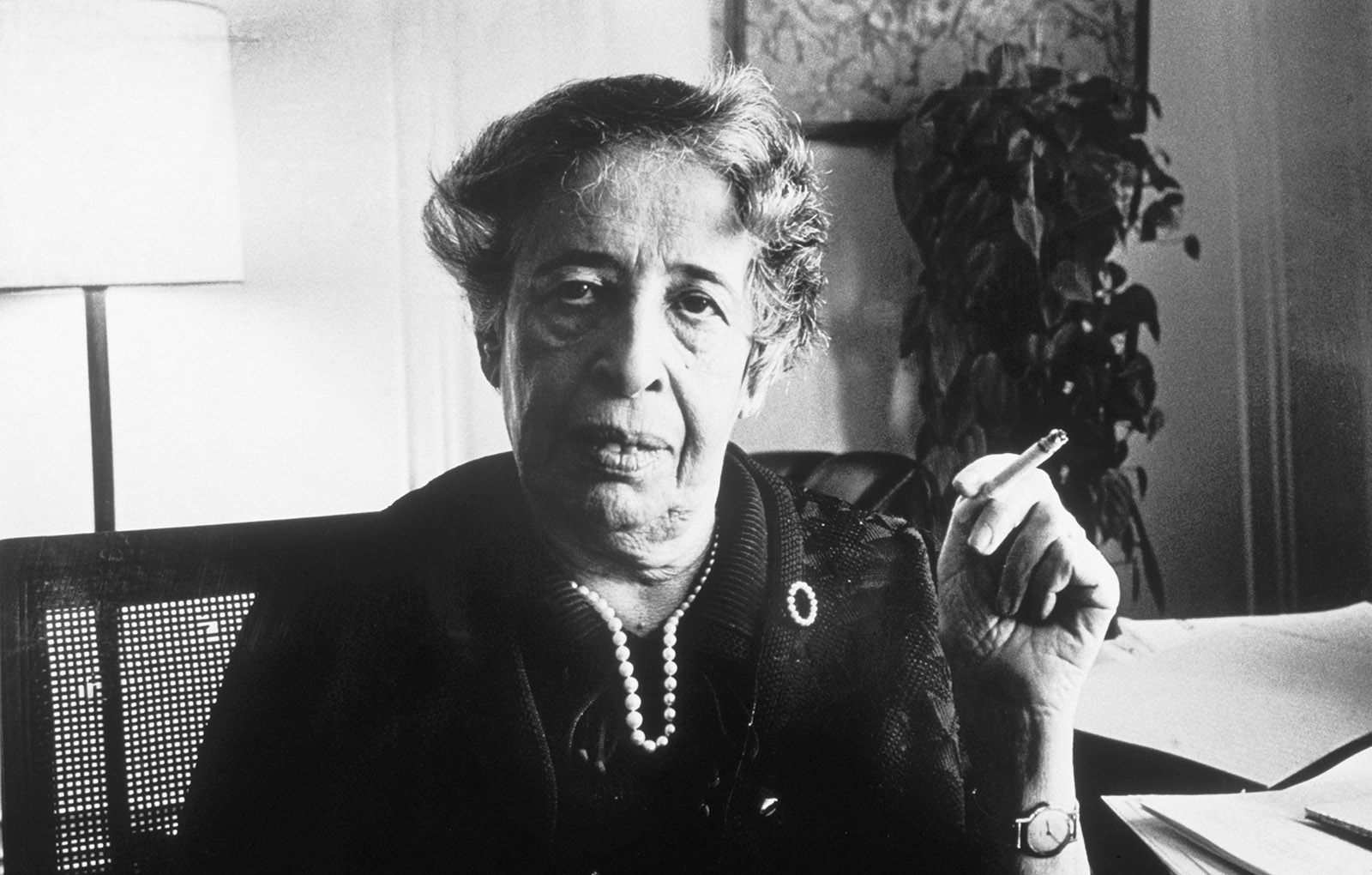

The writings of George Orwell and Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi flew off the shelves. The novels of repentant communist Arthur Koestler and the persecuted Soviet journalist Vasily Grossman were revived. Above all, the work of the German-born political philosopher Hannah Arendt gained huge popularity. In the months after Trump came to power, Arendt became something like the patron saint of liberal angst. Like all these writers, she had been in the postwar decades part of the humanist reaction to the experience of Nazism, the Holocaust, and the cold war.

In 1953, Arendt wrote that “the ideal subject of a totalitarian state is not the convinced Nazi or Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (that is, the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (that is, the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

This was a near-perfect description, sixty-five years in advance, of the electorate shaped by Trump’s rallies, Fox News, and the Kremlin’s secret Facebook ads. What had made people susceptible to fake news in the 1930s, Arendt argued, was loneliness: “the experience of not belonging to the world at all, which is among the most radical and desperate experiences of man.”

That’s the kind of loneliness you experience today in small-town America, or in the left-behind industrial towns of Britain, or the backwaters of Poland and Hungary—all heartlands of the new authoritarian racism. It’s also, paradoxically, the kind of loneliness you can experience in a networked society: How many of the woman-hating and racist mass shooters in America are, after the event, described as “loners” or “lone wolves”?

Arendt’s study of how totalitarianism was spread via sympathizers inside democratic institutions and the mass media also resonates today. Through them, she argued, fascist movements “can spread their propaganda in milder, more respectable forms, until the whole atmosphere is poisoned with totalitarian elements which are hardly recognizable as such but appear to be normal political reactions or opinions.” Today’s right-wing media ecosystem, through which the hardline fascists of the alt-right spread their lies, via the so-called alt-lite websites such as Breitbart into the mainstream channels like Fox News, corresponds exactly to Arendt’s description.

Later, in her report on the trial of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, Arendt coined the famous phrase that could be applied to many of today’s authoritarian kleptocrats: “the banality of evil.” Thousands of Nazi functionaries like Eichmann had participated in mass killing, only to return home each evening to humdrum domestic life. What made them capable of this, Arendt argued, was the loss of their ability to think: “The longer one listened to [Eichmann], the more obvious it became that his inability to speak was closely connected with an inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of somebody else.”

This, in turn, was rooted in the modern bureaucratic lifestyle. Totalitarian states make people into cogs in an administrative machine, Arendt argued, “dehumanizing them.” Worse, she said, this might even be a feature of all modern bureaucracies.

Finally, Arendt understood what it was that could bind together a “temporary alliance of the elite and the mob”: the realization that their ideologies would make sense only if they could reverse historical progress. Both needed “access to history,” Arendt argued, even at the price of destroying the society around them. Today, for both the billionaires surrounding Trump and the “Betas” marching by torchlight through Charlottesville, that is the aim: rewind history and destroy the global order.

Arendt, then, provides important insights even at half a century’s distance. But after 1989, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, it seemed as though the specter of totalitarian systems had gone for good. There were still dictatorships, but they were shabby affairs in countries too poor to support a Nazi-style bureaucracy, let alone practice systematic mind control over their populations. By 2000, when the Bulgarian-French philosopher Tzvetan Todorov wrote his magnificent history of twentieth-century resistance, Hope and Memory, he concluded: “Totalitarianism now belongs to the past; that particular disease has been beaten.”

As we watched the forces that brought Trump to power, we understood that the totalitarian-minded people Hannah Arendt had described have returned. So, as we copied and pasted insights from Arendt into our Facebook pages, and held up her words on placards at anti-Trump rallies, a series of disturbing questions arose.

Advertisement

First: if a successful free-market democracy like the US is capable of producing a Trump, doesn’t that make this moment worse than the 1930s? Hitler and Stalin were the products of state-dominated economies that hit crisis; they led subservient and poorly educated populations, which had been trained by generations of factory work and military conscription to obey the hierarchy above them. Germany had experienced precisely ten years of constitutional democracy in the two centuries before Hitler; before Stalin, Russia had experienced precisely none.

Early twenty-first-century America, on the other hand, is a society full of educated people and with an uninterrupted democratic tradition going back to 1776. For the US to produce a fascist-like mass movement and a kleptocratic attack on the Constitution was not in Arendt’s script.

Second: while the dictators of the 1930s did rely on blurring the distinction between truth and lies, they were greatly helped by their absolute monopoly on information, and indeed disinformation. The elite controlled the printing press and the state controlled the radio stations. Even the possession of typewriters was strictly controlled, both in the Third Reich and the Soviet Union. No such monopoly on information exists today—so what made so many people fall for the Fake News strategy?

Third: Hitler was destroyed by Stalin. The entire postwar world in which Arendt, Orwell, Koestler, and Levi wrote their critiques of the totalitarian mind-set was created by the victory of one totalitarian state over another. If the West is today under threat from a resurgent totalitarian impulse, where is the external force capable of smashing it, as the Allied and Soviet armies did in 1944–1945?

The paradox of today’s cult of Arendt is that, among all the anti-authoritarians of that era, her thought is the least equipped to help us answer those questions.

Orwell and Koestler fought fascism in Spain—Koestler as a card-carrying communist, Orwell as a member of the far-left POUM militia. Levi fought as a partisan in 1943, in a group allied to the liberal-socialist Partito d’Azione. Grossman, the first Soviet journalist to enter the remains of the Treblinka concentration camp, had served throughout the war as a Red Army journalist. Every one of them understood they were morally compromised by the antifascist war they had taken part in.

Levi’s partisan unit disintegrated after they were forced to shoot two volunteers for indiscipline. Koestler’s portrait of a ruthless Soviet commissar was based in part on his own actions as a Comintern spy. Grossman had denounced other writers and managed to report the Red Army’s advance across Europe without public mention of its mass rapes and massacres. Orwell’s poem, “The Italian Soldier,” about an anarchist volunteer in the Spanish Civil War dramatized the problem of fighting fascism in alliance with Stalinism. “The lie that slew you is buried,” Orwell wrote, in a bitter eulogy to his presumed-dead comrade, “under a deeper lie.”

Each of these writers committed violence in the name of antifascism. In their work, antifascist violence is seen as inevitable, if tragic—and leads ultimately to the strengthening of Stalinism, bureaucracy, or inhuman attitudes. Although she was detained for political opposition to the Nazis in 1933 and had to escape from France after they invaded, arriving in the US in 1941, Arendt committed no antifascist violence.

Practically, Arendt solved the problem of fascism versus Stalinism by escaping to America, an achievement nobody could begrudge. Theoretically, however, she solved it by claiming that American constitutional democracy was a form of industrial society uniquely immune to totalitarianism. In her 1948 lecture to a socialist club in New York, Arendt outlined a clear theory of American exceptionalism from totalitarian tendencies:

The American Republic is the only political body based on the great eighteenth-century revolutions that has survived 150 years of industrialization and capitalist development, that has been able to cope with the rise of the bourgeoisie, and that has withstood all temptations, despite strong and ugly racial prejudices in its society, to play the game of nationalist and imperialist politics.

The US, Arendt claimed, was a twentieth-century democracy that “lives and thrives” by an eighteenth-century philosophy—that is, the utilitarian Protestant individualism written into the Constitution. The practical role of the philosopher was to improve US society by criticizing it, as she would do over Civil Rights and Vietnam.

Arendt was a courageous opponent of tyranny, but instead of deifying her, we should understand her ideas in their time. Nazism, she said, had emerged out of the “vacuum resulting from an almost simultaneous breakdown of Europe’s social and political structures.” When the Nazis said that the old order had collapsed, they were, in this sense, simply “lying the truth,” as she put it.

Advertisement

But Arendt never explained why Europe’s social and political structures broke down. She preferred to describe innate tendencies toward evil, in the subterranean culture of antisemitism, or imperialist white supremacy, that “crystallized” into Nazism and Stalinism. But crystallization is a physical process with cause and effect. If you are looking for an explanation of what caused the similarity between Nazism and Stalinism, look elsewhere: Arendt was a theorist of “What’s gone wrong and how should humans live?”—but not “What’s happening, and why?”

The assumption that Arendt was the first person to identify the common features of the totalitarian projects of Nazism and Stalinism is nonsense. Of all the people she mixed with, and whose work she would have read in America in the 1940s, she was the among the last to make this connection.

Throughout the 1920s, anarchists and socialists from the anti-Bolshevik tradition had warned that the Russian Revolution had the potential to create a dictatorship, mirroring the worst of what had happened in the West. When they considered the source of this danger, they located it in the “backwardness” of Russian society, or the uneducated level of the peasantry and the working class. When industrial-scale lying and oppression took off, with the ascendancy of Stalin’s faction from 1927, it was thinkers from the socialist and communist traditions who first proposed that this might signal the emergence of some new system, rooted in technological progress and the bureaucracy of modern states.

The Austrian socialist Lucien Laurat proposed in 1931 that the USSR was neither capitalist nor socialist, but “bureau-technocratic”: a new ruling caste had seized control and imposed a new form of class society. Laurat explicitly connected this to the emergence of managerial bureaucracy in Western countries, creating “another form of exploitation of man by man” to replace capitalism.

By 1937, the Soviet Union was practicing industrial-scale murder. The Moscow show trials were merely the shop window for a vast purge that would, in the space of just two years, kill an estimated 1.2 million people—mainly left-wing communists, militant workers, political oppositionists, and army officers deemed likely to side with them.

It was in the aftermath of the Moscow trials that an oddball left-winger named Bruno Rizzi published a book entitled The Bureaucratisation of the World. In it, he argued that the Soviet bureaucracy was simply a Russian expression of a new form of class society that was replacing capitalism all over the world: “bureaucratic collectivism,” he called it. Rizzi proposed that in Russia, Germany and America this new bureaucracy had replaced the proletariat in driving historical progress. Both Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, Rizzi said, had acquired an anticapitalist character: “the social character of their countries is the same.”

When Hitler and Stalin signed their peace pact in August 1939, dismembering Poland and leaving Germany free to wage war on Britain and France, Rizzi’s bureaucratic collectivism thesis took off powerfully inside the Western left. James Burnham, one of Trotsky’s leading followers in the US, declared the USSR, Nazi Germany, and Roosevelt’s America to be three kinds of “a new form of exploitative society.” This “managerial revolution” was destined to triumph everywhere, leaving historical progress with no option but to operate through the actions of totalitarian dictators. Compared to Arendt, whose 1951 study The Origins of Totalitarianism was criticized for being softer on Stalinism than Nazism, Burnham’s theory was clear: the two are exact equivalents.

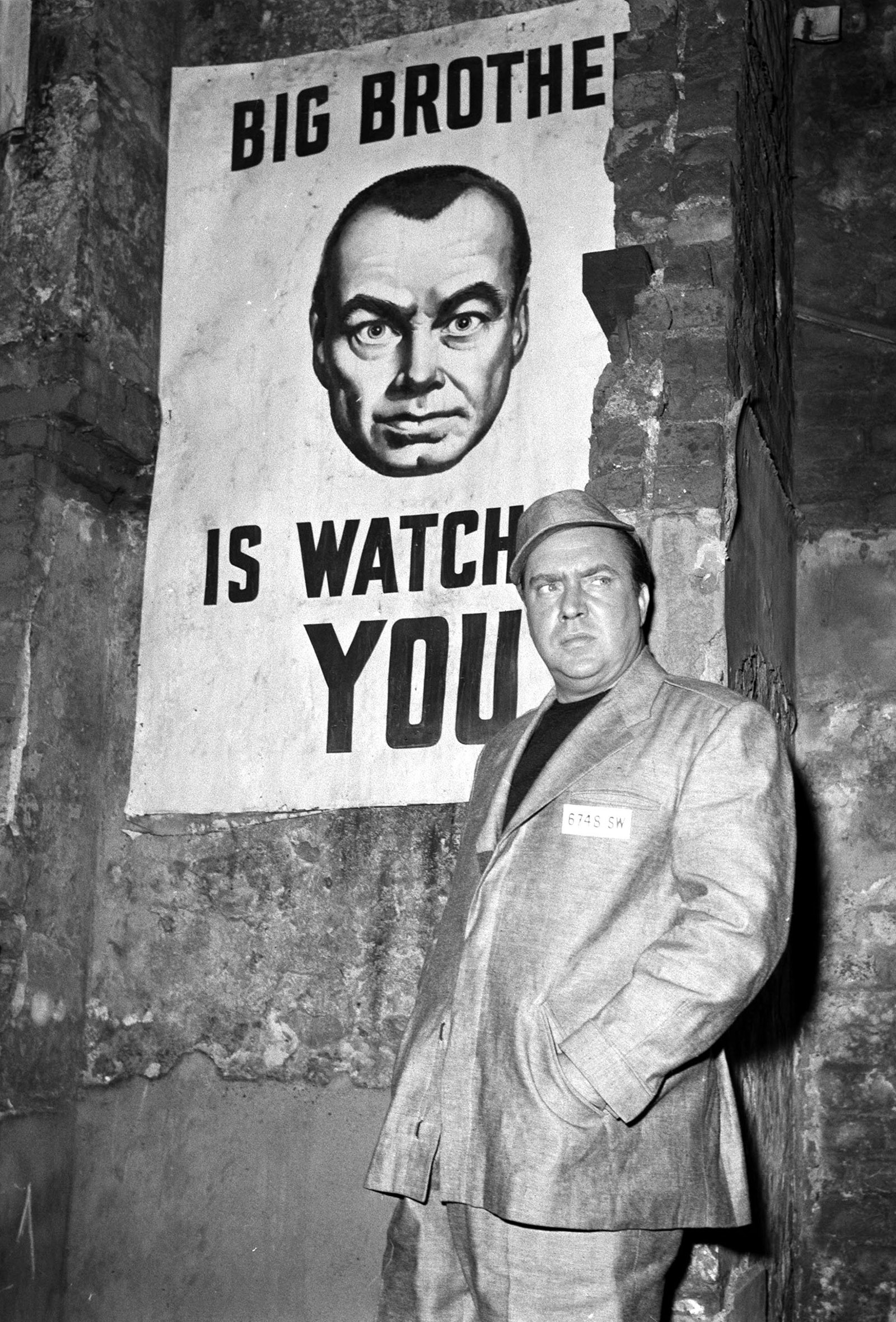

In George Orwell’s masterpiece, Nineteen Eighty-Four, it is Burnham’s ideas that are parodied in The Book, the secret manual of the underground movement trying to overthrow Big Brother. Orwell rejected Burnham’s claim that the world was about to become three unmovable totalitarian dictatorships, but explored—by way of a warning—how it might come about: by suppressing all knowledge of the past; by turning language into political jargon so that people can’t think rebellious thoughts; and by repressing sexual desire.

Orwell’s hero, Winston Smith, does find out about the past. He maintains a critical private language in his diary. And he most certainly follows his sexual desires. But he is captured by the ingenuity of the ruling party, which has created a fake opposition leader, Emmanuel Goldstein, modeled half on Trotsky, half on Burnham, to entrap anybody who rebels.

These ideas—circulating from Rizzi to Burnham to Orwell—had been current for more than ten years when Arendt wrote The Origins of Totalitarianism. What distinguished Arendt, then and later, was her refusal to explain why totalitarian ideologies triumph. “There is an abyss,” she wrote, “between men of brilliant and facile conceptions and men of brutal deeds and active bestiality, which no intellectual explanation is able to bridge.”

If we are going to use Arendt as a guide for today, this conceptual void is a big problem. It is one thing to say that in the late 1920s the old European society collapsed and left a vacuum. The question that event posed was this: Why was that vacuum filled with such extremely similar ideologies and actions focused around inhumanity, death camps, organized lying, torture, and the suppression of rational thought and language?

The missing idea in Arendt’s thought was class. She correctly identified the brutalities of fascism as originating in those of late-nineteenth-century colonialism. She borrowed an idea from the Polish Marxist Rosa Luxemburg—that European states needed to export their excess savings and populations to their colonial possessions. She understood that imperialism created the material basis for an alliance between the “elite and the mob,” based on master-race theories; and that fascist movements were composed of people among both rich and poor whose interests suddenly converged on the collapse of the old order. Arendt also was right to point out that the reformist socialists in pre-1914 Germany overlooked the dangers of working-class fascism because it didn’t fit into their theories of class struggle.

But Arendt failed to understand the class dynamics of the societies that produced both fascism and Stalinism. The working-class revolts of the early twentieth century, and their failure, account for almost everything that Arendt chooses not to explain about the rise of totalitarianism.

With fascism—in Italy, Germany and Spain—it is the inability of the capitalists to go on buying off a layer of workers, and the sheer size and social power of the radicalized labour movements, that obliges the elite to rely on militarized right-wing groups to smash the unions and the socialist parties. With Stalinism, it is the backwardness of Russia, the isolation and atomization of the working class after three years of civil war, which by the mid-1920s allowed a new class of bureaucrats to take the place of the old bourgeoisie.

Unless you really understand that working-class self-organization was the specter haunting the European elite—from the global mass strike movement of 1911–1913, right through to the defeat of fascism by communist-led uprisings in 1943–1944—you cannot understand why that elite became so prone to supporting fascism in the mid-twentieth century.

Today’s events, however, pose questions that Arendt’s methodology is even less suited to answer. Neoliberalism’s collapse has stripped the current model of capitalism of all meaning and justification. Even in Arendt’s beloved “American Republic,” the vacuum is being filled by an ideology hostile to human rights, to universalism, to gender and racial equality; an ideology that worships power, sees democracy as a sham, and wishes for a catastrophic reset of the entire global order. Worse, the number one weapon for the US right is that self-same “eighteenth-century philosophy” that Arendt assumed had given Americans immunity from totalitarian rule: their individualism, which has been turned against them during thirty years of free-market rule, and their belief that economic choice constitutes freedom.

Arendt, in a phrase that still resonates, said that “what the mob wanted… was access to history even at the price of destruction.” As we observe the alt-right militias of the United States, openly carrying guns and uttering death threats against feminists, leftwingers, and migrants, it is hard not to conclude that destruction, yet again, is their deepest desire. Collapse everything and start again is the modern right-wing fantasy.

Yet today’s “mob” lives in the richest country on earth. A place in which their rights to carry guns, protest outside abortion clinics and spout racist bullshit are unconstrained. And a nation that is nearly a decade into an uninterrupted economic recovery. Why do they want to destroy it?

If Arendt’s descriptions of the dynamics of totalitarian movements hold good—and they largely do—her explanations for them do not. As a result, if Trump has triggered a crisis of progressive thought, it is in particular a crisis for the cult of Hannah Arendt. The United States of America was her last and enduring hope: the only political institution on earth that was supposed to be immune to totalitarianism, nationalism, and imperialism.

Arendt’s humanism was based on “what ought to be,” not on what is. Human beings, she wrote, should resist totalitarianism by trying to live an active life of political engagement, and by carving out freedom to think philosophically.

But no matter how many progressive causes she espoused, hers was a worldview tainted by admiration for the reactionary German tradition in philosophy begun by Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche taught the German bourgeoisie of the late nineteenth century that its fantasies of empire and volk were more valid than the working-class project of collaboration, equality, and a human-centered society. Morality is a sham, he said, and the most honest thing to do is to pursue your own self-interest by any means necessary. There is no purpose to human existence, such as the “good life” imagined by Aristotle, and so no set of morals or ethics can be derived from it.

Although Arendt lamented the way bourgeois morality “collapsed almost overnight” under Nazism, her explanation for this event was, essentially, that Nietzsche had been right: his “abiding greatness” lay in demonstrating how shabby and meaningless the morality of the German bourgeoisie had been exposed as, she wrote.

Nietzsche would become the cult figure of neoliberalism. Once human beings are reduced to two-dimensional, selfish, and competitive individuals—in a world where “there is no such thing as society,” as Margaret Thatcher once put it—the only logical response is to cast yourself as one of Nietzsche’s supermen: the alpha male, the ruthless manager, the financial shark, the pick-up artist.

Arendt certainly drew different moral conclusions from those of Nietzsche, but she could never see him or the philosophical tradition he gave birth to as the progenitor of Nazism. Indeed, she went out of her way to absolve him of responsibility for Hitlerism. To her dying day, she remained in awe of Nietzsche’s leading pro-Nazi follower, and her one-time lover, the philosopher Martin Heidegger.

For us, understanding the philosophical through-line from Nietzsche via Hitler to the American neocons of the Iraq era and the alt-right of today is critical. Nietzsche is the all-purpose philosopher of reactionary politics. He says to the middle-class mind, dissatisfied with managerial conformity, that there is a higher form of rebellion than the one proposed by socialists, feminists, and other progressives: an individualist rebellion against morality, in favor of oneself.

He tells the elite that elites are necessary, and he is brutally honest that this demands a form of social apartheid in which most people perform “forced labor.” He decries state intervention, just as the modern right does, and advocates “as little state power as possible.” He is appalled, of course, at the possibility of working people using taxation to redistribute wealth. Nietszche, instead, idolizes the “criminal type”: all the gangster lacks to be a superhero, he says, is “the jungle, a certain freer and more dangerous form of nature,” in which he can demonstrate that “all great men were criminals and that crime belongs to greatness.”

Nietzsche greeted the rise of European imperialism with the words: “A daring master race is being formed upon the broad basis of an extremely intelligent herd of the masses.” What that master race needed was freedom from social norms and religious morals, so that they could become “the kind of exuberant monsters that might quit a horrible scene of murder, arson, rape and torture with the high humor and equanimity appropriate to a student prank.”

Any reading of what Nietzsche actually said, in the context of the rise of the German labor movement and the birth of German imperial ambition, should leave any humanist, democrat, or supporter of human rights reeling in disgust. But he did not repel Arendt.

Why does this matter? Because, if we want to trace the thread that links the barbarity of the colonial period, the widespread adoption of irrationalism among European intellectuals in the 1920s, the rise of the Nazis to the rise of the modern-day alt-right, it resides, above all, in this doctrine of amoralism and biological supremacy advocated by Nietzsche.

The Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre once wrote that there is something logical in the repeated rediscovery of Nietzsche and his superman theory. Whenever the capitalist order comes under stress and the rule of the elite is challenged, the ordinary morality that rich people profess is called into question. Repression, deviousness, lies, and even murder become the order of the day. At these critical moments, the ordinary, boring bureaucrats discover that their norms and morals were just a jumble of old rules without any logical underpinning. Because of this, wrote MacIntyre, “it is possible to predict with confidence that in the apparently quite unlikely contexts of bureaucratically managed modern societies there will periodically emerge social movements informed by just that kind of prophetic irrationalism of which Nietzsche’s thought is the ancestor.”

That is exactly what we are living through now, and Arendt’s thought cannot explain it—because she refused to understand fascism as the elite’s response to the possibility of working-class power, or to understand the essential role of irrationalism in all such reactionary movements, and because hers was a philosophy based on American exceptionalist assumptions of immunity to totalitarian impulses. This is sadly disproved.

Arendt’s optimism about postwar America stemmed from her belief that people can learn to take self-liberating actions, learn to distinguish good from bad, and the ugly from the beautiful. But if you share her optimism—and I do—then you are now up against a very dangerous opposing force.

In this context, the rediscovery of Hannah Arendt and the humanism of the 1950s is not enough. We need a humanism that can resist the re-establishment of biological hierarchies and root instead the universality of human rights on more solid foundations than the ones currently under attack. This project will need to survive contact with the new challenge of thinking machines and the new ideology of machine control known as post-humanism.

This essay is adapted from Clear Bright Future: A Radical Defence of the Human Being, by Paul Mason, published by Allen Lane.

An earlier version of this essay gave 1951, the original publication date of The Origins of Totalitarianism, as the year Arendt wrote about “the ideal subject of a totalitarian state [etc.].” In fact, that sentence was from a journal article first published in 1953, and only later included in subsequent editions of The Origins of Totalitarianism. The article has been updated accordingly.