A file of young women in décolletage-baring black cocktail dresses and wobbly stilettos makes its way through the mêlée of Trafalgar Square, dense with football fans. They kick aside the empty beer cans that litter every passage. At their tail is a slightly bedraggled woman in white. A beauty queen’s sash across her chest spells out “Bride-to-Be.” As I walk down the Duke of York Steps and turn into The Mall with its stately Nash Buildings, their stucco whiter than the bride-to-be’s frock, I imagine a smile on the iconic face of the New York writer, performer, and member of the 1970s and 1980s Manhattan downtown avant-garde whose work has now inspired a show at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), “I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker.” The hen-party scene elevated to a surreal extreme could have come out of one of her books.

Acker made London and the ICA—the cultural center founded in 1947 by Roland Penrose and others as an alternative to the stuffy confines of the Royal Academy and, since 1968, situated somewhat incongruously on The Mall just down the road from Buckingham Palace—her sometime base from the mid-1980s before her too-early death at the age of fifty in 1997. Acker liked subverting bridal white and other tropes of female submissiveness, alongside conventional forms of female desire. All the while, she inquired into the power of capital and colonialism (not to mention cock) that had established them.

It’s no surprise that Acker, who had the aura of a punk star and performed her readings with a slow, flat earnestness that utterly belied their often shocking content, felt at home at the ICA, an arts institution where the various forms—music, writing, dance, theatre, visual art, comics philosophy, film, high culture and popular—crossed over and mixed and mingled, as did their audiences. I worked there through the 1980s, initially programming the literature and ideas side of things. At once or in sequence, we might have had Jacques Derrida, Julia Kristeva, and Stuart Hall in the building, or Salman Rushdie, Angela Carter, and Kazuo Ishiguro, plus, say, an early theater piece by the innovative Théâtre de Complicité, DJs presenting the hottest new groups, and a seasonal show of New York artists.

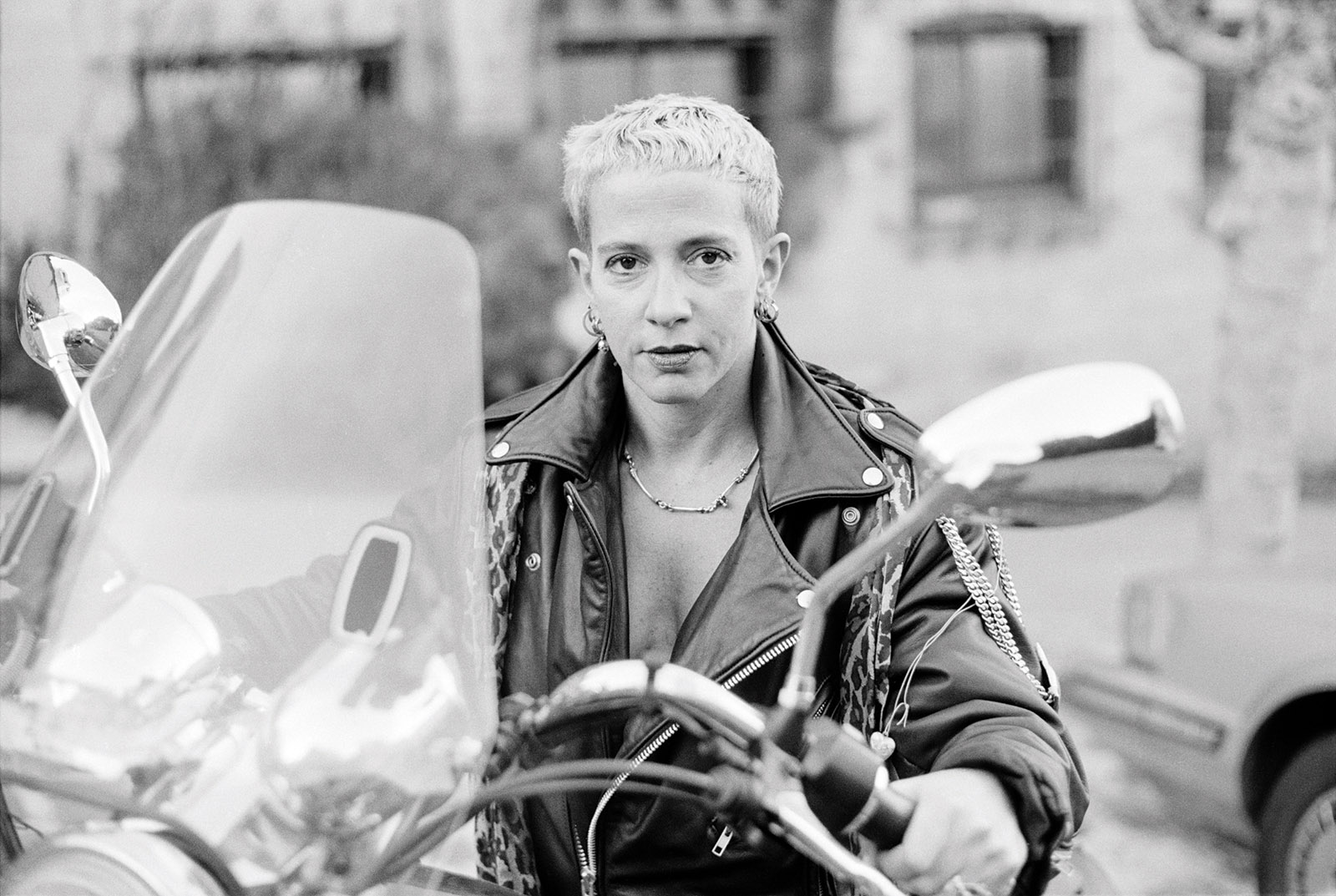

Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Frank Stella, and Robert Mapplethorpe all came through the ICA. The latter had photographed the gamine Kathy Acker in 1983, elbows almost covering bare bosom, hands over eyes, transforming her into a perverse bloom, the kind that Jean Genet—whom she admired—might have written about, if weights and gyms had been his thing. In other photos, she appears in close-up, round brown eyes intense against baby-soft skin like a Renaissance cherub—one with an urchin’s cropped hair, piercings, tattoos, and the dangling single earring of a pirate.

At the ICA, Kathy talked about and performed her work: her gigs, the edgy danger of her texts with their direct language and profanity, disseminated her art-world fame. She also enjoyed interviewing writers such as her mentor William Burroughs, Scotland’s Alasdair Gray, or the sociologist and sometime novelist Richard Sennett. She did all this with a respectful seriousness. In 1985, her play Lulu Unchained, a retelling of the Wedekind/Berg opera, produced by Michael Morris, opened at the ICA, not altogether successfully. It’s interesting to note that Angela Carter, who shared some of Acker’s preoccupations but who was a very different, though equally radical writer, also attempted a play about Lulu—that emblem of a polymorphous female sexuality so innocently powerful as to be, inevitably, killed off by the hostile male power it attracted.

Now, Acker is back at the ICA in an exhibition whose very title echoes her strategic play with multiple personae, as well as her status as an experimental exemplar of what today we would call autofiction. Whether Acker took on the guise of Don Quixote, Dickens’s orphan Pip in Great Expectations, or Toulouse Lautrec, overtly plagiarizing chunks of text as she went, she was also always that other, perhaps more intimate persona that she documented in her work: the poor-little-rich-New-York girl, whose father left before she was born, whose mother hated her, and who grew both to live and fantasize brutal pornographic encounters while longing for love and for feeling itself.

Acker was nothing if not a mistress of the contradictions of being woman, a post-punk amalgam of de Sade’s masochistic Justine, virtuous in her enforced prostitution, and his triumphant libertine Juliette. If her evocations of (sexual) violence against women make her, in some senses, a precursor of millennial feminism, her plaint or critique was less aimed at individual male malefactors than at the system of patriarchy as a whole. As for individual embodiments, she needed them as objects of desire or desiring. Her transgressiveness and frank avowal of desire was radical at the time, but in ways that don’t necessarily track comfortably with contemporary feminisms. It may well be that the current interest in her work is as much to do with her emphatic use of the first person—even though that person is ever the artist: a shape-shifter whose identity and sexual desires don’t fall neatly into prescribed or given locations, then or now. “I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker,” indeed.

Advertisement

By her own account, she came to feminism after a stay with the Black Mountain school of poets. An education in structuralism and poetry left her with no credentials for work, she claimed—except for working in a sex show. Thrown onto the mean streets, she became politicized.

The ICA’s adventurously curated exhibition extends over two humming floors packed with blow-ups of Acker’s texts, videos of her performances—mesmerizing in their delivery—pictures of her (a glorious one showing her tattooed and muscled on motorbike), parts of her book collection displayed in vitrines, even her well-worn Vivienne Westwood pirate jacket. All this is counterpointed with work by artists of her own time through to the present whose art resonates with hers. There’s an exciting sense here of a William Burroughs’s cut-up—the writer who, along with the picaresques of Jack Kerouac, perhaps most influenced Acker. “I, I, I, I, I, I, I” uses juxtaposition deftly to produce unexpected echoes of meaning. Affinities and connections have a random but revealing feel.

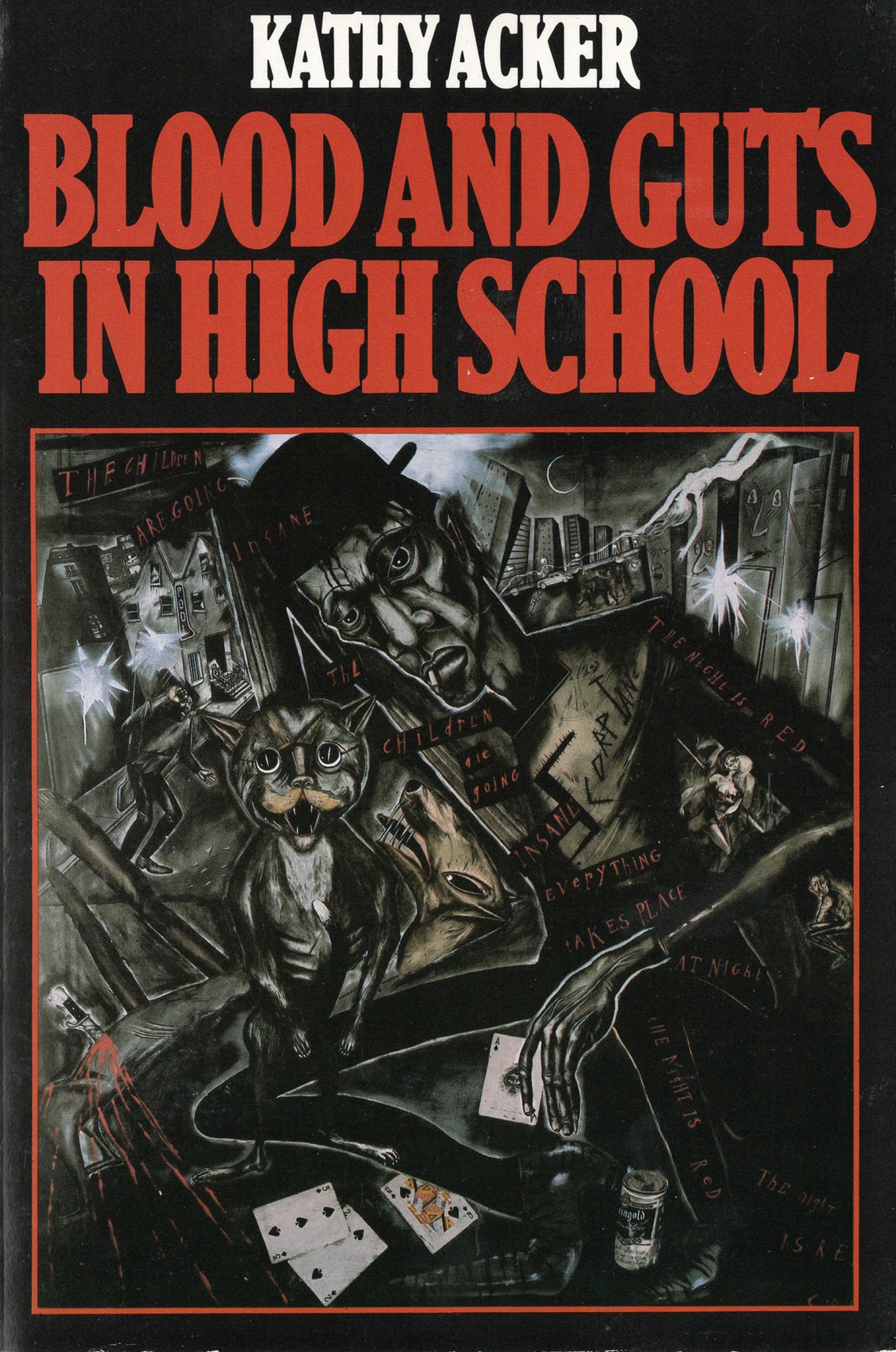

The show begins by mapping the movements of Acker’s literary output, from magazines and small press pamphlets or mail art—she posted an early run of 600 copies of The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula to eminent writers and artists—to full-length commercially published books, first in line being her compendious 1984 novel Blood and Guts in High School. She recycled her work, cut it up differently, added, so that the arrows on the wall depicting its circulation resemble flight path maps, with artfully produced journals, pamphlets, or plays, stopping points on a dizzying route.

My eyes fell on “Schizo-culture,” a 1978 edition of the journal Semiotext(e), in which Kathy Acker’s name appears first in a list including John Cage, Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, and others. I was curious to see how the historian and philosopher Foucault, whose annotated volumes from her library are on display, intersected with Acker. This was the journal’s antipsychiatry issue, sparked by a conference, and contains an interview with Foucault about Bentham, the panopticon and surveillance culture—in prisons, madhouses, asylums, and factories. Acker’s contribution was The Persian Poems, complete with a Farsi original: “to know / have / buy / want / see / come / beat up / eat / rob / kidnap / kill / know…”—which can read as shorthand for Acker’s abiding concerns. The connection with Foucault underscores the fact that Acker’s writing, for all its sensationalism, is also about surveillance, Foucault’s “eye of power”: turned on women, it imprisons them in sexual, reproductive, or familial modes. Internalized or not, it maddens them, and in the process also addicts them to being seen, to the terror of becoming invisible.

The connections the exhibition sets up as it moves from one Acker text and moment to another are intriguing and often witty. Her blown-up fragment from The Childlike Life of the Tarantula, drawing on de Sade and others, leads to 1970s gelatin prints by Jimmy DeSana: one showing an eerily erect mummified woman, the other a near-naked figure stuffed into a refrigerator. A volume of Antonin Artaud from Acker’s personal library finds an echo in the American artist Nancy Spero’s Codex Artaud XXV of 1972, a painting and collage on paper with an image of a man’s head, complete with phallic tongue beneath menacing birds and bomb, above scraps of text from Artaud, reading “terriblement inquiet” (very anxious).

Further manifestations of an Acker-esque imagination abound. All along the large downstairs gallery an aluminum pipe, like a reject from Paris’s Pompidou Center, winds its way along the ground, a recent piece by Swedish-born artist Ghislaine Leung, VIOLETS 2 (2018). In an upper gallery, a “Hormonal Fog” machine by Candice Lin and Patrick Staff (2016–2018) is working—every so often belching out a foul smell. Nearby, there’s a bright, childlike Tree of Life sequence of magic-marker drawings by the punk musician Genesis P-Orridge with whom Acker performed. The subversive “political dominatrix” Reba Maybury, side by side with Acker’s annotated Venus in Furs, exhibits a raunchy comic strip called The Goddess and the Worm, in which a woman erotically tortures a worm.

Advertisement

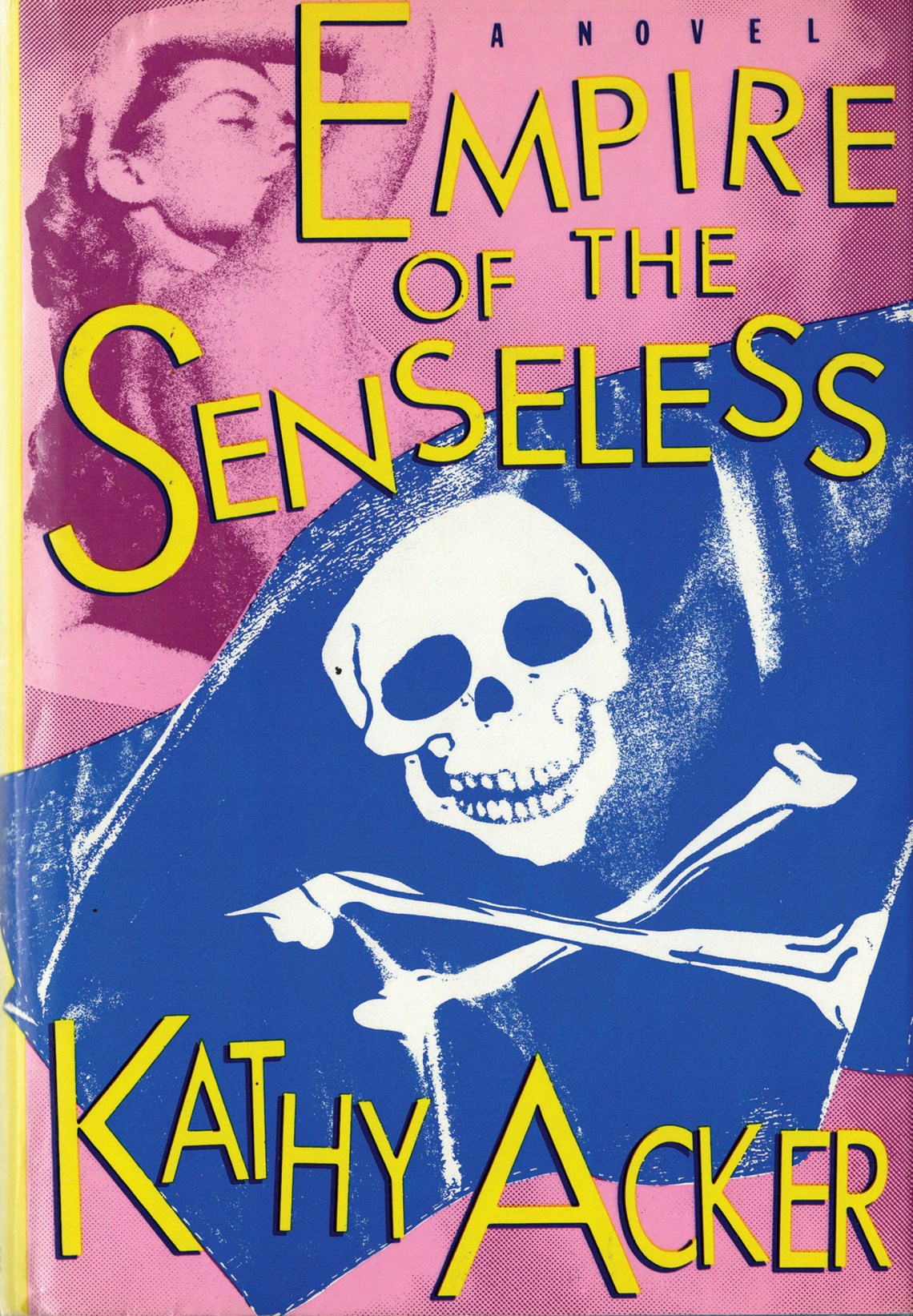

Upstairs, alongside Acker’s embodiment as the nineteenth-century “damned” poet, Arthur Rimbaud, in her In Memoriam to Identity (1990), we see images by her contemporary the photographer David Wojnarowicz, himself wearing a Rimbaud mask, shooting up in a dark alley, capturing down-and-out life in Manhattan. Opposite is a Beardsley-like sequence of drawings of drug-taking and copulation by the Glasgow artist Jamie Crewe. In another room, with Acker’s 1996 book Pussy, King of the Pirates, is a large poster depicting the unicorn-ed figures that heralded the Australian art collective VNS Matrix’s 1991 Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century.

Acker wrote Pussy the year before she died of cancer. By then, her inherited money had run low and conventional medicine was forbiddingly expensive, so she had sought alternative treatment. Her focus on a dangerous girl gang of sex-positive feminist pirates and prostitutes is a celebration of desire so rampant in its quest for transformation and transcendence that it seeks to overthrow that “skanky-skunk-wood-tangled-garbage-whatever-it-was called nature.” Where gender identity is concerned, that may be possible. Death, sadly, paid little attention. Now, a new generation, sparked by her gender fluidity and her dramatic texts, is re-inventing her as their own.

“I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker” is at London’s ICA through August 4.