In Veronica Gonzalez Peña’s fascinating new documentary about the painter Pat Steir, which premiered at the New York Jewish Film Festival earlier this year, Steir recalls an interview with the philosopher Sylvère Lotringer in which he remarked: “When I look at your work closely, I feel that your entire career has been a long effort to disappear.” “It’s true,” Steir says in the film, adding that she has been “trying to take my ego out of the art and my body out of the art. I want the paintings to express something in the will of nature.”

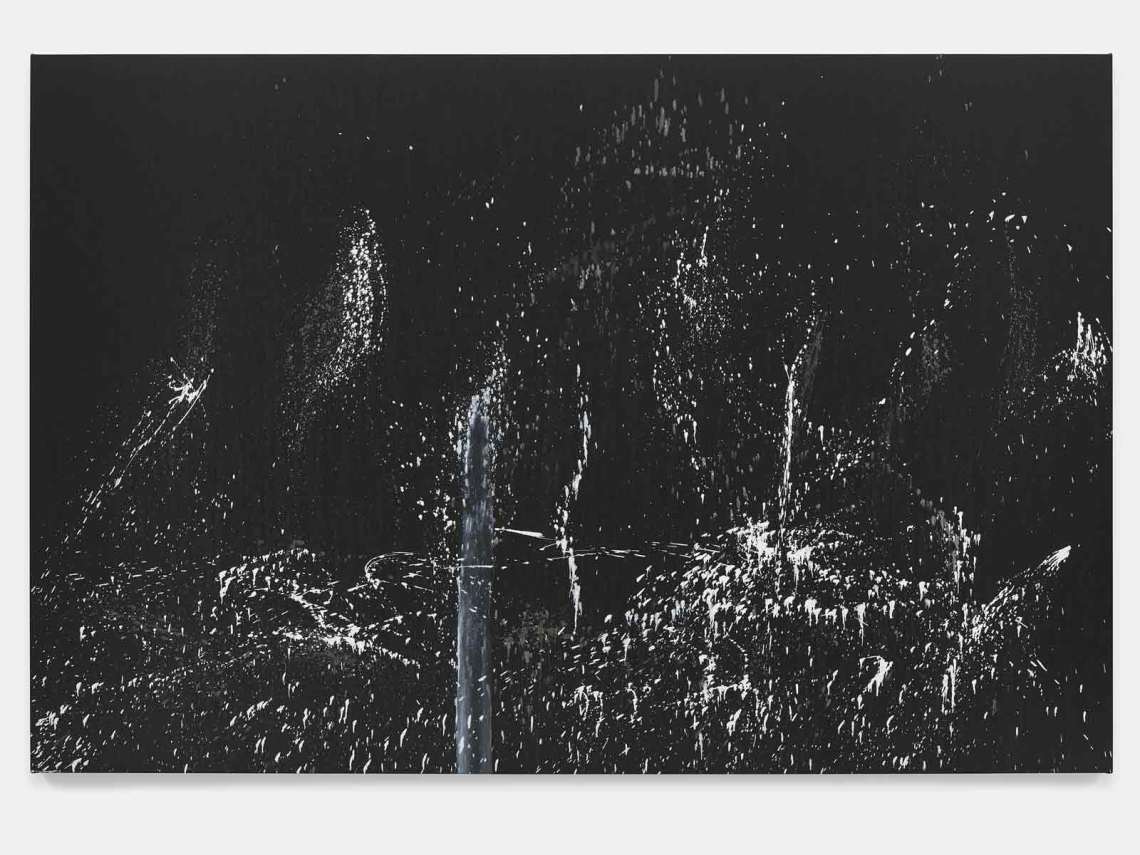

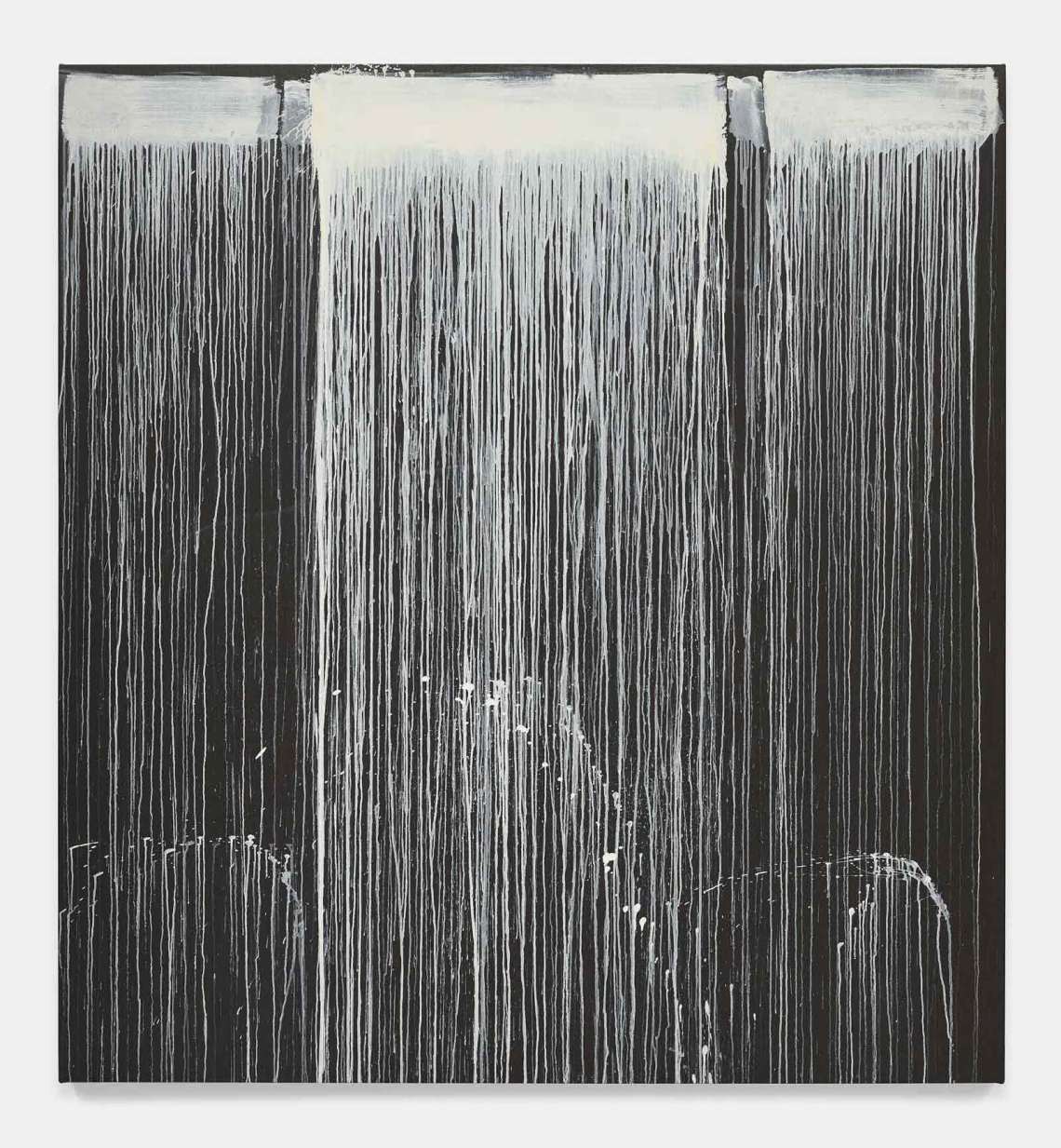

In much of her work, Steir—whose latest paintings are on view in the exhibition “Pat Steir Silent Secret Waterfalls: The Barnes Series,” at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia until mid-November—applies a mass of oil paint to the upper part of her canvases, many of which are taller than herself, then lets it drip. Or she throws paint at the surface, letting the marks happen by accident or by a process we might call random design. “My idea,” she says in the documentary, “was not to touch the canvas, not to paint, but to pour the paint and let the paint itself make a picture. I set the limitations. The limitations, of course, are the color, the size, the wind in the room, and how I put the paint on. And then everything outside of me controls how that paint falls. It’s a joy to let the painting make itself. It takes away all kinds of responsibility.”

Born in 1940, Steir grew up in Newark. She studied at the Pratt Institute—Philip Guston was one of her teachers—and at Boston University College of Fine Arts and began painting in New York, where she also worked as an illustrator and book designer. The documentary takes us through the associations that have influenced her art in the past half-century, especially her friendships with John Cage, Sol LeWitt, and Agnes Martin, whom she visited in New Mexico every August for thirty years. Courtesy of these relationships, Steir became interested in lessness, erasure, the idea of the aleatory image, the space between the deliberate and the unstructured, the image eventually emerging through a sort of chance.

As she talks about her work, Steir sometimes sounds tentative, ironic, or amused; but when she discusses technical matters—how a color was mixed or a texture created—she is confident and sharp, brilliant and quick. When she speaks about being a female artist, and the different ways in which male and female artists are seen and valued, she makes clear how great the struggle has been. “Now I’m over seventy so I’m like an honorary man,” she says; she remembers with indignation a gallerist in New York with many female artists on his books who had said, years ago, “I can get high quality for a low price if I deal with women artists.”

In the Annenberg Court of the Barnes Foundation (the large space where people line up to see the permanent collection), Steir’s monumental black-and-white paintings—all seven feet tall and ranging from about five to seventeen feet wide—cover three walls. These eleven “Silent Secret Waterfalls” enact the falling of water, and the idea of water as having its own internal power; but they also enact the falling of paint—the great, luminous whiteness that Steir allows to have its own inner life. She is more concerned with essences than with experiences, more interested in what the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called inscape than she is in landscape.

While it should be possible for someone looking at these paintings to feel that they depict or suggest the flowing of water downward over rock or stone, that is to miss the point of works that are concerned much more with the potential of paint than the need to represent something in nature. They are, to a large extent, autonomous spaces, powered by the visual possibilities of chance and flow. This may connect them to nature: they do what a waterfall does. They have some of the same force. But as paintings, they are dynamic rather than completed; they happened by an arranged accident, the surface is not settled, it is often fully free, moving beyond the natural phenomenon of the exhibition’s title and reaching into the realm of the visionary.

Each painting makes no secret of how it started. You can see the place toward the upper part of the work where Steir used a brush to apply the dripping oil paint to the canvas. What is mysterious, as you look at the different ways in which the paint flowed down, is how much she could judge the extent and direction of the flow or how much the direction of the paint depended on chance. It is miraculous how beautiful this white paint against a black surface appears, how fluid, how oddly patterned and animated with energy.

Advertisement

Steir’s journey toward the making of the “Waterfall” paintings began in the 1980s, when she was paying close attention to Japanese woodcuts and Chinese brush painting. “The Waterfall paintings,” she told Gonzalez Peña, “were everything I hoped my paintings would be…. The less I tried, the better the paintings were. The more I tried, the more controlled and stiff they got. In the ‘Waterfall’ paintings, the paint made the images.”

Steir has the ability to leave a painting alone, not to fiddle too much with contours and edges. But there are times when small details carry a strange emotional charge. In one of the widest paintings at the Barnes, the paint flows as in the others, making a number of different patterns, patterns that, as the paint moves down the canvas, created a great drama of whiteness—unstable, undecided, unsettled. If you stand back, studying the purity of the flowing white paint against the black background, there is a sense of grandeur about the work. But, as you move closer, the smaller details seem to matter as much as the larger pattern.

There are, for example, five or six very thin vertical white lines near the center of the canvas, like wrinkles or stray marks, each no more than an inch or two in length. Against the sheer drama of flowing paint going on around them, these marks might seem like afterthoughts. But the more you look at them, the more they pull your eye in further, the more enigma and emotion they seem to contain. They are like nothing, and yet they offer us an image of frailty against the strength and the rush of what is going on around them.

In the last of the eleven paintings, the work is offered a deliberate structure by the inclusion of fifteen horizontal white lines, the ones at the top almost straight, the lower ones more jagged. Just above the top line at the right of the painting, Steir lets paint the color of thinly spilled milk spill down. Along the fourth line, from left to center, she allows three further spillages, each a different shape and density. In the space between the middle four lines, she has made tiny squiggles that run right across the painting, giving it a fixed center that the other paintings, for the most part, do not have.

When I visited on a winter afternoon, three paintings in the corner were caught by sunlight from a long thin window. Marks that seemed white suddenly appeared as silver; the sun made the paintings even more mysterious in their evanescence. Although her work represents what Steir calls “many moments accumulated,” she seems determined not to mask this by the suggestion of something spontaneous. What is affecting about her work is this sense, on the one hand, of movement, speed, suddenness, excitement, and then, on the other, of an image that is complete, unfragmented, satisfying.

“Pat Steir Silent Secret Waterfalls: The Barnes Series” is at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia through November 17. Veronica Gonzalez Peña’s documentary about Pat Steir will be shown that the Barnes on May 13. An exhibition of new paintings by Pat Steir will open at Locks Gallery in Philadelphia on May 14.