Guy Tillim is a white South African born in 1962 who has devoted his career to documenting Sub-Saharan Africa. While nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century South African photographers were confined to the studio under colonial rule, the next generation—inspired by Drum magazine’s pioneering work in the 1950s—took up concerned photography and fought against Apartheid. Tillim is part of a third generation that pushes the boundaries of documentary photography and uses a range of media from photography to assemblage, installations, and video, all of which were recently featured in a large group show at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, “Africa Remix.”

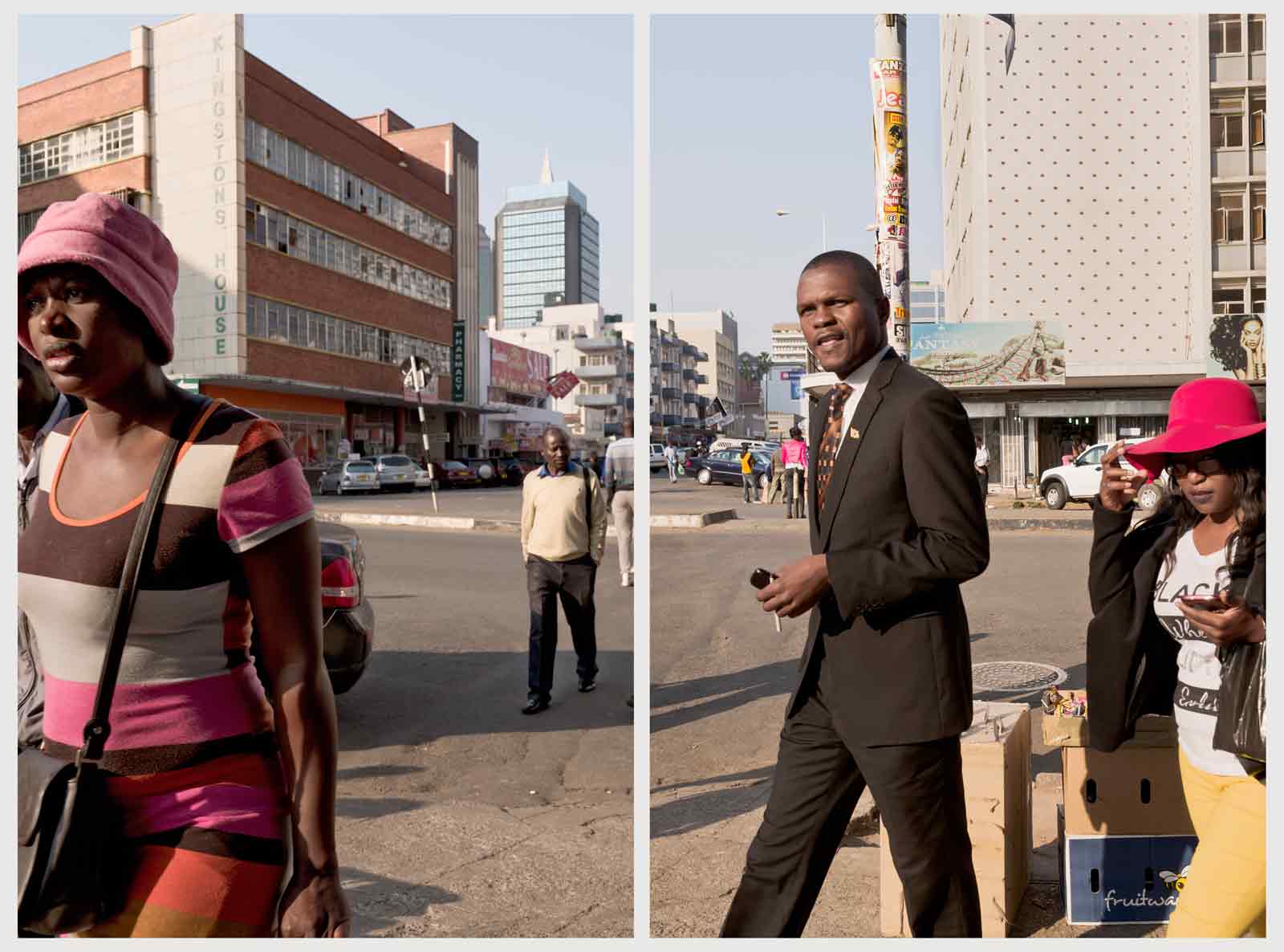

Over ten years ago, Tillim began to place his camera on a tripod at city street corners and would remain there for long periods of time, occasionally clicking the shutter. From a given corner, he photographed distinct moments, separate in time. He then displayed the images in groupings of two, three, or four—each photograph framed by a thin white line in order to preserve its individuality, but hung side by side as if together, they showed a panorama of the continuous street. By creating these diptychs, triptychs, and polyptychs, he wasn’t telling a story through a sequence, but trying, in his words, to “escape the tyranny of the single frame.” As if in reaction to Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment,” the photographer’s famous phrase for the significant fraction of a second in which a scene’s essence is captured, Tillim worked with a more diffuse sense of time and purpose. He has never believed that one frame can capture the essence of a situation. For Tillim, all moments could be decisive.

In 2017, Tillim used the proceeds from his Henri Cartier-Bresson Award to expand upon his project, capturing African cities where traces of historical periods—from colonialism to independence, socialism to global capitalism—coexist. Now exhibited in “Museum of the Revolution,” at the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Tillim’s work documents various African capitals where the signs of two revolutions can be seen in contemporary street life. In Durban, Maputo, Beira, Harare, Nairobi, Kampala, Addis Ababa, Luanda, Libreville, Accra, Abidjan, Dakar, and Dar es Salaam, the modernist buildings erected during the waves of independence in the 1960s sit alongside the elegant curves of colonial Art Deco structures built in the 1930s. In Johannesburg, the Brutalist architecture of a business center, initially conceived as a demonstration of white power but then abandoned in the early 1990s, stands in stark isolation. In several cities, streets and avenues named after Patrice Lumumba, the Congolese independence leader, remind passers-by of historical struggles for freedom. These sorts of scenes seem to create a theater set across which Tillim’s subjects move, like characters enacting a diurnal purpose.

Hawkers, street vendors, businessmen, housewives, shoppers, students—there is a sense of energy and a determination in the many bodies in motion. Some carry leather attaché-cases, others push a caddy or bear a heavy load, metal basins or plastic bowls balanced on their heads. Few pay any attention to the photographer or look at him directly. “The more visible you are to people in the streets, the more invisible, in a certain sense, you become,” Tillim told La Croix newspaper. “So standing in plain sight with my tripod-mounted camera, I became instantly seen, assimilated, and, ultimately, overlooked—which, as you know, is often a desirable state of being for a street photographer.” Something I noticed about these images was the absence of children, which is striking because they make up a large part of these cities’ populations. Perhaps in largely avoiding taking pictures of children, Tillim was reacting against the photojournalistic trope of the suffering African child.

Tillim started out as a photojournalist in 1986 after meeting David Goldblatt, a major figure known originally for his unflinching portrait of South Africa under Apartheid and more recently for his sweeping color landscapes. Tillim has said he thinks of him as a father. Goldblatt encouraged Tillim to look at people and events in South Africa without prejudice, not dismissing his political commitment to social change, but allowing his subjects to speak for themselves. In the late 1980s, Tillim joined Afrapix, a collective formed during Apartheid of both black and white South African photographers who believed that “struggle photography,” as they referred to their work, should be a weapon to combat and change a racist system.

Later in his career, Tillim collaborated with various press agencies, covering wars and conflicts in Angola, Afghanistan, Mozambique, and Rwanda. But as time went on, he felt that his work was growing repetitive: “I was always looking for the same images in any situation, with their diagonals, their vanishing lines,” he recently told the newspaper La Croix. “It was about isolating a human drama from its context.” Tillim felt that these images of suffering were offensive and clichéd, and that he was becoming desensitized to the violence and suffering he was capturing. This disillusionment echoes Susan Sontag’s reflection in On Photography that “the ante keeps getting raised… Images transfix. Images anesthetize.”

This is when Tillim became interested in documenting urban landscapes rather than conflicts, beginning with cityscapes, which he felt embodied a compressed sense of Africa’s geography and history. There is nothing sensational in these sequences of photographs. In spite of the crowds’ continual movement, the images convey a sense of peace and quiet meditation.

But as we take a closer look, subtle disparities and discrepancies of time and space appear between photographs, unsettling the viewer. The pieces of his puzzles don’t quite fit: Have we blinked? Between any two images, the appearance of the street has changed. The man in the red shirt who leaves the left-hand panel is replaced on the right by a similar man in a white shirt. A man’s torso becomes grafted to another man’s arm. The jogger never makes it to the other side of the street. Dry weather turns to rain, leaving puddles on the asphalt. There is a gap in time that the viewer’s imagination has to fill. There is no hierarchy among these images, so our gaze doesn’t concentrate on a dominant point but instead sweeps over scenes that convey the passage of time. It seems as if the photographer, suspending judgment, has given each element of the street equal play.

In the Cartier-Bresson tradition, the image was more about the photographer’s control of the frame, but in Tillim’s work it seems as though the subjects have been given a freer rein. Time neither seems to be racing forward, as in a film, nor does it feel suspended as in a single still image. Tillim’s photo-sequences are closer to reproducing memory with its rifts, loops, gaps, hiccups, and jolts. The images carry a sense of dynamism, yet uncertainty, an ambiguous feeling that maybe reflects a larger question about a continent’s future.

“Museum of the Revolution” is on view at the Henri Cartier-Bresson Fondation, Paris, through June 2. A catalogue of the same title is published by MACK and the Henri Cartier-Bresson Fondation.