The first image in “Viola Frey: Center Stage,” supersized on an atrium wall of the di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art in Napa, California, and printed on the cover of the exhibition pamphlet, is a photograph of the artist in 1996. She stands inside one of her just-larger-than-life ceramic female figures looking steadily at the camera—as if to demonstrate that her work is an extension of her person, but that the two are not the same. Her pose conveys the sense of scale, a mastery of her medium, and an easy relationship to both.

Frey’s sculptures and paintings are obliquely observational, bringing together popular vernacular objects, genres, and human forms to create three-dimensional works that signal familiarity—a man in a business suit—before turning toward mystification: Why is this figure cradling a female head? That feeling of the uncanny runs through many of the 120-plus artworks spanning 1963 to 2002 that appear in “Center Stage,” the artist’s first major museum survey on the West Coast since 1981.

A decade-and-a-half after her death, Viola Frey (1933–2004) remains a primarily Northern California presence. She was part of the 1960s and 1970s revolution in ceramic sculpture that gave us Ken Price’s slick biomorphic forms and Ron Nagle’s psychedelic fetish objects, as well as Robert Arneson’s representational meditations on masculinity. Like these artists, Frey helped to change notions that ceramics was inherently a medium for craft, not art. Whether because of her gender, the vast variety of her output, or both, acclaim comparable to her contemporaries’ has eluded Frey, despite frequent exhibitions of her work during and after her lifetime.

Frey grew up in a farmhouse flanked by livestock and a zinfandel vineyard in Lodi, a small town in the northern part of California’s Central Valley. Frey’s father, Reinhold, was an avid collector, gradually filling sheds with defunct farm implements, broken tractors, and electronics. By way of explaining her attraction to Surrealism and assemblage, Frey described the great pleasure that Reinhold took in watching nature reclaim what humans had tamed: machines could rust, crops could be supplanted by weeds. He once placed a broken-down truck out in a field just to watch a tree gradually grow through and around it. These themes of human efforts to transform and “denature” the environment, as nature rebels and reappropriates the human, would become an abiding preoccupation of her life’s work.

Frey left Lodi in 1953 to study painting at the California College of the Arts and Crafts, where she studied with Richard Diebenkorn. In 1955, she began graduate school at Tulane, where Mark Rothko taught as a visiting artist. Diebenkorn’s tightly structured but muscularly painted figures—figurative painting remained a place for experimentation and innovation in the Bay Area long after it was dismissed by East Coast artists and critics—and Rothko’s saturated color blocking was crucial to Frey’s development as she gravitated toward working in clay, a medium in which hue and form are inseparable.

After spending time in New York, where she worked in the accounting department of the Museum of Modern Art, Frey returned to the Bay Area in 1960, working in the Macy’s credit department and joining the faculty of the CCA in 1965. In those years, she began creating clay vessels and developed inventive homeware—goblets and cheekily named “California” plates in the shape of a cresting ocean wave. Photographs of the artist in her home, which she shared with her platonic life-partner, Charles Fiske, show an accumulation of twentieth-century figures, toys, and objects. This was not a collection of either oddball curiosities or recognizable icons, but rather the generic goods of twentieth-century dime stores. In Frey’s hands, dolls, cars, and tools could be cast and applied to a larger project—made her own. When she and Fiske moved to Oakland in 1975, she began populating her backyard with her figurative sculptures as if her creative fecundity were paying tribute to her father’s sensibility.

In the late 1960s, inspired by the mélange of materials at home in Lodi, as well as the table-top jumbles she saw on her frequent trips to flea markets, Frey developed a bricolage technique. She used custom and ready-made casts of forms from, or related to, her collection to create works that function both as singular, trophy-like objects and as complex figurative sculpture. Planet Full of People (Pink Nudes) (1969) imagines a flesh ball festooned with isolated, independent humanoids. In Junkyard Planet (1970), a goose stands atop a jug-form painted as a blue earth. An orange car, with a woman leaning out the front window, careens out of that aqua vessel.

Advertisement

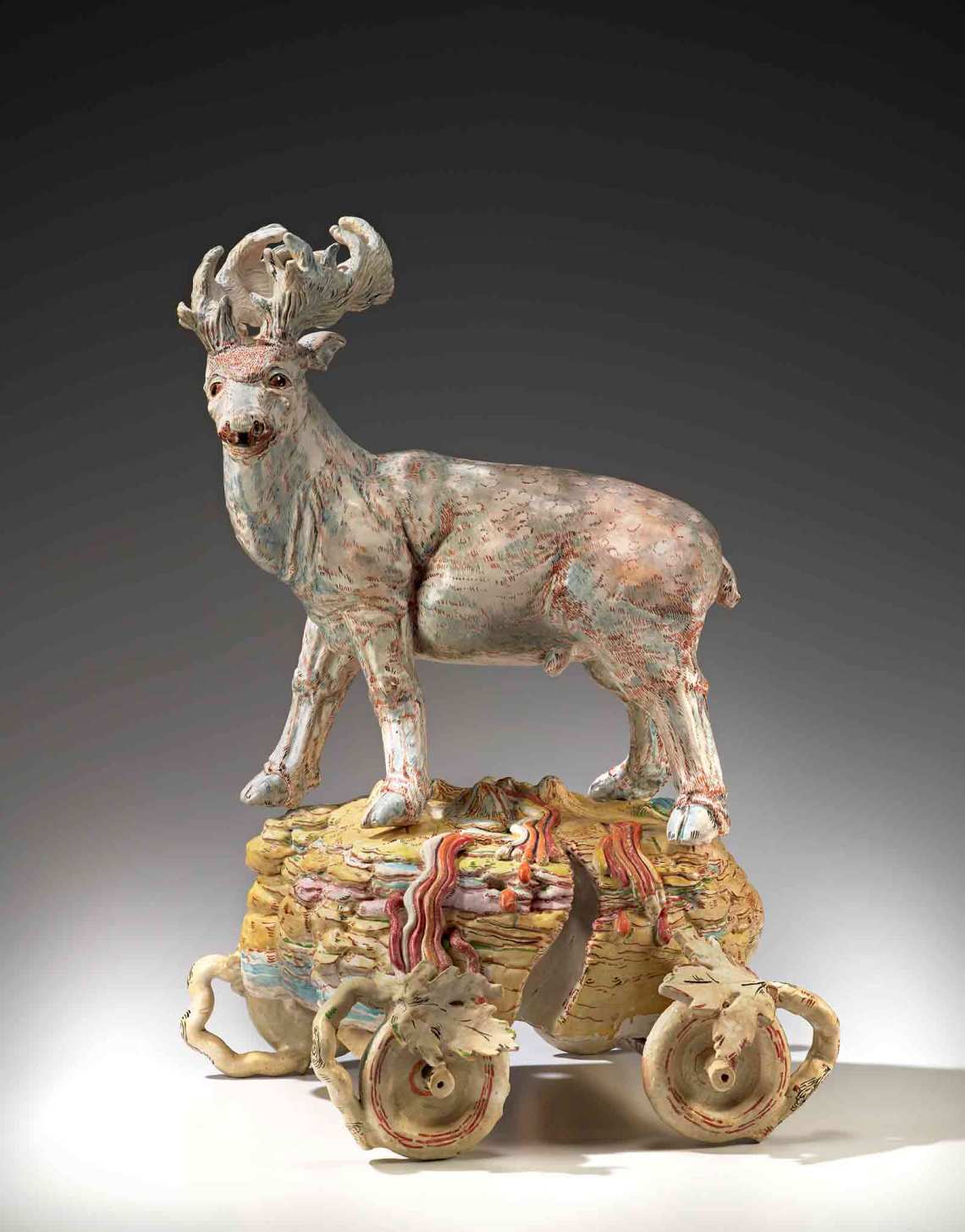

It is Frey’s take on the uniquely Californian mix of industry and nature, and, along with her planet series, the beginning of a concentration on environmental subjects that found focus in her mid-1970s series of animal sculptures. Deer, Endangered Animal Series (1972–1974) has a deer astride an earth that looks simultaneously like a stack of pancakes and layers of sediment, a bite-shaped chunk removed to indicate environmental distress. It sits on four toy wheels encircled by leaves, both made from generic casts. The assemblage evokes a fevered worry about the planet and a memory of an overgrown childhood landscape.

Some of the most notable works in “Center Stage” are carried forward from or related to a series of quickly painted ceramic plates Frey made depicting encounters between men in suits, skeletons, women, horses, and representations of the artist herself. In her paintings and drawings—both simplified figural scenarios and nearly photo-realistic tableaux, delicately rendered with infinitesimal detail—and ceramic sculptures, some of unusually large scale, men wear suits and women are nude or dressed in mid-century house-dresses. When nude, the figures, like the toy dolls from which they’re derived, do not have any visible genitalia; their limbs are jointed only at elbows, knees and shoulders, giving them a physical and emotional stiffness. They are differentiated primarily by posture and size. Men loom, as in Untitled (Man Standing on Glove) (1985), while women make either defensive or solicitous gestures, as in Untitled (Grandmother Series) (1978). They meet each other as intersecting but not interacting objects. In Frey’s late masterpiece, The Decline and Fall of Western Civilization (1992), men, women, and children stand shoulder to shoulder. The man, oversized and centered, holds a woman’s head in his hands. The figures seem unaware of one another, each seemingly in his or her own story.

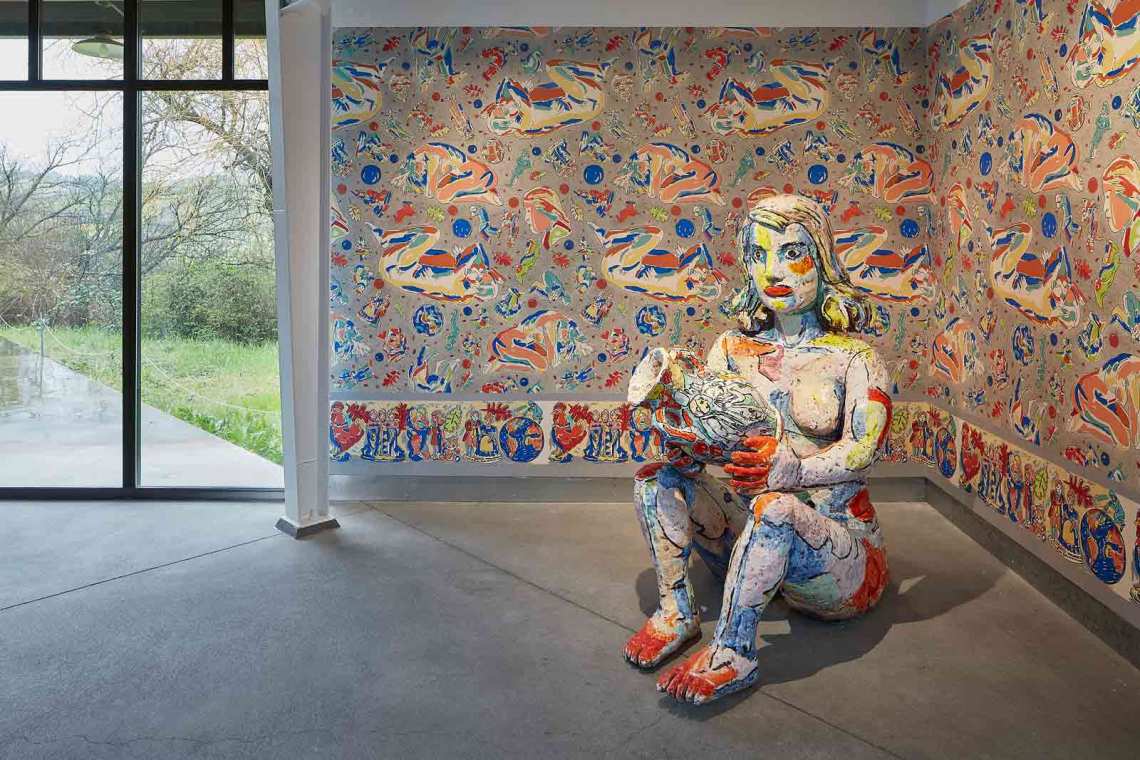

There are contemporary heirs to Frey in sculpture—women, mostly, whose physical and non-genre-specific approach to ceramics echoes Frey’s. I think of Ruby Neri, whose monumental vessels are festooned with robustly strong naked bodies; and, on the other end of the size scale, Kathy Butterly’s color-saturated hand-sized abstractions that evoke bodily bulges, crevices, and curves. As with Frey the making—the casts, the colors, the size—is inextricably informed by the material. Seated Figure with Vase (1998), the sculpture that both opens and closes the exhibition loop, is a slightly larger-than-life female nude, grasping a vase painted with the male/female figures Frey had by then been delineating for decades. Blues, reds, and yellows are roughly brushed on as if with a roller. It’s difficult not to wonder if Frey is offering us a glimpse at her own process: the woman’s expression is stern. Is she beholding existence, creating a world, or contemplating its destruction?

“Viola Frey: Center Stage” is on view at the di Rosa Center for Contemporary Art in Napa, California, through December 29.