There’s an eerie moment, as you emerge from the rue Saint-Merri, with its bars and pavement cafés and look down into the square before the Centre Pompidou. Below, a man is blowing bubbles, swept into the air high above him, where a huge dark goddess rises on a banner against the exoskeleton of the Pompidou, with its steel grids and tubular escalators. Facing away, the robed figure raises her arms, as if to open the heavy curtain behind her, but her head is totally obscured by a shining star. Beside her, the name shouts DORA MAAR.

This haunting show, in the cool gallery spaces high above the city that Maar knew so well, makes it clear that she was indeed a star, a leading figure in Surrealist photo-montage of the mid-1930s. Maar’s largest exhibition in France, it contains over 400 of her works, yet, like the model in the banner, she turns away, and hides her face, remaining enigmatic in her work. In Self-Portrait with Fan (1930), she shows only her reflection in a mirror, her serious gaze shrouded by the circles of an electric fan. She looks as if she might blow away, dissolve into fragments.

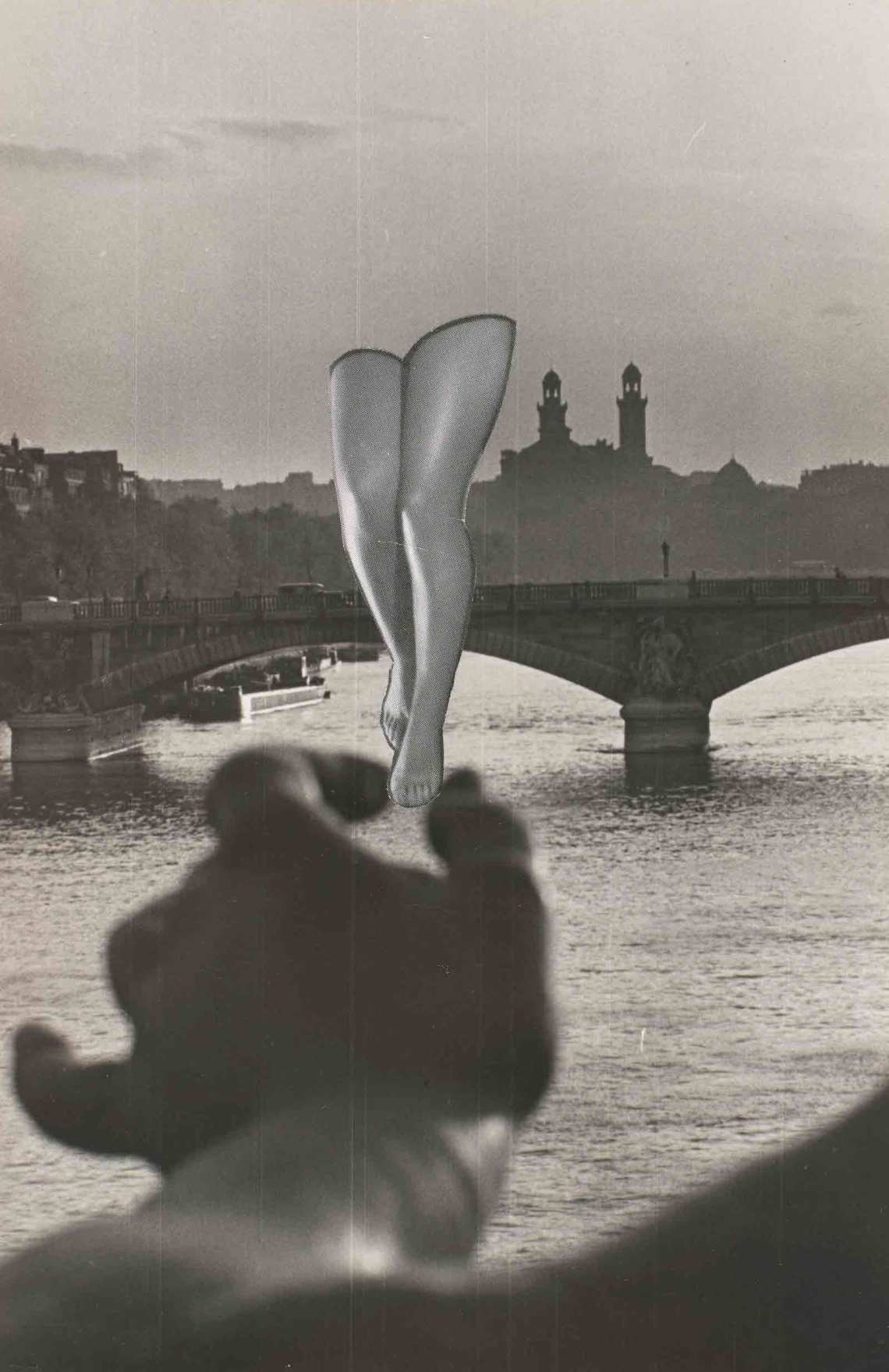

Her Surrealist montages deepen this impression. The images are powerful, haunting, stylish: a hand with a painted thumbnail curls out of a shell, like a hermit crab crawling on a blank field of sand against a lowering sky. In Les Yeux (circa 1935) eyeballs seem to float on a sea of tears. In Jambes (circa 1936), a long twist of hair spirals down from the apex of a triangle formed by two disembodied legs.

Henriette Théodora Markovitch was born in Paris in 1907. Her French mother ran a fashion boutique but she spent much of her childhood and youth in Argentina, where her Croatian father worked as an architect. Returning to France when she was nineteen, Maar studied art with fellow student Henri Cartier-Bresson until Marcel Zahar, an older art critic and mentor, urged her to turn to photography. Already, she was on the fringes of Surrealism: her close friend Jacqueline Lamba would later marry André Breton. Changing her name to Dora Maar, she began publishing her photographs in magazines, and in 1932 opened a studio with the film-set designer Pierre Kéfer.

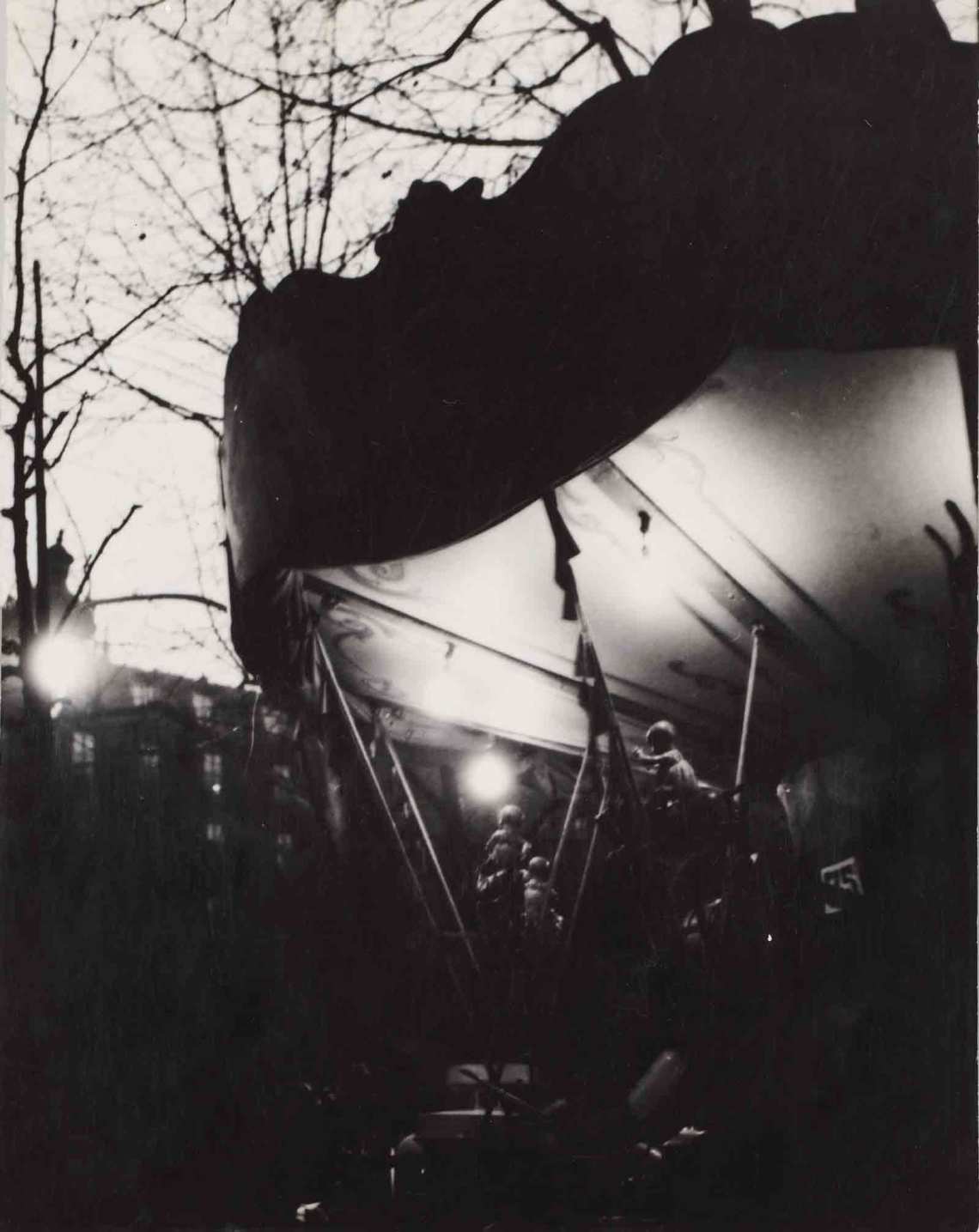

Maar quickly established herself as a witty, off-beat fashion photographer, setting up on her own in 1936, at 29 rue d’Astorg. The dazzling opening rooms at the Centre Pompidou show that she could capture anything, from sculpted satin ball gowns to cheery adverts for the sun-tan cream Ambre Solaire. But even in this commercial milieu she veered toward the abstract and the odd. In a swimsuit advertisement, Maar superimposed the bather at an odd angle against a pulsing, dappled background that recalls a Hockney pool. For Dolfar, a maker of curling tongs, she gave her models heavy ringletted heads, like brooding archaic statues. For an anti-aging cream, she veiled a dreaming portrait of her beautiful friend, Nusch Éluard, wife of the poet Paul Éluard, behind a huge spider’s web. Even her erotic, sensuous images often had a darker side, like the perfect figure of Assia (1934), lit so that she is almost dwarfed by the black, deformed shadow looming behind her, recalling the menacing, dreamlike world of shadows in German Expressionist photography and film.

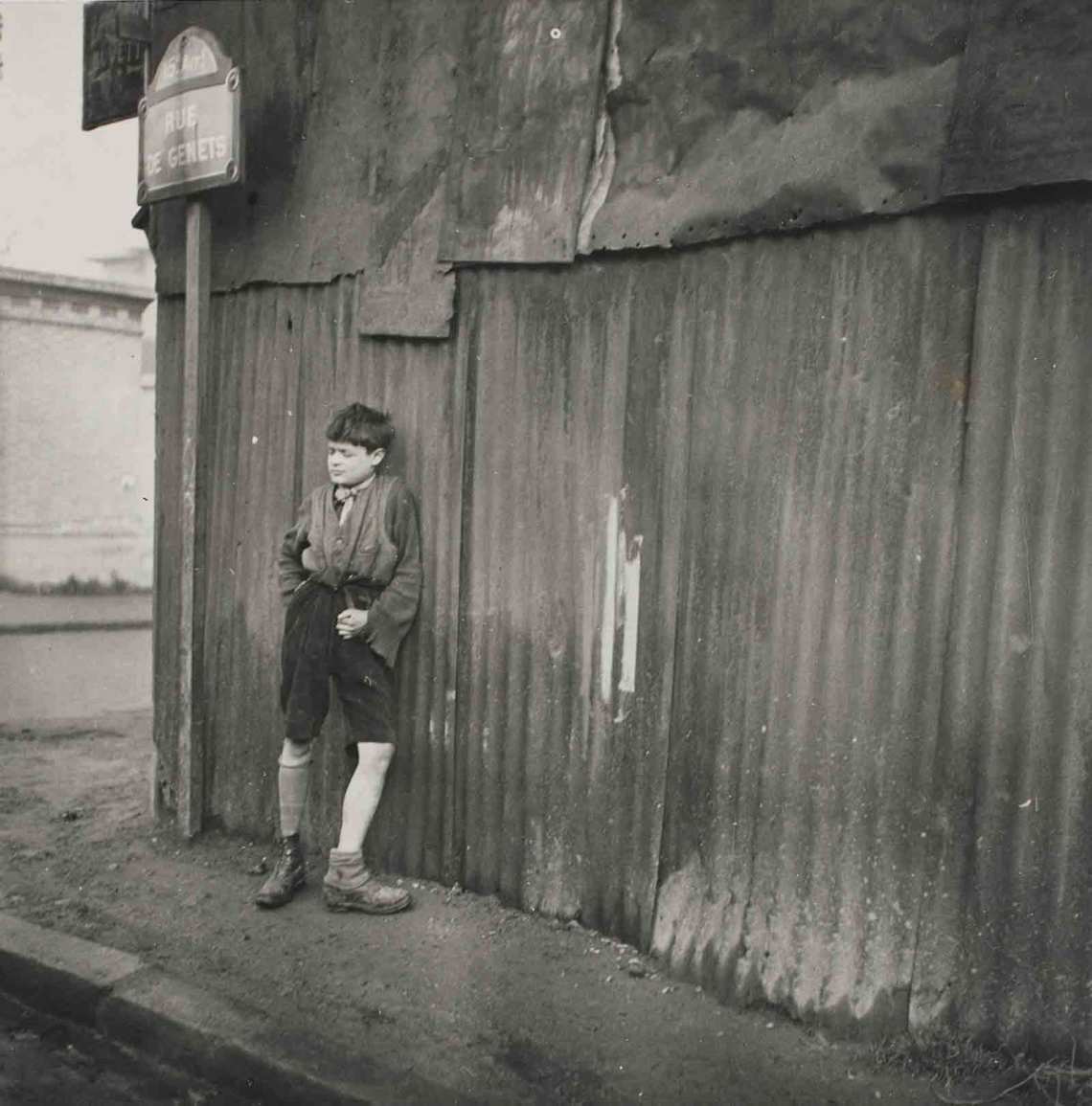

Outside the studio, Maar’s inventive, piercing gaze acquired a political dimension as she began to photograph people of the streets. In Rue de Genets (1933), a boy with one sock weirdly rolled down leans painfully against a corrugated shed. In Barcelona that same year, she pounced on odd images of beggars, children, musicians, old men asleep on benches, young men waiting for work. In London the following year, when the Depression was biting, she photographed a legless veteran displaying a model warship to attract the generosity of passers-by, and a squinting old woman crouched outside the Midland Bank. The streets offered their own surreal moments: a wicker kangaroo on the pavement, a dog perched above a gateway, a man with his head down a manhole.

Many of these photographs were shown at the “Documents of Social Life” exhibition put on in Paris by the Communist-aligned Association of Revolutionary Artists and Writers in June 1935. Maar joined the October Group, a radical collective of artists and writers, and the ultra-left organization Masses, in which she met Georges Bataille. In February 1934, in response to Fascist demonstrations in Paris, she signed the manifesto Appel à la lutte, which called for all left-wing organizations to fight against the threat from the extreme right. A year later, she joined Contre-Attaque, a carnivalesque, revolutionary group founded by Bataille and Breton, opposing the government, Fascism, and capitalism, but also the pro-Moscow French Communist Party.

Advertisement

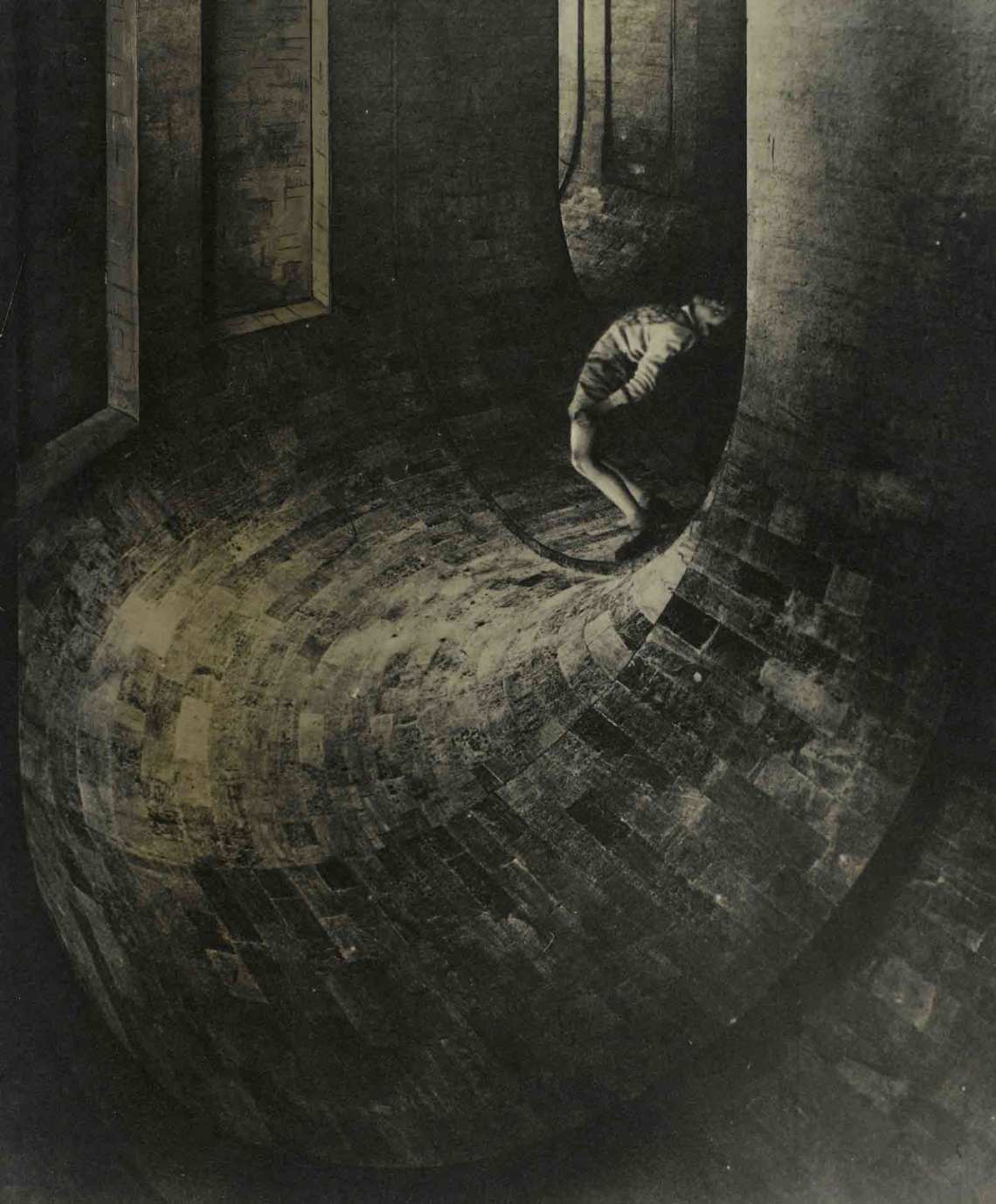

By 1933, Maar was also an accepted figure on the Surrealist scene, one of the few women to exhibit with the group. (Her set also included Man Ray and Brassaï, both of whom photographed her.) The main room at the Centre Pompidou glimmers with her Surrealist works, suggesting her fascination with dreams and the unconscious. The human body and the social realm are rearranged and the natural world flowers with a buried energy, as in her picture of coral rising from the sea, the life below erupting through the surface. Maar re-envisages her own life, too, even her own studio—in the tinted 29, rue d’Astorg (1935), a heavy, pin-head figure perches on a tilted stool beneath off-balance arches. Accompanying studies show that she created this primitive queen in her vertiginous setting by placing a photograph of a headless figurine against an early-twentieth-century print of the Orangeries at Versailles; she made the warped arches by bending the cardboard on which that photograph was printed. The arches reappear, upside down, like shells, or tunnels, or the huge stone lips of an underground monster in Silence (1935–1936), and in Le Simulateur (“The Simulator”) (1936), in which a boy arches backward as if shot. How clever she is, how unsettling her exploration of the depths of our psyches.

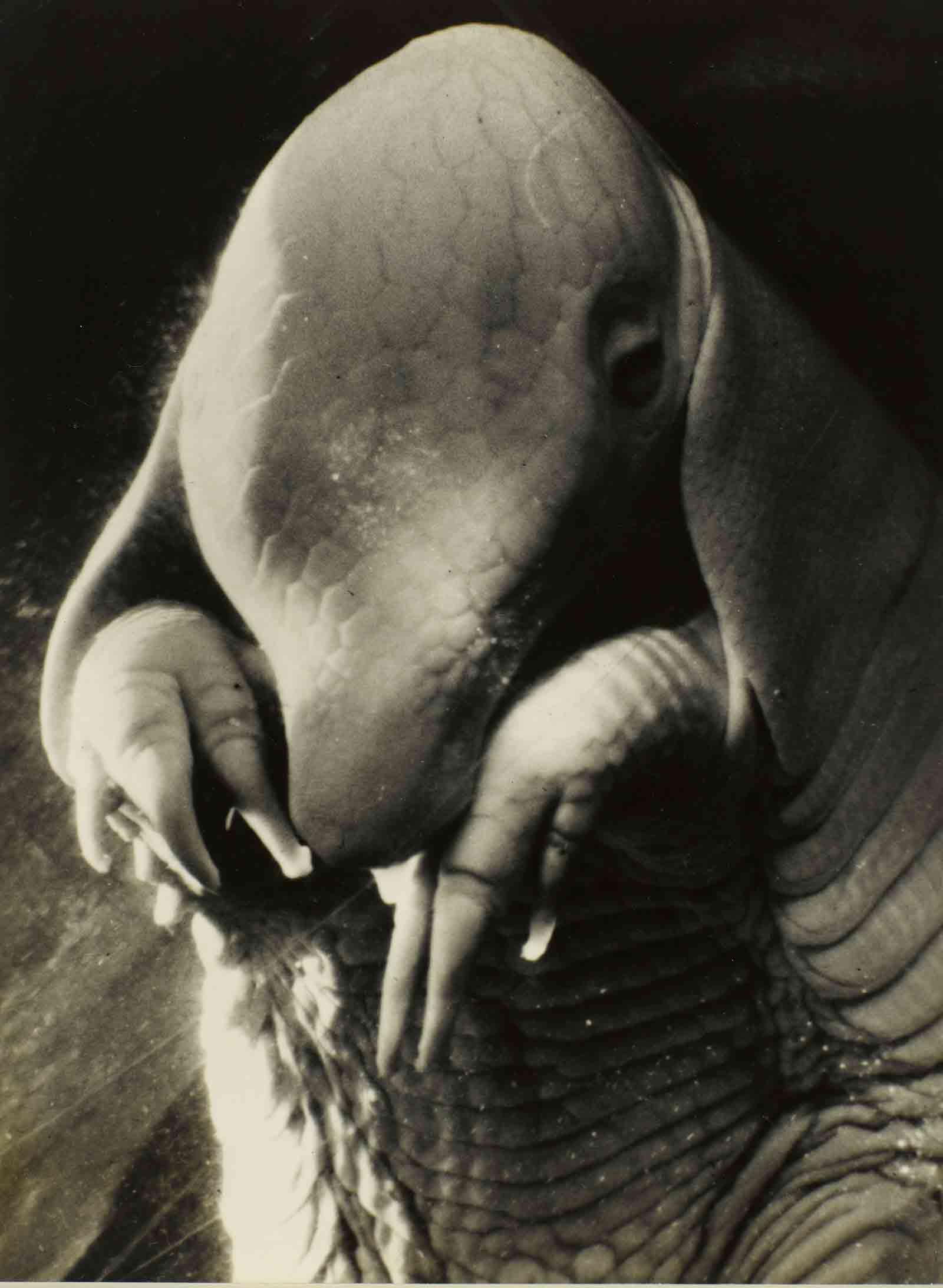

The Simulator was one of three works shown at the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936. Another work, stranger still, was her Portrait of Ubu. The title derives from Alfred Jarry’s proto-Surrealist play of 1896, Ubu Roi, an absurdist parody of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, about power, corruption, and violence. But the scaly being shown here, with its dented, soft-nosed face and beseeching claws, seems to come from another world. Maar always refused to say what it was, but in the catalog, the critic Jean-François Cornu explains that the little creature is now generally agreed to be an armadillo fetus. The Surrealists often portrayed animals using an ironic anthropomorphism to suggest the underside of human consciousness. Maar plays with this notion of the primitive, hinting at Ubu Roi’s laziness and vulgarity through the armadillo’s bulbous nose. But instead of showing the malevolence of Jarry’s king, she substitutes a disturbing, reptilian immobility. The little creature’s expression is sad beyond tears.

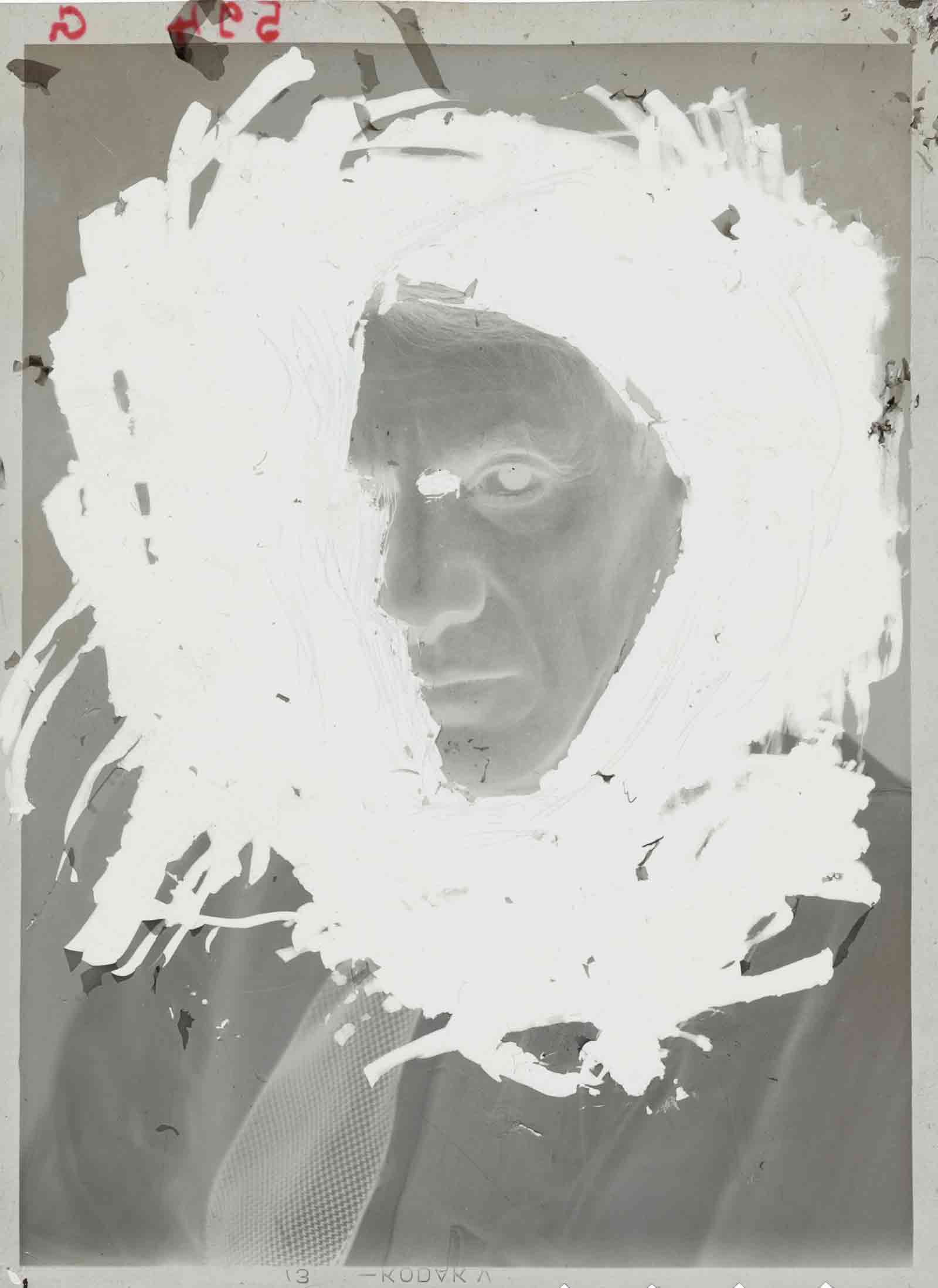

By the time of the International Exhibition, Maar’s life had taken an unexpected turn. In late 1935, she had been working as a stills photographer on the set of Jean Renoir’s film Le Crime de Monsieur Lange, and at the press screening in January 1936, Paul Éluard introduced her to Pablo Picasso. Maar was twenty-eight and Picasso was fifty-four; his marriage to Olga Khokhlova had collapsed, and he was living with the young Marie-Thérèse Walter, who had recently borne his daughter Maya. Picasso later said that this was the most difficult time in his life. Maar revived him, bringing new inspiration: he was fascinated by her love of extremes, her aura of danger, her wit, her elusiveness. She photographed him in her studio and soon they were lovers.

Along with Éluard, Maar encouraged Picasso to take a stand against Fascism in the Spanish Civil War, and was intimately involved when he began to work on his response to the German bombing of the Basque town of Guernica on April 26, 1937. From May to June that year, Maar recorded every stage of his painting Guernica for the magazine Cahiers d’art, and as the studio light was poor, she touched up the negatives to show every subtle change and nuance. This careful documentation, an invaluable source for art historians, was itself a kind of Surrealist project—recording the gradual morphing and metamorphosis of a painting.

Maar and Picasso were together for eight years, and under his influence Maar began to paint as well as use her camera: several portraits and still lives she made in these years are on show at the Pompidou. At the start of their relationship, Picasso painted her as a bird, a water nymph, a flower, but as time went on, he showed her caught in a mesh, and depicted her again and again as the grief-wracked figure of The Weeping Woman (1937). The designation—which she always hated—was prophetic. Their relationship was marred by physical and mental abuse, with Marie-Thérèse always in the background. As Françoise Gilot described in her memoir, at one point he encouraged the two women to wrestle while he watched; at another he beat Maar into unconsciousness. After 1943, when Picasso met Gilot, their relationship stuttered on for three years, but Maar collapsed with a nervous breakdown, receiving electric shock treatment—banned at the time—and then beginning two years of analysis with Éluard’s friend Jacques Lacan.

Advertisement

In 1946, when they finally separated for good, Maar retreated. For years, she gave up photography. Instead, she turned to religion and poetry, and in the house that Picasso had bought her in 1945 at Ménerbes in Provence, she painted portraits and small, eloquent, near-abstract landscapes of the light on the Luberon hills and the wide valley below. In her old age, in the 1980s, she went back to her darkroom, mixing paint and photography, playing with negative images, and creating photograms, images made without a camera. A star in eclipse, Maar died in 1997, experimental and surreal to the last.

“Dora Maar” is at the Centre Pompidou through July 29. It will travel to the Tate Modern, London, from November 20 through March 15, then to the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, in April 2020.