On February 10, 2002, in a New York State prison cell, the bestselling author and twice-convicted killer Jack Abbott hanged himself with an improvised noose. That same day, the body of the man I murdered washed ashore on a Brooklyn beach in a nylon laundry bag. My reason for connecting these two events is to try to account for my crime, to understand better why I did it, and to describe what Abbott’s legacy, as a prison writer of an earlier generation, has meant for me as a prison writer in this generation.

Jack Abbott was one of America’s best-known prison writers of the twentieth century, though it can be hard to tell how much this was due to the merits of his work, to the high profile of some of his supporters, who included Susan Sarandon, Christopher Walken, and Norman Mailer, or to the public’s fascination with his propensity for violence. Writing gave Abbott a second chance in life, and in 1981, after serving eighteen years, he was released on parole. Shortly thereafter, he killed again. He never came back from that. His supporters, and even his will to write, deserted him. He died, much as he had lived, alone and angry.

When I started my stretch behind bars in 2002, I had never heard of Abbott. After I read his work, I came to identify with parts of his conflicted character, and I have at times taken inspiration from his writing. But I also resented how Abbott’s actions after he was paroled cemented a mistrust of prison writers and prison writing programs at a time when public opinion was swinging away from the prevailing liberal consensus in favor of rehabilitation.

Jack Henry Abbott was born in Michigan on January 21, 1944, to an Irish-American military man, who was a drunk, and a pretty Chinese-American woman who used to work as a prostitute around the base. After the war, his father abandoned him and his older half-sister—and that was the beginning of what made Abbott, in his words, a “state-raised convict.” By four, he and his sister were in foster care; at twelve, he landed in Utah’s State Industrial School for Boys. By nineteen, he was in the State Penitentiary for robbing a shoe store and making out stolen checks to himself.

In 1966, two years into his five-year stint, Abbott stabbed two prisoners, killing one, James L. Christensen, and wounding another. Abbott told Mailer that Christensen was trying to make him his “prison wife”; another version was that Christensen told the guards Abbott had contraband in his cell. There was one other explanation Abbott gave, perhaps the truest, when he wrote: “Here in prison the most respected and honored men among us are those who have killed other men, particularly other prisoners. It is not merely fear but respect.”

Abbott received a concurrent three-to-twenty-year sentence for the prison killing. Then, in 1971, he escaped, robbed a bank in Denver, and was captured and back in prison a month later. In and out of solitary in different federal prisons across America, Abbott read Marx and Engels, Sartre, Lenin, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche. His first foray into letters came when he struck up a penpal relationship with Jerzy Kosinski, then president of PEN’s American Center, though this fizzled out when Abbott called Kosinski a turncoat for abandoning the Communist cause. Then, in 1978, Abbott wrote to Norman Mailer, offering to provide the famous author insight for a book he was writing about Gary Gilmore, with whom Abbott claimed to have served time.

“If you went into any prison that held Gilmore and me,” Abbott wrote Mailer, “and asked for all the prisoners with certain backgrounds… you would get a set of files, a list of names, and my file and name will always be handed you along with Gilmore’s.” Like Abbott, Gilmore had spent most of his adolescence and adult life in prison, where he, too, read widely and was a talented painter and letter writer. He was paroled in April 1976, at the age of thirty-six. Four months later, in short succession, Gilmore shot and killed two people in Utah.

His case became a cause célèbre after he refused to appeal against his death sentence. In 1977, facing a firing squad, Gilmore said, “Let’s do it.” They shot him to death. In the spring of 1980, Norman Mailer’s novelized true crime account of Gary Gilmore’s story, The Executioner’s Song, won a Pulitzer Prize. “Your letters have lit up corners of the book for me,” Mailer wrote Jack Abbott in prison, “that I might otherwise not have comprehended or seen only in the gloom of my instinct unfortified by experience.”

Advertisement

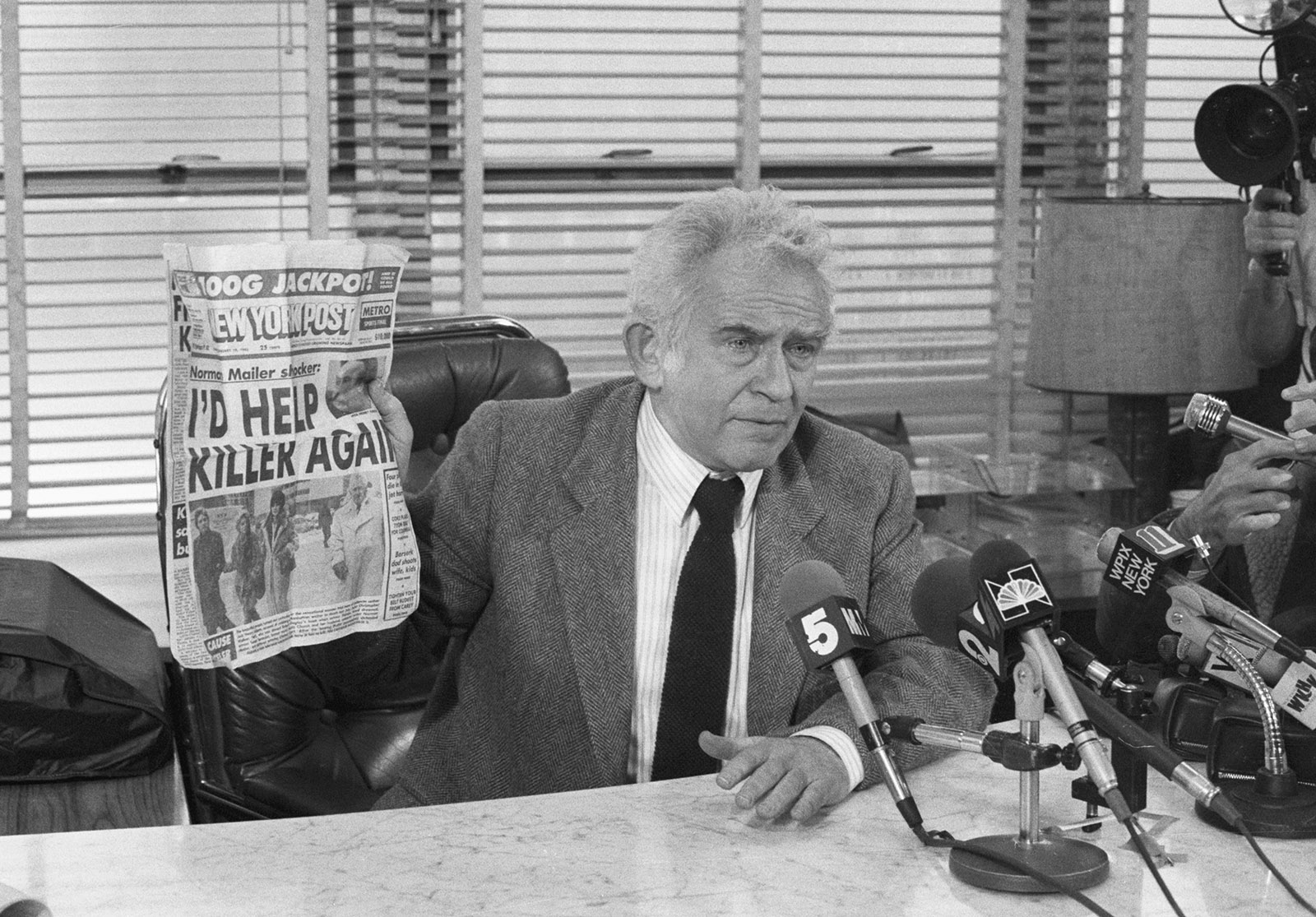

Not long afterward, Mailer introduced Abbott’s words to the world in The New York Review of Books, providing an introduction for excerpts from more than twenty of Abbott’s letters. “I found the content remarkable, and a great help to comprehending Gilmore,” wrote Mailer, “but, apart from that, Abbott’s own writing impressed me as being as good as any convict’s prose I had read since Eldridge Cleaver.” No doubt, Abbott’s accounts of prison violence got Mailer’s initial attention, but even in those first published fragments, it was also his capacity for introspective reflection and an autodidact’s existentialism:

You try only to keep yourself together because others, other prisoners are with you. You don’t comfort one another; you humor one another. You can’t stand the sight of each other and yet you are doomed to stand and face one another every moment of every day for years without end… And the manifestation of the slightest flaw is world-shattering in its enormity… Because there is something helpless and weak and innocent—something like an infant—deep inside us all that really suffers in ways we would never permit an insect to suffer.

An editor at Random House read the article, which led to Abbott’s own book deal for In the Belly of the Beast: Letters from Prison, published the following year. In the meantime, Abbott was also taken up by Review editor Bob Silvers, who assigned him a book of interviews with a dozen death-row inmates. In Abbott’s review, which appeared in a March 1981 issue, he wrote about how he’d spent time on death row after killing Christensen (though he was not in the end charged with a capital crime). His meditation on the predicament of convicted killers would acquire a sad retrospective irony:

I know of no man who has walked away from death row, and life imprisonment, and then been convicted of crime again, much less of murder. When you are defending your life with arguments and pleas you are engaged in a special struggle not given to many in any society. You come away from it more reserved, more considerate: you learn how precious, how fragile, life in society can be.

Life in society did prove precious and fragile. Mailer, Silvers, and Abbott’s editor at Random House all wrote letters of support that were presented at Abbott’s parole hearing in Utah. He was released from prison in June 1981, just as In the Belly of the Beast was published. Mailer had again contributed an introduction, even more effusive in its praise. It concluded:

There is never, when we speak of possible greatness in young writers, more than one chance in a hundred that we are right, but this one chance in Abbott is so vivid that it reaffirms the very idea of literature itself as a human expression that will survive all obstacles. I love Jack Abbott for surviving and for having learned to write as well as he did.

Then thirty-seven years old, Abbott had spent more than half his life incarcerated, and he struggled with what he called the “arrested adolescence” of his prison life. Abbott made it out “from max. security—after three years of solitary,” he later reflected, “straight away into that artificial monster called Manhattan.”

He settled in a Lower East Side halfway house and started a job as a researcher. He appeared on Good Morning America with Mailer, did an interview with Rolling Stone, learned to admire Rembrandts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and dined with writers. At a party for In the Belly of the Beast, Abbott was withdrawn, Silvers recalled: shy and taciturn, he stood with his back to the wall, talking only to people he already knew. I can imagine Abbott in those moments, craving something to take the edge off his anxiety, like the drugs he took in prison.

“His prose is most penetrating, most knife-like, when anger is its occasion,” Terrence Des Pres wrote in his New York Times review. “How, I wonder, shall this talent serve Abbott now that he is free?”

After six weeks of freedom—and a day before the Times review appeared—Abbott, likely buzzed after an evening of partying, got into a fight outside a diner with a twenty-two-year-old night manager named Richard Adan, stabbing and killing him. If Gilmore, with his senseless murders, brought back executions in America, it was Abbott who, as Jerome Loving argues in his 2017 book Jack and Norman, “helped bring back the public wrath against prisoners.”

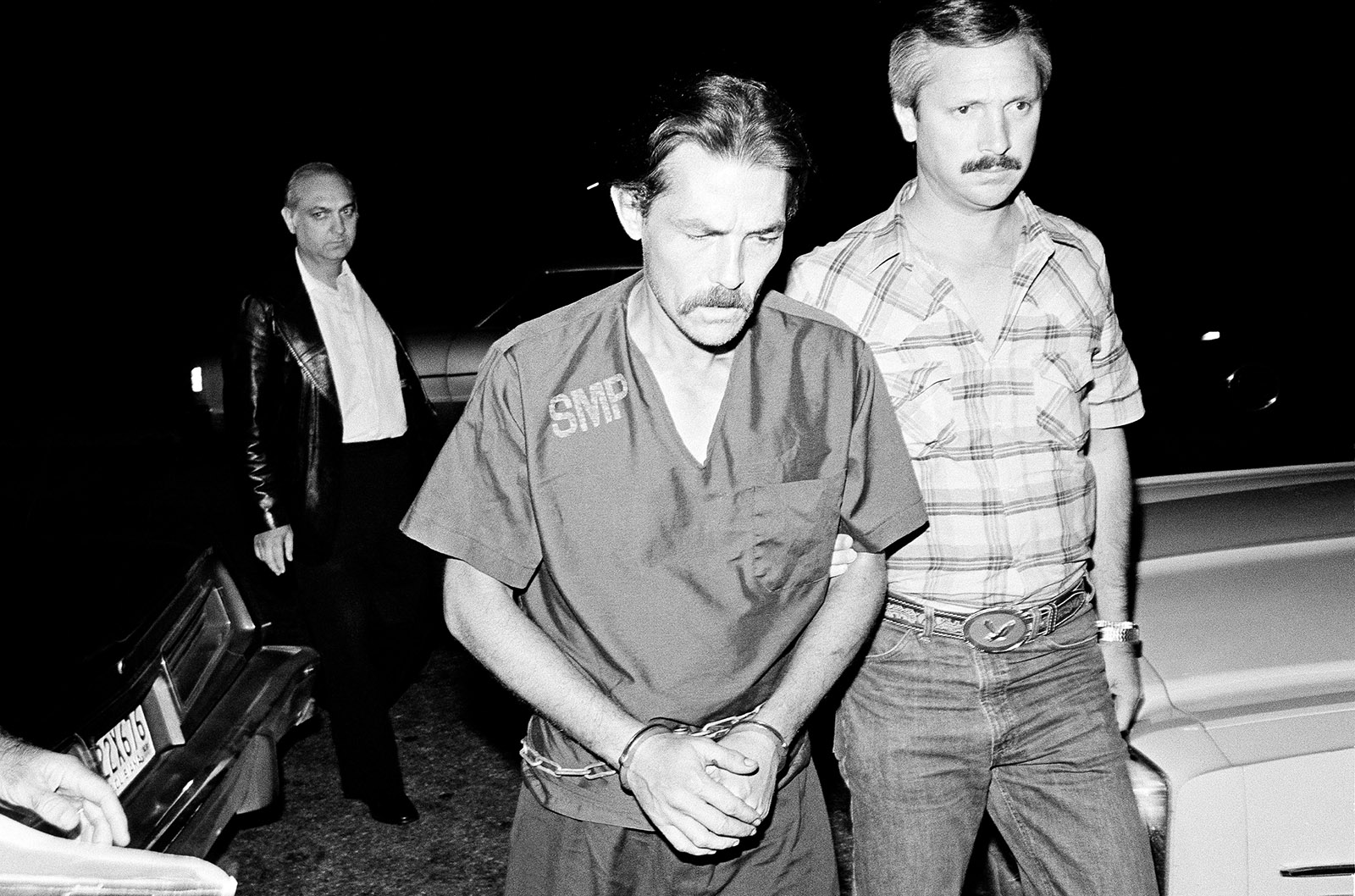

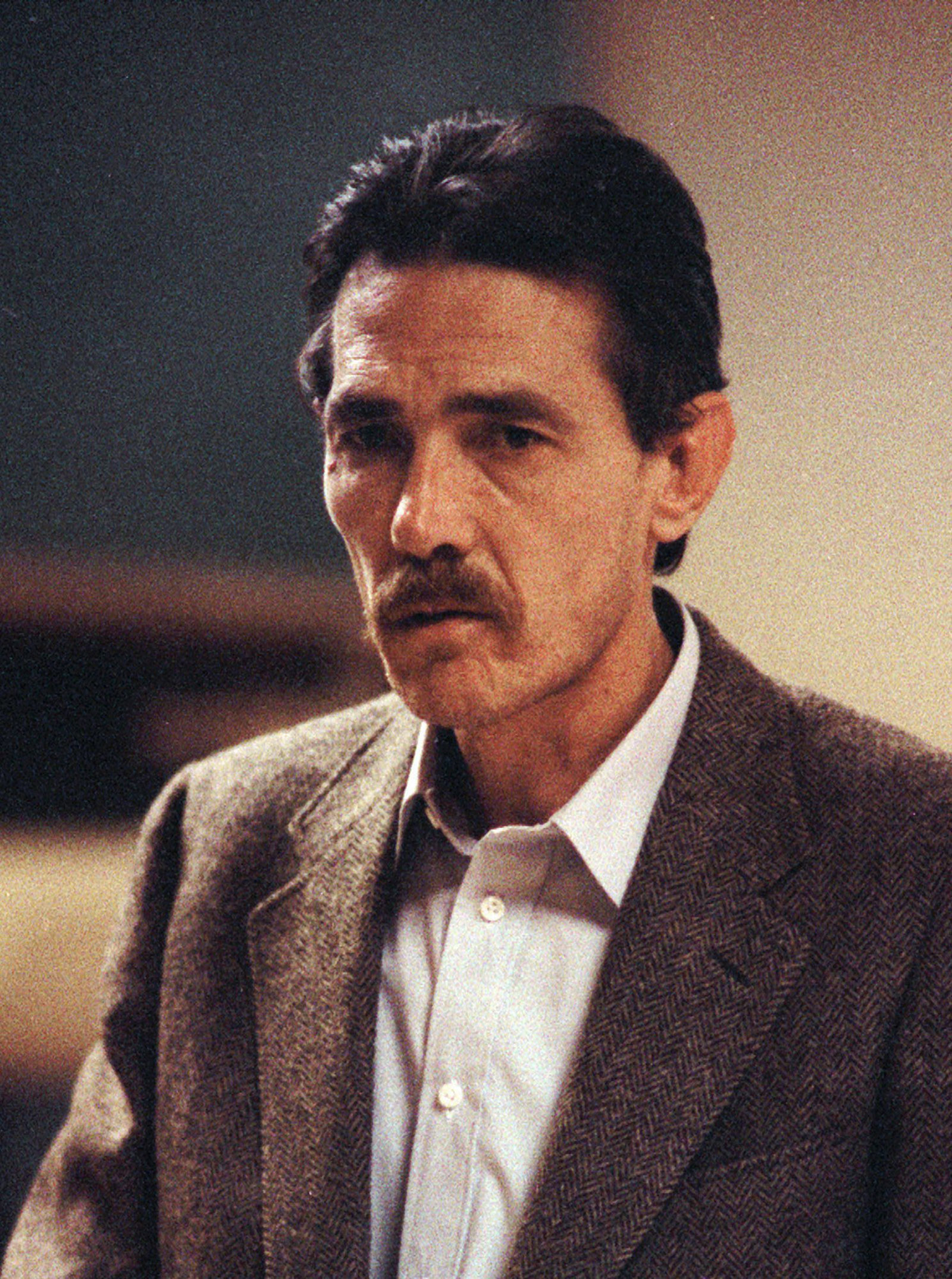

After Abbott killed Adan, he went on the run. A detective tracked him down in Louisiana, where he was trying to get work on an oil rig. Mailer attended Abbott’s trial, along with Walken and Sarandon (who named one of her sons Jack Henry). Abbott was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to fifteen years to life. Since he had violated parole, he also had to finish the time owed on his federal sentence.

Advertisement

Abbott’s supporters were excoriated by the press. Yet Silvers still sent books to Abbott and corresponded with him in prison. Mailer stood by him, too. “Whether Jack is the original seed of evil,” Mailer told Ed Bradley on 60 Minutes, which aired on April 18, 1982, a few months after Abbott was convicted, “whether Jack is a victim of his environment—and that’s a question that’s too deep for me to answer—that there is no question that whatever Jack is, he was made much, much worse by all those years in prison.”

*

I was born in New York on April 26, 1977. My father, like Abbott’s, was an Irishman who had served in the military; he worked as a bartender in Manhattan, and he, too, was a drunk. Mom didn’t necessarily like being a mother, after having three children with her first husband; that man had custody and raised their kids out on Long Island. After I was born, my parents fought a lot, and I was placed in a foundling home for some time. When I was one year old, my father left. My mom learned to navigate the housing system, filling out applications and waiting in lines. Eventually, we moved to a project in Sheepshead Bay, southern Brooklyn.

Mom obtained vending permits, bought hot dog wagons, and hustled the avenue where fishing boats docked to entice the hungry anglers. Soon, she snagged one. George, another Irishman, was a longshoreman and captained a fishing boat on weekends. He would wake me up to go fishing by tossing a wet rag on my chest. Mom’s weed wafted around the apartment, and hot dogs packed the freezer. Under the carpet by the side of her waterbed, I’d swipe singles from a stack of cash and buy grape Now & Laters. Seeing my purple tongue, Mom would ask where I got money for candy. I’d lie, and she’d beat me good.

When I reached fifth grade, Mom sent me to the Malcolm Gordon School for Boys, a boarding school housed in a converted nineteenth-century mansion, overlooking the Hudson River across from West Point. About twenty-five of us lived there. Mom convinced the headmaster, a man with a big mustache and firm handshake, to give her financial aid. The headmaster’s hunchbacked mother used to walk the dining room from table to table and run the ring on one of her fingers hard down our spines: sit up straight, elbows off the table.

During summers, Mom sent me to a Jewish summer camp, receiving financial aid for it by changing her name to Feinstein. “John is argumentative and aggressive,” a 1986 camper evaluation reads. “John has emotional and learning problems, causing fights and counselor frustration.”

From summer camp, it was back to boarding school. I was always away. I’m still away. Looking back, reading those reports from my cell in Sing Sing, another neo-Gothic structure overlooking the Hudson River, I can say that my aggression has subsided. I haven’t had a fight in prison in over ten years. Today, I bristle at the constant din and aggression. I’m subdued, in my head, thinking, writing.

In seventh grade, during school break, news came that my father, at forty-nine, had died of a heart attack. I later learned that he had committed suicide, using a shotgun. Around that time, Mom and I moved to George’s rent-stabilized railroad apartment in Hell’s Kitchen, near the theater district on Manhattan’s West Side. George liked to tell stories about the Westies, the murderous Irish mob that had reigned there when he was growing up. By the mid-Eighties, most of them had gone away to federal prison for life.

On a cold night, the twelve-year-old me would be lying in the backseat of George’s car, half-asleep, cruising upstate to his hunting cabin, listening to him at the wheel telling Mom how some gangster would walk into a bar and shoot a man in the head as if it were nothing. Years later, keeping a journal in prison, I realized how much those stories had made an impression on me. My father had just killed himself. They were not talking about him. They were talking about this killer, though. He mattered.

When I was thirteen years old, I was expelled from another boarding school after attacking an exchange student with a knife. Mom enrolled me in a public high school in Manhattan. I never went. Instead, I ran around the city, rode the subways, and smoked weed with my friends. Mom took me to a therapist; I had ADHD and Mom told me I had the alcoholic gene like my dad. She dragged me to AA meetings and put me on antidepressants.

So that I could work in the Broadway theaters as an usher with the other neighborhood kids, George took me to a guy who gave me forged ID papers that said I was older. Soon, I stopped going home and started hanging out with hoodlums on the corners. I started selling dime bags of weed. In 1992, after a brawl involving friends outside a bar called Irish Eyes, our hangout, I was picked out, arrested for assault, and sent to Spofford, a juvenile jail in the Bronx. I was fourteen. The family court judge who sentenced me to eighteen months told me I’d be back if I didn’t get my act together. She was right.

At seventeen, back in Hell’s Kitchen, I was arrested for possession of a firearm. I was holding a pistol for a friend when detectives jumped out of a yellow cab, found the gun, and booked me. The judge sentenced me to one year on Rikers Island. There, I was a white, I was the minority. On my first day there, in a large holding cell, I got jumped, had the sneakers ripped off my feet, and my face smashed against the bars. The side of my eye split and I bled a lot.

I soon learned that there was no reasoning with those kids; they were vicious and impulsive and violent, and that’s exactly how I had to be. The more I showed that I was willing to go there with anyone, at any time, the more peace I had. That was the sick paradox of it.

At Rikers, I would see Alex, a kid I grew up with in the Brooklyn projects. Of black Panamanian descent, fluent in English and Spanish, Alex was on another unit, awaiting trial on a drug-related murder charge. But there were no eyewitnesses, and in 1996 a jury acquitted him. It was three years before I next saw Alex, on the outside. We were both stopped at a red light in Brooklyn, each in a flashy car. A small guy with a big reputation on the street, Alex sold PCP, or angel dust, in liquid form soaked into Newports for smoking. I sold heroin and cocaine. We thought we were living the high life. It soon caught up with us.

A couple of years later, I learned that Alex had started shaking down one of my top sellers. The Russian kept coming up short; eventually he told me why. I had to act.

“It is hard to bring yourself to these acts,” Abbott writes in a typical passage from In the Belly of the Beast about the psychology of violence, “but you take a deep breath, look intelligently at what you must do, and you do it even though you are scared stiff and sick to your stomach.”

On a cold December night in 2001, I took Alex for a ride in a rental car, bringing along a cocked and loaded AR-15 in the trunk. Alex seemed leery, so to offset his suspicion, I picked up a Puerto Rican girl from Bushwick with a neck tattoo and big hoop earrings who used to bag up drugs for me.

We pulled over on a deserted street in Williamsburg. Alex was distracted, talking on his phone. I lowered my window, got out of the car, took the gun out of the trunk, stuck the barrel through the open driver’s side window, and shot him to death. Then I drove away, with Alex dead in the passenger seat. The girl jumped out at the next red light and ran. On a quiet block, I pulled over again and hauled Alex’s body into the trunk.

I picked up an old heroin addict with construction worker hands to help me get rid of the body. He wrapped, he taped, he tied. I couldn’t do it. I remember driving away from the pier in Sheepshead Bay, high on heroin myself, taking deep drags on a Newport, thinking about next steps. No body, no crime scene. An associate of mine who owned a body shop fixed the bullet holes in the rental car. When I picked it up, I told him I was never there. He nodded.

A month later, I was picked up on a warrant for a gun charge and was back on Rikers. Once locked up, I kept getting rearrested. An indictment came down for selling heroin to an undercover officer who had infiltrated my circle. In February 2002, I read a Daily News clip that said the body of a black male had washed ashore in a laundry bag on a Brooklyn beach. Then, that summer, there was another indictment—for second-degree murder. The girl with the neck tattoo had told another drug dealer, who got busted; he told detectives about a white boy who had killed another dealer.

My mother, by then a real estate broker in Brooklyn, hired a good lawyer. She knew I did it. She told me to keep my mouth shut—that keeping a secret was a sign of maturity. I felt for Mom. If I won at trial, I was definitely going to continue being a criminal. She might easily end up like Alex’s mother, who had also paid a lawyer to help get her son acquitted in 1996 and now sat in another Brooklyn courtroom hoping for justice for her son’s killer.

When the prosecutor showed a blown-up photo of Alex’s shot-up body to the jury, she wailed. I hid behind my lawyer with my chin tucked to my chest. I felt horrible but I played my part, feigning incredulity when witnesses pointed at me, staging outbursts of indignation, committing perjury. The show almost worked: the first jury deadlocked; the second jury convicted. I received a sentence of twenty-five years to life for the murder, and three more years on top for selling drugs.

*

In 2004, I was moved to Clinton Correctional Facility, in Dannemora, upstate New York. I came up with a ninth-grade education, passed the high-school equivalency, then there was nothing to do. I used heroin to cope, and manipulated my mother into making Western Union payments. I hung out with the in-crowd white guys and joined in the prison politicking. This guy is good: he’s a gangster. This guy is no good: he’s a rat, or a rapist. This all went on in the yard.

Clinton’s yard was notorious as perhaps the most dangerous in America. According to a New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision report, Clinton had an average of seventy-one inmate-on-inmate assaults every year from 2005 to 2014, many involving a shank (an improvised blade or ice-pick). I had not been there long when I saw my first stabbing. A Puerto Rican gang member told me to stay off the Flats, a football-sized area in the yard, because someone was about to get stabbed. Moments later, one of his crew did the hit. Stabbed twice under the arm, the wounded man stumbled over to the guards. The next morning, the hitter strutted into the mess hall, beaming.

Despite what I’d learned long ago on Rikers, I didn’t want to be a part of the kind of prison violence that involved shanking and could end in my killing someone again.

In 2006, I was caught with contraband in Clinton and shipped to the Upstate Correctional Facility, a shiny new hell of double-bunk solitary cells. Small food portions left me starving at night. When I asked the guard for a few extra slices of bread, the tray slot on my solitary cell shut in my face. “I must fight… the monotony that will bury me alive if I am not careful,” Abbott writes about solitary. “I must do that, and do it without losing my mind. So I read, read anything and everything.”

It was in solitary that I first read Abbott’s words. I sent Mom a list of books suggested by my cellmate, a bookish white guy who was in for shaking a baby to death. When the package arrived, works by Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck, Trumbo, and Orwell spilled through the slot, along with Abbott’s slim book of angry letters. “If I were an animal housed in a zoo in quarters of these dimensions,” Abbott writes, “the humane society would have the zookeeper arrested for cruelty.”

Abbott had a finger-in-your-face bellicose tone. Everything was war. He used words like “convict” and “comrade.” Guards were “pigs.” “The only time they appear human,” he writes, “is when you have a knife at their throats.” In the Belly of the Beast can be a false friend for an impressionable prisoner. Yet Abbott can also be inspiring. Being an autodidact and declaring that the most dangerous prisoners are readers and writers—that resonated for me, in solitary, with my pile of books and aspirations of becoming a writer.

In 2007, after nearly six months in solitary, I was transferred to Attica, near Buffalo, the most fearsome prison in the state. I landed on a tier with one of my old cronies from Hell’s Kitchen and loaned him In the Belly of the Beast. He loved it. Weeks later, an ex-boyfriend of Alex’s sister moved into the same cell with me. He was looking for revenge. That was my luck. We had a brutal fight. I was losing, bloody, trapped, fear took over and I yelled out to the guards for help. That violated the convict code. My buddy from the Kitchen stopped talking to me and kept Abbott’s book. I didn’t ask for it back. I didn’t want it back.

Years later, working on this piece, I started reading Abbott again. Today, I connect most with his interspersed periods of vulnerability. “I’m tenuous, shy, introspective, and suspicious of everyone,” Abbott writes. “A loud noise or false movement registers like a four-alarm fire in me.”

In 2008, seven years in to my term, I was in Green Haven in Dutchess County. There I saw a familiar face from the Brooklyn projects, another friend of Alex’s. He was finishing a one-year pre-college program while in prison and told me he was trying to make a change. It didn’t seem as though he wanted to exact revenge on me for what I did to Alex. As time passed, though, prison politics escalated the situation: people were taunting Alex’s friend, inciting him—“Whiteboy killed ya man, and you ain’t gonna do nothin’?”

“You learn to smile him into position,” Abbott writes about handling someone like me. “To disarm him with friendliness.”

It happened in Green Haven’s yard. Everyone knew, except me. Alex’s friend greeted me with a handshake and half a hug. When I turned, he grabbed my arm, twisting my shirt and stabbed me with an ice pick six times in the side of my chest. He walked away, smoothly. Everyone saw it. The guy got away with it.

“The law has never punished anyone for hurting me,” Abbott writes.

I spent the next few days in an outside hospital. The pick hit an inch from my heart, the doctor told me, as she patched up my punctured lung. Part of me felt I deserved it. Part of me respected it. I killed Alex, his friend tried to kill me. I kept my mouth shut. My peers respected that I didn’t snitch, but I lost respect for another reason. Because I didn’t stab the guy when I first found out he was scheming on me, it made me look weak.

“In prison society you’re expected to put a knife in him,” Abbott writes.

Abbott’s vignettes of violence were visceral but often overwrought. In one prison, he wrote, thirty to forty bodies were found shanked to death; across America, he claimed, four prisoners a day suffered violent deaths. He never supported these numbers with evidence, and even today, with about two million people behind bars, those numbers don’t check out.

Yet I don’t doubt his suffering. He experienced violence in prison until his death. In 1999, Abbott sued the administration at Attica, the upstate New York facility famous for the 1971 inmates’ uprising and its bloody suppression when guards and troopers retook the prison, killing thirty-nine people, including ten hostages. In his harassment suit, filed by a Buffalo activist attorney named Michael Kuzma, Abbott claimed that the guards intentionally cut the electrical supply to his cell. The case was dismissed; harassment claims—or any kind of claim—were difficult for prisoners to substantiate.

Shortly after prison officials were served with the court papers, Kuzma told me, a prisoner attacked Abbott, then fifty-six years old, with a blunt object and fractured his face. Kuzma said Abbott told him it was payback, instigated by the guards, for the lawsuit. After the assault, Abbott was moved to a small, maximum-security facility nearby.

In June 2001, he was denied parole. The following February, he was found dead. Kuzma suspected foul play, so he had Abbott’s body shipped to Pittsburgh for an autopsy by a renowned pathologist, Cyril Wecht. Wecht found Abbott’s death to be consistent with suicide. When I spoke to Kuzma recently, on a phone call from Sing Sing, and asked why he’d done this for Abbott, he told me that he saw it as a moral obligation and wasn’t willing to accept the word of prison officials.

After the assault in which I was stabbed, I was transferred back to Attica. Despite what Abbott had experienced there, and my own earlier encounter, Attica turned out to be where I discovered the best opportunity of my life. In 2010, I joined the Attica creative writing workshop taught by Doran Larson, a Hamilton College English professor. A compassionate intellectual in a fedora, Larson was on a mission to share his skills with a dedicated half-dozen of us, with the hope that we would go on to publish our work. By the time I joined, some were publishing in literary journals; others had contributed to a book of essays that Larson edited called Fourth City, referring to the metropolis-sized population in America’s jails and prisons—some 2.3 million people.

In 2013, when I was thirty-six, I published my first essay, in The Atlantic. It was about my life of crime, how easily I’d obtained illegal firearms, and my ideas about gun control. After that, I became cocky, pressing my peers to be more forthright about their crimes, telling them that readers were naturally nosy, and editors wouldn’t publish them if they were coy about what had landed them in prison. It was easy for me: the prison pecking-order referred to my crime as “a good one” because I had killed someone “in the life,” as we called it—someone who sold drugs, toted guns, and had likely killed someone himself. Most of my classmates, on the other hand, had committed so-called “bad”crimes—such as the murder of a girlfriend or wife—and these men lived in shame.

“The model we emulate,” Abbott writes, “is a fanatically defiant and alienated individual who cannot imagine what forgiveness is, or mercy or tolerance, because he has no experience of such values.”

I understand now a little better how I was both rationalizing my crime and romanticizing it in ways that still bleed into my writing today. I regret my arrogance in lecturing my classmates, because they helped me to become a better writer. When Abbott’s name came up in our workshop, Larson said that his actions had set back prison writers twenty years—a sentiment I later found echoed in Jack and Norman. “After Abbott, prison writers were largely seen as merely gifted con artists,” Loving writes. “The liberal press and literary organizations were urged to give up their efforts at prison reform.”

When Abbott wrote In the Belly of the Beast, there were about 500,000 people in jails and prisons in the United States. By the end of that period, in the early Eighties, the average time served for murder, according to New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, was just six years. Today, it’s about seventeen years. I’d started my prison career right at the moment Abbott’s life ended, when the machinery of mass incarceration was going at full tilt, and the prison population had grown at least sixfold since 1972, around the time Abbott started his second long spell in prison. Being of a different generation to Abbott, I found Larson’s and Loving’s arguments persuasive. And yet, today I have this career. I have this voice.

Abbott’s take on convicted murderers getting out of prison and not coming back is supported by numbers. But it likely has less to do with their viewing life as “precious and fragile,” as he suggests, than with their simply aging out of crime. A 2011 report tracked 860 people convicted in California released since 1995. Only 1 percent committed new felonies, and none were for murder. By contrast, a 2018 Justice Department report found that 21 percent of all prisoners released in thirty states in 2005 and tracked over a nine-year period were re-arrested for an offense involving violence within three years of their release. To this end, releasing people convicted of murder into society has little risk—and what makes Abbott exceptional, along with his writing, is that he killed again after serving so much time.

In recent years, movements for prison and criminal justice reform have shifted public opinion away from the retributive reflexes of the Clinton crime bill and the mass incarceration policies of the Nineties and early Aughts. Abbott bragged that he’d never participated in a prison school; yet, at least today, I can write an op-ed in the paper of record pleading with politicians to reinstate the Pell Grants that used to fund the college programs that he mocked.

I can appreciate Abbott’s pain, the power of his writing, its expression, raw and vulnerable. But I can’t say, as Mailer did of Abbott, that the prison system itself made me worse. In fact, being here may have saved my life. In my younger years, despite the difficulties of my childhood, I certainly had more opportunities than Abbott and most of my peers in prison did. I chose to squander them: I sought out “the life,” sold drugs, lured Alex to his death, pulled the trigger. I chose all that. In prison, I choose to commit myself to writing and rewriting the words on the page, sitting on an upturned bucket until my ass is numb and my back burns.

*

“I want consolation more than anything in this world,” Abbott writes. Abbott wanted to be heard, and Mailer wanted to listen. Being connected to a famous author like Mailer must have made Abbott feel that he mattered.

I remember telling my sponsor, an investment banker and a volunteer who brought AA meetings into Attica, that Esquire was interested in publishing a story I was doing about the mental illness crisis behind bars. He congratulated me, but also offered a knowing smile. I was chasing prestige and he recognized in that transparent need that I could all too easily substitute one addiction for another. I was five years sober then, but sure enough, I relapsed and started popping the muscle relaxers that prisoners would get from the medication line, hold in their mouths, spit out when they were no longer under observation, and deal later. I stopped praying, stopped helping others, and started acting like a jerk again. Eventually, I came to the realization that my reform through writing could only be sustained in my sobriety.

In the March 12, 2009, issue of the Review, some of Mailer’s letters to Abbott were published. His letter to Abbott of 1979 addresses Abbott’s drug use. “And I would say to you that what I found most disturbing in all your thoughts is that what you like,” Mailer writes, “you adopt and adapt automatically to your intellectual system. You need drugs in order to alleviate the soul-killing monotony of prison, so drugs are part of your system.”

At Abbott’s last day of trial, Mailer pleaded with the press. “Adan has already been destroyed,” he said, “at least let Abbott become a writer.” Then he said, “a democracy involves taking risks.” I’ll admit, reading this made me feel envious, and a bit confused. I didn’t quite understand Mailer’s implicit point that Abbott needed to be free to become a writer. Wasn’t the idea to reaffirm literature itself, in Mailer’s words, “as a human expression that will survive all obstacles”?

In an earlier draft of this piece, my editor told me that I sounded competitive with Abbott and suggested I ease up on him, that I hadn’t yet myself faced the challenges of release, and that the reader might ask, “How do we know Lennon will be different?” There was trust and risk involved with Abbott, he reminded me, and there’s trust and risk involved with me. Fair enough. My prison pedigree, though, is hardly on par with Abbott’s. I don’t see myself as a risk, as Abbott was, to prison order or the safety of society. I’ve also already earned trust from colleagues in journalism as a writer from prison, without a famous writer’s championing my cause. Even so, I try not to see my writing as a passport to freedom so much as I see it as my life’s purpose.

Writing would not be Abbott’s salvation. When his second book, My Return, did appear, in 1987, it was another nonfiction—at least in form, if not in fact. In it, Abbott claimed that Adan, the man he’d killed outside the New York diner, had had a knife. Mailer had declined to write an afterword. By then, Abbott was back in Clinton Dannemora, at the beginning of his sentence of fifteen years to life.

Although he and I never met, I can almost picture us in adjacent cells in Clinton, the air dry with pulsating heat, holding hand-mirrors through the bars of our cell doors so that we could see each other to talk. In my imagination, I’d suggest to Abbott that this wasn’t the right story to tell because it showed no remorse. Maybe I’d suggest a different narrative. Most likely, he would have rejected my advice, and we would have never spoken again. It’s like that in prison.

I’ve talked about remorse with other prisoners only a handful of times. Before her Parkinson’s Disease made the journey impossible, Mom used to come and see me in Clinton and Attica on family reunion visits, which involved a forty-eight-hour stay in a furnished module-home compound inside the prison wall. She’d sometimes mention how Alex’s mom could never be with him, and how grateful she was to spend time with me. We’d talk about the two trials, how scared she had been of facing Alex’s family, how one time in the courtroom hallway she met his mother, hugged her, said she was sorry, and they both cried.

Mom nudged me toward remorse and grappled with her own shame at what I’d done and where she went wrong. Sometimes I’d go silent and feel her watching me. I was her kid, and I was a killer. “Murder was permanent… I wanted you to know what you did,” she told me on a recent call. “Today, you are the man I wanted you to be. You are more than I ever expected.”

No doubt, Alex’s mother had hopes for him—he was insightful and ambitious. He could’ve done more with his life, even if he were in prison like me. It’s wrong for me to take a snapshot of Alex as he was before he died and tell myself I’m not so bad because I killed a criminal—and then, in the same breath, say that my character should not be defined by my crime. I finally realized that I had to fully account for the murder before I could gain acceptance as a writer.

Over the years, journalism has helped me feel empathy, and this sort of essay-writing has helped me with remorse. Letter-writing is an art, and Gilmore and Abbott were naturals. They had the ability to connect with the other person, right from the heart, and almost certainly without needing endless drafts. But narrative writing is all about rewriting. The process itself, trying to understand a character’s goals and motivations—my subject’s, my own—while shaping the story, is like months of therapy sessions, stripped down, the most vivid scenes and self-realizations left on the page. My editor is my sounding-board: “John, you do realize how you sound when you say…” Checking ego, voice, tone, pace—editors have not only made my writing sharper; they have helped me think and understand myself better.

I may still live in a cell, in Sing Sing, but in my mind I am no longer a criminal. I write, I publish, I earn money, I pay taxes. I walk a dangerous line, hoping to earn the respect of colleagues and readers out there, while attempting to maintain the respect of my peers in here.

As I’ve changed, prison has become much, much harder. A couple of years ago, a guy from my neighborhood in Brooklyn landed in Sing Sing. He’s a few years younger, a Mad Hatter type who aspires to be muscle for the mob when he gets out. He remembers me and Alex and our reputations. He romanticizes the murder I committed. He recently commented that in prison I became a civilian. He meant it as an insult: I couldn’t be counted on, if the situation arose, to stand shoulder to shoulder with him and the others in the yard. He’s right. He senses that I’ve softened. I have. I can’t get away from men like that. I feel trapped. This is my punishment.

“Always I burned, truly burned, with the need to leave prison,” Abbott writes, “to be free; to get away from this thing that was destroying my life irrevocably.”

I’ve been incarcerated for almost eighteen years now. I’m often anxious, always depressed. My work gives me relevance, but I still feel irrelevant. I find optimism when my peers tell me I inspire them. It makes me want to create the same sort of workshop in Sing Sing that helped me find myself as a writer in Attica. I would like to invite the best editors and writers from New York City up here, a forty-five-minute ride away on the Metro North.

I think about the people I hurt. I never want to do that again, and I’ve made a pledge to myself not to. Alex had siblings—he was closest to his younger sister—who miss him and will hate me fiercely and forever. I know that. I think often of something Alex’s sister quoted at my sentencing hearing: “Only the man who has enough good in him to feel the justice of the penalty can be punished.”