On a sweltering afternoon in late July, not long after visiting the US-Mexico border, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez hosted a town hall at a public school in Corona, Queens, New York. The subject was immigration. Three weeks earlier, the Democratic congresswoman had toured a migrant detention facility in Clint, Texas, where she observed women drinking out of toilets; her denunciation of these conditions earned her death threats, sexually violent insults, and an attack by President Donald Trump. Now, outside the town hall, protesters braving hundred-degree temperatures held up signs that read “THANK GOD FOR TRUMP.”

Inside the school, in an air-conditioned auditorium with a carved wooden stage, Ocasio-Cortez’s staff members set up a folding table and pinned the Congressional seal to the podium. Police officers and burly security detail whispered into radio microphones on their collars. Ocasio-Cortez’s district director, Maribel Hernández Rivera, reviewed the agenda and gave a quick interview to a Spanish-language talk show. “I’m excited, and I’m nervous,” she said, “because of the way things have been escalating in Washington.”

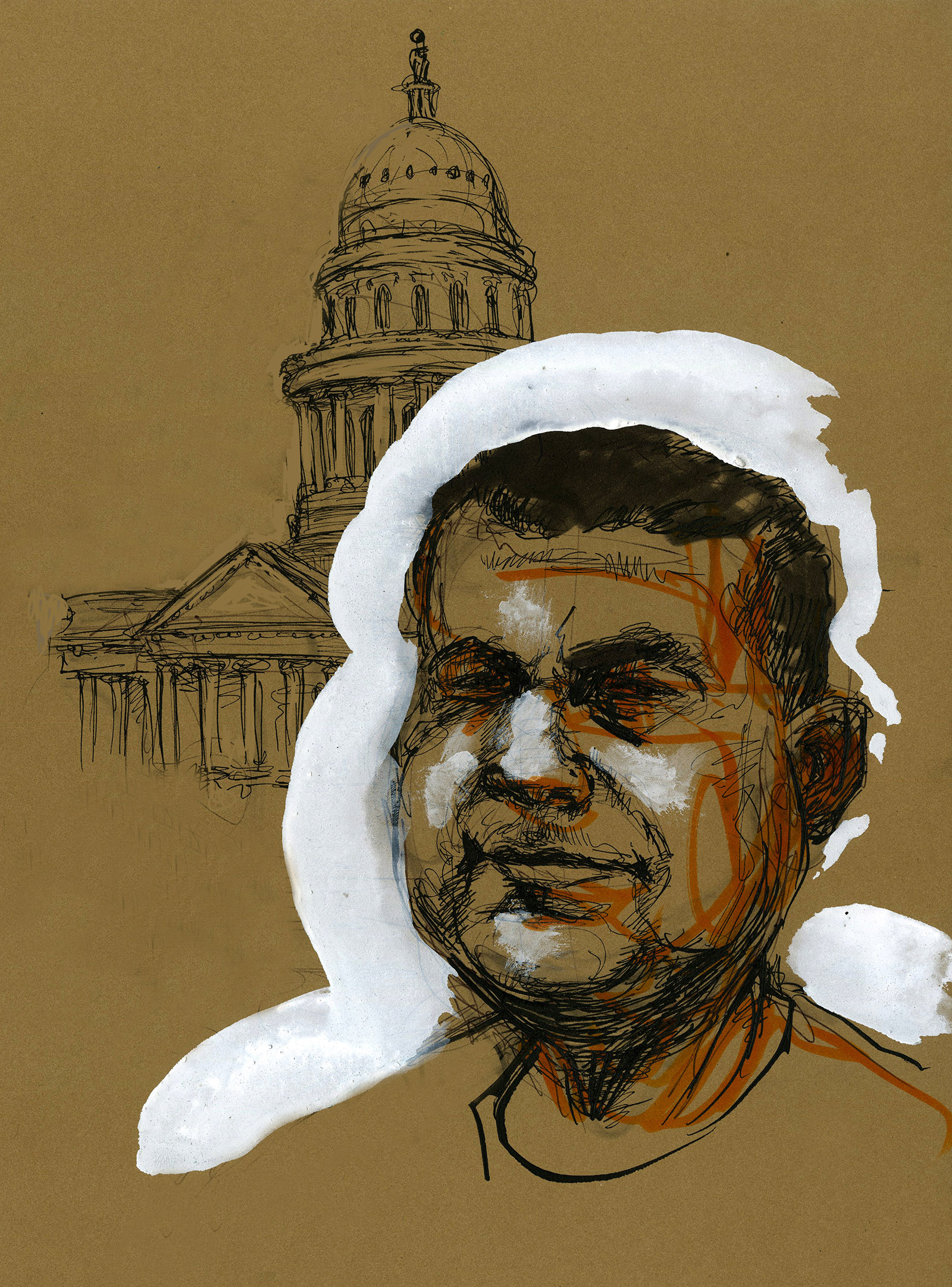

Hernández Rivera, a thirty-eight-year-old immigrant from Mexico, joined Ocasio-Cortez’s staff in January, after nearly a decade working as an immigration attorney and overseeing a legal-aid program in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Office of Immigrant Affairs. Ocasio-Cortez, she told me, “was the first politician I’d ever heard talking about abolishing ICE. She understood that an agency capable of breaking families apart is an agency that can’t be redeemed.” During her first six months in Ocasio-Cortez’s office in Jackson Heights, one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the US, Hernández Rivera had already helped respond to more than two hundred requests for assistance from constituents in Queens and the Bronx. “Ninety percent is immigration-related,” she said.

Before the town hall, she and Ocasio-Cortez huddled in a makeshift green room with panelists drawn from the community. The congresswoman gave a quick pep talk and signed an AOC and the Freshman Force comic book for one participant’s daughter, then led the group into the auditorium, to joyful applause from a mostly brown and black crowd. As Ocasio-Cortez offered an emotional recap of her trip to the border and an inventory of Trump’s assaults on immigrants, seven interpreters translated her words, each into a different language. The speakers to follow embodied the daunting circumstances Hernández Rivera deals with in her office: a Latina DREAMer whose brother was deported, a South-Asian organizer against police violence, a Chinese-American housing activist, an advocate for often-neglected immigrants from Africa, and a Nepali food-delivery worker with Temporary Protected Status (TPS).

TPS is not on most people’s minds when it comes to the current immigration crisis. Understandably, news coverage tends to focus on workplace raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the concentration camps warehousing adults and children across the Southwest, and the “Muslim travel ban” that, with the Supreme Court’s blessing, still prevents transit between the US and seven countries. But TPS, along with a related program called Deferred Enforced Departure (DED), grants shelter in the US to some 400,000 people from countries deemed unsafe: currently, Sudan, South Sudan, Nicaragua, Haiti, El Salvador, Liberia, Honduras, Nepal, Syria, Somalia, and Yemen. Created thirty years ago and rooted in international humanitarian law, the program protects foreign nationals from being deported to danger. Many recipients of TPS have lived in the US for ten, or even twenty, years. They have homes, careers, and, often, US-citizen children.

In October 2017, the Trump administration announced that it would terminate TPS for Sudan. Further terminations—for Nicaragua, Haiti, El Salvador, Liberia, Nepal, and Honduras—soon followed. Without the benefit of this status, hundreds of thousands of people will face the miserable choice of either staying in the US without permission, forced underground and unable to work lawfully, or returning to an unstable, perilous “homeland” that some of them barely know. It will mean yet another form of family separation.

The stakes are such that, last fall, a federal court in California ruled that all such TPS designations should be preserved for the time being, while it decides if terminating the program was constitutional. This week, on August 14, a federal appeals court will hear oral argument from attorneys for the Department of Homeland Security, on the one hand, and TPS holders, on the other, as to whether the terminations should occur as originally scheduled.

For Hernández Rivera, the litigation is personal: her husband, Giddel Contreras, is a TPS holder. A native of Honduras, Contreras has been in the United States for nearly twenty-five years, but was undocumented until he got TPS. His thirteen-year-old daughter, Madison, Hernández Rivera’s stepdaughter, is a US citizen.

Advertisement

Families like theirs live in a kind of suspended animation, faced with unsettling decisions. For Hernández Rivera and Contreras, there is, for starters, the matter of their apartment lease, which is up in October. Should they renew? And if the court allows TPS to be canceled, should they leave the country together or live apart? Where will they go? If they both depart, and Madison lives full-time with her mother, how often will they see one another?

These questions hung in the air at Ocasio-Cortez’s town hall, which Contreras and Madison watched from the second row. “The White House and USCIS are grinding processing of legal cases to a halt,” the congresswoman told the crowd. “They are eliminating DACA, they’re closing TPS for our Nepali neighbors, for folks from Honduras. They are denying areas of TPS where we should be having them, for folks from Venezuela, for example… They are forcing people to become undocumented.”

If the president gets his way, Contreras will lose his right to remain in the country on January 5, 2020, in less than six months’ time. As Ocasio-Cortez spoke, Hernández Rivera, wearing an “I AM AN IMMIGRANT” T-shirt, nodded from her seat onstage, her forehead furrowed into a tight knot. Contreras and Madison sat stoically. “Do you know all this stuff?” I asked Madison. She nodded.

*

Temporary protected status dates back to a period of what seems, by today’s standards, like unimaginably productive lawmaking. In 1990, just four years after President Ronald Reagan signed into law a broad reform granting legal status—also known as an “amnesty”—to nearly two million undocumented people, his successor, George H.W. Bush, authorized another comprehensive immigration law. The Immigration Act of 1990 increased the number of immigrants admitted annually to the US, with special provisions for highly educated workers, refugees, and Irish citizens. It also created a program granting “special temporary protected status” to migrants from El Salvador, where a civil war had already killed tens of thousands of civilians, and empowered the government to give TPS to other foreign nationals in the future. TPS was intended as a sort of humanitarian backstop: whereas people applying for asylum or refugee status had to meet narrow, individualized assessments to be in the US, a designation of TPS lent group relief to documented and undocumented migrants who could not, in good conscience, be returned to their places of origin—on account of armed conflict, a natural disaster, or general instability.

As its name suggests, TPS is approved for durations of between six and eighteen months at a time, but, in the case of troubled states like El Salvador and Honduras—where Contreras is from—it has been in effect for decades. Temporariness “loses meaning when you renew it over and over for twenty years,” explained Emi MacLean, a legal director at the National Day Laborer Organizing Network and an attorney for TPS holders in federal court. “Another way of thinking about it is that it’s something for a temporary period, like a driver’s license or a law license—a time-limited period, which doesn’t mean you can’t renew it.” Ordinarily, as the end-date of a country’s TPS designation approaches, the government decides whether to extend or terminate the program. In the past, to make these assessments, the USCIS has tapped the State Department’s human-rights reports and consulted with the foreign governments in question to evaluate conditions on the ground, in real time, not just in relation to the circumstances that first triggered TPS.

Over the past three decades, the US has extended TPS to people from countries as diverse as Bosnia-Herzegovina, Rwanda, and Lebanon, giving hundreds of thousands of people the opportunity to live and work legally; TPS is available to undocumented immigrants as well as to visa-holders. This has benefited not only individual TPS recipients and their families, but also their home countries (which take in remittances and are saved from population growth in times of upheaval) and the US (which takes in their tax dollars and labor). A 2018 report by the Center for Migration Studies found that TPS holders are unusually productive: more than 80 percent of the three largest groups—from Honduras, Haiti, and El Salvador—are employed, compared to 63 percent of the general US population; together, these immigrants are raising 273,000 US citizen children.

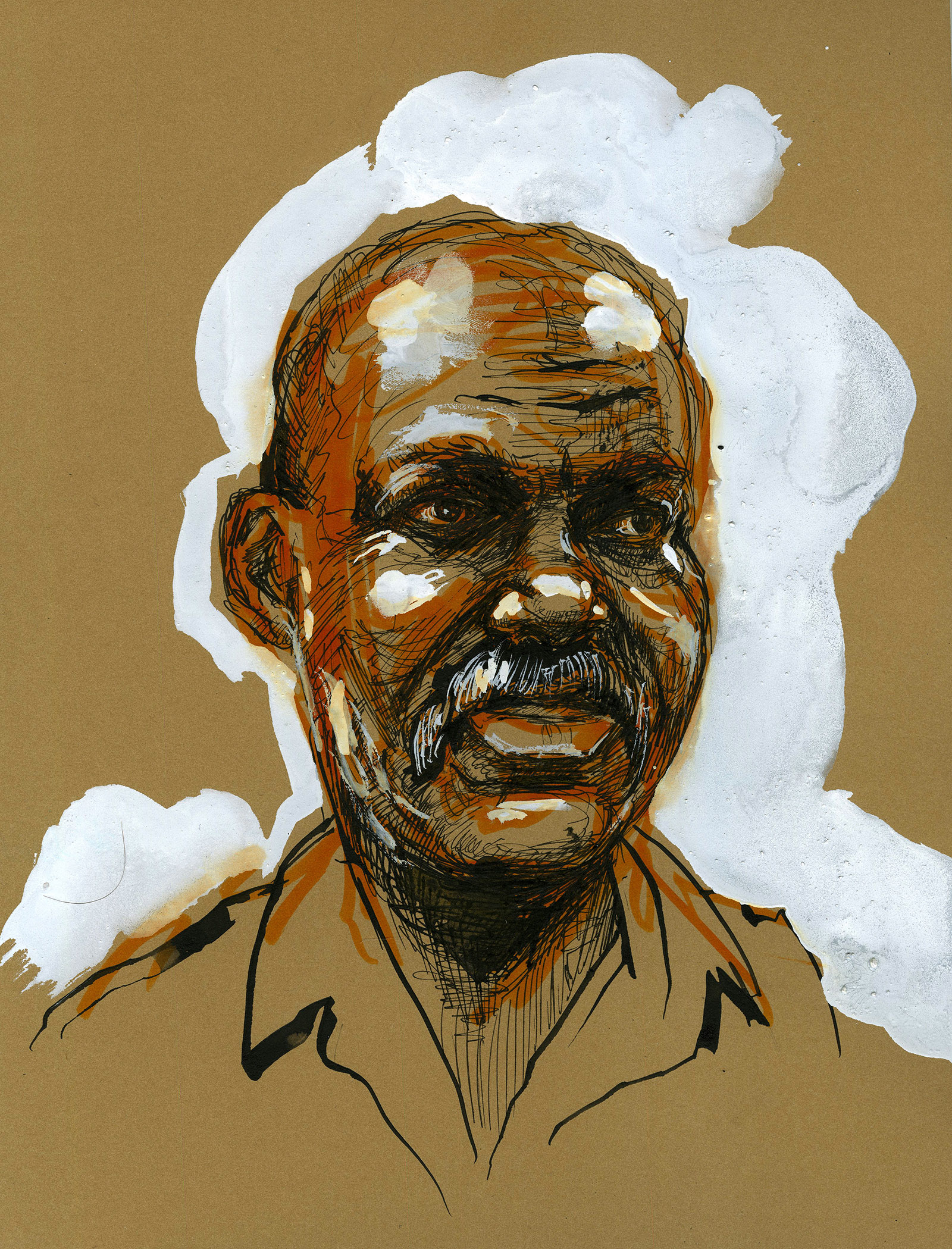

Contreras is typical in this regard. He came to the US from his coastal home town in northern Honduras, in 1995, to earn more than a poverty wage and send money back to his family. He worked in Texas, then New York, where his uncle was living. In 1999, when Hurricane Mitch flattened large swaths of Central America, President Clinton designated immigrants from Honduras and Nicaragua as eligible for TPS. Contreras was undocumented, so he initially hesitated to apply. “The lawyer who helped me with the paperwork said, ‘It’s only for six months. It’ll be temporary.’ I said, ‘Oh, okay,’ and that six months turned out to be many years. Many, many years.”

Advertisement

After Hurricane Mitch came further storms, droughts, a dengue epidemic, and lethal political unrest in Honduras—in 2011, two of Contreras’s cousins were found murdered—so TPS held for Contreras and tens of thousands of others. Contreras settled in New York and found his calling in the restaurant business. He had his daughter Madison, met and married Hernández Rivera, became a bicycling fanatic, earned his GED, and graduated from culinary school. He now works as a sous-chef at The Pierre, a five-star hotel in Manhattan.

By the time President Obama left office, immigrants from thirteen countries on four continents benefited from either TPS or DED. They were among the country’s most well-documented foreign nationals, required to show up for regular fingerprinting and check-ins with the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), part of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Between the fall of 2017 and the summer of 2018, however, the Trump administration announced imminent end dates for 98 percent of all such recipients (excluding only those from Yemen, Syria, Somalia, and South Sudan).

Trump’s cascade of TPS cancellations was radical—and their announcement was shaded by his racist and xenophobic rhetoric. Trump has said that immigrants from Haiti “all have AIDS” and that people from Africa would, once allowed into the US, never “go back to their huts.” In a meeting with members of Congress specifically about TPS for Central Americans and Africans, Trump notoriously asked, “Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?” He suggested that that Haitian immigrants, in particular, should be excluded from any compromise plan.

Several lawsuits filed by TPS holders allege both that the DHS spurned administrative rule-making and acted in a racially discriminatory manner. Last October, in one of these cases, a federal judge in San Francisco granted a preliminary injunction to TPS recipients from El Salvador, Haiti, Sudan, and Nicaragua, halting termination of the program. (Later, the injunction was extended to Honduras and Nepal in a parallel case.) The court found that the DHS had acted unconstitutionally, “based on animus against non-white non-European immigrants,” and in order to justify the cancellation of TPS, a “pre-ordained result desired by the White House.”

During the parties’ routine exchange of documents, the plaintiffs obtained a disturbing cache of correspondence from the DHS and the White House. These documents showed that the administration was so intent on ending humanitarian relief that it instructed career civil servants to bypass longstanding rules and procedures. It also invented a new standard for renewal: looking only at “the conditions on the ground as impacted by the initial event,” not current conditions. Stephen Miller, Trump’s policy adviser and architect of many newly restrictive immigration policies, urged the DHS to get rid of the program.

His ally inside the agency, Robert Law, who, before Trump entered office, worked at the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR)—which the Southern Poverty Law Center considers an anti-immigrant hate group—instructed subordinates to downplay the severity of Haiti’s conditions so that the agency could arrive at “the conclusion we are looking for.” And Frank Cissna, who would soon become director of the USCIS, berated his staff for drafting a Sudan decision memorandum whose findings—that the country continued to be unsafe—did not match the recommendation to terminate TPS. Cissna wrote in an email:

The memo reads like one person who strongly supports extending TPS for Sudan wrote everything up to the recommendation section, and then someone who opposes extension snuck up behind the first guy, clubbed him over the head, pushed his senseless body out of the way, and finished the memo.

Homeland Security made these decisions in spite of substantial evidence that the countries at issue are still in crisis. In the fall of 2017, the Department of Defense and the US Southern Command recommended against terminating TPS, citing, in the case of Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Honduras, the danger of spurring “further irregular migration to the United States,” and, in the case of Sudan, undermining US “defense interests” in the region. At a panel discussion last year, hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., the Salvadoran ambassador to the US, Claudia Ivette, admitted that her country was not economically stable or safe enough to be able to absorb the 200,000 TPS holders from El Salvador. Her counterpart from Honduras, meanwhile, estimated that, in the event of TPS’s termination, 90 percent of Honduran TPS holders would remain, undocumented, in the US.

Amaha Kassa, the executive director of the nonprofit African Communities Together, has seen this firsthand. After TPS was terminated for Guinea and Sierra Leone, he told me, people simply stayed on: “We’ve been helping them through their undocumented status,” he told me. “They wanted to know, what does it mean to find work without work authorization? What does it mean for getting a driver’s license? And is it possible to apply for other relief, like amnesty?” On every front—getting a job, avoiding deportation, caring for children—everything became harder without TPS.

*

In June 2017, rattled by Trump’s early executive orders—against sanctuary cities, migrants from Muslim nations, “aliens who illegally enter” from Mexico, and workers on H-1B visas—a group of TPS holders gathered in Washington to form the National TPS Alliance. Never before, in the thirty years of TPS, had the program’s beneficiaries felt obliged to organize in its defense, but this new formation was prescient. Within months, they would sue the Trump administration for terminating TPS and DED, and lobby for a permanent fix in Congress.

In August 2018, activists with the Alliance boarded a blue bus labeled “TPS Journey for Justice” and crossed the US, making forty-four stops in twelve weeks. This past June, they succeeded in lobbying the House to pass the American Dream and Promise Act, which would give long-term beneficiaries of TPS, DED, and DACA a path to permanent legal status—similar to an existing pathway in Canada. On August 14, Latino, African, and Nepali TPS holders from around the country will attend the oral argument in California.

Contreras kept tabs on these developments, but preferred to focus on work and an upcoming vacation. “Honestly, I’m not into politics,” he said, when I joined the family for tacos at their Manhattan apartment. “I just don’t think about it too much, but yes, it has gotten more intense for everybody. All these people who don’t want immigrants here are actually saying so, whereas before, they didn’t want to say it too loud.” Madison buried herself in school and the cheerleading team; her dream was to become a pediatrician. “It’s really hard for me to imagine losing my dad after all these years, and I’m scared,” she told me. When I asked her if she wanted to get involved in TPS activism, she replied, “No, that’s Maribel’s job!” and laughed.

Hernández Rivera, though trained as an immigration attorney, is now more of a troubleshooter and policy adviser, both in Ocasio-Cortez’s office and at home—where she and Contreras are doing their best to focus on “regular life.” “I always tell Madison, things are going to work out, one way or another,” she said. “If he has to go, she’ll get a scholarship and go visit.” Raised by an undocumented father, Hernández Rivera was herself once undocumented; she gained citizenship in 2008, through her stepfather. In theory, she could similarly sponsor her husband for a green card, but the USCIS would first have to waive an old deportation order: Contreras had entered the country without permission, then missed a hearing to adjudicate his status and was ordered to leave. “Maribel has been searching and searching for ways to make my situation a lot better, but unfortunately it hasn’t been possible,” he told me.

While the application for this waiver and the TPS lawsuit are pending, the family can only stand by. The congresswoman “knows our situation,” Hernández Rivera told me, but hadn’t yet been called upon to speak out. “There’s nothing that can be done at this moment, so where we are is waiting on immigration to decide our petitions. And also, right now, TPS is still valid. He still has status.”

The preliminary injunction has kept TPS in place, but many TPS holders are struggling to get their work-authorization cards renewed. Angela Hernandez, a fifty-four-year-old Salvadoran who’s lived and worked with TPS in Texas for nearly twenty years, told me that she’s been unable to find work for the past six months. The federal government published a note in the federal register, clarifying that work authorization for TPS holders is still good even if the holder’s ID card expires, but most employers do not care to digest the regulatory fine print. Salma Ahmed, who came from Sudan when she was just two years old and is now a college student in Chicago, said that Trump’s termination of TPS has begun to affect her life “on a day-to-day basis. It’s harder to apply for loans. It’s harder to apply for scholarships. I was driving with an expired license for a month and a half because they wouldn’t renew my license.”

Ahmed and her mother and father have TPS, while her two younger sisters are US citizens—a common mix in long-term immigrant families. Mauro Navarro, a warehouse worker and San Salvador native with TPS who’s been in the US for twenty-six years, has three children, all US citizens. Another Sudanese, Abubaker Ahmed (no relation), who arrived in America nearly a quarter-century ago and has had TPS almost as long, has a US citizen sister, wife, and daughter.

The situation of Angela Hernandez’s family in Texas is even more complicated: two of her children are citizens, one has DACA, and two are undocumented. I spoke with one of her US-born sons, twelve-year-old Angel Castillo. He hadn’t heard of the term “TPS,” but knew that something was going on with his mother’s immigration status. He told me that he feels “messed up inside” about how people like his mother and Mexican father are being treated. “I would say to the president that it’s important for our families and parents that come from different countries to stay with us, because we would not be able to work or get food or supplies, and it would be hard to learn things,” he said. “The kids, the newborns, it would be hard for them to be raised.”

While speaking with Angel, I thought of Madison and the deep unease felt by so many mixed-status families. TPS was never perfect, bounded by eligibility dates, renewal requirements, and steep fees: as a report noted last year, it “traps its (often long-term) beneficiaries in a legal limbo, denies them most federal public benefits, and prevents them from adjusting to LPR status”; it also fails to “offer durable solutions following termination or withdrawal of TPS status.” But Trump’s attempted elimination of the program has been devastating nonetheless, aggravating an already precarious situation. In a 2018 study of Latino parents, TPS holders reported high levels of psychological distress for fear of being cleaved from their family members; many said that they warned their children to avoid contact with the authorities. “I think about it—it’s only five months away,” Contreras told me in July. “When I think about leaving my daughter behind…” His mouth formed a long, flat line.

As the TPS lawsuit goes before the Ninth Circuit—and the Republican Senate continues to refuse a hearing on the American Dream and Promise Act—immigration attorneys and advocates are rushing to assist families. Tammy Lin, an attorney in San Diego and a member of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, has helped TPS and DED holders from terminated countries (Haiti, Liberia, Nepal) and non-terminated ones (such as Syria) renew their work-authorization documents, apply for green cards through US citizen spouses or adult children, and devise emergency plans in case of deportation. “When there were rumors that they were going to end TPS for everyone, there was a huge scramble by practitioners to get them residency,” she told me. If the administration’s decision to cancel TPS and DED survives the courts, then Lin will likely help many clients apply for asylum—though Trump has tried to curtail that form of humanitarian relief as well.

Hernández Rivera feels sober about the legal strategies being tried. “To be honest with you, I’m not super-hopeful on that end,” she said of the TPS lawsuit in California. “We’ve seen it again and again—the lower courts are one thing, but then, when it gets to the Supreme Court, they side with the administration.” It didn’t help that even the historically liberal Ninth Circuit has tilted to the right: a quarter of its active judges are now Trump appointees. Hernández Rivera seemed to put more stock in activism, and had compiled a checklist of tactics to campaign for her husband, inspired in part by Ocasio-Cortez’s savvy use of social media. “Everybody who knows me is aware of what’s happening. We have the phone numbers ready, emails ready, Facebook ready, Twitter ready,” Hernández Rivera told me. “We’re going to fight. We’re going to do everything we need to do.”

A few days before the oral argument, she and Contreras traveled to Miami. “I came here for my friend’s bachelorette party, but Giddel said, ‘Let me come, because this might be my last trip,’” she told me from their hotel room. “He’s making me aware that we have five months left. It’s really nerve-wracking. It’s very real now.”

This story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.