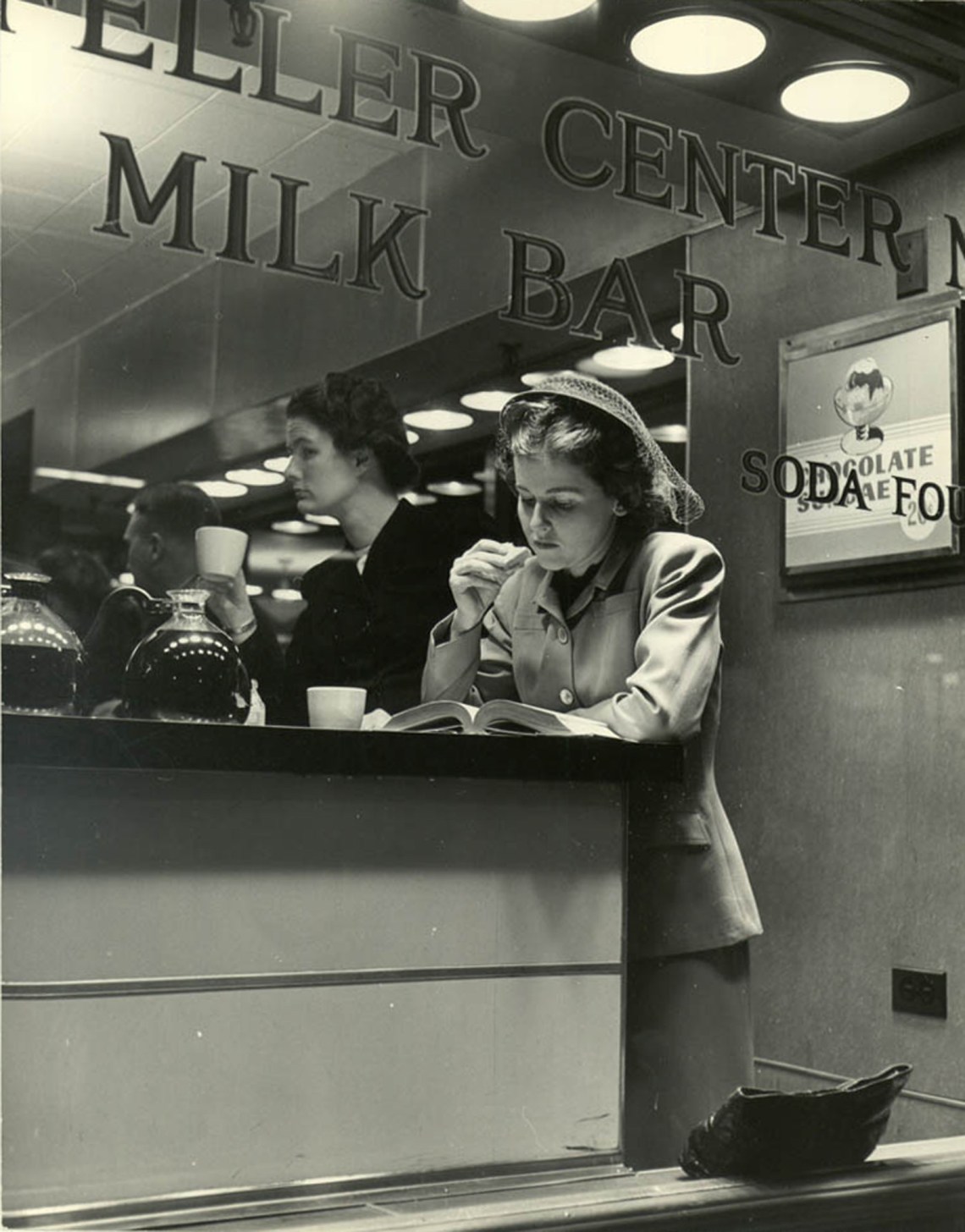

Beneath an arc of hanging laundry, a smiling woman stands at her ironing table, surrounded by a singular landscape: rows of beds to be made (thirty-five in all, the caption tells us) piles of folded clothes (250 pieces), a washing machine, a broom, piles of cans of food and bunches of carrots and other vegetables (174 pounds in all) to prepare, 400 pieces of silverware to wash. The caption reads, “A week’s work for Marjorie McWeeney is assembled by Bloomingdale’s store.” Valiantly smiling, McWeeney is dwarfed by her surroundings.

The photograph was taken by Nina Leen for a 1947 article for LIFE magazine titled “The American Woman’s Dilemma,” which profiled a selection of women, professionals or homemakers, in a fourteen-page spread. The subhead summed it up: “She wants a husband and she wants children. Should she go on working? Full time? Part time? Will housework bore her? What will she do when her children are grown?” The photographs, which include scenes of McWeeney dressed in various roles—as cook, laundress, nurse, seamstress, chauffeur, housemaid, even “glamour girl”—appear to be a humorous take on the subject from a woman who had herself chosen a full-time career over a life of domestic chores.

Russian-born Nina Leen, who immigrated to New York in 1939, was a contract photographer who joined LIFE’s staff in 1945. She is one of six women photographers featured in an exhibition, now at the New York Historical Society, on how these women’s work “contributed to LIFE’s pursuit of American identity through photojournalism.”

Magazine magnate Henry Luce launched his new magazine, LIFE, on November 23, 1936, convinced that pictures themselves could tell a story instead of simply illustrating text. It was the first successful photographic magazine in the United States, mixing politics with entertainment and popular culture. In barber shops, beauty parlors, trains, and homes, Americans thumbed through a magazine that originally cost a dime. Its weekly circulation soon far exceeded the company’s predictions, rapidly expanding from the first issue’s 380,000 copies to more than one million just four months later.

By 1939, LIFE had not only become profitable, but with a weekly circulation of 2 million—and 13.5 million just years later in 1945—it became the most widely circulated magazine in the world and would remain so until the 1960s. To its readers, LIFE could seem to be both a mirror and a lens, but always an optimistic one: a staunch anti-Communist and a Republican, Luce wanted to portray America as a united culture and a model for the world. He believed that Americans shared a basic set of values that transcended conflicts and diversity.

During the weekly’s entire thirty-six years of publication (1936–1972), however, the magazine employed very few women. Several were on staff, but most were contract photographers or freelancers. Photographer Inge Morath, who also published her work in LIFE magazine, once said: “Being one of the then rather rare women photographers… was often difficult for the simple reason that nobody felt one was serious (what does a pretty girl like you want in this profession?). Much male condescension… I certainly do not think that I got the same forceful male brotherhood support the men got.”

Each of the women highlighted in the exhibition has a different style and approach to assignments. Nina Leen and Margaret Bourke-White, for instance, could not be more different. Bourke-White, whom Luce brought into his first magazine, Fortune, in 1929 to cover business and industry, was hired in 1936 as the first of four staff women photographers at LIFE. She shot the new magazine’s first cover, photographing the gigantic Fort Peck Dam near Billings, Montana, a New Deal project in the Columbia River Basin. In her image, the massive dam, shot from below to accentuate its scale, is made of strong, stark lines, with an accent on geometry and light and shadow contrasts. It looks like a modern version of the Temple of Dendur, built by the Romans in Ancient Egypt.

Bourke-White was known for her tough personality and her courage. She worked her industry connections to obtain unprecedented access to cover the industrial revolution taking place in the USSR in the 1930s, making her the first Western photographer accredited to enter the Soviet Union. She also became the first female photographer embedded in World War II combat zones, and in 1945 she documented the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp. Her images were among the first to bring the attention of an unaware American public to the camps.

Advertisement

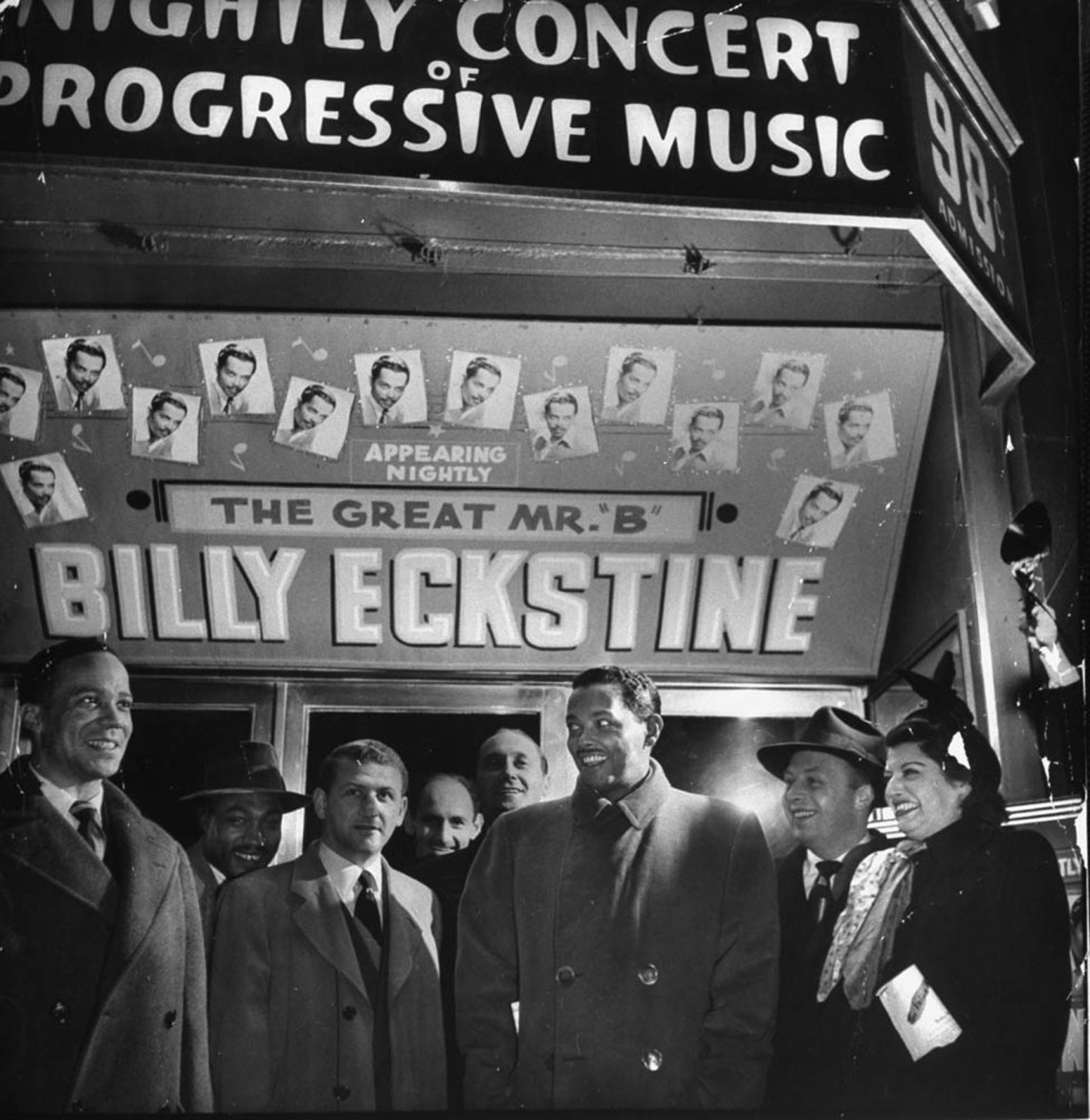

Martha Holmes, another photographer featured in the exhibition, was an art student when she was hired by The Louisville Times as a photographer’s assistant. She was soon promoted as a full time photographer when many of her male colleagues were called to service in World War II. She was just twenty years old when, in September 1944, LIFE saw her work and hired her. By 1947, she was one of the magazine’s staff photographers, and later continued her work there for three decades as a freelancer, including covering the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings. One photograph shows Humphrey Bogart, Danny Kaye and Lauren Bacall listening intently to a witness; another shows Bertolt Brecht being sworn in as the eleventh of the “Unfriendly Nineteen” before the Committee. In 1949, Holmes shot a photo essay on jazz singer Billy Eckstine.

Her favorite photo, enlarged for the exhibition, was of the singer surrounded by grinning female fans, one with her head on his chest. In an interview with the Pittsburgh Post Gazette in 2008, editor Bobbi Burrows said of the photograph: “It was groundbreaking back then in that it was a black man hugging a white woman… There was a discussion about whether we should run it or not. But Luce said, ‘Run it.’” Excerpted readers’ letters, included in the exhibition, demonstrate how shocking to the mainly white, middle-class readership the image was. One reader called it “the most nauseating picture of the year.” This is one of the rare instances when Luce chose to publish a controversial picture, which he most probably did more for its power to shock than for political reasons. Holmes herself was an empathetic and multi-faceted photographer, but not necessarily a politically motivated one.

Hansel Mieth, my favorite photographer in the show and certainly the most socially engaged, drew from her own experience to imbue her pictures with empathy and emotion. She believed that “to be a good photographer, you must feel what people feel when they’re down.” Mieth had left Germany when she was eighteen, arriving in the United States in 1930 in the midst of the Depression. She initially worked as a seamstress, but soon she and her husband, Otto Hagel, became migrant agricultural workers. Appalled by the working conditions, they acquired a second-hand Leica camera and photographed their experiences. They contacted LIFE and their series was published in 1934 as “The Great Hunger.”

By 1937, Mieth was a staff photographer, and went on to publish many important assignments, including photo essays on single motherhood, yellow fever, and animal experiments. Mieth and Hagel moved in the social circles of left-wing photographers such as Imogen Cunningham, Peter Stackpole, Horace Bristol, Edward Weston, and Carl Mydans, who were members of the f-64 group or worked for the Farm Security Administration. They were intent on protesting social inequalities, war, and environmental crises. Their politics were at odds with the staunchly conservative and very controlling Luce.

One of the most interesting features of the exhibition is its inclusion of materials that illuminate the behind-the-scenes processes at LIFE, like contact sheets and editorial correspondence. For instance, in Mieth’s reportage on garment union workers, we see that images of the workers’ strike did not make the cut for publication. Neither did several images of women at work, many of them black. The published photographs—of women riding a bike and lighthearted images of the union’s summer resort, with couples boating on the lake or lounging on the ground—have an overall optimistic tone, emphasizing the American Dream and the good life, and distorting Mieth’s intent.

Though Mieth was assured the magazine was looking for photographers with different points of view, she often battled to publish the stories of social injustice that she was drawn to. Mieth’s astounding photographic essay on the internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry at the Heart Mountain, Wyoming camp in 1943 was never published by LIFE and did not become known until 1995, when the images were exhibited at Santa Clara College’s De Saisset Museum. When Mieth and Nagel refused to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, they were blacklisted by LIFE and other magazines, and this marked the end of their careers.

Marie Hansen joined LIFE as a researcher, then in 1942 became the third female staff photographer hired by the magazine along with Bourke-White and Mieth. For LIFE, Hansen documented the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, founded in May 1942, in which more than 150,000 American women served during World War II. Though the tone of the article alternated between complimentary and condescending—describing the head of the corps, Oveta Culp Hobby, as a “a svelte and definite Texas lady”—a double-page spread shows Hansen’s strong portraits of WACs.

Advertisement

Born in Germany, Lisa Larsen moved to the United States as a teenager, as Mieth had done. She started out as a picture file clerk at the photo agency Black Star, but soon became a freelance photographer for many publications, including Vogue, The New York Times, Glamour, and LIFE, where she was on staff for most of the 1950s. She was first assigned mainly entertainment and fashion stories, but soon began international reporting, most probably assigned because she was fluent in French, English, and German, and spoke some Danish and Russian as well.

In 1957, she was in Poland reporting after the riots of 1956, an uprising of industrial workers that caused a crisis among the Communist leadership and in the Soviet bloc, and on the displaced Hungarian refugees’ plight at camps in Yugoslavia, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. At the height of the cold war, she was sent to Russia. The Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev developed such admiration for her and her work ethic that he gave her a bouquet of peonies, and, during one of his anti-Western speeches, she inspired an aside from him: “Don’t misunderstand me: there is an American girl standing in front of me. Americans are good people.”

Despite its many interesting and informative anecdotes and histories, the exhibition leaves us with unanswered questions about the criteria that its curatorial team used to select these six women’s work. Many important projects from the Time-LIFE archives are missing in this one-room survey: for instance, Esther Bubley’s reportages on Albert Einstein, Marianne Moore, or Benny Goodman; Berenice Abbott’s extraordinary photo-essay “A Woman Photographs the Face of a Changing City” (1938); Dorothea Lange’s reportage on “Irish Country People” (1955) or her collaboration with Ansel Adams (“Three Mormons Towns,” 1954); Eve Arnold’s exceptional photo-essay “Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam” (1961); and Dickey Chappelle and Catherine Leroy’s extraordinary coverage of the Vietnam war, including Leroy’s own story, shot while she was captured by the North Vietnamese Army during the Tet offensive (1968).

The merit of this teaser exhibition is to make us wish for more, for deeper scholarship that would give women their rightful place not only in the history of LIFE magazine, but also, more broadly, in the field of photojournalism. Next year, an exhibition and accompanying catalog at Princeton University’s art museum will take LIFE more generally as its subject—providing at least a potential opportunity to showcase the women who contributed to its heyday. As the current New York Historical Society show’s curator Marilyn Kushner said in a recent interview, “This is just the tip of the iceberg.”

“LIFE: Six Women Photographers” is on view at New York Historical Society through October 6.