The first recorded African-American theater troupe, the African Company, was founded in New York City in 1821, a company that the white theater establishment was determined to crush. A contemporary report describes the police shutting down a performance, hustling the actors off to jail, “whereupon they were released by the magistrate only after they pledged never again to act Shakespeare.”

The works of Shakespeare were a contested possession in the United States, often used by white America to reassure itself of the country’s Anglo-Saxonness, assuaging its fear of being a creole nation, a mulatto people. In 1835, for example, former President John Quincy Adams wrote: “the great moral lesson of the tragedy of ‘Othello’ is, that black and white blood cannot be intermingled in marriage without a gross outrage upon the Law of Nature.” Nearly a century later, in 1932, his descendant Joseph Quincy Adams, the first director of the Folger Shakespeare Library, remarked in his inaugural address, “Shakespeare and America,” that Shakespeare’s works functioned, as they had during previous challenges, “during the period of foreign immigration, when the ethnic texture of our people was seriously altered,” to maintain the United States “in bonds of a common Anglo-Saxon culture.”

In the nineteenth century, Othello was a role played by white men, with only rare exceptions. An African-American actor named Ira Aldridge, who had made his debut with the African Company, emigrated to England in 1824 as the backstage assistant to an English actor. There, he not only practiced his craft, but won lasting acclaim and recognition as one of the great Shakespearean actors of the period, celebrated throughout Europe as the first black actor to play Othello, along with other leading roles in Shakespeare he couldn’t dream of playing in the United States. You can see one of the many portraits painted of Aldridge as Othello in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. He is described as having changed the very declamatory style—stylized and operatic—in which Othello had been played. Aldridge seemed to live the character rather than perform him.

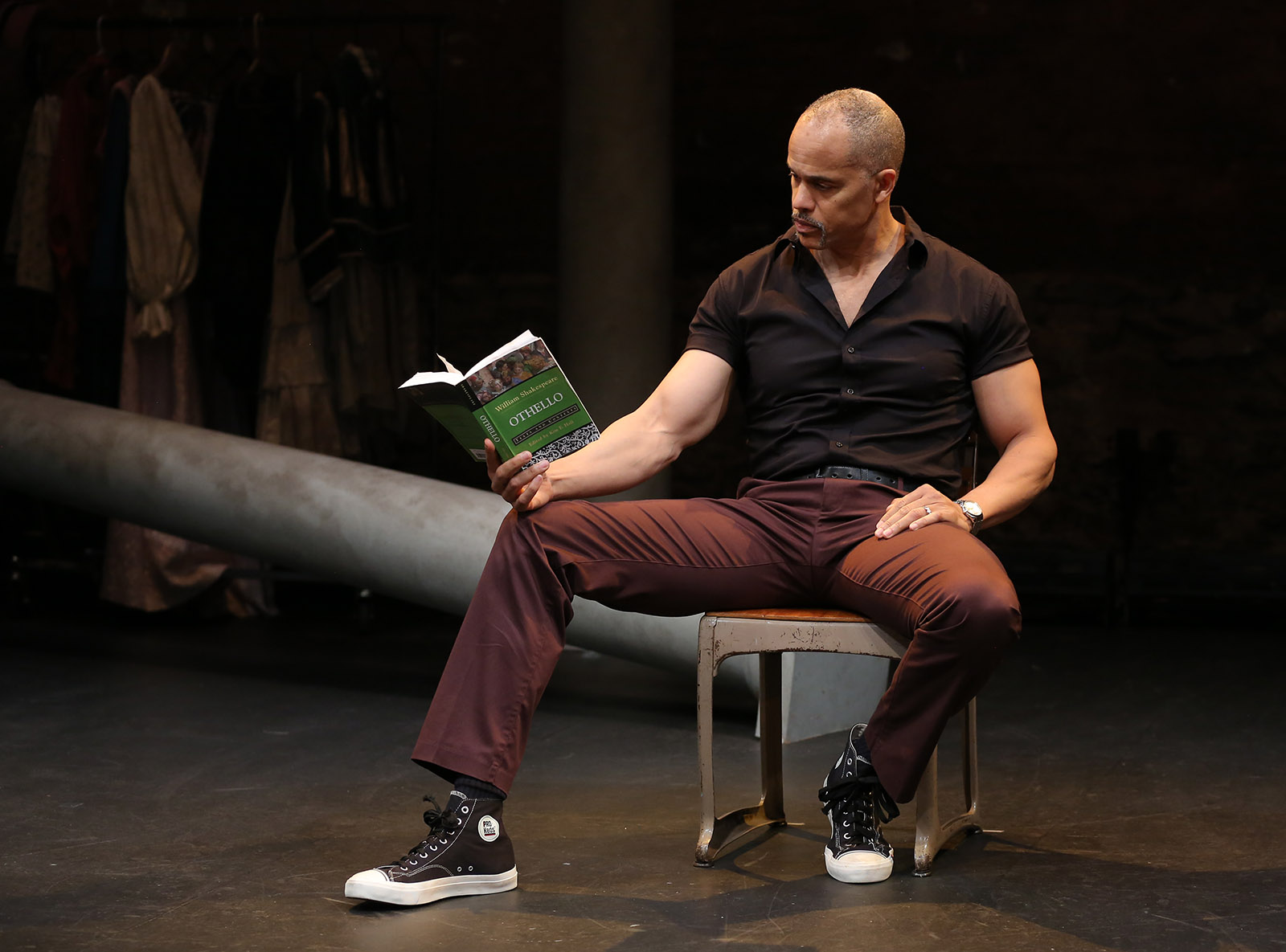

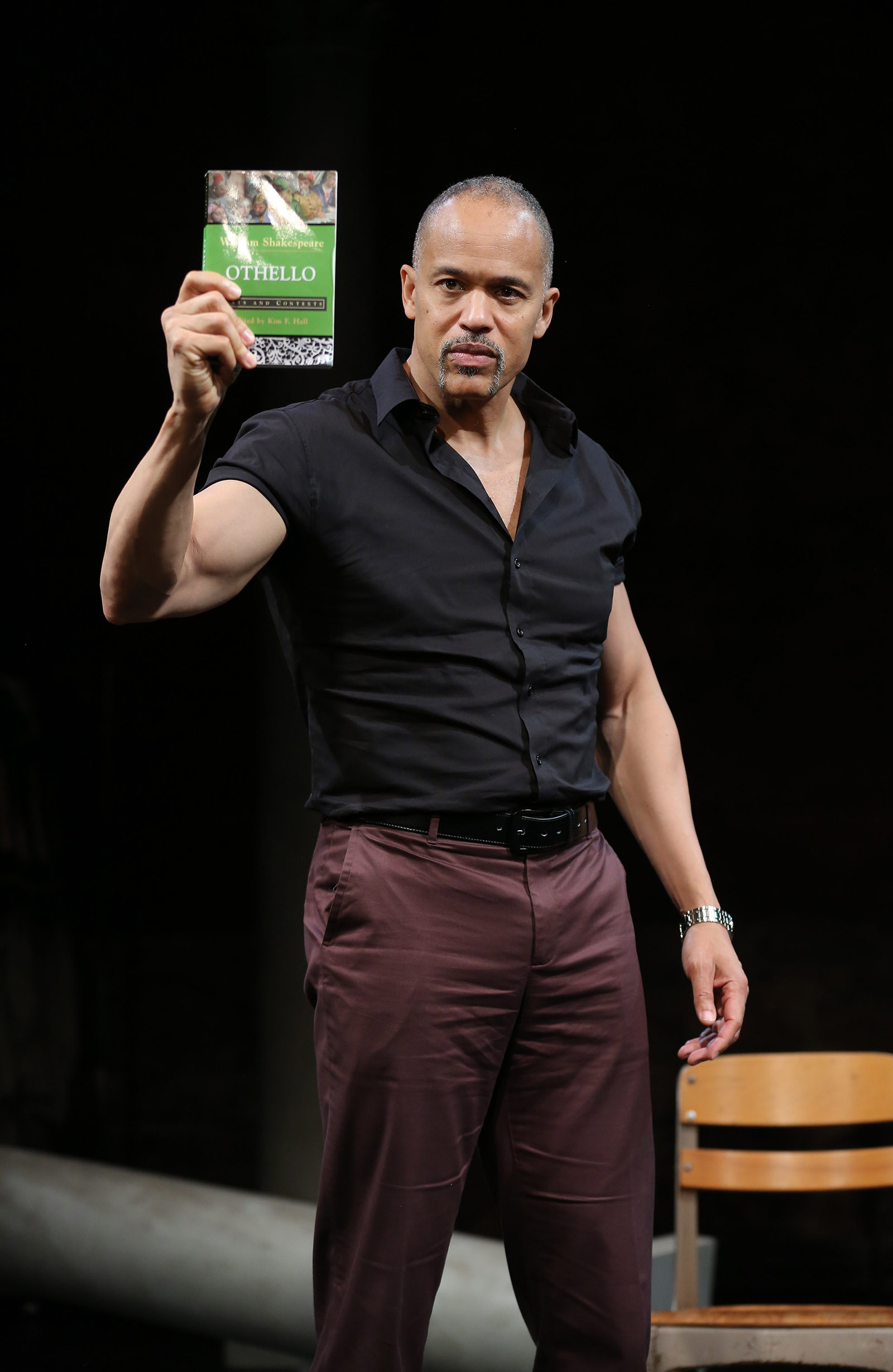

American Moor, at the Cherry Lane Theatre, is a witty, passionate, furious, and movingly intimate record of an African-American actor’s often unrequited love for Shakespeare, written by and starring Keith Hamilton Cobb, in an incandescent ninety minutes of holding the stage solo. The play takes the form of the black actor’s audition for a white director casting the part of Othello in his new production. As the audition proceeds, the performance becomes by turns a working actor’s autobiography, an exploration of America’s relationship to Shakespeare, a performance of a radically reconceived Othello, and as clear-eyed an account of an African-American man’s experience of the United States as James Baldwin’s.

The audition becomes an increasingly impossible struggle with the Director, who wants to stage a white man’s Othello, the general as an obsequious servant of the Venetian senate and a case-history of uncontrollable jealousy and irrational violence. The Actor is forced into the position of striving for a role he cannot bear to play. He needs the job.

In the opening scene, Cobb enters a set littered with theatrical paraphernalia, a jumble of wooden chairs and ladders leaning against a brick wall, lighting cables on the floor, an overturned Corinthian column, and an upright column with the Venetian Lion of St. Mark standing on top: a theater’s backstage—its unconscious, in effect, revealed in the décor. Much of American Moor is concerned with what is expressed but unheard, the riposte that is imagined but never uttered, of present unexorcized ghosts. The entrance of a black actor wearing clothes fitted to exhibit his physical splendor, as the audition and the role oblige, silently yet inevitably evokes the shadow of the slave auction, of black bodies judged, sold, and used.

From the outset, the play becomes a demonstration of an actor’s repertoire of skills—mime, richly realized verse-speaking, athletic use of the stage, even a moment of minstrel dance, contemptuously flung at the Director. Cobb enters, acting without words, narrating mostly through gesture and movement. He stretches, does breathing exercises, warms up, frequently massages his right shoulder, with a suggestion that this epically muscled body—like Othello’s—may be beginning to break down. And he repeatedly looks at his watch, as he waits for the Director to arrive.

The Director has complete power over the actor’s time. While we are waiting for the Director to appear, the Actor speaks directly to the audience about his discovery of Shakespeare as a young actor. As a black actor, he is used to being rendered invisible, when even the whole of his humanity, mustered for his performances, is deemed inadequate for the roles he craves. His solution, now, is to make the audience visible: visible at last to itself.

Advertisement

The actor’s reminiscence of negotiating a Shakespeare monologue with an acting teacher is a microcosm of his career. The actor proposes as his first choice a speech of Titania’s, and is refused. He then offers, again and again, shimmering fragments of monologues of roles denied him. For a moment he is Titania, then by turns Romeo and Juliet, weaving their speeches with his own internal monologues in a black English of jazz-like improvised syntax and sparkling profanity that he makes you hear as Shakespearean in its impassioned rhythms, verbal fireworks, and depth of feeling.

“Pick something you might realistically play!” the teacher orders him. “O, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!” the actor begins, from one of Hamlet’s soliloquies. “Hamlet is hardly your experience…” the teacher discourages him, guiding him toward the inevitable three Moorish roles traditionally considered appropriate for black actors. (The teacher doesn’t mention a fourth, the Egyptian Queen Cleopatra, still rarely played by actors of color—though, recalling Mark Rylance’s virtuoso Olivia in Twelfth Night, Cobb might make a spectacular Cleopatra.)

All the while, as the remembered teacher is refusing to consider Cobb for the lead roles reserved for whites, Cobb is, of course, performing a white person: his complexion doesn’t mysteriously segregate him from creating an acutely observed and finished portrait of the teacher’s white speech and mannerisms. It is a skill he has been obliged to learn, an actor twice over: both by vocation and as an American black man burdened with what W.E.B. Du Bois called “double consciousness,” obliged to act out conflicting roles every moment of his life. What he can’t be in Shakespeare is the measure of all he can’t be in America, even though we will see more of his perfect fluency in playing both black and white as the piece develops.

One of the pleasures of American Moor is its portrayal of how an actor builds a character, and we come to see that a character is not only himself but also an anthology of all his relationships. To play the black warrior Othello, you have to also be able to play Desdemona, to imagine what it would be to see yourself through the adamant, principled tenderness that makes her the counterpart of Iago, as implacable in love as he is in hatred. Cobb shows us both.

When the Director at last begins to speak, we don’t see him. He is tellingly sitting in the audience, his voice a disembodied, persistent, mosquito-like whine—wonderfully created by Josh Tyson. His unseen but domineering presence reveals how much the audience is itself a character in any play, bringing the gravitational force of what it wants to see, and also of what it refuses to see, to the story onstage. (A number of African-American playwrights—among them, Jackie Sibblies Drury in her Pulitzer Prize-winning Fairview—choose to engage with the audience as an integral part of the drama.) The audition evolves into a struggle between the Actor and the Director for the soul of Othello, Shakespeare’s tragedy being played out within the audition, a lived reality: “And you think you’re not in this play?” the Actor says to the Director, as their collision becomes a matter of life and death for him.

And yet, there is something heartening about this battle. We don’t go to tragedies to celebrate a foregone destruction, but to imagine, too, how the suffering might be stopped. Cobb’s Othello gives us a chance to imagine what might happen if Othello refused to take Iago’s direction. In a way, he is extending to the Director an invitation to become Desdemona, to hear the tale of all he, the Actor, has lived. “I have so much to say to you,” he says, offering that pent-up gift of his self.

Trapped in a role conceived for him by a director blind to him, Cobb nevertheless peoples the stage with a multitude of lives; he offers us an alternative Othello, whose capacity for a life that refuses tragedy makes him tragedy’s prey. And he gives us an alternative vision of an as yet undiscovered America, a true “brave new world that has such people in’t.”

American Moor, by Keith Hamilton Cobb, has been playing at the Cherry Lane Theatre, New York City, through October 5.