The Blake exhibition at Tate Britain, the first major exhibition in nearly twenty years, shows 300 of his prints and paintings, with manuscripts and printed books, gathered from galleries and libraries across the world. There have been other, smaller Blake shows with particular emphases, but this one sets out bravely to guide us through the whole range of his ideas, his art and his working life. A lot to see, a lot to take in. To corral this, the curators have imposed a chronological arrangement, setting Blake’s work in the context of the French Revolution, the spread of industry and the growing British empire, and devoting rooms to his patrons and his career as an engraver to show how he scraped a living until the relative freedom of his final years.

This is, of course, exactly the kind of crisp, rational, time-bound framework that Blake himself railed against so passionately. Yet, on the whole, it works well. Far from being dwarfed by the vast Tate rooms, within these controlling boxes Blake’s shining art explodes with energy, sometimes mystical, sometimes rippling with anger, sometimes leaping with delight.

The tone is set by the small print of Albion Rose (1793). Also known as Glad Day, this is the first thing we see, blazing against a rich blue wall. The slender figure balanced on a crag, arms spread wide, with wild rays of color bursting behind him, has often been adopted as an emblem of freedom, creativity, and resistance to constraint. Rightly so, as Blake was a rebel from the start. His parents, successful shopkeepers in London’s Soho district, recognized his talent and paid for drawing classes and for his apprenticeship to the engraver James Basire. When Blake entered the Royal Academy Schools in 1779, aged twenty-two, he drew diligently and, harboring ambitions to become a famous history painter, exhibited his historical, biblical, and literary drawings—several of which are shown here—at the Royal Academy in the early 1780s.

Increasingly, though, Blake rejected the academic teaching, preferring the Gothic mode of artists like Henry Fuseli and James Barry, and spurning the idealizing tenets of the Academy’s then-president, Joshua Reynolds. Years later, in 1809, Blake would annotate Reynolds’s Discourses with disdain. Where Reynolds wrote that the “disposition to abstractions, to generalising and classification, is the great glory of the human mind,” Blake responded in the margin, “To Generalize is to be an Idiot; To Particularize is the Alone Distinction of Merit.”

Yet Blake’s “particulars” were not those of daily life, but of a visionary imagination. In another marginal note, he wrote, “The man who never in his mind and thoughts travel’d to heaven is no artist.” His difficulties with the Academy were related to his dislike of the rational, empirical trend of Enlightenment thought as a whole, as he made clear in his epic poem Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion:

I turn my eyes to the Schools & Universities of Europe

And there behold the Loom of Locke whose Woof rages dire

Washd by the Water-wheels of Newton. Black the cloth

In heavy wreathes folds over every Nation; cruel Works

Of many Wheels I view, wheel without wheel, with cogs tyrannic

Moving by compulsion each other: not as those in Eden: which

Wheel within Wheel in freedom revolve in harmony & peace.

In this show, Blake’s famous depiction of Newton, enclosing the world in the arc of his dividers, is included in a room devoted to twelve of his “frescoes,” as he called them, believing that his complex technique copied the method of painting on damp plaster of the great Renaissance artists. These experimental monotypes have a painterly quality, sharpened by pen and ink detail, and are slightly larger than his designs for the illuminated books. Seen on this scale, Newton has a beauty and strength lost in the countless reproductions. All the great physicist’s rippling muscles are stilled by his intense concentration, while the rock on which he sits glows with rich encrustations in the depths of the sea, the sea urchins at its base swept by an invisible wave.

The Tate curators, Martin Myrone and Amy Concannon, argue that Blake the artist has been ignored in recent years in favor of Blake the poet. Yet the two are surely indivisible. After he invented his complex process of “relief etching”—its technique still unknown—text and image flow together, each reinterpreting the other. In the prophetic books, with their mix of historical characters and beings from his own mythology, the pages speak as one, visually and verbally. The tiny pages of the Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794), Blake’s first attempt to integrate text and image, mounted here so that one can see both sides of each page are almost dreamlike in their intensity.

Advertisement

The Tate show emphasizes particular works, and it is awe-inspiring to see the evolution of the illuminated books from America: A Prophecy (1793) and his “Continental Prophecies” series, to the epic poem Milton (1804–1818) and his last book, Jerusalem (1804–1820). Blake’s radical politics first came to the fore in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790), in which Satan is the voice of imagination and desire, and Eternal Delight defies the shackles of Reason. But the illuminated books could never be produced in enough numbers to make a profit, and by 1790 Blake was making his living as an engraver, in particular working for the radical printer Joseph Johnson. The influence of two of Johnson’s authors can be felt in Blake’s poem Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793). One was Mary Wollstonecraft, whose Original Stories he illustrated in 1796, and whose anger in Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) echoes in the tirade against sexual oppression delivered by Blake’s heroine Oothoon. The second was the denunciation of slavery in John Gabriel Stedman’s Narrative (1796), for which Blake was already engraving illustrations.

It is perhaps in relation to this image that the Tate has put a “Content Warning” outside the entrance, acknowledging that “The art of William Blake contains strong and sometimes challenging imagery, including some depictions of violence and suffering.” As Blake knew, though, the suffering and violence are also within us. His Ghost of a Flea (circa 1819–1820), harked back to a vision he’d had nearly thirty years earlier of a foul apparition rushing at him in his home, which filled him with terror. When he painted his ghost, he made it tiny, with scaly green and gold skin, an acorn cup in its hand to hold blood, and its tongue flickering out of its mouth. The specter was, he said, the soul of a murderer trapped in a tiny body, yet although its power was diminished it still remained ferociously menacing.

The Tate exhibition’s biographical slant sometimes genuinely deepens our understanding of Blake, as in the stress on the part played by his wife, Catherine, in printing and coloring the texts and images, including the vibrant illustrations to Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. (In 1996 the series was de-accessioned by its then home, the Frick, because of Catherine’s involvement, and now, sequestered in a private collection, it is rarely seen—but it’s among my personal favorites of Blake’s works.)

The biographical approach works less well, visually, in the spaces allotted to Blake’s friendships and quarrels with patrons (in a crowded show, the room dedicated to his sponsors William Hayley and the Countess of Egremont were virtually empty on my visits, as viewers flitted through, giving this section only a quick glance). We meet Blake next in a different guise, winning acclaim for his 1808 designs for Robert Blair’s The Grave (shown here with his drawings set alongside Schiavonetti’s engravings in four fine editions). But he still felt undervalued as an artist. Disgruntled that he had not been asked to engrave the Blair designs himself, and raging at the Royal Academy’s poor display of his watercolors, in May 1809 he defiantly organized his own exhibition above his brother’s shop at their Soho family home, 28 Broad Street.

Ten years ago, in 2009, in a small display (also curated by Martin Myrone), the Tate reunited nine of the original sixteen paintings of this exhibition. This time they have chosen to reconstruct the room itself, with its bare floorboards and pale light through the windows. It’s now a common curatorial stroke to evoke a place, to set artists “in their time”: in 2015, in a fascinating exhibition concentrating on Blake’s technical craft, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford recreated Blake’s cramped London studio in Lambeth. But there, as here, I found the effect oddly blank, like a stage-set without an actor, lacking the intensity and messiness of Blake’s life. At the Tate, another problem is that the central paintings—The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth (circa 1805) and The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan (circa 1805–1809)—hardly show Blake at his most inspired. Painted at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, they supposedly glorified Britain’s leaders, yet the portrayal of a haloed, gowned Pitt and a near-naked Nelson, posed surrounded by biblical monsters, seemed to many more like satire than tribute. Blake, however, saw these works as inspirational public art. And at the Tate, we can see the wild reach of his ambition through the use of huge screens, where slow-moving projections trace the details of digitally enlarged versions, illustrating his dream of a national commission for murals a hundred feet high.

Advertisement

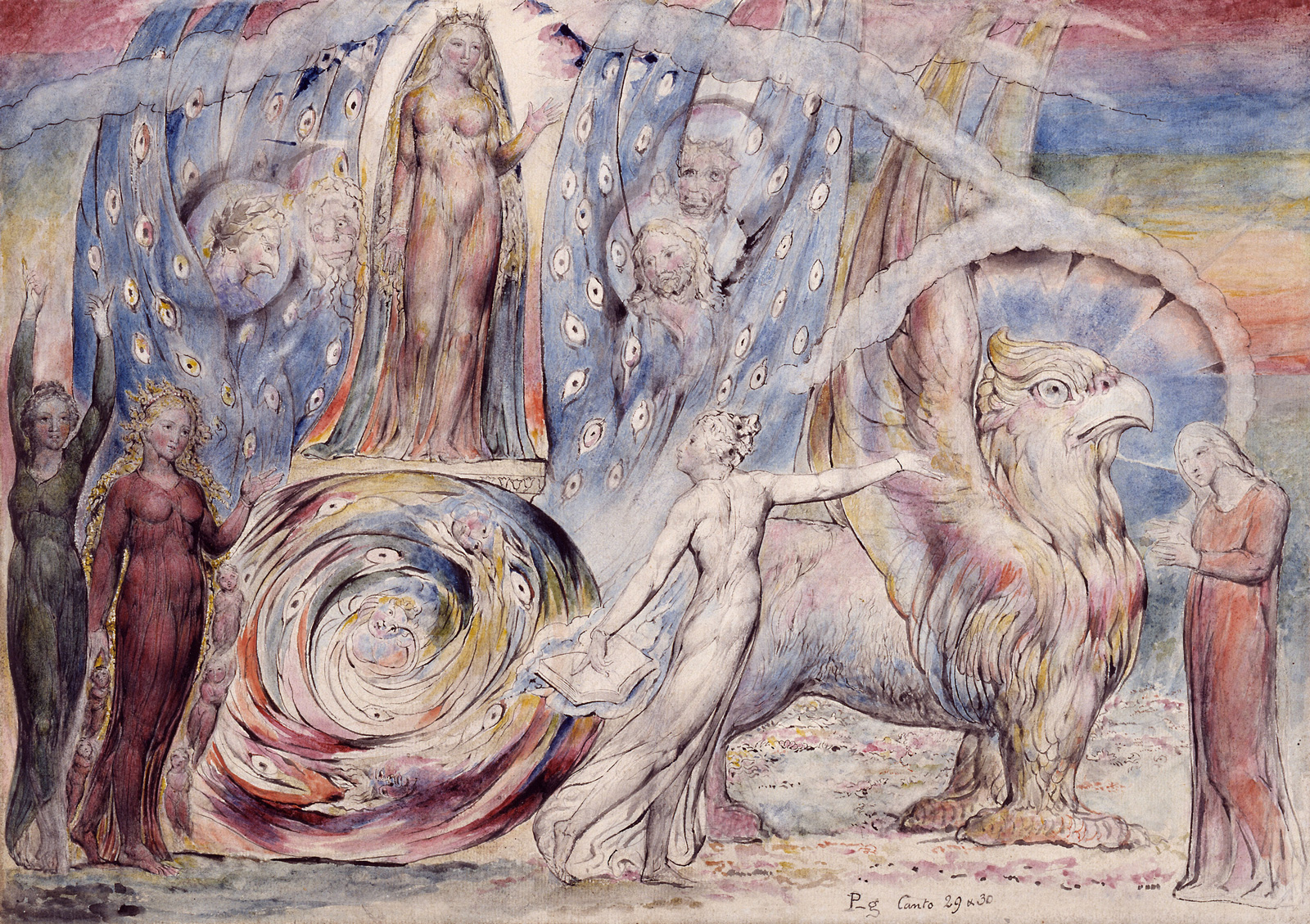

There were no sales from that 1809 show, and in the sole review, in the Examiner, the journalist Robert Hunt called the artist “an unfortunate lunatic,” whose works had been hailed as “sallies of genius” only by deluded supporters. Today, we recognize that genius. In the later rooms, the Tate pays tribute to the soaring creativity of Blake’s last decade, when he was in his sixties. At last, Blake could work with real freedom, supported by the artist John Linnell and the younger group including Samuel Palmer and John Varley, the first artistic “brotherhood” in England, known as “The Ancients” for their interest in archaism and their idealized vision of the past. Among these young friends, in addition to making sumptuous new editions of the illustrated books, and producing lyrical woodcuts for Virgil’s Georgics (1821) and powerful engravings of The Book of Job (1826), Blake painted the glorious watercolors to illustrate an edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy. With their sculptural forms and sweeping washes, these carry us to Blake’s own imagined Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise, swimming with color and light.

In these years, too, Blake finally completed his Jerusalem, produced between 1804 and 1820, charting the fall of Albion, and indeed all “enlightened” civilization. In the final room, the book’s pages, laid out in a long glass case, lead the Tate visitors back to the outside world. But the last work we see, by the door, is an impression of The Ancient of Days (originally the 1794 frontispiece for Europe) that Blake was coloring just before his death in 1827. This bearded proto-Newton measuring the universe is the fiery, crouching opposite of the dancing youth of Albion Day. Blake’s art is full of motion—verses spiral across the page, wraiths swirl and specters stoop, heroes and seekers stretch their arms high, children caper and monsters prowl, lightning crackles and flames blaze upward. Even in The Ancient of Days a wind—a breath of elemental life—sweeps the white beard and hair of the sage across the blood-red sun. Reason, Blake tells us, will always try to control imagination, but in his own glorious work there is no doubt which wins.

“William Blake” is on view at the Tate through February 2, 2020.