Hours after some of the biggest names in the pharmaceutical industry caved on the courthouse steps and agreed to pay a quarter of a billion dollars to two Ohio counties blighted by the opioid epidemic last month, a pair of emails landed in my inbox, both with a hint of menace. One came from a New York public relations firm representing one wing of the Sackler family that jointly owns Purdue Pharma and made billions from the sale of its notorious opioid painkiller, OxyContin. A D.C.-area law firm for another branch of the Sacklers sent the other.

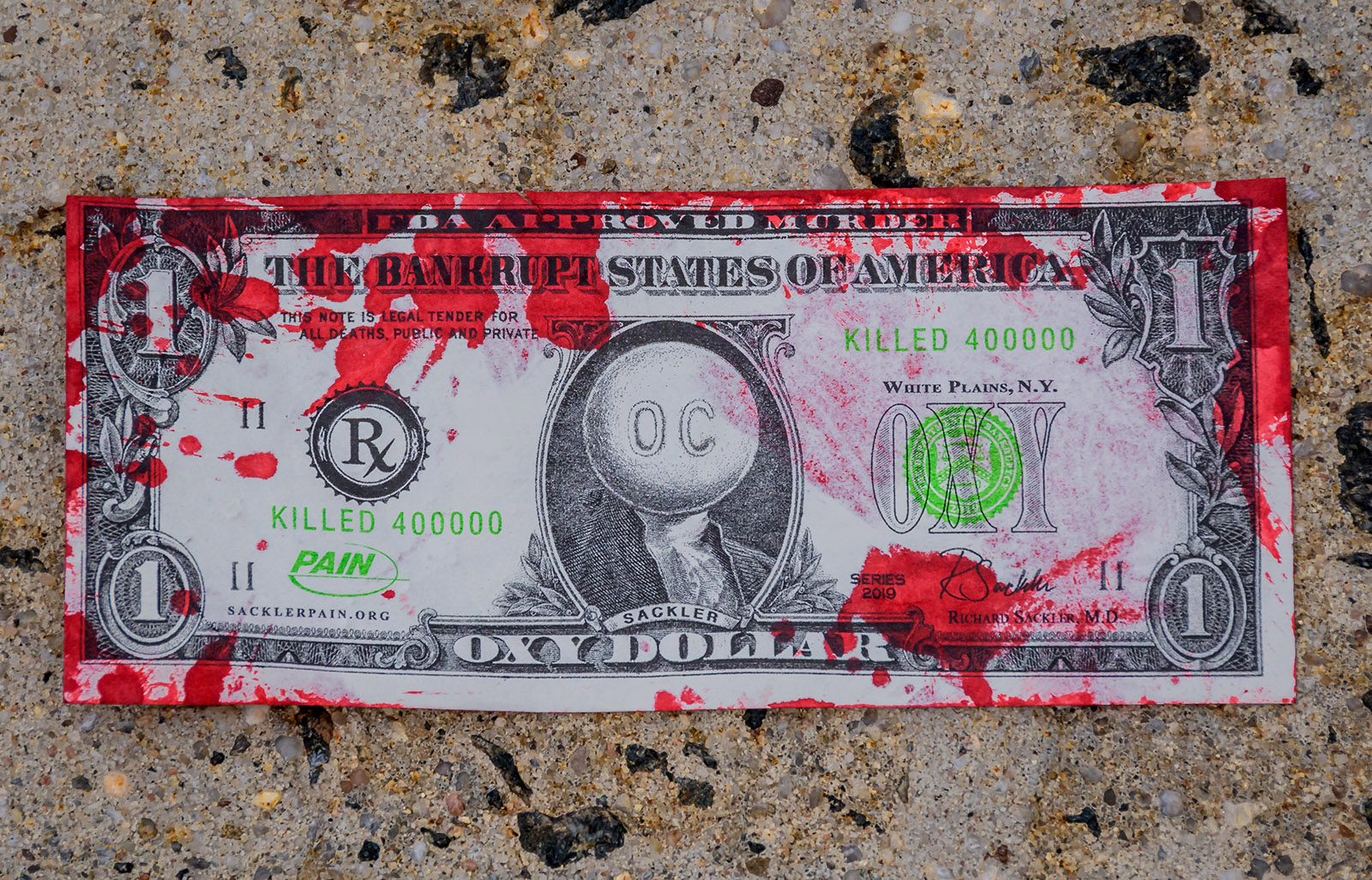

Both made the same demand: that I withdraw a claim in an article for The Guardian about the court settlement that OxyContin played a leading part in firing up an epidemic that has cost more than 400,000 lives over the past two decades. The lawyer’s letter said the statement was “false and damaging hyperbole.” The letter regurgitated manipulated statistics long pushed by Purdue’s PR strategists to claim the company’s drug was only a bit player in the crisis. Never mind that, alongside the stack of evidence of the devastation wrought by OxyContin, there is Purdue’s 2007 guilty plea to a federal criminal offense for lying in an aggressive marketing campaign that claimed the drug was less addictive and more effective than other opioids. Or that the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, formed in 2017 to advise the Trump administration, said Purdue Pharma’s unprecedented sales campaign and influence over medical policy was responsible for a tenfold increase in opioid prescribing that flooded the country with billions of narcotic pills and provided fertile ground for a surge in addiction.

Part of this is about reputation management for the Sacklers, who’ve gone from being philanthropic billionaires with their name plastered on museums, galleries, and medical institutions across several continents to pariah billionaires who are now an embarrassment to many of those who used to fete them. But there is more to it. Even as the pharmaceutical industry agrees to ever larger payouts to settle an onslaught of lawsuits over the opioid epidemic, it continues to deny the conspiracy of greed that caused what the Trump commission called “this national nightmare.” Instead, its PR operations and lawyers use manipulated statistics and make claims that the epidemic is “a complex problem with root causes that are difficult to disentangle” in an attempt to disperse responsibility so widely that, in the end, everyone is to blame and so no one is.

The principal author of the commission’s report, Professor Bertha Madras of Harvard Medical School, describes the drug industry “pouring massive amounts of money” into perverting medical policy and subverting regulation in order to push opioids. “Using that money they literally bought off, and I don’t use that phrase lightly, they bought off the Joint Commission (which accredits hospitals and sets medical policies), they bought off the Federation of State Medical Boards, they bought off several American pain associations,” Madras told me earlier this month. The industry wrote policy to influence medical practice, manipulated doctor training, and distorted the conduct of the very institutions that were supposed to protect Americans from unscrupulous drug companies. Pharma also effectively bought off Congress, blocking the efforts of a few of its members who recognized the epidemic early on and tried to rein in the wide prescribing of opioids for relatively minor pain and in quantities no other country dispensed. In the decade to 2016, drug makers poured close to $2.5 billion into lobbying and funding members of Congress on opioids and other issues, and the industry’s registered lobbyists on Capitol Hill far outnumber elected representatives.

By 2012, doctors in the US were writing 255 million narcotics prescriptions a year, enough to supply every American adult with twenty days of pills. That left the country awash in opioids that not only hooked some of those for whom they were prescribed but also created a huge surplus sitting in medicine cabinets of families who often had little awareness of the dangers they posed as the drugs were passed as if they were aspirin—or raided illicitly as word spread they were a good way to get high. It’s the job of Congress to oversee the federal agencies that in turn regulate the drug industry. But when the opioid makers’ money wields so much influence over policy and politicians, then it ends up back to front. The regulated control the regulators as the push for the mass prescribing of opioids escalated into the greatest drug epidemic in US history.

“I think that the vast amounts of money were used very effectively,” said Madras. “It was a national campaign. Have we learned the lessons? Absolutely not.”

Advertisement

Some lessons of what is in many ways a uniquely American tragedy have been learned. The epidemic is no longer in the shadows as the stigma around addiction has eroded. Doctors are more attuned to the risks of opioids and many are more cautious, with prescribing edging down over the past two years. Medical schools are finally requiring students to have proper training in pain management and addiction. State pharmacy boards have increasingly been warning their members about monitoring prescriptions. But the denials continue from those who created and did most to facilitate this tragedy. And its victims and their families are frustrated that the drug industry appears to be buying its way out of accountability and justice with financial settlements.

It’s not difficult to understand why local and state governments take the money on offer from the drug industry to settle claims even if a jury might make a much larger award somewhere down the road. For a start, the cash is available almost immediately, instead of requiring years of waiting for appeals to work their way through the courts at the risk of losing it all. But these deals deny the victims public exposure of the actions of drug executives profiteering from the opioid epidemic. The settlements studiously avoid any admission of wrongdoing and keep secret much of the hard evidence of Pharma’s greed, cynicism, and wrongdoing. That, in turn, hinders attempts to understand why this epidemic took hold in the first place in America, and not in other developed countries.

It’s no surprise that drug executives want to keep hidden their strategies to push opioids on America. Where the truth has come out, it is frequently shocking. In August, an Oklahoma judge found that Johnson & Johnson ran a “false and dangerous” sales campaign, lying about the addictiveness of opioids even as studies in the New England Journal of Medicine and research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention increasingly built the case that they did indeed cause addiction and death. In one company memo presented in court, a Johnson & Johnson sales rep reported that she told a doctor concerned about addiction and abuse that he should not worry because the result was “either fatal or they do not get affect [sic] they are looking for.” It was also revealed that Johnson & Johnson had hired the consulting firm McKinsey, which recommended the sales force focus on doctors already prescribing large amounts of rival OxyContin. Among a list of “opportunities” to increase sales was a proposal to “target high abuse-risk patients (eg males under 40).”

As it happens, McKinsey also advised Purdue on how to sell OxyContin. The judge found that Johnson & Johnson steered medical practice with substantial payments to ostensibly independent pain advocacy groups to promote opioids. The company worked alongside its rival Purdue to create a false narrative of an epidemic of untreated pain that drove up the prescribing of narcotics in part by manipulating and selectively quoting research.

Perhaps the most important vehicle in getting this scheme off the ground was an industry-backed but purportedly independent group, the American Pain Society, which a US Senate report later called the pawn of the drug-makers and “cheerleader for opioids.” The APS painted broad access to opioids as a human right, as it manipulated first the Veterans Administration and then the independent body that accredits the nation’s hospitals, the Joint Commission, into recognizing measurement of pain as the “fifth vital sign,” alongside blood pressure, pulse and respiration rates, and temperature, and to treat it accordingly.

In 2001, the Joint Commission issued new guidelines that obliged doctors and nurses to put pain treatment to the fore. But the commission wasn’t a neutral oversight body. It was in a financial relationship with Purdue, which wrote and distributed “educational materials” for free in return for virtually exclusive rights to, in effect, indoctrinate medical staff. The resulting training videos and manuals derided concerns about addiction and overdoses as “inaccurate and exaggerated.”

Stéphane de Sakutin/AFP via Getty Images

Nancy Goldin, photographer and founder of the Prescription Addiction Intervention Now group, playing dead in front of the central fountain in protest at the Louvre museum’s association with the Sackler family, owners of Purdue Pharma, Paris, France, July 1, 2019

In the early 2000s, Purdue funded more than 20,000 pain-related educational programs, which were regarded by some doctors as little more than a sales pitch for opioids. But for a lot of medical professionals, it was the only training they received. The Joint Commission’s regulations soon came to be viewed as a firm standard. Driven by hospital managements fearful of crossing the commission, an orthodoxy of prescribing opioids as the default treatment for pain worked its way into medical culture—even amid growing evidence that such prescribing was costing lives. Health insurance companies added to the pressure on doctors because narcotic painkillers were a relatively cheap alternative to other forms of pain treatment such as physiotherapy.

Advertisement

The Trump opioid commission found that this “set in motion a growing compulsion to detect and treat pain, especially to prescribe opioids beyond traditional boundaries of treating acute, postoperative, procedural pain and end-of-life care.” According to Madras, medical associations and schools were often too willing to accept the new narrative. “They simply swallowed the concept of pain as a fifth vital sign,” she said. “I think it’s one of the worst medical errors in in our history.” State medical boards trod the same path when they drew up new guidelines for pain treatment that sounded many of the same themes as the Joint Commission even as they, too, were taking money from opioid manufacturers.

Has this lesson been learned? Apparently not. Although the Joint Commission finally abandoned the guidelines that pushed the “fifth vital sign” last year, it continues to deny it was wrong to promote the mass-prescribing of opioids. Instead, it blames the APS and doctors, saying that, for its part, it was “unaware that the science behind their claims and the advice of experts in the field were erroneous.” The APS shut down this year in the face of an onslaught of lawsuits. Its leadership claimed the society was the victim of a witch-hunt.

Federal regulators also failed—not least, the Food and Drug Administration, which approved OxyContin for wide prescribing. The Trump commission found that “the FDA provided inadequate regulatory oversight” when it accepted Purdue’s claims for OxyContin, “even when overdose deaths mounted and when evidence for safe use in chronic care was substantially lacking.” The commission also noted that the FDA remained wedded to a narrow view of whether the drug benefitted a particular group of patients while ignoring OxyContin’s rising use among people who were becoming addicted to opioids. The agency, it said, wrongly accepted the pharmaceutical industry’s claim that opioid addiction was “very rare.”

And so the FDA continued to approve powerful opioids year after year, sometimes over the objections of its own advisory panels on opioids of doctors and specialists, who questioned why more narcotics were being unleashed into the market in the middle of an epidemic of over-prescribing, addiction, and overdose deaths. A former chair of one of those committees until earlier this year, Dr. Raeford Brown, told me that “the FDA has learned nothing.” He accused it of “a willful blindness that borders on the criminal” and of killing people. Brown, a professor of anesthesiology and pediatrics at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine, wants to see a complete moratorium on the approval on new prescription opioids.

Brown is not alone in believing that the FDA was too influenced by the industry’s cash: in a legacy of the Reagan era’s market-friendly policy of shifting the agency’s predominant source of funding to industry “user fees,” the very department of the FDA responsible for approving opioids receives 70 percent of its income from remittances that drug makers must pay to have their medicines approved from the drug-makers. Finally, in 2016, the FDA asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to chart an alternative path for prescription opioid approvals that takes into account the drugs’ broader impact on society. By then, opioids—both prescription drugs and the growing demand for heroin—had already claimed more than 350,000 lives in America.

Some former FDA commissioners have conceded that the agency was locked into too blinkered a view of its purpose, but it took years to change that. Trump’s first commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, a doctor with a background at the FDA who became a millionaire as a partner in a venture capital firm, strengthened oversight of the more popular opioids made of oxycodone and hydrocodone, such as Percocet and Vicodin, and began to put in place mechanisms to tighten the approval process for new narcotic medicines. But the agency continues to deny that its policies were overly influenced by the industry or that it had too close a working relationship with the opioid-makers.

Yet the revolving door between the agency and lucrative Big Pharma jobs churns relentlessly. Gottlieb took up a post on the board of Pfizer just months after resigning as FDA commissioner earlier this year. Within days, Senator Elizabeth Warren called on him to give up the post because “it smacks of corruption.”

Through it all, Congress failed to fulfill its most important responsibility—oversight of the regulators and the regulated—and instead fell into the insidious role of perpetuating the epidemic as Pharma’s money bought political inaction and kept the floodgates of prescribing open through the 2000s. Attempts by a handful of Congress members, such as Hal Rogers, Republican of Kentucky, to introduce obligatory doctor training on opioids and addiction, or to get the FDA to curb the use of prescription narcotics for lesser pain, ran into the might of the industry’s lobby and the front groups it funded. Burt Rosen, a vice-president of government affairs at Purdue Pharma and the company’s chief lobbyist in Washington, cofounded the Pain Care Forum, a grouping of drug firms, patient advocate organizations, and medical interests. The forum spent close to three quarters of a billion dollars over the decade to 2015 on writing laws, blocking legislation it didn’t like, and funding elected officials in Washington, D.C., and across the country to promote opioids and oppose curbs on prescribing.

The Pharma lobby largely succeeded in distracting from the real causes of the escalating death toll by creating a narrative of the good pain patient, who benefits from opioid painkillers, as opposed to the “abusers” who are to blame for their own addiction. With Pharma money flowing into their campaign chests, more than enough members of Congress were happy to push the line that the problem was the people, not the pills.

Rogers and a fellow Republican, Congresswoman Mary Bono, founded the Congressional Caucus on Prescription Drug Abuse in 2010 to generate political support for new laws. Bono was drawn into the epidemic when Chesare, her son with the singer Sonny Bono (half of the Sixties pop duo Sonny and Cher), became hooked on opioids after experimenting with drugs as a teenager. Rogers drafted legislation requiring the FDA to change the label on OxyContin to limit its use to severe pain. Purdue spent heavily to lobby against the bill, which failed to even come to a vote.

Through the 2000s, the opioid makers and the pain organizations they funded rallied support in Congress to block one initiative after another from Rogers, Bono, and their allies. These efforts included legislation to impose greater controls over some opioids. The American Medical Association mobilized against a law sponsored by Rogers and Bono, the Ryan Creedon Act (2011), requiring doctors to be trained to prescribe opioids. Some members of Congress were little better than spokespeople for the drug industry, repeating talking points and attacking critics. G.K. Butterfield, a North Carolina Democrat, enthusiastically praised drug distributors for their “very impressive” efforts to prevent opioids ending up in the wrong hands—even as those same companies were paying the Justice Department huge sums to avoid prosecution for failing to follow the law and report suspicious deliveries of millions of pills to tiny rural pharmacies at the heart of the epidemic.

Bono praised some of the recent legislation passed by Congress to alleviate the impact of the epidemic, but she is concerned that lawmakers have not drawn deeper conclusions about the role of lobbying in their own failure to properly oversee Pharma. “The good news is there’s nobody in denial any longer about the problem,” she told me. “But without very involved congressional oversight, it’s going to happen again.” Members of Congress, she said, need to ask themselves “really tough questions” about what went wrong, because lives were still at stake.

“They need to keep up the oversight of all the agencies to make sure they’re doing their jobs,” she went on, “Instead, there was complicity. We still have a really long way to go. People have pointed out the failures in our institutions but I don’t know that anybody’s yet addressed them.”

Far from it. As deaths—first from heroin and then from fentanyl—escalated, the opioid makers have been working to craft a new narrative. Last year, as increased caution about prescribing took hold, total opioid deaths fell slightly—though rates were still about seven times higher than they had been in 1990. More than half of those deaths, about 31,000, were from fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid. Of the remainder, heroin claimed fractionally more lives than prescription narcotics. As Pharma contrives to absolve itself, it is presenting those numbers as evidence that this is now an epidemic not of prescription medicines but of illegal street drugs.

Thus the instigators of this crisis have unhitched one from the other—as though there was no connection between the rise of prescription drugs that became widely known as “heroin in a pill” and heroin itself. And after years of showing utter indifference to the lives they blighted in the pursuit of profit, they are now arguing that to rake over the past and apportion blame detracts from saving the victims of addiction—a cause to which they see themselves generously contributing through no-fault legal settlements. No one should be fooled.