This essay is an adaptation of the fourth annual Philip Roth Lecture, delivered at the Newark Public Library on November 4, 2019. The lecture began with an appreciation of Roth’s merging of fiction and history. An admirer of great historical writing, Roth understood that, to be truly great, it had to grapple with what he called, in The Plot Against America, “the relentless unfolding of the unforeseen.” Flipped on its head, he wrote, “the relentless unforeseen was what we schoolchildren studied as ‘History,’ harmless history, where everything unexpected in its own time is chronicled on the page as inevitable.” The task of intelligibly describing the past, let alone interpreting it, risks slighting how unexpected and largely unintelligible the past was to those who made it. As Roth put it in the mind of the novel’s young protagonist, named Philip Roth, “the terror of the unforeseen is what the science of history hides, turning a disaster into an epic.” He might have added, turning triumph into an epic as well. That insight cuts to the heart of our most difficult and enduring historical issues, including the lecture’s main topic, the centrality of slavery to American history.

—Sean Wilentz

Although they diverge sharply, the most common accounts of American slavery have an air of inevitability about them. This is especially true regarding the abolition of slavery in 1865. Whether celebrated as a monument to freedom or diminished as a transition from one form of racial oppression to another, the course of Emancipation can seem almost preordained, the product of essential features of American life. If anything, we wonder why it didn’t happen sooner, and condemn past generations for their hypocrisy, mendacity, and cruelty. Yet few things if any in modern history were more unexpected than the eradication of human bondage in the Atlantic world.

A fixture and force in Western culture, time out of mind, slavery, and more specifically racial slavery, had been essential to the European settlement of the New World ever since the Portuguese pioneered the plantation system with enslaved African labor in the sixteenth century. Apart from sporadic protests, the spread of slavery went virtually unchallenged by European and British settlers let alone their governments; periodic slave revolts and insurrectionary plots did not appreciably slow the rise of the plantation complex that at its height stretched from Brazil to the Caribbean to British North America. There is evidence inside the Anglo-American world, dating back to the seventeenth century, of popular repugnance at slavery and, especially, at the brutal Atlantic slave trade, but that sentiment slumbered for many decades, sufficient to raise moral doubts but too feeble to produce political action.

Suddenly, in the late 1740s and early 1750s, Western culture reached a turning point, producing what the great modern scholar of slavery and the antislavery movement David Brion Davis called “an almost explosive consciousness of man’s freedom to shape the world in accordance with his own will and reason.” The causes of this moral revolution were manifold and remain much debated, but need not detain us here; what is important is that it brought, in Davis’s words, “a heightened concern for discovering laws and principles that would enable human society to be something more than an endless contest of greed and power.” That concern made slavery appear for the first time—to the un-enslaved—as a barbaric offense to God, reason, and natural rights.

Rejecting the dogmas of the past meant scrutinizing inequality, personal sovereignty, national sovereignty, and servitude of every kind. In France, Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws destroyed ancient justifications for slavery, which inspired and emboldened antislavery religious sectarians and budding philosophes across the Atlantic world. In Philadelphia, the pioneering Quaker abolitionist John Woolman, a major figure in the antislavery awakening, published his first antislavery tract in 1754. A few years later, his friend and fellow Quaker Anthony Benezet began recruiting a network of intellectuals and political leaders to the cause. By the mid-1770s, in the American colonies as well as in Britain and France, a significant number of reformers and intellectuals had come to regard American slavery as pure evil. Over the next fifteen years, they set in motion political movements dedicated to eradicating the degradation of persons into property.

Against slavery’s millennia, the struggle to abolish it came abruptly. By the end of the succeeding century, against slavery’s immense and unyielding power, it had largely succeeded. As a spiritual as well as political endeavor, it is one of the most, if not the most astonishing unfolding of the unforeseen in all of recorded human history. Yet it is too often at best consigned to the inevitable, as something that was bound to happen as if in the natural unfolding of progress. At worst, it is pushed to the margins, as if slavery’s abolition came about without abolitionists, without politics, let alone without rebellious slaves—the byproduct, as some accounts say, of impersonal, amoral economic forces, or the unintended outcome of white people’s selfish squabbles over policy and profits, or even as an accident.

Advertisement

The neglect of historical understanding of the antislavery impulse, especially in its early decades, alters how we view not just our nation’s history but the nation itself. More and more in these pessimistic times, we are learning once again, and with a sense of justice, that the United States and its past are rooted in vicious racial slavery and the lasting inequities that are slavery’s legacy. We learn too little or not at all that the United States and its past are also rooted in the struggle against slavery, and in the larger revolutionary transformation of moral perception that produced that struggle—a transformation that, with all of the contradictions, helped give the New World its symbolic meaning of rebirth.

Effacing this essential tension—that the United States was defined, from the start, neither by American slavery alone nor by American antislavery but in their conflict—can lead to a strange complacency. Because the ideals that propelled the American Revolution shared crucial origins with the ideals that propelled antislavery, it can be tempting to treat slavery as a terrible appendage to American history, an important but also doomed institution at the nation’s founding.

The historian Bernard Bailyn has offered one influential version of this view in his description of how the Revolution unleashed a “contagion of liberty.” Slavery, although a central part of American society, hardly encapsulated the ideals of the Declaration of Independence; it contradicted them, for reasons later explained by no less of an authority than Abraham Lincoln. The American Revolution may not have overthrown the institution of slavery but its egalitarian principles were at least implicitly antislavery. The anomaly became more glaring over the succeeding two generations when, in yet another unfolding of the unforeseen, American slavery did not die out as most expected but expanded, turning the American South into the most dynamic and ambitious slavery regime in the world. Still, when Emancipation arrived, it did so as a vindication and affirmation of America’s founding principles, the “new birth of freedom” that Lincoln pronounced at Gettysburg in 1863. It confounded the claims of those reactionary pro-slavery apologists who belittled Thomas Jefferson as a cunning dissembler and who regarded the Declaration’s assertion of self-evident equality as, in the words of one Indiana senator from 1854, “nothing more than a self-evident lie.”

One problem with this familiar view is that it obscures how new, how radical, antislavery politics were during the revolutionary era, and how, for many patriots, American slavery and American freedom were perfectly compatible. I’m referring here not to those slaveholders with troubled consciences like Jefferson and James Madison, Virginians who perceived slavery as an intolerable offense yet who (at least after the 1780s, in Jefferson’s case) lifted not a finger toward ending it—critics of slavery who continued owning, buying, and selling human beings until the day they died. I’m referring instead to stridently proslavery figures like that young South Carolina grandee and signer of the Constitution, Charles Pinckney—a patriot who served as an officer in the revolutionary militia and who, as a delegate at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, asserted “if slavery be wrong, it is justified by the example of all the world.” I am also referring to those white Northerners, as well as most white Southerners, who believed that the Declaration’s egalitarian principles were perfectly sound but that they categorically did not apply to blacks, slave or free. Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney attempted finally to enshrine this racist egalitarianism in American national law in his notorious ruling on the Dred Scott case in 1857.

These proslavery Americans and apologists for slavery and their progeny were no less products of the American founding than the early abolitionists inspired by Woolman and Benezet or the conflicted enlightened Virginians like Jefferson. Plantation slavery grew stupendously in the United States after the Revolution, generating a well-organized slave power that long dominated national politics. Slavery’s defeat was not inevitable. Nor, obviously, did white supremacy die with slavery. Over the century and a half since slavery’s abolition, the racist Americanism of Charles Pinckney and Roger Brooke Taney has survived and flourished in new forms, along with dominating social and political structures that uphold it. Far from vanquished, it has morphed and resurged in ways expected and unexpected, from the bloody overthrow of Reconstruction to the menacing rise of Donald J. Trump.

Advertisement

There is another view that challenges the familiar one, hailed by its supporters for forcing an honest reckoning with slavery and its unending consequences. This account asks profound and unsettling questions about the nation’s origins and bids us to regard the experience of the slaves as the true test of America’s professed ideals. Slavery, in this view, wasn’t simply an important part of American society at the founding and after; it defined a nation born in oppression and bad faith. While this view acknowledges the ideals of equality proclaimed by Jefferson and others, it regards them as hollow. Even after slavery ended, the racism that justified slavery persisted, not just as an aspect of American life but at its very core.

If the familiar view courts complacency, this one is vulnerable to an easy cynicism. Once slavery’s enormity is understood, as it should be, not as a temporary flaw but as an essential fact of American history, it can make the birth of the American republic and the subsequent rise of American democracy look as nothing more than the vindication of glittering generalities about freedom and equality founded on the oppression of blacks, enslaved and free, as well as the expropriation and slaughter of Native Americans. It can resemble, ironically, the reactionary proslavery insistence that the egalitarian self-evident truths of the Declaration were self-evident lies. It can leave our understanding of American history susceptible to moralizing distortions that seem compelling simply because they defy reassuring versions of the past.

Some of that cynicism is on display in The New York Times Magazine’s recently launched 1619 Project, enough to give ammunition to hostile critics who would discredit or minimize the entire enterprise of understanding America’s history of slavery and antislavery. The project’s lead essay, for example, by Nikole Hannah-Jones berates our national mythology for “conveniently” omitting “that one of the primary reasons the colonists decided to declare their independence from Britain was because they wanted to protect the institution of slavery.” Supposedly, Britain, by 1776, “had grown deeply conflicted over its role in the barbaric institution that had reshaped the Western Hemisphere.” There were, the essay says, “growing calls” in London to abolish the slave trade, which would have “upended the economy of the colonies, in both the North and the South.” Americans, in short, “may never have revolted against Britain” had the founders not believed that independence “was required in order to ensure that slavery would continue.” The American Revolution, in effect, anticipated the slaveholders’ rebellion eighty-odd years later: the American patriots allegedly declared their independence of Britain in 1776 for the same reason that the Southern states seceded in 1860–1861, to guarantee that slavery would endure. American independence, in this view, was a precursor of Southern secession.

It is worth noting that Jefferson Davis and the rebellious slaveholders also depicted secession as a glorious replay of the American Revolution, although they did not go so far as to claim that the patriots of 1776 fought to protect slavery. Not for the first time, modern critics have concluded that the Confederates were basically correct about American history, whereas Lincoln as well as most abolitionists, above all Frederick Douglass, were wrong—as when Douglass, in his most famous speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?,” excoriated American hypocrisy and white racism but also praised the US Constitution as “a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT.”

Coincidence aside, though, this portion of the 1619 Project is simply untrue. Neither the British government nor the British people were “deeply conflicted” over slavery in 1776. To be sure, controversy did arise in the 1760s and 1770s over the legality of owning slaves on British soil proper, where wealthy merchants and gentlemen held thousands of slaves chiefly as house servants; and in 1772, a small group of abolitionists succeeded in getting Britain declared free soil in the landmark Somerset decision. But these efforts affected roughly the same number of enslaved persons as lived in the single colony of New York; more important, they affected Britain’s entrenched involvement in colonial slavery and in the slave trade not at all. Apart from the appeals of a tiny handful of abolitionists like Granville Sharp, there were no “growing calls” in London to halt the Atlantic slave trade; on the contrary, it had been American colonists who attempted to end involvement in the Atlantic slave trade only to be overruled by the Crown and its colonial officials.

Had the Americans not won their independence in 1783, it is almost inconceivable that the British government would have ended slavery in any of its colonies thereafter. Although Lower South slaveholders and their Northern allies succeeded in removing from the Declaration Jefferson’s language describing the slave trade as a “cruel War against human Nature itself, violating its most sacred Rights of Life and Liberty,” and although Jefferson blamed the introduction of slavery on the monarchy, this hardly turned the fight for independence into a fight to sustain slavery.

Cynicism about the Revolution gives way to cynicism about the Civil War and, in particular, about Abraham Lincoln—rendered as a white supremacist who, whatever his qualms about human bondage, supposedly had no interest in ending slavery, but only in preserving the Union. One is left to wonder how Lincoln’s first Inaugural Address, delivered weeks before the fighting began, affirmed to one admittedly unfriendly Northern editor “that anti-slavery is the corpus, the strength, the visible life of the party which has now assumed the reins of government.” One is bidden to forget that the war was a Southern counterrevolution against the victorious Republicans’ explicit intention to place slavery, in Lincoln’s words, “in the course of ultimate extinction”—and much else that Lincoln said against slavery—a counterrevolution that Lincoln was determined to crush. It took a year and a half—just a year and a half—before the Emancipation Proclamation officially turned the struggle against secession into a struggle for liberation under force of arms, fought in part by African-American Union troops who included more than one hundred thousand former slaves. That, too, was part of the Emancipation Proclamation. From the very start, however, the war for the Union was inherently antislavery.

The antislavery impulse, of course, has not disappeared utterly from our accounts of American slavery. Historians rarely fail to credit the radical abolitionist movement that arose in the 1830s under the leadership of, among others, William Lloyd Garrison, for courageously calling to moral account not just the slaveholders but their Northern accomplices and apologists. Hannah-Jones’s essay cites the Pennsylvania Anti-Federalist and abolitionist Samuel Bryan attacking the US Constitution in 1787, as well as the later abolitionist William Goodell.

Our current interpretations, though, fail to appreciate both the magnitude of the unforeseen antislavery rupture with the past and America’s crucial role in that rupture. They overlook how organized antislavery politics originated not in the Old World but in the rebellious British North American colonies. One line of argument finds it hard to explain how most slaveholders and some antislavery advocates reasonably regarded the nation’s founding in 1787 as a blow for slavery. The other cannot explain why leading abolitionist and antislavery voices just as reasonably believed exactly the opposite, that the Constitution advanced the promise proclaimed by an anticipatory ode published in Philadelphia: “May servitude abolish’d be / as well as negro-slavery / To make one LAND OF LIBERTY.”

*

Placing antislavery along with slavery at the center of American history produces an unfamiliar alternative history that tracks the unfolding of the unforeseen. Lacking a novelist’s genius for invention, a historian can only record it. This alternative account illuminates the fragility of history not by telling what might have happened and didn’t, as in The Plot Against America, but by relating things that did happen, disrupting all that seemed settled and foreclosed back then, as well as what might now seem settled fact about American history. Above all, it shows that Revolutionary America, far from a proslavery bulwark against the supposedly enlightened British Empire, was a hotbed of antislavery politics, arguably the hottest and most successful of its kind in the Atlantic world prior to 1783.

The history begins in the 1680s, at more or less the same time that plantation slavery was established in the Chesapeake. The year 1619 has become symbolic of slavery’s commencement in our history, when a Dutch man-of-war consigned twenty Africans and creoles to John Rolfe in Jamestown, to be sold to wealthy local planters. Only in the last quarter of the seventeenth century, however, did the slave plantation economy in tobacco take root in Virginia and Maryland, followed immediately by the spread of plantation slavery in the rice, cotton, and indigo producing low country regions to the South. Slavery and slave trading likewise took hold in all of the colonies to the North, particularly in the infant seaport cities, where as much as one-fifth of the population consisted of enslaved laborers, as well as in the proximate hinterlands.

What 1619 has become to the history of American slavery, 1688 is to the history of American antislavery, the year that four German speaking Quakers in the settlement of Germantown, Pennsylvania, raised what is generally regarded as the first written public protest against African-American slavery in the British colonies. Denouncing slavery as a violation of the Golden Rule, they initially directed their petition to the local Quaker monthly meeting, but it had no effect and was forgotten until its accidental rediscovery in 1844.

Antislavery sentiment persisted in Pennsylvania, as part of what became a dissenting tradition inside the Society of Friends aimed by a minority of pious Quakers against the more extravagant slaveholding and slave-trading majority. Finally, in the 1750s, a full-scale reformation of American Quakerism produced a revulsion against what was still very much a fundamental institution in the Quakers’ world, but the reformation did not expand much beyond the Friends. As late as 1763, only a small minority of British or European colonists anywhere in North America thought involvement in slaveholding or the slave trade, direct or indirect, deserved the slightest ethical questioning.

Yet the moral revolution of the 1740s and 1750s, advanced on these shores by prophets like John Woolman, exploded after the French and Indian War, the American front of the European Seven Years’ War, amid the rising colonial revolt against imperial rule. Couching political complaints not as assertions of customary English rights and liberties but as tests of universal principles and natural rights rapidly dishonored holding Africans and their children in permanent slavery. As the historian Christopher Leslie Brown writes:

More than a decade before the development of abolitionism in Britain, the middle and northern colonies in North America presented the unusual spectacle of societies with slaves turning against the practice of human bondage, in part, to abide by the dictates of professed values, or to liberate themselves from moral corruption.

Although that spectacle was most striking in the colonies where slavery was less uniformly central to the economy, the contradictions for a time became felt even where plantation slavery was strongest and enslaved persons the most numerous. Remarking on the period of the 1770s, the leading South Carolina politician Henry Laurens, a major slaveholder and possibly the country’s premier slave trader, recalled how he and his fellow planters became “solemnly engaged against further importations under a pretence of working by gradual steps a total abolition.” Over the succeeding decade, Low Country South Carolina planters would manumit more slaves than they had during the previous thirty years.

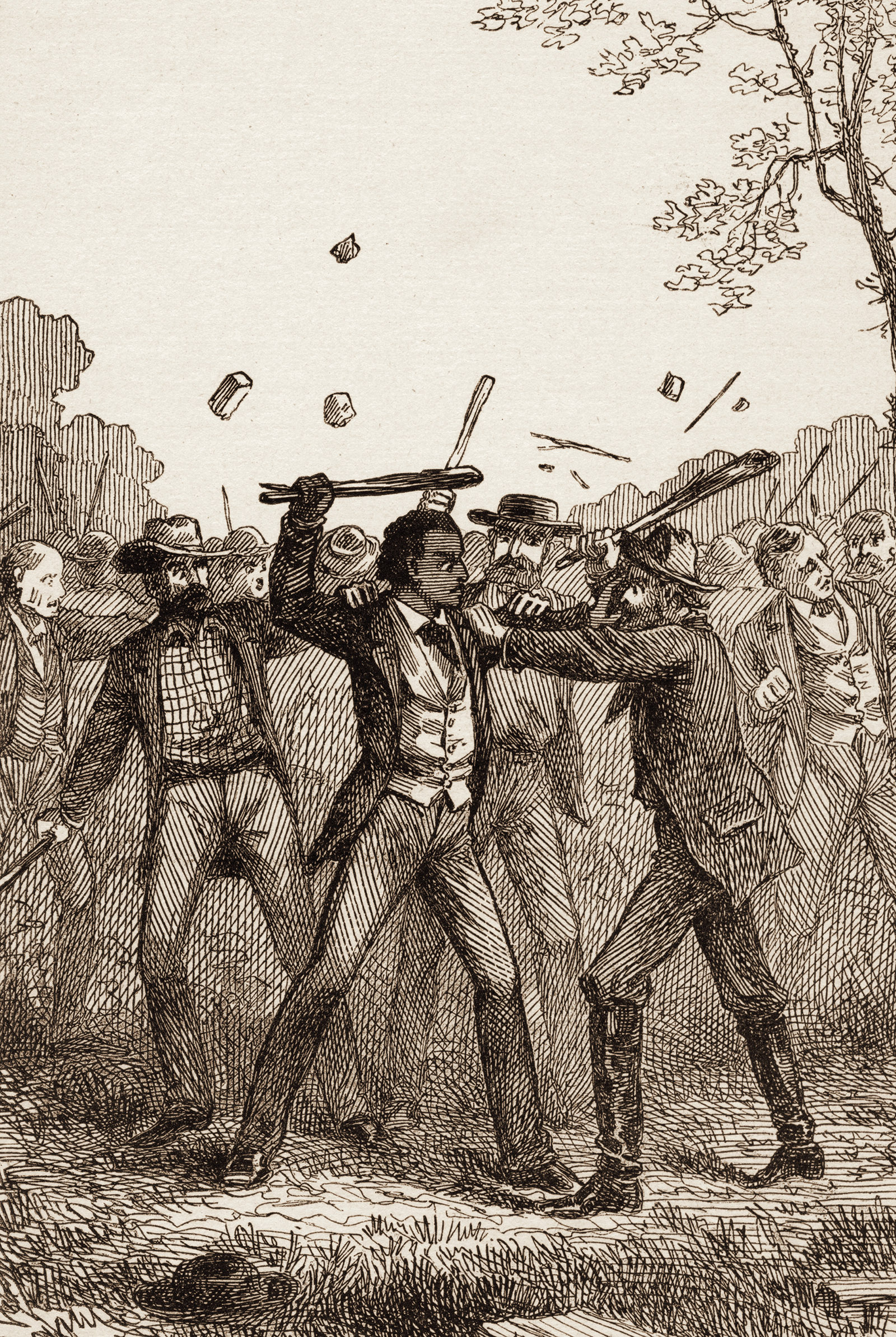

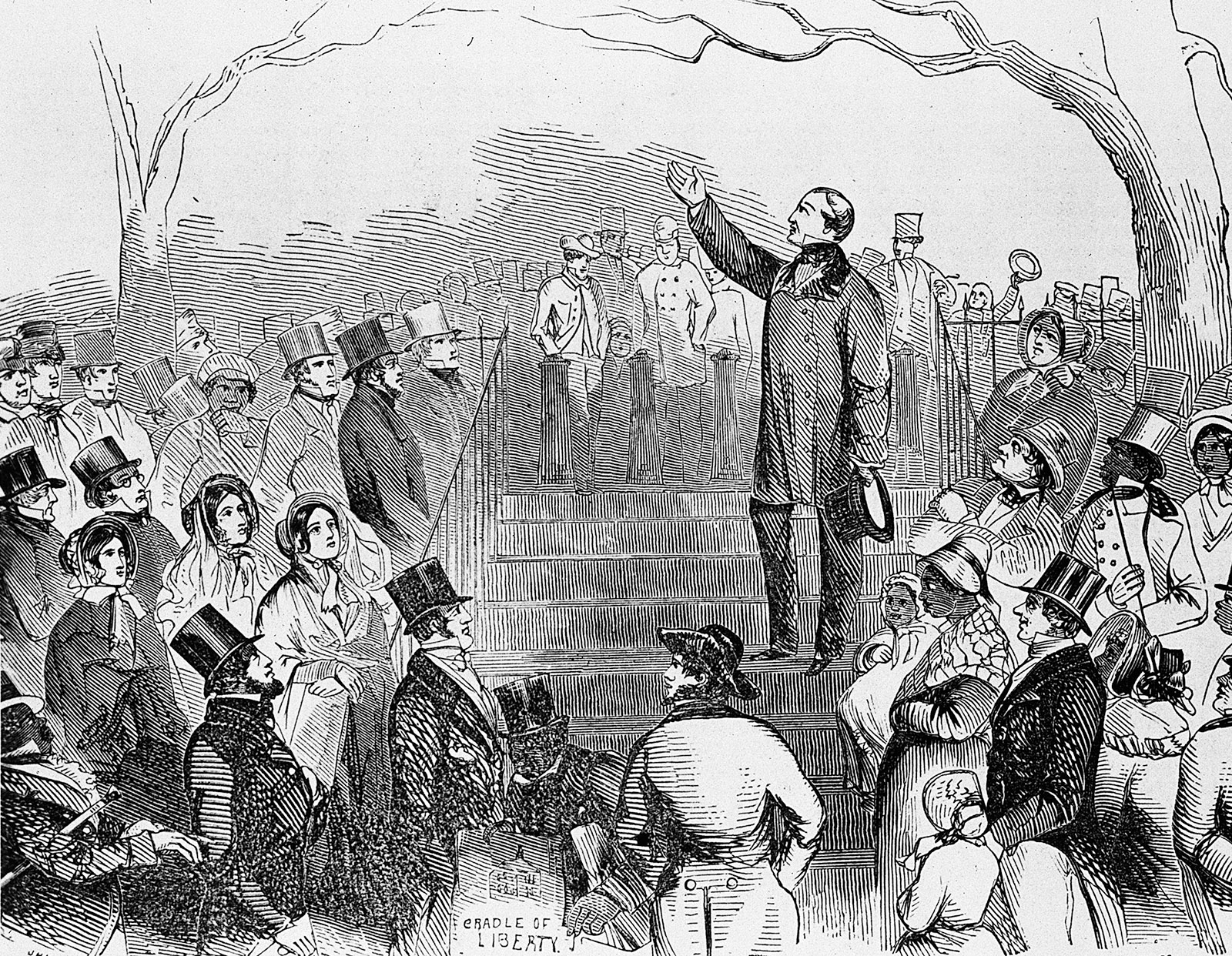

Between 1767 and 1775, a wave of antislavery petitions, sermons, pamphlets, and private missives swelled across the colonies, from New England as far south as Virginia—a political outburst unprecedented in the Atlantic world. At least half a dozen Massachusetts towns, and several others elsewhere in New England, instructed their representatives to propose antislavery legislation at the colonial assemblies. In the city of New York—home to the largest number of slaves in any American city other than Charleston, South Carolina—local distillers voted in 1774 not to distill molasses or syrup intended for the slave trade. In April 1775, five days before the battles of Lexington and Concord, a group of ten Philadelphians, seven of them Quakers, formed the first antislavery organization in history, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. Two months later, a group of local leaders met in Worcester, Massachusetts, to announce their determination to achieve the abolition of slavery.

The upsurge achieved some rapid results. In 1777, fractious Vermonters adopted the first written constitution in history to outlaw adult slavery. That same year, when drafting a new state constitution, the New York State legislature stopped short of approving emancipation but endorsed the principle that their state should be free soil and exhorted future legislatures to take the most effective and prudent steps toward “abolishing domestic slavery.” Three years later, the Pennsylvania assembly approved the first legislatively enacted emancipation law in modern history; four years after that, Rhode Island and Connecticut passed similar measures. Petitions and freedom suits initiated by slaves and pressed by antislavery legislators and lawyers undermined slavery’s legitimacy in Massachusetts, leading to the landmark rulings in cases involving the slaves Quock Walker and Mum Bett, which in 1783 outlawed slavery under the terms of the commonwealth’s constitution of 1780.

The Atlantic slave trade came in for similar attack. Between 1769 and 1774, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland either passed highly restrictive duties on slave imports or banned the imports outright. Measures abolishing the trade also won approval in Massachusetts, New York, and Delaware, only to be thwarted by royal governors. The Virginia General Assembly, calling the commerce “an inhumanity,” passed high duties on the slave trade in 1767, 1769, and 1772, rejected on each occasion by the King’s Privy Council. Finally, the Continental Congress, acting in 1774 and 1776, halted the trade until the end of the Revolutionary War.

In all, by 1787, five Northern states had either abolished slavery or put it in the course of abolition; New York, the largest slaveholding state north of Maryland, had passionately debated abolition and come close to enacting an emancipation law in 1785, finally achieved in 1799; public debates in New Jersey, which would hold out the longest, until 1804, had been roiled by talk of abolition from neighboring states. In Virginia, where the legislature liberalized manumission laws in 1782, lawmakers three years later seriously debated a gradual emancipation proposal initiated by a statewide petition campaign.

It needs emphasizing that outside of northern New England, where slavery was crumbling already, success was hard-won, even if the overall number of slaves, compared to the South, was very small. In some portions of lower New England and the Middle States, notably New York’s Hudson Valley, slavery and slave trading were important to the local economy, and resistance to antislavery efforts there was especially strong; but slaveholders everywhere ferociously fought any proposal for emancipation. The heart of the matter, for them, was property rights, an issue that won over to their side many non-slaveholders.

No state was prepared to offer direct monetary compensation for freeing the slaves (as Britain would grant its colonial slaveholders in 1833); slaveholders, who wielded outsized political power, charged that anything short of such compensation, paid in full, would be, as one proslavery New Jerseyan put it, “a solemn act of publick ROBBERY, or FRAUD.” Some slaveholders opposed even compensated emancipation, insisting that legislators had no authority whatsoever to interfere with vested property rights. Beginning in Pennsylvania, abolitionist advocates and lawmakers in most states had to settle for compromises that freed only the children of slaves and kept them in indentured servitude for a period that in some places—at the slaveholders’ insistance—ran four to seven years beyond the age of majority.

To the most fervent abolitionists, the compromises amounted to a bogus emancipation that still left slaves, as one of them put it, “groaning under the rod of a cruel unfeeling tyrant.” Most historians today appear to agree, describing Northern emancipation, with a touch of cynicism, not as the product of intense political struggle between insurgent abolitionists and politically powerful slaveholders but as a “grudging,” half-hearted enterprise that rewarded slaveholders with a kind of indirect compensation.

Their accounts relate important truths about the limitations of Northern emancipation. But they ignore how, with unprecedented force and against the immense weight of the past, abolitionists and their political allies abolished outright or initiated the abolition of an entire category of property—by any measure, a radical act in a world dedicated to the guarantee of property as a vested right. They slight how even the most gradual emancipation laws immediately broke the chattel principle regarding the children of slaves, which was a cornerstone of American slavery. They overlook how resistant slaveholders forever considered the measures repugnant and oppressive, unjustly depriving slaveholders, one Massachusetts jurist wrote, “of property formerly acquired under the protection of law.” They suppress how the legislation formally branded slaveholding, an institution almost universally deemed perfectly valid among whites less than twenty years earlier, as an abomination—one that, according to the 1780 Pennsylvania law, robbed slaves of the “common blessings” of nature while casting them into “the deepest afflictions.”

As its victories piled up, the haphazard antislavery movement began to cohere and push for still larger reforms, regarding its previous successes, according to the Pennsylvania law, as just “one more step to universal civilization.” In 1784, the Philadelphia antislavery group, having suspended operations during the Revolutionary War, reorganized as the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of the Abolition of Slavery. A year later, New Yorkers formed their own manumission society. By the end of 1790, at least six more self-styled abolitionist societies had appeared, from Rhode Island to Virginia.

These groups, restricted to white members, were not paragons of racial egalitarianism, as some historians are quick to point out. Some of the societies even admitted slaveholders to their ranks. Yet the revolutionary-era abolitionists envisaged black equality as well as black freedom in a biracial society, and they collaborated closely with African Americans, enslaved and free. The societies in time struck alliances with intrepid black abolitionists; individual members worked tirelessly with untold thousands of enslaved men, women, and children, pursuing claims of freedom with extraordinary success. Stopping short of extra-legal action, the abolitionists agitated to protect and expand the civil rights of free blacks respecting everything from access to the courts and securing marriages to preventing kidnapping into bondage. For the abolition societies, one leading New York African-American abolitionist later remarked, ending slavery was a prelude to eliminating racial distinctions and assuring that “equal justice is distributed to the black and the white.”

The American movement in turn became the antislavery beacon to the rest of the Atlantic world and especially to beleaguered British abolitionists like Granville Sharp. Having formerly berated the colonials en masse as slaveholders, Sharp would credit the American abolitionists, with whom he built close connections, for moving him to trace “the evil to its source.” His broadcasting of American antislavery and anti-slave trade tracts became the foundation for the great upsurge of British agitation against the slave trade that began in the late 1780s. For Sharp, as for other British abolitionists friendly to the patriot cause, the American Revolution loomed as the instigator of a civil war within the Empire that promised to eradicate slavery and servitude of every kind.

Sharp and the others were wrong: the American Revolution was also a slaveholders’ revolution, and in its aftermath, slaveholders stiffened their resolve to affirm their property rights in human beings. In the Lower South, where the humanitarian ripples from the 1770s died, slaveholders deemed slavery not simply as a necessity for their economic survival but as a scripturally sound and even noble institution, ratified by the example of the entire world. In Virginia, enlightened slaveholders like Jefferson faced the reality that proslavery planters ruled the roost in their own state and, in any case, that they possessed neither the strategy nor the will to pick up on the example of Northern emancipation.

When delegates assembled in Philadelphia in 1787 to design a stronger federal union, there was never a question about their granting the new national government authority over slavery in the states where it already existed. Southern slaveholding states were not about to give the new government the power to abrogate their property laws, including those enshrining slavery, any more than Northern states would surrender power over their property laws, including those advancing emancipation. Still, antislavery delegates to the Constitutional Convention, urged on by organized abolitionists outside the convention’s closed doors, aimed at the very least to insure that the government had the authority to abolish the Atlantic slave trade—to that point, the vital first step in every blueprint yet devised for ending American slavery.

Lower South slaveholders violently refused, declaring the matter non-negotiable. Either leave the slave trade untouched and in the hands of the individual states, the rebarbative South Carolinian John Rutledge announced, or the Lower South “shall not be parties to the Union.” Yet, while they managed to salvage a significant twenty-year delay, and came away with enough to tell their constituents back home that they had secured a proslavery triumph, the slaveholders lost the main issue. The Constitution conceded to the slaveholding states a measure of extra representation in Congress and the Electoral College, although it was far from determinative; and it gave them a weakly worded clause on returning their fugitive slaves. The convention majority refused, however, to acknowledge slavery’s legitimacy in national law, which gave the new national government authority over slavery wherever it exercised jurisdiction, as in the national territories. Above all, as the abolitionists had dearly hoped and the slaveholders deeply feared, the convention specifically authorized the national government not simply to regulate the Atlantic slave trade but to abolish it.

The proslavery Southerners, wary of their constituents, declared victory, proclaiming the concessions they gained in Philadelphia were sufficient to secure slavery permanently under the new Constitution. As with gradual emancipation, some of the most ardent antislavery advocates, especially in New England, denounced the convention’s work as a sellout to tyranny. Many, if not most, prominent abolitionists, however, including the renowned physician, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and secretary of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society Benjamin Rush, hailed the Constitution, and in particular its provisions on the slave trade, as auguring the commencement of slavery’s eradication. Some could not suppress self-congratulation. “How honorable to America,” one widely-reprinted Pennsylvania Gazette essay observed, “to have been the first Christian power that has borne a testimony” against so “repugnant” a practice as the Atlantic slave trade. How extraordinary, another writer remarked, “that in this new country, we should, in less than 150 years, possess a degree of liberality and humanity, which has been unknown during so many centuries, and which is yet unattained in so many parts of the globe.” In Providence, Rhode Island, an assembly of free people of color more straightforwardly celebrated the Constitution and its “Prospect of a Stop being put to the Trade to Africa in our Fellow-Creatures.”

*

The struggle, barely imaginable to the previous generation, had only just begun. For most of the ensuing seventy years, the slaveholders would secure the initiative in national politics, not because of the three-fifths clause in the Constitution or any other concession from the framers but because of the support they received from northern conservatives. Beginning in the 1790s, the renaissance of American plantation slavery bolstered by a revolution in cotton production turned early visions of a yeoman’s republic into the reality of an American slaveholders’ regime beyond anything slavery’s early champions could have imagined.

Yet the struggle never ceased. As early as the very first Congress, abolitionists shook the House of Representatives with petitions demanding members press to the very limits of their powers to abolish promptly not just the Atlantic slave trade but slavery itself. Here and there, antislavery advocates won some unlikely victories, passing measures (eventually discarded) to choke off slavery’s advance into the newly-acquired Louisiana Territory, fending off proslavery efforts to undermine the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade (achieved at the earliest possible date in 1808), and forcing a major crisis in 1819 and 1820 over the expansion of slavery, concerning Missouri’s admission to the Union. Thirty-five years later, the rise of the Republican Party, devoted to the single object of halting slavery’s expansion in order to hasten its doom, commenced what soon enough became the final conflict.

That history was not harmless. It was not peripheral. Nothing about it was inevitable. It began with perhaps the greatest unforeseen transformation in modern history, the rise of antislavery ideas and arguments. Americans, earlier than anywhere else, turned that transformation into the politics that would seek to bring slavery to its “ultimate extinction.” In reaction, Americans also produced the mightiest proslavery resistance to those politics the world had ever seen and, through the Confederacy, came perilously close to establishing an American empire of slavery, if not for what Lincoln called the “terrible war” that rendered a “result” which was “fundamental and astounding.” Cynicism about this history defeats understanding as surely as complacency does. We are left to contemplate, as both Philip Roth the writer and “Philip Roth” the character he created tried to do, the terror and the triumph of the relentless unforeseen.