The recent publication of two works by the Marquis de Sade enables us to see that sadism is not just “the impulse to cruel and violent treatment of the opposite sex, and the coloring of the idea of such acts with lustful feelings,” as Richard von Krafft-Ebing defined it in his 1886 Psychopathia Sexualis. Sadism, as it is depicted by Sade, is also, and perhaps primarily, the creation of a world in which the powerful and wealthy are able to lure the poor and powerless, hold them captive, and reduce their bodies and selfhoods to nothing.

In this, as some clear-sighted post–World War II writers have noted, Sade’s writing was, inter alia, a harbinger of fascism. Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, for example, wrote that Sade “prefigures the organization, devoid of any substantial goals, which was to encompass the whole of life” under the totalitarianism that drove them from Germany. Reading Sade in the age of #MeToo and Jeffrey Epstein is an uncanny experience, for his novels are also a blueprint for the world of the sexual predators of today.

This winter brings the first complete English translation of Sade’s vast epistolary novel, Aline and Valcour, in a lavish, three-volume edition from Contra Mundum. The translation, by Jocelyne Geneviève Barque and John Galbraith Simmons, is a masterful one, allowing Sade’s prose to flow, neither assuming the language and rhythms of the eighteenth century nor interpolating anachronisms from English today. It is, by all appearances, the work of two people who have studied the writing of Sade deeply and admire it.

Originally published in 1795, Aline and Valcour was, according to its title page, “Écrit à la Bastille un an avant la Révolution de France”—“Written in the Bastille,” where Sade had been held since 1784, “one year before the French Revolution.” The novel stands out from almost every other novel in Sade’s oeuvre in that it is not a work of pornography, though it does not lack for libertines and salacious events. It’s a grab-bag of a book, filled with tales within tales that take the reader to Africa, Portugal, and Spain. Not only is it not pornographic, but it is also a novel in which many of the ideas expressed run counter to those that were central to Sade’s thought.

Sade explains this in a footnote, writing that Aline and Valcour “offers in each letter the correspondent’s own way of thinking or that of the persons involved and to whom he offers his ideas.” If, unlike the rest of Sade’s work, this novel is not solely in his voice, it is because, as the translators explain in their introduction, the author intended to present the range of views held by Enlightenment thinkers, whether he shared them or not. The result is a book in which religion and motherhood, both of which Sade mocked and detested, are praised, and where nature, which Sade viewed as an amoral force that served to explain and justify his characters’ evil, is presented as beneficent.

The first French dictionary to include the word “sadism,” in the mid-nineteenth century, defined it as “a monstrous and anti-social system revolting to nature.” That being so, nothing could be further from Sade than this novel by Sade.

The 120 Days of Sodom, a new translation of which was published as a Penguin Classic in 2016, is another matter entirely. The manuscript of this, the most notorious of Sade’s books, was thought lost when Sade was transferred from the Bastille to Charenton a few days before the prison was stormed on July 14, 1789, and didn’t receive its first French publication until 1904. The challenges that its translators, Will McMorran and Thomas Wynn, faced were far different from those of Barque and Simmons, for McMorran and Wynn’s task was to translate a book that summarizes the Sadeian worldview in all its fury, in all its madness.

It is a work of brutal pornography interspersed with occasional bursts of Sade’s philosophy, a mélange of borrowings from Montaigne’s cultural relativism, Jean Meslier’s atheism, La Mettrie’s materialism, and d’Holbach’s materialist atheism. These philosophical outbursts are sprinkled among countless pages of coprophagy, flatulence, and vomiting (all for erotic purposes); of sodomy and misogyny. Both the content and the worldview expressed in The 120 Days of Sodom make it as close to a repellently unreadable book as has ever been written.

This new translation also happens to be a clumsy one, full of odd and poor choices, the worst of which is a character’s exclaiming, “Golly, sweetheart.” But the infelicities of the translation are of relatively minor concern. The 120 Days of Sodom most clearly poses the problem of Sade’s survival. How has this body of work continued to be read, let alone enjoyed the status of a classic?

Advertisement

Sade, though admired by Flaubert, among others, was, in fact, a figure of little literary consequence until the early twentieth century, when Guillaume Apollinaire rescued him from oblivion, by publishing in 1910 a collection of his novels. Apollinaire proved himself a seer when he wrote in the introduction to his edition that “this man, who seemed to count for nothing for the entire nineteenth century, could very well dominate the twentieth.”

In the century after Sade’s revival, a shocking number of intellectuals fell under his spell, explicated him, and defended him. Their focus was almost always on the philosophy of Sade, on the “transvaluation of values” he performed that would have made Nietzsche blanch. Sade the stylist hardly figures in the commentaries written by his admirers; indeed, it would be hard to make much of a case for writing that is verbose, repetitive, and, for all its sexual explicitness, impoverished. Added to these faults is the sheer bloat of his books: La Nouvelle Justine is 720 pages in the definitive Pleiade edition; L’Histoire de Juliette, 1081 pages; and the new translation of Aline and Valcour, 819 pages.

Nevertheless, Apollinaire set the intellectual template for those who would follow, claiming that “above all, [Sade] loved freedom. Everything—his actions, his philosophical system—testified to his passionate taste for the freedom he was so often deprived of.” Roland Barthes in 1971 upped the stakes in his Sade/Fourier/Loyola, calling Sade “the most libertarian of writers”—a declaration that failed to take account of how, in his supposed “love of freedom,” Sade placed severe limits on the liberties of others, both in his books and in his life. “If one of you should suffer the misfortune of succumbing to the intemperance of our passions,” wrote the great “libertarian” in The 120 Days of Sodom, “let her bravely accept her fate—we are not in this world to live forever, and the best thing that can happen to a woman is to die young.”

Like a guard in a concentration camp, the Sadeian hero is allowed absolute freedom to do whatever he likes to his victims, who are in most cases kidnapped or purchased and imprisoned in castles or chambers from which no escape is possible. In one of many instances that appear to foreshadow the fate of those imprisoned in the Nazis’ camps, Sade wrote, in The 120 Days of Sodom, “Here you are far from France in the depths of an uninhabitable forest, beyond steep mountains, the passes through which were cut off as soon as you had traversed them; you are trapped within an impenetrable citadel.” Even more directly, in a passage from Juliette quoted by Adorno and Horkheimer in their Dialectic of Enlightenment—where they wrote that we find in Sade “a bourgeois existence rationalized even in its breathing spaces”—Sade wrote: “The government itself must control the population. It must possess the means to exterminate the people, should it fear them… and nothing should weigh in the balance of its justice except its own interests or passions.”

Apollinaire was first followed by the Surrealists. In 1926, Paul Éluard praised Sade in the movement’s organ, La Révolution Surrealiste, writing that “for having wanted to infuse civilized man with the power of his primitive instincts, for having wanted to free the romantic imagination, and for having desperately fought for absolute justice and equality, the Marquis de Sade was imprisoned almost his entire life in the Bastille, Vincennes and Charenton.” André Breton went even further, saying in a 1928 discussion of sexuality that, “By definition everything is allowed a man like the Marquis de Sade, for whom the freedom of morality was a matter of life and death.” We get an idea of Sade’s notion of “absolute justice and equality” in The 120 Days of Sodom, where he wrote: “Wherever men shall be equal and where differences shall cease to exist, happiness too shall cease to exist.”

Some of this affection on the part of the Surrealists for the “divine marquis” can be written off as provocation, the avant-garde desire to épater le bourgeois. But Sade’s novels seemed to them a guide in their search for a new mode of being that escaped all and any limits. It was precisely the extent that Sade violated all taboos, social and sexual, that made him a member of their pantheon. But in elevating Sade, the Surrealists had no choice but to read him selectively, to elide the terror that this supposed ethic of personal liberation imposes on others. The freedom of the one existed at the price of the oppression of everyone else, of their reduction, in fact, to mere orifices.

Advertisement

*

Then, in the aftermath of World War II, there was an extraordinary explosion of analyses of Sade. Pierre Klossowski, in his 1947 Sade, mon prochain, claimed that Sade was a man deeply influenced by Christian mystics. In a 1951 article in Les Temps modernes, Simone de Beauvoir famously asked: “Must We Burn Sade?” Answering in the negative, Beauvoir was not reticent in pointing out the flaws and contradictions of Sadeian thought. Warning against a “too easy sympathy” for him, she wrote, “it is my unhappiness he wants; my subjection and my death.” Still, she concluded by enlisting him in the Existentialist cause, saying that: “He forces us to put in question the essential problem that haunts this time in other forms: the true relationship between man and man.”

Georges Bataille, however, viewed the matter very differently in his 1957 L’Érotisme. For Bataille, Sade’s theme is the isolation of the subject. The sexuality expressed in his books excludes the possibility of any real contact, and the people with which he and his characters engage “cannot be partners, but victims.” Even more, his literature portrays the image of “a man for whom others cease to exist.”

Roland Barthes provided an answer to the question of whether Sade must be burned by sheltering behind “discourse.” The “sole Sadeian universe” is that of “the universe of discourse.” Any offense taken at the acts in Sade’s novels is unjustified because it fails to take account of the “irrealism” of his books. “[W]hat happens in a novel by Sade is strictly fabulous, i.e., impossible.” To condemn Sade’s books is to fall into the trap of “a certain system of literature, and this system is that of realism.”

But the notion that Sade was a purveyor of “irrealism,” that his life had nothing to do with his novels, does not stand up to scrutiny. The difference between the crimes he committed in life and those he depicted in his novels is one of degree and not of kind. In 1768, in the Parisian suburb of Arcueil, Sade induced a beggar, Rose Keller, to accompany him home, promising her a job as a housekeeper. When they arrived at their destination, Sade threw Keller onto a bed, tied her to it, whipped her until she bled, sliced her skin with a penknife, and dripped hot wax on her. Though she filed a complaint and he was briefly imprisoned, family influence resulted in his release.

Four years later, in Marseilles, Sade sent his valet to recruit what a biographer called some “very young” girls for a debauch. In the end, seven people would participate in the event, the young women whipped and at least one of them sodomized, and the victims drugged with Spanish fly. This abducting of young girls with whom he would have sex, and his locking of victims in castles so they could not escape his desires, occurs in all of Sade’s novels, turning them, on the contrary, into realist, even autobiographical, fiction.

Imprisoned for the Marseilles escapade, Sade would escape, and within three years he found himself involved in yet another sexual scandal. He was finally imprisoned in 1777 under a lettre de cachet, a royal order for arrest without trial, obtained by his mother-in-law to protect family honor against any further criminal sexual exploits. Sade would remain imprisoned until the Revolution abolished the lettre de cachet in 1790. Arrested again in 1801, under Napoleon, and held at Sainte-Pélagie prison, Sade was transferred to the asylum at Charenton in 1803 after attempting to seduce fellow inmates at Sainte-Pélagie. It was in Charenton that he organized the theatrical productions immortalized by Peter Weiss in his 1963 play Marat/Sade, and where Sade would die in 1814. While in the asylum, at age seventy-four, in what a biographer called “his least glorious phase,” he regularly sodomized (for payment and with her mother’s consent) a young woman of sixteen, Madeleine Leclerc, noting the frequency of his acts in a journal.

Not all postwar intellectuals fell under the sway of the divine marquis or saw him as simply a philosopher who lived his ideas in a more extreme way than others. Some saw the fascism latent in his novels—and said so explicitly, as Raymond Queneau did in 1945: “all who embraced the marquis’s idea to one degree or another must now envision, without hypocrisy, the reality of the death camps, with their horrors no longer confined within a man’s head but practiced by thousands of fanatics.” Camus noted in The Rebel, published in 1951, that the “ideal society” constructed by Sade “exalted totalitarian societies in the name of liberty.” And it was the cinematic provocateur Pier Paolo Pasolini who presented the connections between Sade and fascism most starkly of all in his final film, the 1975 Salò or The 120 Days of Sodom); there the book’s brutalities are enacted under the flag of Mussolini’s Social Republic.

Sade’s attraction for some has nevertheless persisted—as the most extreme example of counter-Enlightenment thought, the voice of the abolition of reason. It was, after all, the very impotence of reason that was made so starkly and horrifyingly manifest in the two world wars and the period between. Sade’s exclusive concern with the sovereignty of the individual, on an absolute freedom from any constraint, continued to lure a certain class of intellectuals in a period of mass politics. In Weiss’s Marat/Sade, the two historical figures embody the most radical expressions of these dichotomous forms of rebellion: the political and the individual. As Beauvoir wrote of him, “Sade supposed there could exist no other road than that of individual rebellion.”

This was his weakness, but it was also a source of his enduring appeal. And so, Sade survived. But can his oeuvre survive our own time? And should it?

*

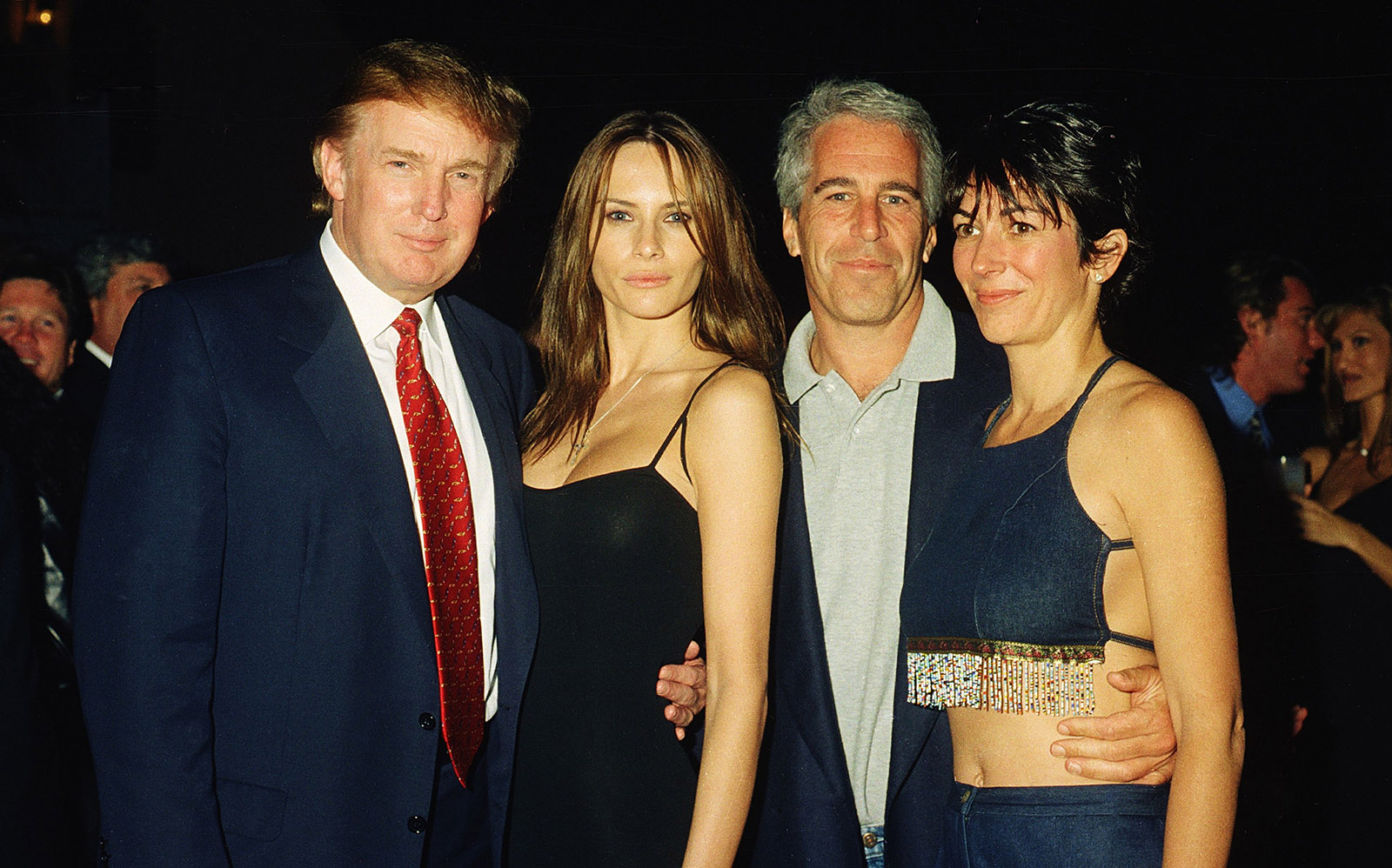

It is impossible not to think of Jeffrey Epstein and his accomplices when reading Sade. In The 120 Days of Sodom, the age of the girls delivered to the libertines “was fixed between twelve and fifteen and anything above or below was ruthlessly rejected.” And in Aline and Valcour, two libertines “keep a seraglio of twelve young girls… of whom the oldest is not yet fifteen, and is replaced at the rate of one a month.”

Epstein’s plane was flippantly and familiarly known as the Lolita Express; in one reported incident, a twenty-three-year-old woman brought to him was rejected as too old. Like Sade, Epstein had hirelings to procure his victims. The financier’s procuresses lived well, as did those in Sade’s work, who in 120 Days received “thirty thousand francs—all expenses paid—for each subject found to their liking (it is extraordinary how much all this cost).”

The libertines in Sade, to quote Barthes, also “belong to the aristocracy, or more exactly (and more frequently) to the class of financiers, professionals, and prevaricators.” And like the victims of Epstein, those victimized and assaulted by Sade’s characters in his fiction, as by Sade himself in real life, “belong to the industrial and urban sub-proletariat.” The power differential that plays such an important part in the contemporary scandals is limned in the biography and writing of Sade. It was Camus who summed up the Sadeian universe as one of “power and hatred,” a term just as aptly applicable to Epstein’s world.

Epstein’s Caribbean island, to which young women were flown, his ranch, and his townhouse are a contemporary version of the castles in which Sade’s fictional and actual victims were assaulted. Just as in the case of Sade, where the will of the victims was ignored, their lives reduced to obeying the libertines’ orders, Epstein’s girls were at times referred to as his friend Ghislaine Maxwell’s “slave[s].” As the victims in the pages of Sade hear: “no one knows you are here… you’re already dead to the world and it is only for our pleasures that you are breathing now.”

According to court documents, Epstein “required different girls to be scheduled every day of the week,” just as 120 Days records the drawing up of a timetable to detail which victim will perform which act on which day. Epstein’s regimen recalls Sade’s character in Les Infortunes de la virtue who explains that “I make use of women from need, the same way one makes use of a chamber pot for a different need.”

Epstein carried on with virtual impunity until the final reckoning, like the libertine in Sade’s 120 Days who would “commit excesses that would have sent his head to the scaffold a thousand times were it not for his influence and his gold, which saved him from this fate a thousand times.” Sade’s books are a guidebook to, and prophecy of, the Epstein case.

In one important way, though, this looking-glass is reversible: it is Epstein who illuminates Sade and allows us to read the French aristocrat with a different eye. Sade lived his drives, and when imprisoned, he turned them into literature. That literature is still read and is still the subject of serious study. Some recent books, for example, have viewed Sade through the lens of queer theory, examining his vision of sex and death, once again placing him within the framework of Enlightenment thought.

But we might justly ask: Had Jeffrey Epstein lived and become a writer, would his literary output have enthralled us?

There is no indication that Epstein ever committed to paper his ideas and fantasies, as Sade did so obsessively. Sade, after all, viewed himself not just as a libertine, but as a philosopher of libertinism (one of his works was titled Philosophy in the Boudoir). His flights of fancy served to relieve the privations of his confinement, perhaps, but they were also the basis for an encompassing worldview like few others.

Unlike Sade, Epstein did not elevate his tastes into a principle. And that Epstein left no account suggests a consciousness of the legal jeopardy any such record would create. But if Epstein had done so, would anyone have dared write of him, as Breton did of Sade, that he was someone “for whom the freedom of morality was a matter of life and death”? For both men, the freedom of morality was, in actuality, a freedom from morality, a license to inflict pain on others.

There are two nouns Sade uses heavily in his novels that sum up the Sadeian universe: victime and scélérat, victim and villain. This is the only moral division of any significance in his works—and it perfectly summarizes the worlds of both Sade and Epstein. “Laws are null and void as concerns scoundrels,” wrote Sade, “for they do not reach he who is powerful, and he who is happy is not subject to them.” Both men acted and lived in accordance with that dictum.

If Beauvoir was right and Sade forces us to question “the true relationship between man and man,” then Epstein’s predations present us with an unalloyed vision of precisely how money and power twist those relations. To change that requires an utter rejection of Sade’s philosophical system, as succinctly expressed in a line from Justine: “My neighbor is nothing to me; there is not the least little relationship between him and me.”

We need not burn Sade, but neither should we praise him. His spirit still wanders among us, and we must use him to see why we have our Epsteins.