When federal judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was appointed the first commissioner of baseball in 1920 to clean up the “Black Sox” World Series scandal from the year before, he knew that the future of the sport he loved was on the line. Not only had several members of the Chicago White Sox plainly thrown the series against the Cincinnati Reds on behalf of Arnold Rothstein, kingpin of the New York mob, but a number of other players for other teams were also widely known to be in league with gamblers. A Chicago jury had cleared eight of the Sox of conspiracy, but Judge Landis knew that baseball would never recover its integrity if he, too, flinched on any of the wrongdoing. In his final report, Landis declared:

Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player that throws a ball game, no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ball game, no player that sits in a conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing a game are planned and discussed, and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball.

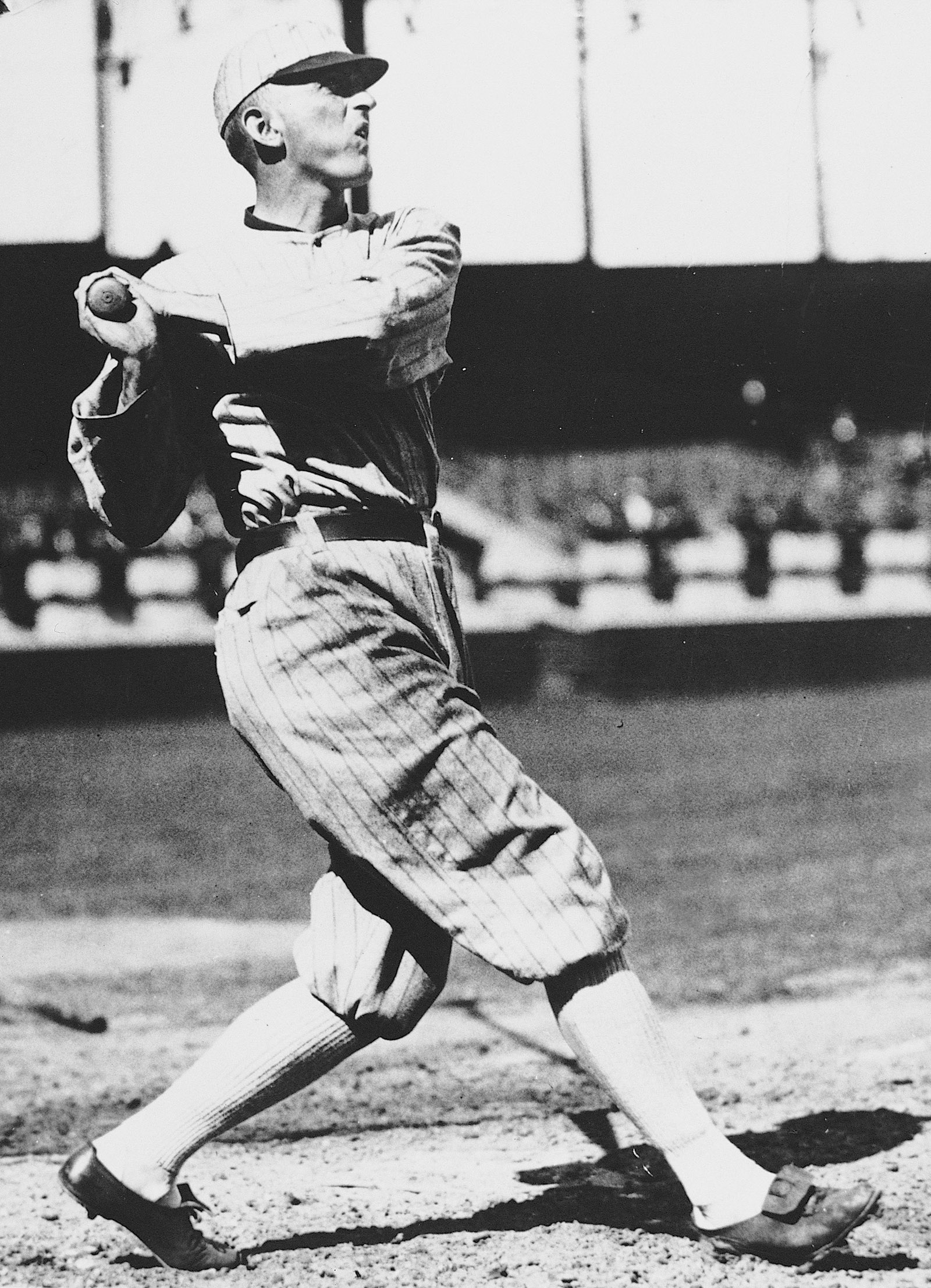

He summarily banished eight Chicago players, including at least one who was only minimally involved in the plot, if at all, the all-time great “Shoeless” Joe Jackson. Not only had Jackson declined to play poorly during the series; he hit a sterling .375 while setting a record for most base hits that would stand until 1964; and he played flawlessly in the outfield. But he knew about what was going on when one of the complicit players threw $5,000 on his bed, so he was done.

Because of Landis’s ban, Jackson has remained ineligible for induction into baseball’s Hall of Fame, an honor that, strictly on the merits of his playing, he utterly deserves. And because of Landis’s broader determination to rescue baseball’s good name, the judge banished thirteen more players during his tenure as commissioner, for infractions ranging from bribery, gambling, and fixing games to an accusation of selling a stolen automobile (even though the alleged player-thief had been acquitted of the charge). Landis’s critics claimed that he was unduly severe, not least with his condemnation of the hapless Joe Jackson. Yet from the time he took over until his death in 1944, baseball never again suffered a disabling disgrace on the order of the Black Sox scandal. Landis may have been draconian, but he kept the game above suspicion of being rigged.

Only a few years after Landis died, the legendary 1951 New York Giants team devised an illicit sign-stealing scheme in their home park, the Polo Grounds. The conspiracy wound up propelling a team with an indifferent record at mid-season into a three-game pennant playoff with the Brooklyn Dodgers, which the Giants won at the last minute with Bobby Thomson’s famous “Shot Heard ’Round the World” home run. Experts have since ascertained that the Giants owed their stunning success to the cheating, but the scandal only came to light fifty years later, so no one was punished. Its memory lives today only as salt to be poured into the still-open wounds of aging Brooklyn Dodger fans, who, six years after losing that playoff, lost their team to Los Angeles.

The scandals did not end. More discovered over the last thirty years have resulted in harsh penalties assessed on specific players. The great hitter Pete Rose’s betting on baseball, exposed in 1989, was peanuts compared to the offenses of either the Black Sox or the 1951 Giants. While managing the Cincinnati Reds at the end of the 1980s, Rose, the all-time major league leader in hits, placed wagers on baseball games—but never against his own team, which would have been deeply suspicious. Still, Rose, like the Black Sox, was banished for life, which makes him, like Joe Jackson, ineligible for the Hall of Fame.

The steroid use scandal uncovered in 2004, which, compared to Rose’s betting, involved far greater offenses to the game’s integrity, brought no banishments. Still, more than eighty players have suffered suspensions ranging from ten games to an entire season for violating the drug policy adopted by Major League Baseball in the wake of the revelations; one repeat offender, Jenrry Mejía, a New York Mets pitcher, was suspended permanently in 2016, though reinstated two years later by the current commissioner, Rob Manfred; and the shame attached to steroid use has excluded several retired all-star players, including the all-time home run leader, Barry Bonds, from entering the Hall of Fame.

Which brings us to the crushing scandal that enveloped baseball as this year’s spring training commenced, involving the Houston Astros’, and possibly the Boston Red Sox’s, exploitation of a high-tech version of the 1951 Giants’ sign-stealing conspiracy. Even before all the facts have come in, it is by far the worst disgrace ever to hit the game and could well cripple it. The Black Sox infractions involved a few players’ fixing a few games in a single World Series; the Giants’ involved an entire team, or the better part of one, cheating for half a season and possibly in the 1951 World Series (to no avail if it happened, as the Giants lost badly to the far superior New York Yankees). The Pete Rose and steroid scandals hardly compare with these.

Advertisement

The Astros’ cheating, however, involved, at the very least, the front office as well as players’ devising and deploying a variety of intricate schemes to steal signs of the opposing teams for at least the entire 2017 season and post-season, in which they actually won the World Series; and it may have continued through the 2018 and 2019 seasons and post-seasons, in which they won one division championship and one American League pennant. The 2018 Boston Red Sox, another World Series winner, may also be implicated, as their manager that year, Alex Cora, may have been heavily involved in setting up the Astros’ cheating systems. That is, the validity of the last three seasons of major league play have been seriously called into question.

Short of severe penalties, the sport that Judge Landis tried with success to render unriggable will look like a mug’s game, run by moguls eager for the glory as well as the tens and maybe hundreds of millions of dollars that accrue from winning championships and played by multi-millionaires who cheat not so much for the money—unlike the underpaid Black Sox—but for the sheer delight of winning it all, even if it means winning dirty. It will put a new spin on the adage of the 1951 Giants’ manager Leo Durocher about nice guys finishing last: now, the best cheaters stand to finish first, and everyone else, including the fans, are suckers. A perfect sports scandal for the age of Trump.

Commissioner Manfred, seemed at first, to take the scandal seriously, as did the Astros and Red Sox team owners, and a couple of managers lost their jobs, and the Astros lost some prime draft picks and a $5 million fine. But Manfred also did something that may simply have been stupid, may have been craven, and may have been corrupt: extending blanket immunity to the players before launching a proper investigation. Since then, a series of exposés—unearthed not by Major League Baseball but by the press (above all, the estimable online magazine The Athletic)—has shown that the scandal runs much deeper than first revealed, from higher-ups who knew all about what was happening down to the players who helped invent, and then eagerly participated in, the cheating.

The non-apology apologies delivered by Astros players, as well as team owner Jim Crane, when spring training opened have only worsened the perception that the franchise either has no conception of the damage it has done to the game or does understand but couldn’t care less. “I feel horrible for our sport, our game, our fans, our city, our organization,” remarked star outfielder George Springer, an admitted participant—as if a criminal is supposed to feel bad for the team and the city and fans he cheated for, instead of the teams, cities, and fans he cheated against.

Anything less than a full-scale reversal will add the taint of a cover-up to crimes that, if left unpunished, could easily destroy the business of baseball, to say nothing of the sport itself. Until and unless Commissioner Manfred lifts his ludicrous immunity offer and deals severely with the incriminated participating players as well as their management by banishing them all from the game, he will have thrown baseball back to where it was in 1919. Doing the right thing won’t be easy, especially as Manfred will have to deal not just with the owner moguls but with a players’ union that will fight any suspensions, let alone banishments, tooth and claw, and may already have brokered the immunity agreement. But Manfred, though he has so far chosen to defend the indefensible non-apology apologies, has history on his side.

If he were to follow Landis’s rules, this would include banning stars like second baseman José Altuve, who claim they knew what was going on, refused to take part, but who also clammed up. In a show of mercy, if he accepts explanations like this at face value, Manfred might spare characters like Altuve—but only in the interest of equal justice that the existing bans be lifted on Shoeless Joe Jackson and Pete Rose, and with encouragement to the baseball writers who vote on the matter to elect Jackson and Rose to the Hall of Fame.

Advertisement

Either way, baseball faces a moment of truth unlike any it has known in a century. If he continues feebly to accede to the corruption of baseball, Commissioner Manfred should himself be forced to wander in the eternal purgatory of the field of dreams inhabited by the Black Sox. What would Judge Landis rule? You’re out!