In January of 1985, when I was in sixth grade, my mother, a piano teacher at the Krasnodar State Institute of Culture, decided to use a small sum she’d inherited from my late grandfather for a winter break trip to Moscow. We arrived by the same express train my grandfather used to take when traveling to the Ministry of Foreign Trade for work, and stayed in the same place he and my mom had stayed in during her winter breaks—the huge Hotel Rossiya built to host Party congresses’ delegates, right across from Red Square. By the time of our visit, twenty years later, the hotel had lost much of its luster, its once-flagship furniture now worn, the bathroom tiles cracking. But from the window of our “half-lux,” we could see the brick towers of the Kremlin, and the gray Moskva River, frozen inside its granite embankment.

For provincials like my mother and me, Moscow meant a small break from the daily vicissitudes of late-period Soviet life. Everything was better in Moscow: the food, the shops, the theaters. It was the seat of the Party leadership, a fact that guaranteed better supplies, and a place where foreigners from the other side of the Iron Curtain visited, so effort went into showing what the USSR had achieved—even if it hadn’t, in fact—with spillover benefits for the Muscovites and domestic visitors. It was during that winter break in Moscow, in the magnificent Eliseevsky Grocery, all marble and crystal, that I laid eyes on great triangular mounds of kubanskaya, a type of first-class dry salami that was produced in the Southern Russian town where we lived but long since vanished from its stores’ counters.

Moscow’s theaters happily combined refinements of food and culture, so my mother made sure we visited as many as we could in the six days of our vacation. Theater-going was affordable as a rule, and children’s tickets were half-priced. The problem, like so much else in the USSR, was that tickets to good shows were not in “open distribution.” To get in, you had to know someone, which left outsiders like us at a distinct disadvantage. And good shows that you could buy tickets to came with a “burden,” as it was known, of less popular amusements. To see The Jungle, a musical featuring real monkeys at the Children’s Theater, we had also to buy tickets to the Variety Theater, whose three-hour program turned out to be a dull affair. Luckily, the buffets at both were great, with smoked keta salmon sandwiches and intricate pastries that were a far cry from the stale éclairs of the Krasnodar Operetta, where we were regulars thanks to my mother’s affiliation with official culture.

The one theater to which tickets were impossible to get, even with a “burden,” was the Bolshoi. Its huge neo-classical portico topped by an Apollo-driven quadriga was tantalizingly close, no more than a twenty-minute walk from the hotel, but it might as well have been on the moon: not a single theater kiosk sold tickets to the ballet. This frustrated my mother. When she had traveled to Moscow, in better days before she was married, Grandfather was always able to get reservations through the ministry. And my mother strove to give me what she once had, but her opportunities were limited. The women in the ticket kiosks advised us to go to the Bolshoi itself before the show and try to get tickets from the scalpers. My mother, who never bought anything on the black market, hesitated.

On the last day of our stay, as we were leaving the Lenin State Library, where my mother had been plowing through various doctoral theses on cultural enlightenment with the hopes of one day producing her own and improving our material standing, we learned from the poster freshly glued on an advertising column that the opera The Tsar’s Bride, which had been playing at the Bolshoi all the previous week, had been succeeded by Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet. That sealed our plans for the evening. With music by the great Modernist composer, and with the Bolshoi’s rising star, Nadezhda Pavlova, as Juliet, this was, according to my mother, the ballet to see. Despite drawing a blank, as expected, at the three kiosks we hustled to, my mother was determined.

That last afternoon in Moscow, the weather finally changed. It grew slightly warmer, to -10 degrees Fahrenheit or so, and the previously cloudless sky turned gray. As we set out for the Bolshoi, the first snowflakes appeared, touching up the symmetrical branches of the blue spruces along the Kremlin Wall and the fur hats of the Mausoleum guards. Light at first, the snowfall quickly became heavier, covering gray asphalt and frozen dirt, quieting the clanging of trams and the revving of car engines, as though someone had turned the volume down, making the buildings of our cold capital seem softer, less severe.

Advertisement

By the time we reached the Bolshoi, its magnificent portico illuminated for the evening performance, the trees and fountains of Sverdlov Square were swathed in white. Even the granite Karl Marx facing the theater no longer looked as though he was trying to break out of the massive rock but was leaning into it, rather.

The vestibule of the box office was packed, its marble floor slippery from the melting snow shaken off boots and mink hats. Ignoring the “NO TICKETS” sign, people were busily elbowing their way to the counter to hand over various scraps of paper in exchange for the supposedly nonexistent tickets. When we asked these theater-goers if they had “an extra”—a strategy that two days earlier had secured us a ticket to the Kremlin Yolka, the USSR’s most coveted kids’ holiday show, in the Palace of Congresses—they just shook their heads and turned away. Shivering inside her silver coat of synthetic fur, adequate for our southern winters but obviously lacking here in Moscow, my mother remained optimistic. Veterans of begging for extra tickets knew that it took only one yes.

As we loitered between the columns of the theater’s entrance, an unshaven middle-aged man in jeans and puffy short jacket sidled up. “Balcony, fifth tier,” he said in a low voice, flashing a fan of tickets. “Sixty rubles.” At that rate, a pair of tickets would have cost almost a month’s wages for my mother at the Institute of Culture. “We’ll see nothing but the chandelier from up there,” she said, trying and failing not to show outrage. The man smirked—“If you want front row, pay with dollars”—then walked back to a group of smoking men, whose uniform of foreign jeans indicated first-hand acquaintance with dollars. My mother said, “We’ll see.”

It looked increasingly, however, as if the despicable sharper was right. The majority of people headed into the Bolshoi were not single mothers seeking to impart culture to their daughters, but well-dressed, easy-smiling foreigners. At least a dozen of their comfortable Intourist buses with darkened windows had pulled up since the beginning of our quest. “Why don’t you go to the group entrance and ask them for extra tickets in English,” my mother said, brushing off the small snowdrift that kept accumulating on my red-and-yellow shapka-kosynka, a girl’s version of the babushka. “That’s your way to practice.”

Having studied English at a specialized school for three years, I longed to interact with “bearers of the language.” Yet, each time I rushed to open the door of an arriving bus, I’d get brushed aside by a grim Intourist guide before I could impress its occupants with my knowledge of Shakespeare’s idiom. I did get a couple of embarrassed smiles, and a man wearing a Red Army hat inquired of the tour guide on my behalf, to no avail. These groups did not even need tickets, I soon came to realize: the tour guides simply showed the printout with names to the doorman, who then crossed each foreigner’s name off a list.

No, I told my mother for the fifth time, I did not want just one sixty-ruble ticket.

“Look, Amerikantsy!”

She pointed at a small group approaching from the Hotel Metropol side: two women in evening dresses and a man wearing a baseball cap, all gesticulating and talking animatedly. The Americans were on foot, without a tour guide, and there were only three of them. Perhaps, we both thought, one of the party was missing her pair.

We were spot-on. After listening to my plea, a woman in a sparkling black gown and a bell-shaped cloak of real fur exchanged a few words with her companions, smiled, then clicked open her lacquered clutch and pulled out a ticket. In my exultant state, I didn’t understand exactly what she said, but I felt her friendly pat on the back of my coat of black plush.

“Mama,” I shouted at the top of my lungs, waving the ticket victoriously. “I got it! Orchestra!”

Unlike my mother, I didn’t see a man running toward me. It was just that suddenly there was nothing in my hand, still raised above my head. I only saw him running away—with my ticket—pushing aside some passers-by, the crest of his red shapka bobbing between fur coats and dublyonkas, then disappearing into the snow, along with Romeo and Juliet, the rising star Nadezhda Pavlova, and everything good in this world.

Advertisement

The rest I remember only haphazardly—the way my hands felt so cold inside my mittens, wet from the tears I was wiping, the barely discernible smell of naphthalene coming off my mother’s prickly woolen scarf as she pressed me to her chest, someone’s voice instructing her to go to militia, another saying, “They’re all in on it.” At some point, after following her blindly, I remember staring at the slanted beam falling from the street lamp, thick with snow, while she pleaded with someone at the service entrance, her words reaching me only every now and then, as though through a blanket— “You understand…” “How can they do this to a child?” “She just won’t stop crying.” Followed by, “Yes, she is perfectly fine to go alone. God bless you, comrade!”

A maze of corridors smelling of theater glue and hot irons for the costumes. A white staircase under a worn red carpet-runner, wet footprints here and there. I followed the nameless comrade through the halls of the renowned theater, still dazed, my bulky black coat and wild-colored hat reflecting in the gold-framed mirrors. Would he really fetch my mother during intermission, as he’d promised? Would anyone really leave after the first act, having “check-marked” the Bolshoi, and free up other seats? Would my mother catch pneumonia as she waited in her thin coat and light boots with their jammed zipper on the theater’s cold marble steps? On that silent journey through the balustraded foyers, we seemed alone, the man and I; the show must have started already. In the well-heated theater, I felt a little nauseated in my outdoor clothes.

Inside a crescent red corridor, an old-fashioned candelabra cast faint light on the plaque “Bel-étage.” Stopping before one of the doors, through which the muffled sound of an orchestra was coming, the man let go of my hand and, with the words “Take any empty seat,” pushed me into the darkness.

A row of gilded armchairs with curved legs. An enormous crystal chandelier glinting above. Straight ahead, hugged by tiers of crimson and gold, the famous Bolshoi stage, wide and deep enough to look like a medieval piazza, with a real fountain in the middle. In the box—for this is where I was, I realized—the last chair of the front row was empty. Slipping off my coat, I tiptoed forward.

From my seat, if I’d leaned over the velvet barrier and to my right, I could have touched the ornate column of the Tsar’s Box. Yet I remained motionless, gripped by the strange, anxious music that seemed to be pouring from everywhere, the walls, the painted ceiling, the very air of the theater, reaching into my soul, dissolving the bitterness of the recent injustice, and filling, at least for the moment, the absence I always felt since my grandfather had died, as though a button had been ripped from a piece of fabric. I still longed for my mother to be there, but the real world was slowly receding. I listened. And I watched.

I wasn’t exactly new to ballet. I had seen a few productions at the Operetta Theater, and danced myself when I was little. I’d also read, three times, the biography of prima ballerina—and Hero of Socialist Labor—Galina Ulanova, The Story of One Girl, watched Anna Pavlova on wide screen in full color, and knew Swan Lake by heart, because it was broadcast on all three TV channels every time a general secretary of the Party died, and they seemed to die often in those days. But watching Romeo and Juliet at the Bolshoi, it was as though I had seen nothing of ballet.

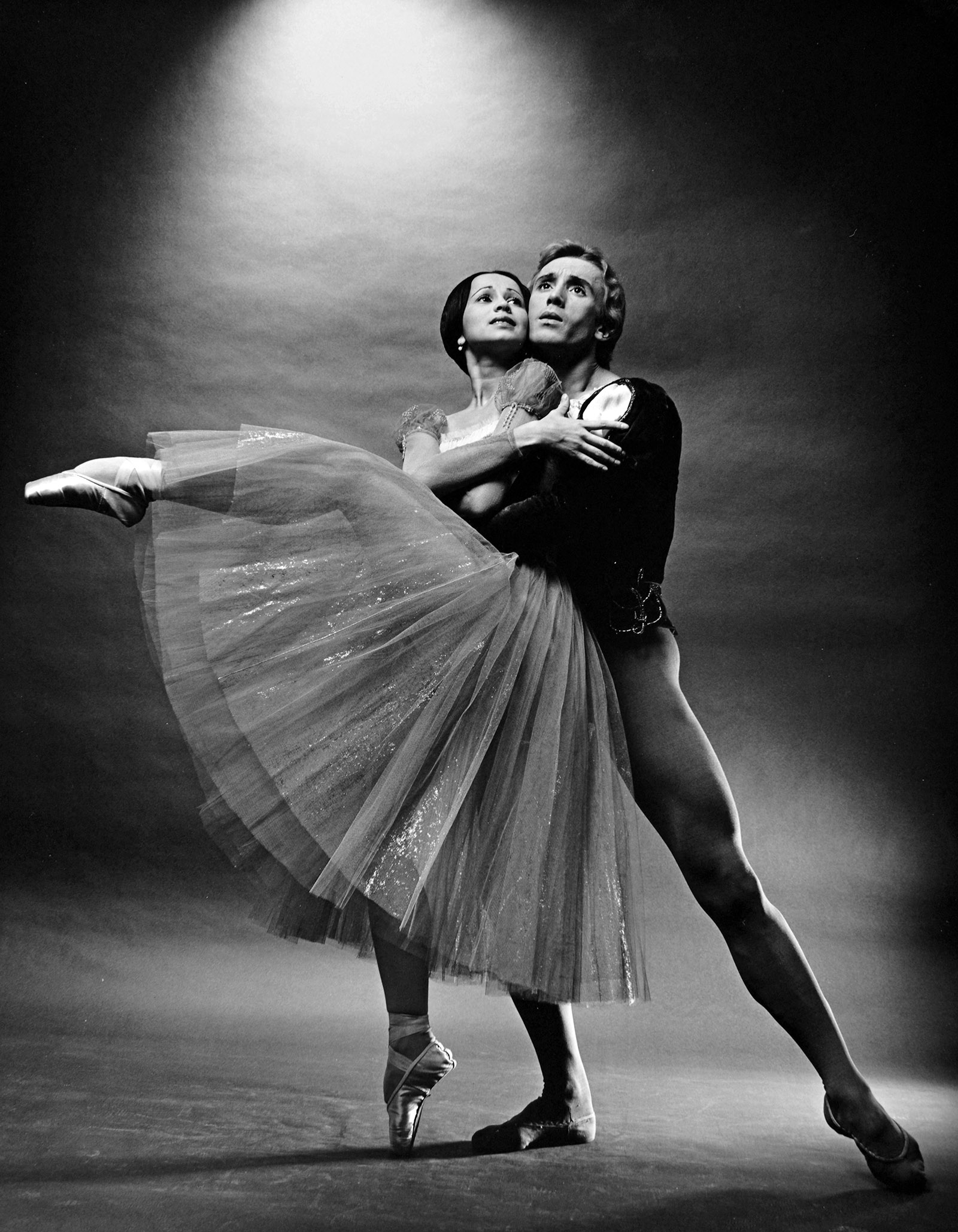

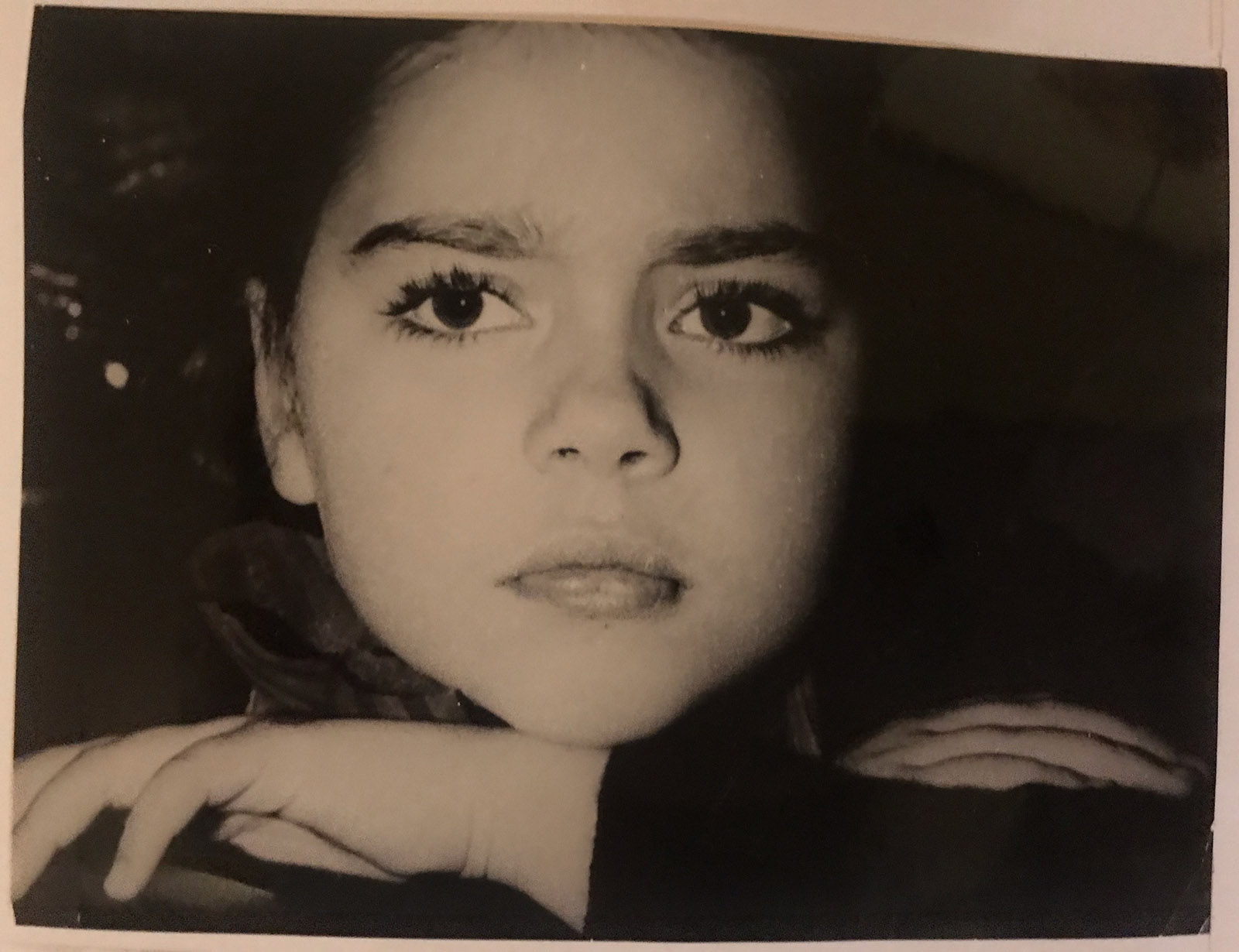

On the stage, grand dance sequences flashed before my eyes. Famous dancers, the glory of the country—men tall and handsome, ballerinas seemingly cut from a piece of ivory by the same masterful hand—leaped and lunged in perfect unison, their costumes lavish, their movements flawless. In her white plisse dress and pearl hairnet, Nadya Pavlova looked every bit the living illustration from The Story of One Girl, her body bending at impossible angles as she flitted across the stage, her bourrées and attitudes pure and delicate, like the love that awaited her. Each time she smiled, I smiled, and each time she frowned, I frowned. The music, light yet tense, made me want to cry. When I could, at the end of each number, I clapped until my palms hurt.

With a rise and fall of the curtain, the stage transformed itself from a lady’s chamber into a colonnaded ballroom. Soon, Juliet—and I—would meet her Romeo; I knew that from the Book of Theater Librettos I liked to read. The score turned dark, foreboding. Under the vaulted ceiling, supported by columns six times taller than the height of a man, Montague and Capulet couples faced each other in a dance as fierce as war, their backs erect, knights’ cloaks flaring, long trains of their women’s dresses gleaming under the bright stage lights, all to that piercing theme that swung from fortes to pianissimos then back to fortes, booming trombones and French horns giving way to gentle flutes and pizzicato strings. This “Dance of the Knights” overwhelmed me, awed me. Entering the box during the intermission, just as she’d promised, my mother found me with my elbows on the velvet barrier, chin on clasped hands, staring at the curtain.

By the time the ballet was over, the snow had stopped. The streets around the Bolshoi were lined with pristine snowdrifts, and the farther we went from the theater, the higher they seemed to grow—saved from the plow trucks by the late hour on this last Friday of the winter break, the long hand of the illuminated Spasskaya Tower Clock trembling onward with each passing minute.

We must have spoken about the show, but those words have left my memory. All I remember is the music playing in my head and the vast expanse of snow.

Under the awning of the hotel’s entrance, a man in a flat Georgian cap stood smoking. Looking on as I brushed the snow off my coat, he remarked, “What a blizzard,” with a shake of his head. My mother laughed, her eyes very green in the light from the lobby. Somewhere behind us, the long hand of the Spasskaya Clock reached its zenith, and the commanding ring of the Kremlin chimes drifted over the frozen river and the swallow-tailed battlements. As the last strike reverberated, I took my mother’s hand and followed her inside.