I vividly remember the winter day in 1954 when I first saw the equestrian statue of General Baquedano presiding over one of the emblematic plazas of Santiago de Chile. I was a wide-eyed Argentine-born child of twelve, just arrived from the United States, and listening carefully to the man driving my family around the city that was to become my new home after ten years in New York. He was a colleague of my father’s from the regional office of the United Nations and considered himself an expert on all things Chilean. He waved with enthusiasm at the statue—soldier and horse—looming gigantically above us as he heaped praise on the nineteenth-century general.

“Manuel Baquedano,” he gushed. “One of the heroes who made today’s Chile, unified the nation. Forged as a young officer in the battles that pacified the Araucanian tribes in the south, he went on to win the war in the north against Peru and Bolivia that added rich territories to the fatherland.” He then pointed toward the mountains that could be viewed splendidly from the large, open space: “Up there is where you will be living, the barrio alto,” meaning where the more prosperous members of society resided, “and down there,” indicating behind him the rest of the nation’s capital is “where everybody else lives.”

I didn’t notice it at the time, but as I grew into adolescence and manhood, I realized at some point how symbolic it was that General Baquedano was facing the disadvantaged areas of Santiago, as if to resist the hordes that might someday be tempted to cross the line dividing the rich from those who were less fortunate, a chasm that has marked the history of this country ever since the Spanish conquistadors dislodged the original native inhabitants from their ancestral homes and created a semifeudal system that exploited peons, lands, and mines. And what I certainly couldn’t have anticipated, on that remote day in 1954, was that sixty-five years later, the Plaza Baquedano (also known as Plaza Italia) would become the epicenter of a social revolt that has unsettled the foundations of the Chilean state, redefining how the nation conceives of itself.

Indeed, since the estallido, or explosion, of October 18, 2019, the plaza has been occupied permanently by intrepid activists who have unofficially baptized it as Plaza de la Dignidad, the site where, they loudly proclaim, their dignity and the dignity of Chile are being restored. The choice of that location to shatter, symbolically and spatially, the border between the two Chiles is a deliberately transgressive way of declaring that in order for a new country to be born, the old boundaries and myths need to be demolished.

As for the statue, though still standing despite fervent efforts to topple it, the general and his steed are now covered with paint and graffiti, as desecrated as the surrounding streets that, for many blocks, resemble a war zone: a burnt-out metro station, boarded-up shops, hotels, and restaurants, with murals, posters, and slogans on every available wall. The rubble is ubiquitous, a seemingly inexhaustible source of rocks and paving stones used by encapuchados (masked combatants) as missiles when they clash with the police, attesting both to battles past and to battles yet to come.

Not all is violence and demolition. In front of Baquedano’s statue, maverick artists have installed three wooden sculptures that personify the indigenous tribes of Chile, from north to south. Most moving of these attempts to express the defiant identities of the most submerged and silenced sectors of society is a homage to the exterminated Selk’nam people of Patagonia, a pietà that seems to mourn the death of a whole culture.

Who can doubt that if General Baquedano, the embodiment of Chile’s official history of conquest and domination, were to revive he would find the plaza—as well as the country he helped to create and supposedly unify—unrecognizable.

He would not be the only one.

At the very moment when, on October 6, 2019, high school students were igniting the first sparks of the rebellion by joyously jumping the turnstiles of a number of subway stations to protest a fare hike, Chile’s right-wing president, Sebastián Piñera, was boasting on a television program that the country was “an oasis” in a turbulent and convulsed Latin America. The clueless leader, like most of Chile’s elite, did not realize what was already erupting from the depths of a country he did not understand. Instead of acknowledging the anger behind this peaceful and playful defiance of norms—the students chanted that they had the right to “evade” the tariff just as the corrupt owners of Chile’s economy were incessantly “evading” any form of reckoning—Piñera’s government responded with a ferocious repression, further alienating large swaths of the citizenry.

Advertisement

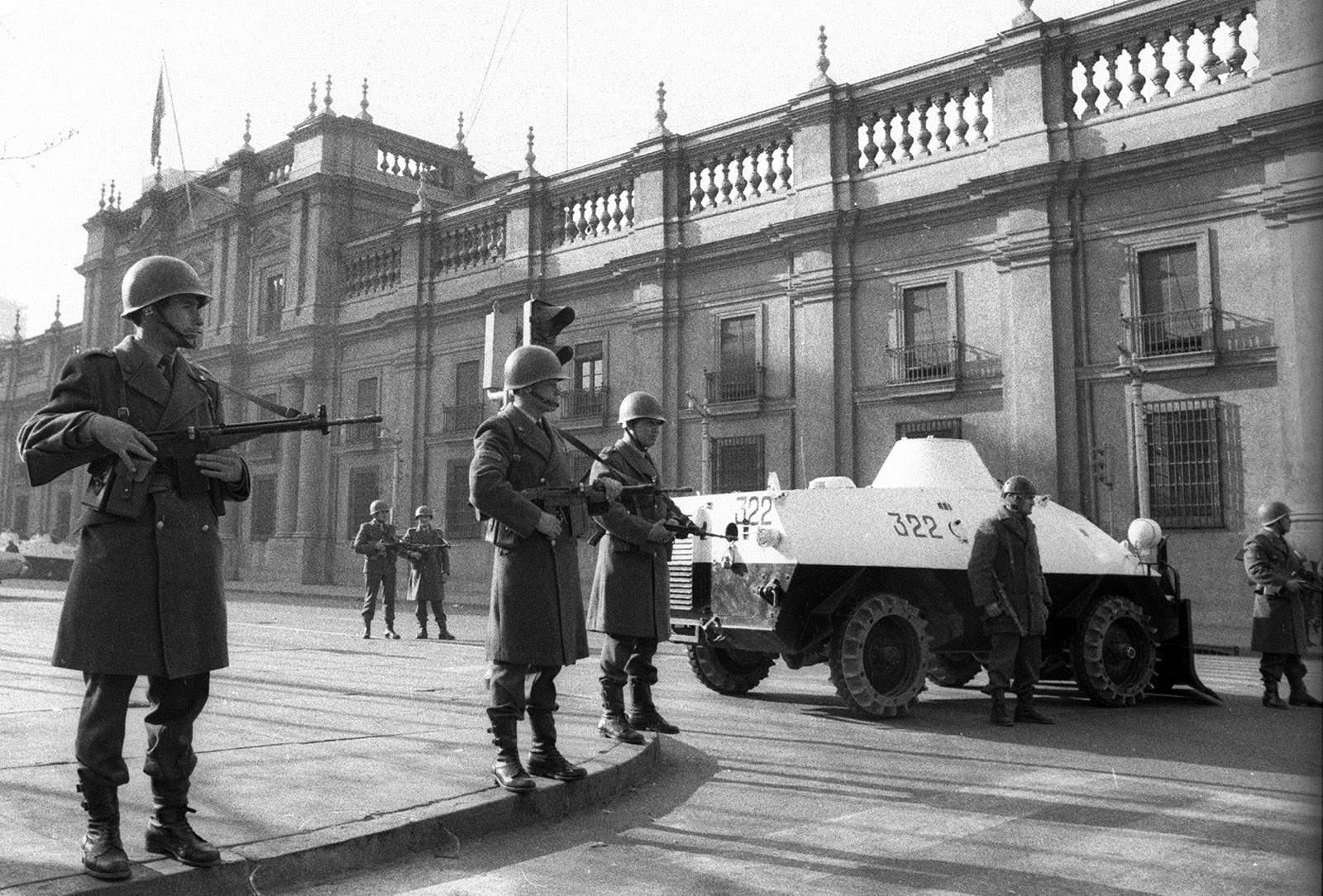

The hostilities escalated. The police committed human rights violations on a scale not seen since the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet (1973–1990): thousands of arrests, indiscriminate beatings, rapes in police stations, unrestricted use of toxic water cannons intentionally aimed at the eyes of demonstrators. In response, the most enraged protesters built barricades and torched buses, metro stations, and big chain supermarkets. As Chile’s major cities descended into a maelstrom, Piñera gave yet more proof of how badly he was misreading the country’s mood. Slandering the demands of protesters for a just and fair society as an attempt to turn Chile into Venezuela, and declaring that this was a war against a powerful enemy sustained by forces from abroad, the president decreed a state of emergency and ordered the military to enforce a curfew.

The combination of such belligerent rhetoric, which recalled the justifications used by Pinochet to persecute dissidents, with actual tanks on the streets once again, further outraged the people of Chile, many of whom had struggled so hard, and at such a steep cost in suffering, to get the military out of their lives. On October 25, millions of men, women, and children serenely flooded cities and towns all over the country, spontaneously repudiating the repression and calling for its perpetrators to be punished.

Such a nationwide assembly, the largest in our history, was unique in several ways. In contrast to every other march in living memory, this one was not organized by political parties, all of which, right, center and left, had fallen into utter disrepute with an increasingly disaffected and skeptical electorate and an underclass of primarily young people who were constantly promised paradise tomorrow while they lived a version of hell today. Instead of slogans proclaimed from above, a heterogeneous set of aspirations emerged from below: changes in the unfair health and education systems, a drastic reform of the pension plans (which had been privatized under Pinochet), better salaries, and controls on the disgraceful prices of basic goods. To these were added an impassioned defense of the environment; demands to cease the mistreatment of women, gays, lesbians, abandoned children, even animals; the return of ancestral lands to the country’s indigenous inhabitants; and a call to manage the country’s water and rivers not through private corporations, but by the state and the affected communities.

Behind these critiques of the status quo something more fundamental was brewing: the need to question and replace the neoliberal economic paradigm that had dominated the country since the overthrow in 1973 of the socialist government of President Salvador Allende and that had led to the ostentatious enrichment of an obscenely opulent minority. As to how to resolve the immediate crisis politically, the masses began—as they organized in scores of town hall meetings—to coalesce around one overarching idea: that the current Constitution, imposed illegitimately by Pinochet in 1980 and used by conservative forces to stymie any efforts at transformation, be superseded by a new Magna Carta created by and for the people themselves.

Would the government finally listen? Were the perennial owners of Chile’s wealth scared enough to make concessions, and ready, as the president’s wife had admitted, “to give up some of our privileges”? And would the center-left parties, whose members control both houses of Congress, accept that they had contributed to the predicament by not attending to the real needs of the people?

The answer came soon enough. As support for the social mobilization grew—along with the chaos, vandalism, and violence—parties from across the political spectrum, all seeking to regain lost legitimacy, agreed on an itinerary establishing steps toward a new Constitution. And measures, albeit insufficient, were taken to address some of the most flagrant inequalities plaguing the educational, health, and pension systems, along with taxation reforms.

On April 26, a referendum will be held to determine if there will be a new Constitution and what the makeup of the convention to compose it should be (either entirely of newly elected representatives or half current members of Congress). The hope is that the process leading to that referendum, which is supposed to engage all of Chile in a discussion about what sort of country its people desire, will channel the energies of the protesters.

It may not be an easy journey.

*

I have visited the new, liberated Plaza Baquedano several times during the months of my latest stay in Chile. This is not only because I am fascinated with the promises and contradictions of the social movement that dares to imagine a totally new country, but because that site also happens to retain an irrevocable place in my own life, in ways that perhaps might also illuminate the life of the larger nation in which I had arrived as a boy of twelve and that I soon adopted as my own.

Eleven years after that 1954 arrival, I felt thoroughly Chilean. By then, I was working at the Universidad de Chile, from which I had received a master’s degree in literature, and was engaged to be married to my extremely Chilean girlfriend, Angélica. And on the political front, we had been participating actively in a revolutionary movement that was sweeping Latin America and the rest of what was then called the third world. Like so many of my comrades across the globe I dreamed of creating a land free from the chains of the past by eliminating, once and for all, the distance that separates the very rich from the desperately poor. One of the ways of signaling that participation for the young, back then, as now in 2020, was by taking to the streets, and one of the perennial targets of those protests was the United States of America.

So it was that Angélica and I found ourselves, on May 6, 1965, crossing the Plaza Baquedano with thousands of other demonstrators, primarily affluent university students, heading for the US embassy, just two blocks away, to protest the recent American invasion of the Dominican Republic—yet one more arrogant and bloody Yankee intervention in the internal affairs of our Latin American republics.

At the edge of the plaza, we were met by a phalanx of riot police, but we managed to skirt them and proceed to the Parque Forestal, a small park in front of the fortified embassy building. There, we were soon dispersed by an attack that took us entirely by surprise: we were used to a sort of elegant ballet of the police advancing, the protesters dispersing and regrouping, but there was no back and forth this time. When Angélica and I skittered away, a menacing police van pursued us through the gardens and tried repeatedly to ram us against one of the trees we tried to hide behind. Finally, chased by several burly police officers wielding nightsticks, we managed to scurry our way back to the plaza, which seemed to offer a semblance of refuge.

Perhaps because the police, as if they still recognized some sort of boundary of privilege that had to be respected, made no further attempts to assault the chanting throngs of well-to-do students that had reassembled there, we did not yet realize that we had been given a foretaste of the future. These brutal new methods of crowd control were part of a well-funded modernization of repressive measures, systematic and precise, in Chile and the rest of an insurgent Latin America. If dissidents and activists were not yet subjected to the full force of state violence, this was due to Chile’s resolutely moving, in the years that followed, toward the possibility of popular control of that state through a peaceful revolution. And in effect, on September 4, 1970, a coalition of left-wing parties elected a new president: Salvador Allende, a socialist who was committed to structural reforms of Chile’s inequitable economy and society, but through democratic means rather than by armed struggle.

That election dramatically altered what the plaza meant to Chileans. The multitudinous marches of the Allendistas purposely streamed through the square in a show of strength and support for our experiment, proof that the city belonged to those who had built and nurtured it and not to those who profited from the incessant exploitation and neglect of its inhabitants. Besides participating in those marches, at which I shouted myself hoarse with jubilation, my own particular experience of the plaza was also transformed.

By early 1971, I was crossing it three or four times a week on my way to Quimantú, the government publishing house where, after teaching at the university, I was working as an ad honorem consultant on a series of projects: new youth and culture magazines, comic books designed to challenge Disney’s ascendancy in the market, and the publication of popular books sold in vast numbers in inexpensive editions at newsstands. One of the delights of that labor of love was, after several hours of strenuous and exhilarating work at Quimantú, to stop at a corner of the plaza and, for a few minutes, simply stand and watch my fellow citizens acquiring this reading matter at a kiosk. There was the additional reward, later on the bus taking me to my next revolutionary task, of seeing people actually reading, actually absorbed in the words and images I had helped, in my own small way, to bring into the world.

This colossal democratization of culture ran in tandem with the larger flowering of Chilean democracy. Allende’s government wrested control of the country back from the corporations, big landowners, and foreign companies that had owned our resources, our haciendas, our factories, our banks. Making the economy and its surpluses work for the many and not for the few paid for spectacular advances in education and health, a nutrition program for children, and policies that favored indigenous people and improved opportunities for women. And it all came with a torrent of creativity in intellectual life, in the arts, music, photography, literature, and documentary cinema.

This extraordinary experiment in social liberation was abruptly ended by Pinochet’s military coup that, with active assistance from the United States, overthrew Allende’s elected government on September 11, 1973.

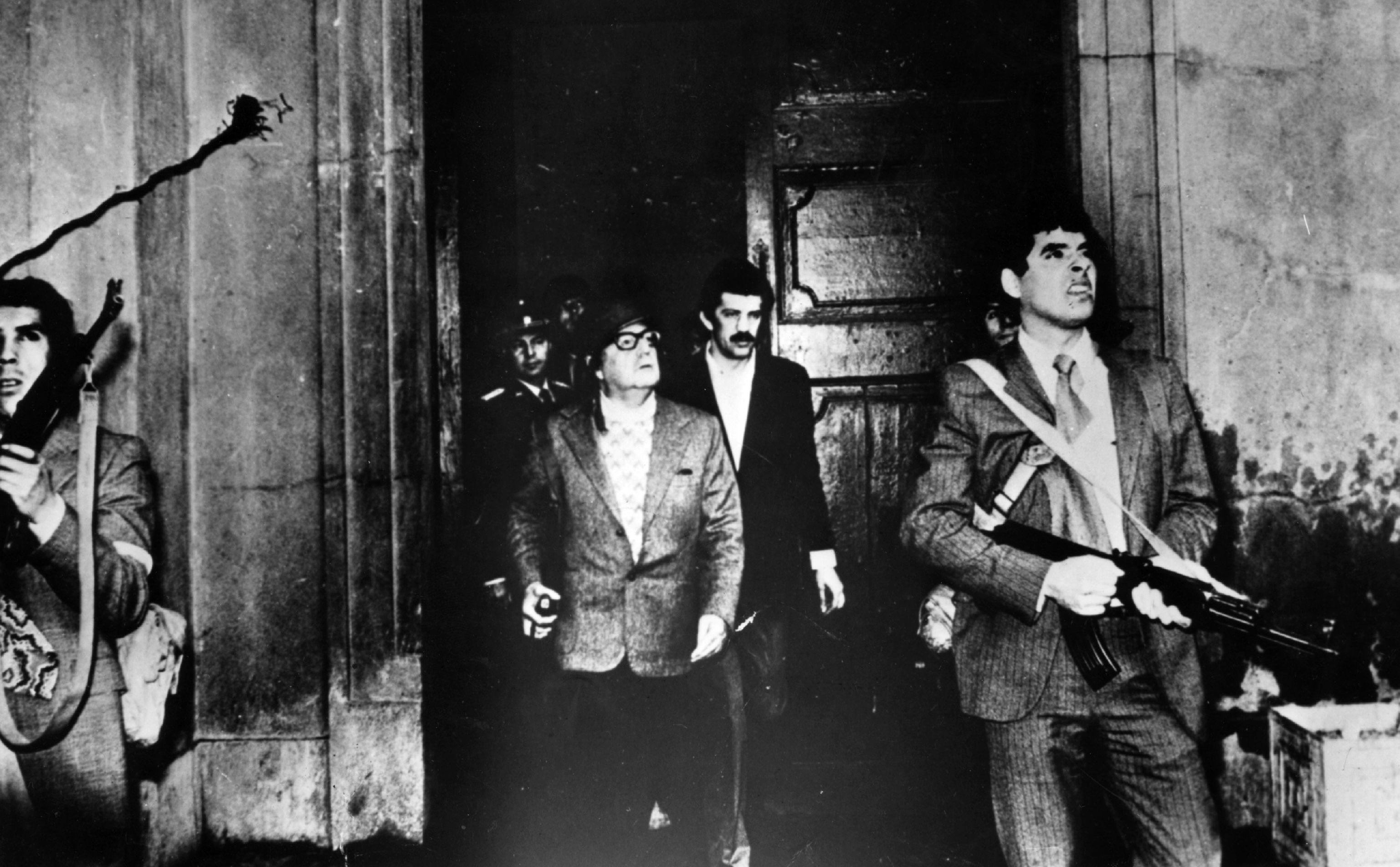

In what proved to be the last months of the Allende administration, I had clung to the hope, as had the revolutionary movement I belonged to, that enough members of the armed forces would remain loyal to the Constitution and would, with the support of the workers and students, defend democracy. Even though this scenario seemed unlikely, I had believed in it with such vigor that I’d accepted a job at the presidential palace of La Moneda as the press and culture adviser to Fernando Flores, Allende’s chief of staff (secretario general de gobierno). I should have been there, soon after daybreak that September morning, but I was expressly left off the list of people to be called at dawn in case of a coup. (Flores told me, years later, that he had saved my life because “somebody had to tell the story.”)

All the same, when we heard what was happening, I persuaded Angélica to drive me downtown to La Moneda, where Allende, surrounded by advisers, bodyguards, friends, and his two daughters, was making a last stand. We were stopped—where else?—at Plaza Baquedano. A hefty barricade manned by armed police officers blocked our way. I got out of the car, approached the captain in charge, flashed my official credentials, and told him I needed to reach La Moneda. He was quiet, letting me listen to the shots resounding from the government loyalists and from the troops firing back all the way down the ten blocks I would have to cross to get to my destination. “At your own risk,” he said, after a long pause.

Looking back at Angélica, who had decided to wait in the car, with the engine still running, I chose not to sacrifice my life, and instead of joining those who would die with Allende that day, or be captured and tortured, imprisoned and disappeared, instead of being by his side as the air force bombarded the presidential palace, I got back in the car with my wife and we drove away from the plaza.

Physically, we left it behind, but in my mind it remained, forever transmogrified: henceforth it would always be the place where I had been forced to accept that we had been defeated and that our dream of peaceful revolution and deep democracy had, far from prevailing, ended in death and destruction.

The Plaza Baquedano would, from that day on, be a haunted zone of my existence.

The general on his horse, intact and resplendent, now presided over a country where the army he had bequeathed to the nation was busy massacring workers and artists, torturing dissidents in stadiums, raping housewives in barracks, and persecuting indigenous peasants in the south and miners in the north. As I hid in a series of safe houses during the weeks following the coup, I thought often of that plaza, which no longer belonged to the readers of the books published by Quimantú but to those who burned those books and anything else they regarded as subversive literature. The lesson in terror was clear: the new authorities wanted to make sure that Chileans would never again question the hierarchies of society or the inequality that would curse us, supposedly, forever.

From the exile into which I eventually journeyed, I watched the ravaging of the land I had come to love, but was encouraged by the resistance to that onslaught, which, by 1983, had grown strong enough to contest the streets of Chile’s cities with barricades and protests not dissimilar to the ones shaking the country today. Among the concessions to which the dictatorship agreed in a vain attempt to quell the unrest was the return of some of the exiles.

And so it was that, ten years after the coup, Angélica and I were again in Santiago marching and shouting defiance, though it was not till 1985 that our family was able to settle in Chile for what we thought was a permanent return. And it was again at the plaza that another central event in my life awaited me.

*

On April 28, 1986, a group of several hundred boisterous activists congregated in the square with toy telescopes to bid farewell to Halley’s comet, begging it to take Pinochet away as it left Earth behind—just as it seemed to have taken Duvalier from Haiti and Marcos from the Philippines. I wonder now whether, by joining that carnival at the very site where, thirteen years earlier, I had been either not foolish or not courageous enough to go on to La Moneda, I was trying to prove something, exorcise some demon of shame at not having died in the cause of the revolution I had sworn to defend. Or am I imposing on that Ariel my current perspective, as I admire the valor of the today’s young rebels, who are palpably unafraid of the police or the army and fight their oppressors to a standstill?

At any rate, I exorcised no demons that night. It was the demons that descended upon me. Soldiers who were posted nearby found nothing funny in our mocking of their commander in chief and, led by a hawk-nosed lieutenant, his face smeared with black paint, proceeded to beat us with the butts of their rifles. I stumbled, fell to the ground, received several kicks, was told to get the fuck out of there—an order I did not hesitate to obey. As I staggered away, I escaped being shot by a young recruit whom I mollified by somehow appealing to our common humanity.

It was a sobering experience—to have escaped death at the very spot where I had avoided it the day of the coup—and it helped to confirm my certainty that it was not through violence, as some on the Chilean far left then believed, that we would be rid of military rule, but by organizing peacefully and ultimately defeating our tyrant at the ballot box. And effectively, I got my wish when, in October 1988, the country overwhelmingly voted “NO” to Pinochet in a referendum the dictator never expected to lose.

By March 1990, Pinochet, though he retained command of the armed forces, was handing the reins of government over to Patricio Aylwin, the leader of the Concertación, a coalition that grouped his own Christian Democrats (most of whom had supported and applauded the coup) with many former supporters of Allende. That alliance cemented for Chile a stable center-left that would run the country for twenty-four of the next thirty years. In order to do so, there were certain limits to which the Concertación consented. Many of the antidemocratic constraints with which conservative forces would sabotage and veto fundamental reforms remained in place. So, just as crucially, did the model of economic development and exploitation that the Pinochet regime had viciously imposed on a helpless citizenry.

Thanks to a softening and partial reform of those policies, some notable advances were attained: a substantial decrease in poverty, improvements in the health system, a program of significant modernization and infrastructure projects. But, whether through fear of another military intervention or because it had become a complacent part of the system, the center-left that had been responsible for guiding the country toward democracy failed to mobilize the people against its neoliberal economic model. The result of that failure was to create rampant consumerism that left millions indebted far beyond their means and a gigantic disparity of income between the very rich and just about everybody else. As the economist Joseph Stiglitz recently noted: “When I looked at the data from Chile, the level of inequality was so high that I was surprised there were not more civilian disturbances.”

When those disturbances did finally explode, in October 2019, it was to contest not just inequality but every institution that had allowed such a situation to fester with blatant impunity. The corruption of the political class through secret campaign contributions added to the sense that those in power, even if elected, were complicit. The Catholic Church—that was once at the forefront of defending human rights during the dictatorship and had acted as a mediator between warring factions in past crises—was now held in contempt thanks to the evidence of extensive abuse of children by priests, covered up by the clerical hierarchy. The government, the center-left leaders in Congress, the police, the armed forces, the judicial system… all were viewed with mistrust.

I understood that disenchantment all too well. It had led me and my family to leave Chile at the end of 1990. As there seemed nothing we could do to keep alive the dream of radical change that had sustained our existence through the dark years of the dictatorship, I preferred the distance of living as an expatriate. That way, I felt, far from the morass of indifference and greed that seemed to be consuming the land, I would be free to write without the daily exasperation of watching the country lose its way. But that was my choice, one not available to most Chileans.

Now that this discontent has, thirty years on, led to such a vast revolt, it is imperative for Chile to work out a solution that is not individual but collective; otherwise, the situation could quickly turn volatile and dangerous. If everyone in office or with power is suspect, who is to lead us out of the labyrinth? The popular uprising that has shaken Chile to its core has not, so far, provided sufficient answers.

*

When Angélica and I arrived back in Chile last December, for one of our occasional prolonged stays, almost everyone we spoke to was filled with enthusiasm and elation: there would be a new Constitution, they were convinced; the conservative forces that had dominated Chile’s economy were on the run, and major concessions to the demands of the people for social reform were inevitable. People derided the government’s emphasis on the need, no matter the human cost, to maintain law and order as a hypocritical ploy to distract the public from the growing consensus for radical change.

Unfortunately, during this hot, agitated Southern Hemisphere summer, the looting of supermarkets has continued, and churches have been burned and police stations and barracks attacked by encapuchados. Obdurate students, insisting that everyone be admitted for free to higher education, have disrupted university entrance exams. As more protesters have been beaten and killed, and more riots ensue to exact justice for them, the violence has gradually become the main subject of discussion, rather than the injustices that have provoked it. Particularly in the less prosperous areas of many cities, where the besieged police have retreated into their bunkers and no longer patrol neighborhoods, residents run a daily gauntlet of assault and robbery by young hoodlums armed with guns and knives—several people close to our family have suffered such attacks. Even museums and cultural centers have been reduced to ashes (though some claim that the police themselves have been responsible for this kind of vandalism).

The uncertainty and dread affecting many Chileans, the sense that this carnage leaves nothing sacred intact, has given an opening to the more reactionary forces behind the government to pull back from their original assent to a new Constitution—scared out of their wits, they reluctantly felt that this was the only way to avoid a full-scale revolution that would sweep them from power. There are still significant right-wing sectors, led by three of their most popular politicians, Mario Desbordes, Joaquín Lavín, and the mayor of Santiago, Felipe Alessandri, that have continued to push for a new Magna Carta; and there are even some—notably, Finance Minister Ignacio Briones—who stress a progressive social agenda. But a majority of former Pinochet supporters, pressured by the far-right politician José Antonio Kast, a neofascist admirer of Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, have come out against the reforms. They’re now mounting a ferocious campaign of fear, hoping that the unabated violence, disruption, and economic crisis will persuade the Chilean people to reject a path portrayed as turning the country into another Venezuela.

Thus far, this counternarrative of order versus disorder has not much eroded the overwhelming support for a new Constitution, which hovers near 70 percent. But this number may diminish drastically, depending, in great measure, on how the most aggressive agitators act in the coming months. When I spoke recently to a number of them at the Plaza de la Dignidad, they told me that they did not intend to tone down their militancy. It was the only way, they said, to maintain pressure on the establishment to approve the radical transformation Chile yearns for.

I was hesitant to raise my reservations about their tactics, worrying whether I had forfeited that right when I left Chile rather than stay behind and fight for a different future for these youngsters. Despite this vague feeling of guilt, I raised the concern that their movement was being hijacked by delinquents and narcotraffickers who were exploiting the turmoil to extend greater control over the poorer neighborhoods. The protesters’ response was passionate: as fighters for freedom and justice and, yes, love, they were sick of being unfairly vilified by the media and the government. Many of those committing crimes, they claimed, were either in the pay of the authorities or at least had their tacit consent, in order to sow confusion and dread. (This is a theory that has also been floated by some intellectuals and journalists.)

The young activists insisted that shadowy forces taking advantage of the unrest were not a reason to scale back their legitimate protests. They were proud of what they’d accomplished—not only in forcing the political establishment to listen to the fractured voices of Chile’s most neglected, but also in providing those voices with a multitude of new spaces and arenas where they could be heard and engage with one another in a spirit of solidarity.

And no matter what the ultimate outcome of the estallido may be, one thing is certain: Chile has been living an extraordinary outburst of creativity the likes of which we had not experienced since the Allende years. Thousands of cabildos, or town-hall meetings, have taken place; new rap songs have been written and ballads rediscovered (the anthem of the movement is “El derecho de vivir en paz,” the right to live in peace, by Víctor Jara, the great folk singer who was murdered by the military shortly after the 1973 coup). Documentaries and plays, too, have proliferated, along with art installations throughout the land, including the one celebrating indigenous history at the Plaza de la Dignidad and Un Violador en tu camino (“A Rapist in Your Path”), a feminist performance piece with an empowering message urging women to accuse their tormentors that has been repeated in cities all across the world.

But nowhere is the sense of liberation more striking and sophisticated than in the mural paintings and posters that adorn walls everywhere, often the work of art students who continue a long tradition in Latin America and, specifically, in Chile during the revolutionary years of Allende. Two images are repeated across many of these representations. One features a black Labrador dog with a red kerchief tied around its neck. This is the negro matapacos, in honor of a legendary mutt that did not “kill cops,” as its name implies, but barked fiercely at them during the street battles. When it was shot and killed, it was resurrected in many another black stray across the country and the human mascot of street warriors who, for their part, have made the mistreatment of animals, as well as of humans, their cause. If the matapacos motif is so pervasive, it may be because the activists feel that they, too, are homeless in a land that should belong to them; they, too, are ready to die.

Above all, though, the presence of this iconic dog allows the protesters to communicate their tenderness, best exemplified by an anecdote told to me by one of the young women at the plaza. At a protest in the northern city of Antofagasta, the local matapacos was severely injured by police pellets but eluded all efforts to be taken to a veterinary surgeon. The frustrated protesters decided to simulate a march, pretending that they were incensed about something or other, and the dog quickly joined them as, fists lifted high, they strode vociferously into the clinic where their untamed pet was captured, sedated, and cured of its wounds. It is now back on the streets taking part in real rallies.

Just as ubiquitous as the image of the matapacos are the eyes dripping blood that have edged into almost every graphic representation, a reminder of the police brutality that has left more than three hundred protesters partially blinded by pellet fire. Those eyes are an homage to the victims, proof that their sacrifice will not be forgotten, that blood of beloved comrades will be paid for with blood of the enemy, that other eyes are vigilant and awake.

The image also helps to explain the intransigence of the activists: their determination not to abandon the struggle until those who have perpetrated these attacks are put on trial and punished (including, of course, the president and anyone who might suggest he should not resign or be jailed). Though I am impressed by their courage—the more so as I did not, during my own experiences at the plaza, show a similar fearlessness—I worry that this fury may be on the verge of devouring them. Their anger may inspire them in their battles, but however justifiable as a response to the unnecessary pain they see in the world and as a form of loyalty to their dead comrades, such rage is not the best counselor when it comes to making allies for the difficult negotiations required to ensure a transition to fuller democracy and bring the structural reform the country needs.

The social media that enable the rebels to organize and assemble promptly and efficiently also function as a closed echo chamber that often seems to trap them in a self-righteousness that does not tolerate nuances or dissident views. This emotional overconfidence has led to a deterioration of the sort of rational discourse that any nation needs in order to forge unity out of the profound differences that separate adversaries. These radicals, impatient and anarchic, do not appear to have a strategy that can achieve their utopian goals. One problem is that they tend to consider the state as the enemy to be destroyed rather than a series of institutions that can be conquered and adapted to serve the needs of the people.

It may be that I am missing the point. The most confrontational protesters want no return to a nation that is falsely unified, pretending we are all friends, a nation where some loot and exploit and lie and others suffer—the real looters, they assert, are the corporations, not those who steal from stores. They want no return to normality when “normality is the problem,” as one of the most popular slogans goes. They want the boundaries of the old plaza abolished, not papered over.

Am I making too much of these potential limitations in the protest movement, in all its most attractive and fascinating aspects? Is my perspective perhaps distorted by the trauma of witnessing how the peaceful Allende revolution was derailed by some of the socialist president’s own most extreme supporters, who scared the middle classes with their wild rhetoric and actions and gave ammunition to its most implacable adversaries?

I remain, nevertheless, cautiously optimistic that the Chilean people will find a way forward, that the door that has opened to a different Chile, as a recent video advocating for a new Constitution proclaims, will never again be closed. I hold onto the hope that by targeting the plaza, which symbolizes the invisible ramparts erected since the military coup and reinforced in its long aftermath, the protesters have succeeded in resurrecting the memory of the site where the people once marched for freedom and citizens bought books and everyone felt the future was in their hands.

My stubborn hope in this continuing resistance has been encouraged by a recent event. One Sunday in February, Angélica and I were enjoying a quick lunch at a mall cafeteria with a view of the majestic Andes cordillera in the distance. Suddenly, in the streets below, cyclists began to appear by the hundreds and then by the thousands; there must have been at least ten thousand passing by, with banners proclaiming all kinds of aspirations. I was aware of the regular weekend gathering of bicycle riders who congregated in front of La Moneda Presidential Palace to call Piñera an asesino (a killer), but this group seemed to be heading toward a stadium where Colo-Colo, the most popular of the soccer league teams, was playing.

It was a tense national moment. Not long before, a police van had run over a Colo-Colo fan but a judge had freed its driver, leading to deadly riots nationwide (with four more dead and hundreds of police stations beleaguered by picketers). But these cyclists were calm and orderly, their flow monitored by marshals who stopped traffic and made sure there were no troubles (indeed, the news that night reported no incidents at the stadium). Notably also, these protesters were escorted, at the front and the back of the demonstration, by two police outriders on motorcycles, offering the sort of protection that lately has come to feel rare from the forces of law and order. I felt I had caught a brief glimpse of what the city might be like if we ever managed to think—and bike—our way out of the current crisis.

Chile despertó! (Chile has awakened!) is the most popular and succinct expression of what the revolt hopes to accomplish. Whether this assertion presages our future path or the nightmare of history will once again catch up with us will be determined by the millions who, like those ten thousand cyclists, continue to peacefully organize for a time when dignidad will be something that does not lodge in a solitary plaza but lives throughout the whole country, a Chile that deserves a better fate.