A little over one hundred years ago, a novel virus emerged from an unknown animal reservoir and seeded itself silently in settlements around the world. Then, in the closing months of World War I, as if from nowhere, the infection exploded in multiple countries and continents at more or less the same time. From Boston to Cape Town, and London to Mumbai, the “Spanish flu,” so-called because the first widely reported outbreak occurred in Madrid in May 1918, swept like wildfire through cities and communities both large and small.

By the time the virus had burned itself out, in the spring of 1919, a third of the world’s population had been infected and at least 50 million people were dead. That is 40 million more than perished on the killing fields of Flanders and northern France (and elsewhere in Europe), and 10 million more than have died from AIDS in the forty years since the syndrome was first recognized in the 1980s.

Yet, except for those who watched loved ones succumb to the deadly pneumonic complications of Spanish flu, or who nursed patients on influenza wards and lost colleagues to the infection, the virus left relatively little mark on the collective consciousness of society. “Americans took little notice of the pandemic,” noted the environmental historian Alfred Crosby America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (1989), “then quickly forgot whatever they did notice.”

The Times of London was similarly puzzled by the pandemic’s failure to leave an emotional residue. “So vast was the catastrophe and so ubiquitous its prevalence that our minds, surfeited with the horrors of war, refused to realize it,” opined an editorial in “The Thunderer” in February 1921. “It came and went, a hurricane across the green fields of life, sweeping away our youth in hundreds of thousands and leaving behind it a toll of sickness and infirmity which will not be reckoned in this generation.”

Even now, just three months into the pandemic of Covid-19, it seems there’s little danger of the coronavirus being similarly forgotten by historians. Although, at the time of writing, the global death toll stands at a modest 6,610, SARS-CoV-2, to give the virus its official name, has already crashed world stock markets, grounded the international aviation industry, and sparked nationwide-wide lockdowns in Italy, France, Spain, and Iran. Now, with Europe in the eye of the storm and North America next in line to feel its full blast, President Trump’s assurances that Covid-19 “will go very quickly” are looking more vacuous by the day.

As the full scale of the challenge presented by Covid-19 becomes apparent to governments, and as the World Health Organization’s director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, issues increasingly pointed warnings about the need for countries “to take urgent and aggressive action,” so those who are familiar with the history and science of pandemics have grown increasingly anxious that history may be about to repeat itself. As Bill Gates pointed out in a recent commentary in The New England Journal of Medicine:

Global health experts have been saying for years that another pandemic whose speed and severity rivaled those of the 1918 influenza epidemic was a matter not of if but of when… Covid-19 has started behaving a lot like the once-in-a-century pathogen we’ve been worried about.

Infectious disease experts at the Francis Crick Institute, Britain’s leading biomedical research center, concur. As one researcher put it in a recent email to a colleague: “This is NOT business as usual. This will be different from what anyone living has ever experienced. The closest comparator is 1918 influenza.”

*

As someone who has been studying and writing about pandemics for more than fifteen years, I share these concerns. My interest in the subject began in 2005 when I interviewed John Oxford, a professor of virology at Queen Mary and Westfield School of Medicine, in London, about avian influenza. A few months earlier, a strain of the H5N1 bird flu virus had sparked a spate of deaths in Vietnam, and I had asked Professor Oxford to give me a tutorial on the ecology and virology of influenza before I headed to Hanoi to write a new feature about the virus for The Observer. Very quickly, our conversation turned to other notable outbreaks of infectious disease, including the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic.

This was for me the beginning of an obsession with the Spanish flu and other pandemic viruses that has led, by way of a doctorate and a research fellowship, to a deep engagement with the history of infectious diseases and pandemics.

Despite Professor Oxford’s concerns that H5N1 might combine with a strain of swine flu to create an “Armageddon virus,” the feared bird flu pandemic never materialized. Instead, he was accused of stoking a pandemic scare to boost spending on virus research. In 2009, the WHO found itself similarly in the dock when an outbreak of a novel swine flu virus triggered a worldwide pandemic alert, only for the illness to prove no more severe than a regular seasonal influenza. That is one reason why the WHO was so wary of designating Covid-19 a pandemic this time around, delaying the formal announcement until March 11.

Advertisement

How deadly the Covid-19 outbreak will prove to be, no one can yet say, but the echoes of 1918 are growing louder by the hour. For me, the sense that history may be on the verge of repeating came with those early images from Wuhan showing hastily constructed hospital “waiting rooms” filled with row after row of cubicles full of coronavirus patients. As the lockdown of Wuhan and other Chinese cities took effect, and the casualty count slowed, I held my breath. Perhaps China’s draconian quarantine measures would prevent a pandemic? Maybe we weren’t going to see a repeat of 1918, after all?

Then came the drama of the passengers trapped on cruise ship Diamond Princess. Confined to their cabins in Yokohama Harbor, most passengers thought it was simply a matter of sitting out the quarantine, after which they’d be free to resume their lives. Instead, a seventy-two-hour delay by Japanese officials in locking down the vessel after the notification of the first case turned the ship into a floating petri dish. The result was that by the time the quarantine was lifted, on February 19, two passengers were dead and six hundred and twenty-one had been infected.

A week later, the number of new cases outside China exceeded those inside China for the first time, and significant outbreaks were also being recorded in South Korea, Iran, and northern Italy. Then, without warning, at the end of February, several cases erupted at a nursing home in Seattle. As in 1918, the virus was now spreading under the radar, outside of known contact chains, making a pandemic all but inevitable.

Although we do not know where the 1918 pandemic started—one theory is it began in Haskell County, Kansas; another that it originated in northern France; yet another that it, too, came from China—the evidence suggests that, at first, the H1N1 Spanish flu virus also spread silently and stealthily around the globe. This was because, as with the present wave of Covid-19 infections, the initial illnesses were mild, with a mortality rate of around 0.5 to 1 percent that was too low to register against the background mortality from seasonal flu and unrelated respiratory illnesses. (Other factors in 1918 were the absence of sophisticated real-time epidemiological surveillance systems and the presence of a compliant press, rather than social media.)

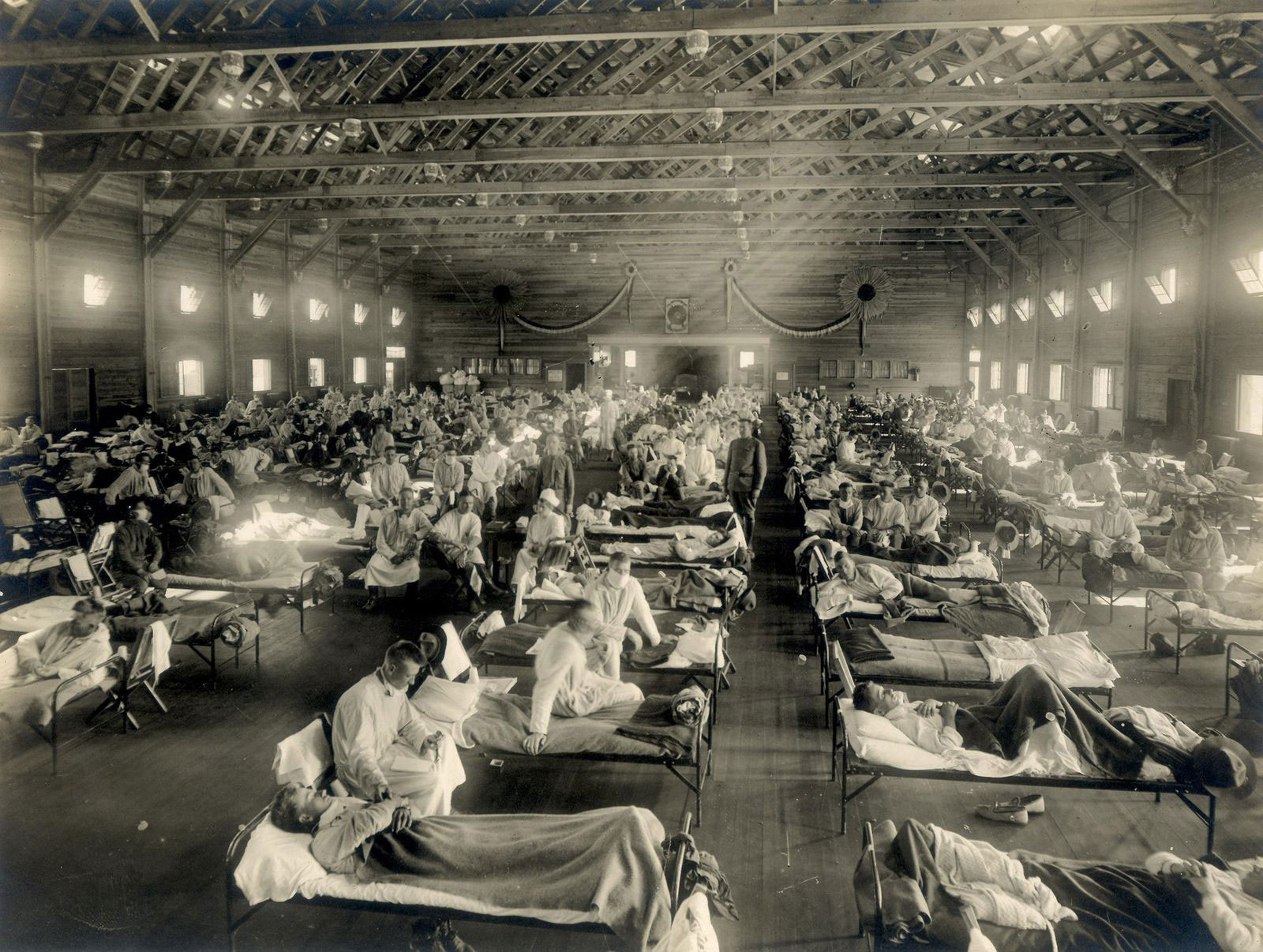

With hindsight, one of the missed epidemiological signals may have been an outbreak of a flu-like illness that occurred in March 1918 at Camp Funston, a US Army training camp in Kansas, where young recruits were being readied for passage to northern France and the rigors of trench warfare. The outbreak was explosive. Within a matter of days, some twelve hundred soldiers were on the sick list, forcing medical officers to requisition a large auditorium adjacent to the base hospital for the overflow. The vast majority of men suffered nothing worse than a three-day fever, but about a fifth of those hospitalized developed aggressive pneumonias, and by May, seventy-five of them had died.

Today, the photograph of more than two hundred soldiers laid out on cots in the emergency ward, is one of the best-known and most haunting images of the 1918 pandemic—though whether or not the image actually depicts an early wave of the Spanish flu is a matter hotly contested by historians. What is certain is that in May 1918, millions of Spaniards were suddenly stricken by a very similar disease, as were thousands of American and French troops in northern France.

By the early summer, large outbreaks marked by an unusual level of mortality in young adults—a hallmark of later waves of the pandemic—were also being reported in Copenhagen and other northern European cities. In Manchester, England, for instance, the local medical officer of health, James Niven, was so alarmed by the sudden sickness of a large number of schoolchildren that he hastily printed 35,000 handbills spelling out the dangers of influenza and giving strict instructions for the isolation of the sick.

However, it was the second wave of flu, in the fall of 1918, that brought home the humbling power of the virus. In London, for instance, deaths in October at the height of the killing wave were running at 4,500 a week, and there was panic buying at druggists. Health services across Britain were quickly overwhelmed. As one GP’s son from Lancashire recalled: “So many were ill that only the worst could be visited. People collapsed in their homes, in the streets and at work. Many never regained consciousness. All treatment was futile.”

Advertisement

As in the earlier spring wave, the worst-affected patients developed aggressive pneumonias in one or more lobes of their lungs. In some cases, these pneumonias were accompanied by a condition called heliotrope cyanosis that turned patients’ faces a deathly lavender color as they gasped for breath. The condition was nowhere more apparent than in September 1918 at Camp Devens, another large US Army camp at Ayer, Massachusetts. As at Camp Funston, so many soldiers were sickened that makeshift beds had to be installed in corridors and side rooms to take the overspill from the hospital.

“The faces soon wear a bluish cast,” recalled an Army medic who witnessed the death rattles of the worst cases. “A distressing cough brings up the bloodstained sputum. In the morning the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cord wood.”

*

To be sure, the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus is a very different pathogen to influenza. Although both spread via respiratory droplets in coughs and sneezes, coronaviruses do not transmit very efficiently as aerosols, as flu does. Indeed, SARS-CoV-2 is not thought to present a risk at distances further than six feet. Instead, the virus’s principal mode of spread appears to be through prolonged social contact, such as occurs in family groupings.

Another difference is that, unlike the Spanish flu, which had a notably high rate of mortality for adults between the ages of twenty and forty, SARS-CoV-2 is principally a risk to the elderly, those sixty and over, and people with underlying medical conditions. There is also no firm evidence, as yet, that children are a significant vector of infection, a crucial contrast with influenza and, indeed, the Spanish flu, which was seen to sicken children before adults.

On the debit side, there is mounting evidence that people who are symptom-free but infected may be capable of transmitting the virus. Worse, the average reproduction rate of SARS-CoV-2—that is, the number of people who will be infected by one infected person—is running at 2.2, which is markedly higher than the rate for Spanish flu, which was 1.8.

Another consideration is that in 1918 almost everyone had been exposed to some type of influenza before, meaning most people could count on a degree of immunity. The result was that the Spanish flu infected only a third of the world’s population. By contrast, no one has any immunity to the new coronavirus—hence the estimates that as much as 80 percent of the world’s population could have been infected by the time the pandemic will have run its course.

The greatest reason for concern, though, is that so far, SARS-CoV-2 appears to kill about 2 percent of confirmed cases. That is a very similar mortality rate to the Spanish flu.

But even that should not be a cause for panic or despair. One of the chief lessons of the 1918 pandemic is that cities such as St. Louis that acted early and decisively to contain the virus by banning large public gatherings, closing schools, and isolating ill or suspected case, fared notably better than cities such as Philadelphia that failed to take timely measures or did not sustain them. The problem, of course, is that such actions are hugely disruptive to the economy, a fact reflected in the reluctance of authorities to employ such measures except as a last resort.

That was before last week. Now that President Trump has reversed his previous position, rejoined evidence-based reality, and declared a national emergency, officials are having to contemplate even more decisive measures, such as calling on the Army Corps of Engineers to erect temporary medical shelters to cope with the expected influx of patients. This is not something we saw, outside of the US Army’s own camps, even in 1918.