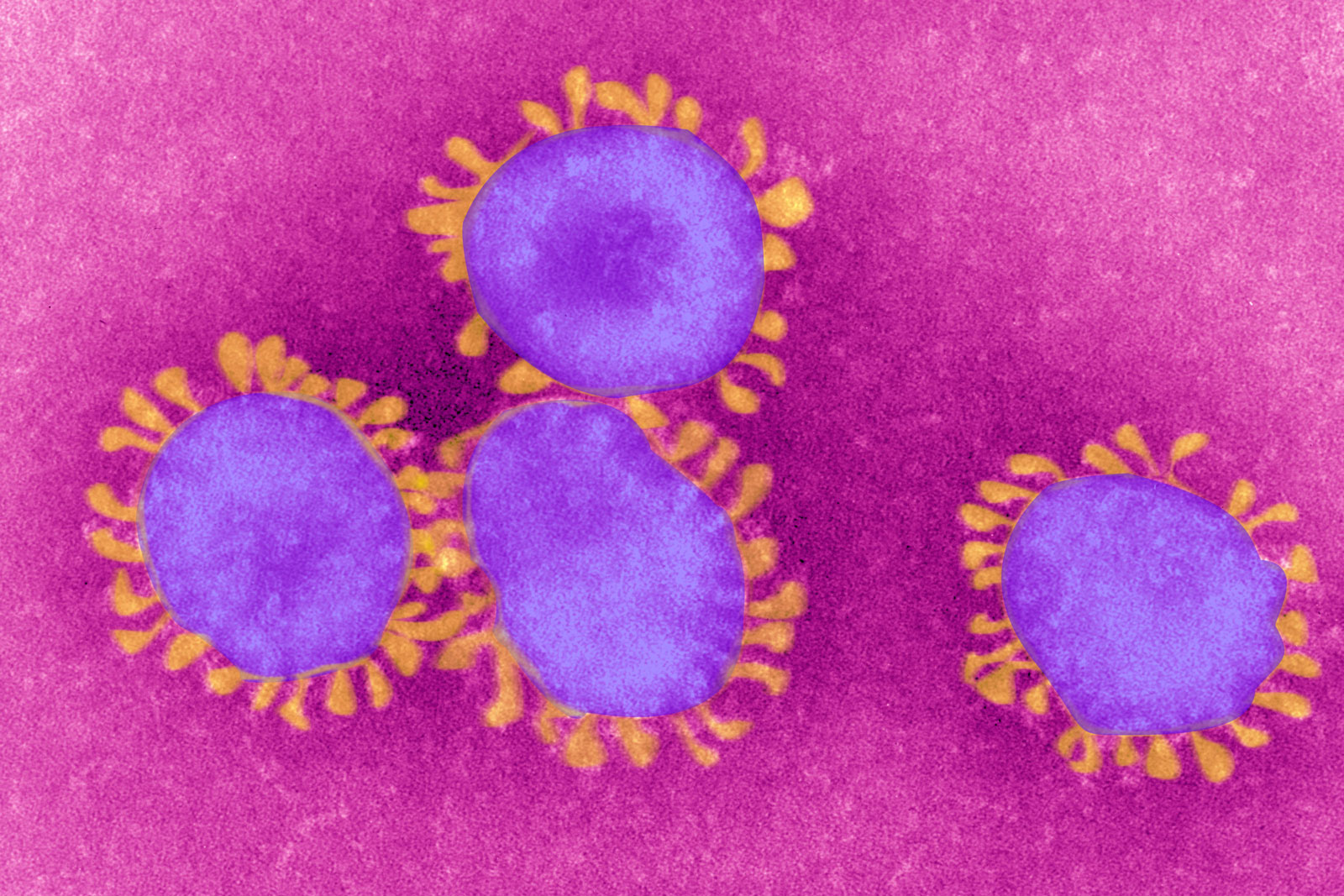

Aside from world war, nothing has the capacity to touch every citizen on the globe like a pandemic. This isn’t the first time the world has been gripped by a health crisis, and it won’t be the last. History has much to teach us about facing the spread of an invisible enemy. Why were warnings ignored? How are ecology and public health intertwined? Who stands to lose when a cure is inevitably found and the developed world moves on?

We’ve grappled with these questions in the Review before, through early accounts of the plague, histories of mosquitoes and rats, Philip Roth’s fictional account of polio season, and more. In the words of Eamon Duffy, writing about documents of the bubonic plague, “From the eye of the storm, it seemed possible that no one would be left to tell the tale.” But tell it they did.

Here is a list of plague and pandemic readings from our archives.

On the Brink of Oblivion

Eamon Duffy reviews three books on the Black Death in our May 23, 2002 issue.

“The late-medieval period is marked not by breakdown and despair, but by a remarkable resilience and adaptability. Confronted with the worst that nature, God, and the misdeeds of mankind could throw at them, medieval people adapted and survived.”

The Plague of Plagues

William H. McNeill reviews Robert S. Gottfried’s The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe in our July 21, 1983 issue.

“The last time human beings experienced a real epidemic was in 1918 and 1919 when a virulent form of influenza went literally around the world, and killed far more people than died in action in World War I. Few can now remember those days, and by a strange trick of memory those who lived through the flu epidemic seldom recalled the catastrophe afterward.”

On the Moral Brink

J.M. Coetzee reviews Philip Roth’s Nemesis in our October 28, 2010 issue.

“In a 2008 interview, Philip Roth mentioned that he had been rereading The Plague. Now he has published Nemesis, set in Newark in the polio summer of 1944 (19,000 cases nationwide), thereby placing himself in a line of writers who have used the plague condition to explore the resolve of human beings and the durability of their institutions under attack by an invisible, inscrutable, and deadly force. In this respect—as Defoe, Camus, and Roth are aware—the plague condition is simply a heightened state of the condition of being mortal.”

The Plagues Are Flying

Richard Horton reviews Mosquito: A Natural History of Our Most Persistent and Deadly Foe by Andrew Spielman and Michael D’Antonio for our August 9, 2001 issue.

“Search your house for the corpse of a common mosquito—Culex pipiens —and take a look at it under a microscope or a powerful hand lens. The image you will see is one of frightening beauty. The head is a compact black bullet from which emerge long thick spikes of hair, two segmented antennae, and clamp-like mandibles. A thin rod of a neck joins the head to the thorax, which is hunched and anchors the wings firmly in place. These wings are variegated and flecked with pigment, taking on the radiant transparency of monochrome stained glass. The six legs are long, bristled, and jointed. The mosquito’s back is arched into spring-like readiness; the entire body is shaped for attack.”

The White Plague

M.F. Perutz reviews three books on tuberculosis for our May 26 1994 issue, including Frank Ryan’s The Forgotten Plague: How the Battle Against Tuberculosis Was Won and Lost.

“[Frank Ryan] reminds us how precarious our lives used to be before the discovery of antibiotics, when a cut finger or a sore throat could be deadly, and he emphasizes that our battle against deadly bacteria can rarely be finally won, because natural selection leads to the multiplication of mutants which can overcome our best defenses.”

‘The First Great Pandemic in History’

Eamon Duffy reviews Lester K. Little’s Plague and the End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541–750 in our May 29, 2008 issue.

“From its first appearance in Egypt the chroniclers had commented on the devastating psychological effects of plague: dissolving social convention and established morality, numbing the feelings of survivors so that mothers might watch with passive indifference the sufferings of their children. In Britain, mass mortality on an unprecedented scale struck at the still-precarious Christianity of a nation only recently converted. The apparent powerlessness of the new religion in the face of this devastating visitation turned many back to the ancient gods.”

The Bright Side of the Plague

Joel E. Cohen reviews The Black Death and the Transformation of the West for our March 4, 1999 issue.

“A scarcity of workers following the drop in population created incentives for labor-saving technology, as the survivors among the poor insisted on higher wages. Guilds to which admission had previously been hereditary or strictly limited were forced to recruit more widely, from among the poor… Many bequests from wealthy people who had died made possible the creation of new national universities. These newly founded schools weakened the monopoly on education previously held by the ancient universities of Bologna and Paris. Because not enough teachers in these new universities knew Latin, the use of vernacular languages spread.”

Advertisement

The Disease of All Diseases

James Fenton in our December 1, 1994 issue.

“Then there was the intellectual hopelessness of the attempts to deal with plague. Some people resorted to isolation and austere living; some to singing and merry-making and all sorts of excess. The latter group we might say coped with the crisis by means of denial. They sought out houses where conversation was ‘restricted to subjects that were pleasant and entertaining,’ and these places became like common property. You went in and you helped yourself to whatever was on offer.”

How Animals May Cause the Next Big One

Florence Williams reviews David Quammen’s Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic in our April 25, 2013 issue.

“The mammalian placenta is made possible thanks to genes contributed by an ancient virus. Viral DNA is intertwined with ours and has been from our earliest beginnings. Viruses don’t just attack us; they are us.”

Infection: The Global Threat

Richard Horton reviews Laurie Garrett’s The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance and Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone in our April 6, 1995 issue.

“Here is one of the worst fears associated with the prospect of a plague: Any protection we might conceivably design depends on the foresight and commitment of politicians.”

City Folks

Sue Halpern reviews Robert Sullivan’s Rats: Observations on the History and Habitat of the City’s Most Unwanted Inhabitants in our May 13, 2004 issue.

“A plague scare, of course, is also a rat scare, and because rats are viscerally frightening to us, we may not recognize how much they and we share. Certainly we like the same food, though to be sure, the rat, whose jaws can exert seven thousand pounds of pressure per square inch, allowing it to snack on concrete and copper wire, has a more varied diet.”

Epidemic Man

Keith Thomas reviews William H. McNeill’s Plagues and Peoples in our September 30, 1976 issue.

“A disease like measles needs a population of nearly half a million before it can sustain itself. For this reason the migrant hunters of Paleolithic times seem to have been free from infectious diseases, or at least from those carried by microorganisms specifically adapted to the human species. Only when the rise of agriculture made possible the growth of cities did chains of continuing infection emerge.”

Time of Indifference

Helen Epstein reviews three books on global public health in our April 12, 2001 issue.

“Health care in developing countries is truly in chaos, but the evidence for this does not lie primarily in the flawed response to occasional outbreaks of Ebola and plague. What really testifies to the collapse of global public health are the weak responses to the millions of deaths from measles, malaria, diarrhea, malnutrition, pneumonia, AIDS, tuberculosis, and other preventable or curable diseases that occur every year in villages, urban squatter settlements, and refugee camps throughout the world, a disaster that often, with the exception of AIDS, goes unremarked by newspapers and television.”