On March 16, three days before I was due to give birth, French president Emmanuel Macron announced that, in response to the outbreak of Covid-19, residents had to stay confined to their homes. All non-essential stores would close. I had been following news of the novel virus from Paris. My father’s family is Chinese, and friends in China, including a girlfriend in Wuhan, had texted me about having to wear gloves and constantly sanitize their phones. An aunt who had been in China flew home to Texas and quarantined herself for two weeks, with no contact with her children or husband.

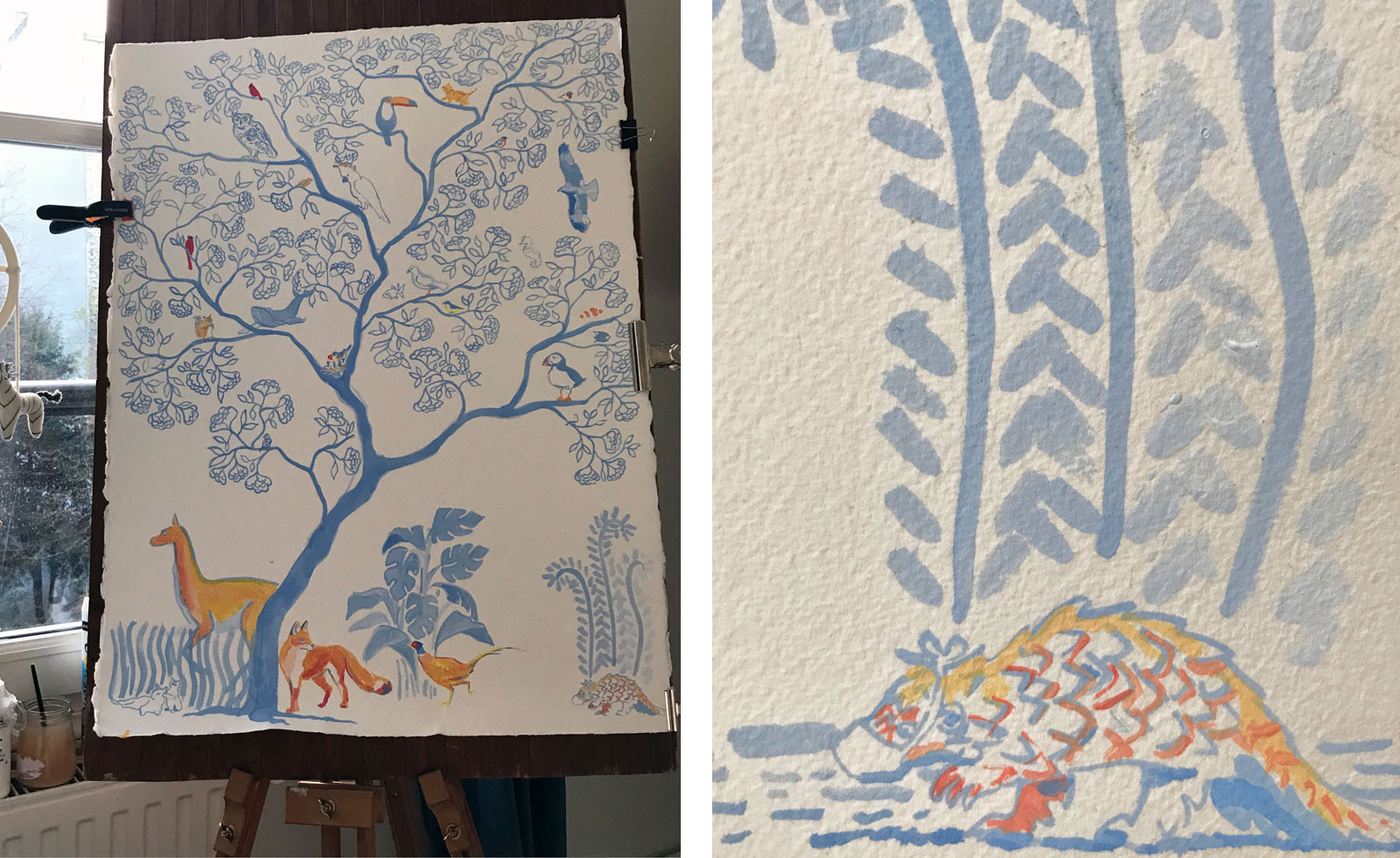

This was before any talk of travel bans or confinement in France, where we felt a general sense that the media may be blowing things out of proportion. I was nine months pregnant, and I figured I was effectively in quarantine already—confined by choice to our apartment, spending my days painting a mural for the baby’s room, folding the baby’s tiny outfits. It didn’t occur to me that the virus would affect anyone my age, let alone me. I was simply focused on the baby’s arrival.

But around the time Macron announced the confinement, I began to feel chills. I developed a cough, a runny nose, and a fever.

I didn’t want to see these symptoms for what they might be. Everything had gone smoothly during pregnancy; I’d spent the months formulating a vision of a normal, wonderful birth story. I was going to deliver at a private birthing clinic in the 15th arrondissement that had generous rooms and permitted stays of five to seven days, and where my husband’s family had been delivering their babies for generations. I was approaching my stay there like a planned peace. Now, I felt that I’d managed to fail as a mother before even giving birth. Had I been blinded? Had I been irresponsible?

I read the emerging studies from Wuhan that said the virus was not fatal to pregnant women and their babies. But nothing seemed certain. I was worried for my unborn child, and for myself: Would I be shunned from the clinic?I spoke to my obstetrician about my symptoms. He seemed to presume from this alone that I had the virus, and didn’t suggest a test. (They may not have been available.) He reassured me that I would be allowed to give birth at the clinic as planned, that there was a protocol in place for births that involved coronavirus infection. We agreed that I would come in for monitoring if the baby had not arrived by our due date, March 19. And if, after four days, the baby still had still not come, they would induce labor. This seemed normal enough. The OB told me to drink plenty of water and take paracetamol to bring down the fever. I told nobody else about my budding symptoms, but my husband and I did begin to sleep in separate rooms.

My husband is the youngest of four in a big traditional French family, the only son. Every summer, his three older sisters send their broods, darling and energetic children with names like Hadrien and Valentine, to bunk up at my in-laws’ house in the countryside, like a gorgeous Burgundy miniature of a happier Cider House Rules. He and I got married in an eleventh-century church nearby, a Romanesque masterpiece with UNESCO designation and five naves. We wanted to start a family quickly, but pregnancy didn’t happen right away.

After months of trying and inconclusive visits to several doctors, I began to see a Chinese acupuncturist, who told me that my body “is like winter, where no seed can grow.” She instructed me to cover up, and not to consume anything cold. She forbade me from walking around with wet hair. A few months later, I was pregnant.

I had nausea and fatigue, but I didn’t mind, these were part of the package. My pregnancy was a joy. The month I found out I was pregnant, we put our small, funky apartment on a hip street in the 10th arrondissement on the market and found a beautiful new home with space for a child’s room in the 7th. I was going to be a mother; the monotony of this staid, even fusty residential neighborhood wouldn’t bother me. Things felt, blissfully, as though they were falling into place. My mother-in-law gave us a bassinet that looked like a ruffled pram for a royal baby. She had spent months carefully reupholstering it herself. It has been in the family since 1903. Every child since my husband’s great-grandmother had slept in it.

Advertisement

The days leading up to birth were filled with excitement and anticipation. What sex would the baby be? Who would he or she look like? I spoke with my family back in New York constantly. They took every pause of a few hours in our group chat as a sign that I was going into labor.

Now, knowing I maybe, probably had the coronavirus, my peace was lost. I was afraid to tell my family back home, for fear of provoking anxiety or judgment. I worried about those I’d been around, people I might have infected. And I felt shame: toward the doctor, and already toward the baby.

By March 19, the due date, the baby had not come. Paracetamol had helped me keep down my fever and chills, but my cough and runny nose had gotten only worse. I felt like I had a bad flu. I went into the clinic for monitoring. Only I was allowed in the building, not my husband, who parked nearby. (Parking was now free in all of France, and the streets felt largely empty. Fortunate Parisians had escaped the city to their country homes.) He sat in the car so as not to be idling on the street; by then, anyone outdoors had to carry a signed form stating their state-approved reason for being so.

At the clinic, a man in a mask at the front desk held out antiseptic gel, gave me gloves and an N95 mask, then directed me to follow the “Parcours Covid-19,” or Covid-19 path, downstairs. Once in the observation room, a midwife in an aqua-blue hazmat suit came in to check on the baby by putting electrodes on my belly. The baby had not dropped and my cervix was not dilating. The midwife asked if I preferred to wait or wanted to go for it that day, and I said I’d rather start—unsure whether this meant induction or a Cesarean. I trusted my OB and the clinic. I just wanted to know if my husband would be able to be in the delivery room with me. The midwife said that he would probably not be able to join: too risky.

She left and my OB came in, confidently, wearing all the protective gear. My baby’s head was big, he said, and it was still sitting too high. Given this, and the rising rate of coronavirus infections, we agreed that I would have a Cesarean that afternoon.

Again, my main concern was to have my husband be in the delivery room, and my OB said he didn’t see why he shouldn’t be there so long as he didn’t touch anything. He said there were a few nurses in the delivery room who were against it, but not to worry: he would continue to argue in my favor. Grateful, I called my husband to hurry in.

Then they whisked me away— still wearing a patient gown, still in gloves and a mask—to a high-ceilinged room, where a nurse and an anesthesiologist were waiting. As the young nurse rolled me onto a gurney, she griped about having to wear the masks that trap heat.

“On n’est pas habillés comme ça normalement,” she said, seeming almost embarrassed. She may have felt sheepish, in fact, about having to tell people not to touch me as I was wheeled to different parts of the clinic. But once we were in the OR, she asked about my symptoms as she put in an IV at my right wrist. She and the anesthesiologist were discussing the virus casually, what they’d heard from other hospitals. They asked if my husband had had symptoms, too, if we’d experienced diarrhea.

As things got moving, I checked the clock nervously: it was after 4 o’clock and my husband was still not there. My only thought was whether my husband would be able to come to the delivery room. As they began preparing me for the incision, laying me out on the table, my husband was still not there. I began to lose sensation in my legs from the epidural injection, and I asked again where he was. The nice young nurse told me that he probably couldn’t make it because of the Covid-19 protocol.

They erected a big blue curtain at the level of my chest. There must have been four or five other people in the room. My OB came in. Somewhat frantically, I asked where my husband was, and someone said he was in the clinic and that he would be here shortly. I could hear my OB and someone else in the room arguing about my husband’s entering. I felt panic and, at the same time, social discomfort—as if I was eavesdropping on a conversation about me that I wasn’t supposed to hear, and I was embarrassed to be creating conflict between colleagues.

Advertisement

Just then, I saw a familiar pair of eyes rushing toward me, covered in scrubs from head to toe, wearing a shower cap, mask, and gloves. He knelt down next to me, holding my head and my left hand, telling me he was so proud of me. I started to cry. It was 4:40 PM.

I could not feel anything from the chest down. A blue curtain shielded my lower half. My OB announced that the birth would be “dans une minute,” and a few moments later, I heard a baby cry, my baby. The sheet was lowered, and my husband tilted my head up to help me see the crying baby being lifted from my abdomen. It was bigger than I expected, with a full head of dark hair. “C’est une fille, c’est une fille!” my husband cried.

We told the hospital staff that her name would be Claire. They said I could touch her, and I caressed her dark hair with my gloved hands. They finished up with me on the delivery table. There were so many people tending to me, and I knew that I was putting all the nurses, the midwives, the doctors at risk. Their families, too, and their other patients. Because of the suspicion that I might have the virus, my husband was whisked out with Claire to a room near the OR, where they attached electrodes to her chest. When I joined them, the three of us were moved into isolation. We were not permitted to leave our room.

*

Some hours later, I began to feel excruciating pain in my abdomen. They told me this was normal after a C-section—the constant French ring of “c’est normal.” Because of my coronavirus symptoms, I was not allowed anti-inflammatory medicine (which my doctor said might be dangerous for Covid-19 patients—though other medical professionals dispute this), so I was given paracetamol and a dose of morphine. At around 1 AM, I started throwing up the water I’d been trying to sip. My temperature dropped, though I felt extremely hot. The pain from my C-section incision seemed to climb all the way up my chest to my collarbones.

An hour later, I started shaking and coughing with pain. The midwife said this kind of writhing was normal because my uterus was contracting, but she called an anesthesiologist to give me something for the pain. When he came in, he began kneading my stomach, which sent me into worse convulsions. They seemed to conclude my digestive tract was still adjusting. He left.

The next morning, at last, my OB came. When he lifted my gown to see my belly swollen and hard to the touch, he asked for a sonogram machine. They weren’t available in our quarter of isolation, and so we had to wait. When it finally arrived, it seemed that I had hemorrhaged after the C-section and that my abdominal cavity (my peritoneum—the area around my organs—a new word I learned in both languages) was filled with blood. I was to go to surgery immediately.

It was only before this second surgery that I was given a Covid-19 test, along with several other blood samples they needed. They stuck the pipette-like device far up my nose. The nurse apologized for the discomfort, but compared to the shooting pain pulsing through my body, it was nothing.

I was wheeled downstairs to the same operating room. This time, nobody made conversation. They put an oxygen mask over my face. For a few moments I was still conscious, I just couldn’t speak or move.

When I came to, there were many people in the room. The same young nurse from the birth gave me oxygen through my nose and transfused two bags of blood. I had lost about three pints of blood—the amount in a big bottle of Evian, they said. The anesthesiologist who had come in the night provided a dose of another painkiller that was fed to me in an IV: ketamine. Finally, for a few hours, I felt some relief.

It was as I was coming down from the ketamine that the young nurse told me I had tested positive for Covid-19.

*

When they wheeled me back to the room I’d left seven hours earlier, I found my husband waiting for me with Claire in his arms. He had been feeding and caring for her alone. Typically, recovering mothers have the option of placing their baby in the nursery, so that they can get some sleep. But our Claire was the first coronavirus baby at the facility, so she had nowhere to go: she might risk other babies’ health, and there were not enough nurses with protective equipment to take care of her.

Because I had the virus, my husband most likely did, too—though there were not enough testing kits available to establish that. That afternoon, the clinic had kicked all of the fathers out of the clinic as a precaution. But my husband refused to leave, and the situation was exceptional enough that they let him stay.

The days that followed went by in a blur. My abdomen was swollen and covered in livid bruises from the C-section and the subsequent surgery. I would vomit and bleed on myself in bed while my milk was coming in. Several attempts to get up to go to the bathroom ended in my being stuck on the toilet, usually in tears.

Because Claire and I were the first corona maman et fille at the clinic, the clinic’s staff had not fully followed the Covid-19 protocol. They were still learning it. Things had been haphazard. At one point, I’d taken an elevator while on the gurney. I learned later that they’d sent someone in to disinfect it after I was wheeled off. I felt like a burden. Had I not started to show symptoms, I could have infected the entire ward.

I do not know if the hemorrhage was related to the virus. A doctor friend told me she heard that there were more hemorrhages after C-sections in infected mothers. I do not blame the doctors or nurses at the clinic. How could I? They did everything they could in the circumstances, and for my full week of recovery at the clinic. They did not know the level of pain I was experiencing. But without the distraction of the coronavirus, I have to believe that the rare complication after my C-section might have been spotted sooner, and the internal bleeding could have been stopped earlier.

I don’t expect I’ll get a test to know when I’m no longer infected, let alone two. As for Claire, no one suggested testing her—the doctors told me there was no risk for babies, that she would get my antibodies through breastmilk (this came before the devastating infant deaths in Illinois and Connecticut). I know how lucky I am to be OK, and possibly to have developed immunity. So little is known about this virus, which is now tearing through the town where I grew up, which borders New Rochelle in Westchester County. Paris, the city of my adulthood, remains in lockdown. I don’t know when we’ll be able to see our pediatrician, or introduce Claire to her paternal grandparents, who stood outside their apartment, ten minutes from ours, in masks, and waved as we drove their car home from the hospital in our own masks. My parents’ flight to Paris was canceled, of course. We use FaceTime and Houseparty to introduce her to her family in New York.

Our midwife, Isabelle, came to our house this week to check on me and Claire, changing into her hazmat gear outside the door. We were worried that our new neighbors would see. I still feel the shame of being infected—though I have no idea how I got the virus, and probably never will.

When I was pregnant, my friend Amy, whom I met while living in Beijing after college, and who had texted from Wuhan, gave me a book about zuo yue zi, the Chinese practice of “sitting the month” after delivery. All of a sudden, I am unintentionally doing zuo yue zi. My French husband prepares me Chinese dishes like chicken, red date, and ginger soup with goji berries, or egg-drop soup with liver and greens—traditional postpartum meals to nourish me, as I learn to nurse our daughter.