I had recently moved to New York City when Occupy Wall Street erupted in lower Manhattan. I remember walking south to Zuccotti Park from the West 12th Street apartment where I was staying temporarily—home for many decades to my cousin Tony, a veteran writer for Sesame Street, and his wife, Phyllis—while their executor prepared the apartment to be sold. Looking through Tony and Phyllis’s things, I came across a photograph of the Twin Towers, taken from their living room window. A decade after the towers had fallen, I looked down at the photograph, then up again at the skyline where, minutes before, I hadn’t felt their absence.

In Our Voices, Our Streets: American Protests 2001–2011, Kevin Bubriski documents the first decade of the new millennium with portraits of dissent, from demonstrations against George W. Bush’s inauguration in 2001—and the gatherings at ground zero and anti-war marches that followed—to Occupy Wall Street in 2011. The images in this book, the most recent of which were taken only five years before the 2016 election, are a kind of time capsule. Like many rediscoveries, they offer a sense of continuity while also revealing the distance between now and then. More than one slogan on the homemade protest signs Bubriski captured—“Republicans for a Sensible Foreign Policy”—is unquestionably of another era; 2001’s “Democracy Dies Today” sounds almost quaint.

And as many of us have been sheltering in place for weeks now, it’s impossible not to recognize our passage into an unforeseen and entirely unprecedented era. Large events and gatherings are currently outlawed across the country. There’s tension in the fact that, right now, taking action for the sake of all requires that we stay at home—that we rally while physically apart.

Worries about how our social fabric and devastated economy will fare from months of social distancing are eclipsed only by fury and fear—observing the total ineptitude and selfishness of our president and his allies, bracing ourselves for escalating chaos and authoritarianism as we approach the 2020 election. Those of us who are not essential workers, doing what we can to take care of ourselves and others from home, are faced with the task of organizing remotely, joining together in arenas other than the street. (Essential workers, meanwhile, have been striking for better and safer working conditions.) In addition to everything else it touches, Covid-19 may forever change the way Americans participate in political life.

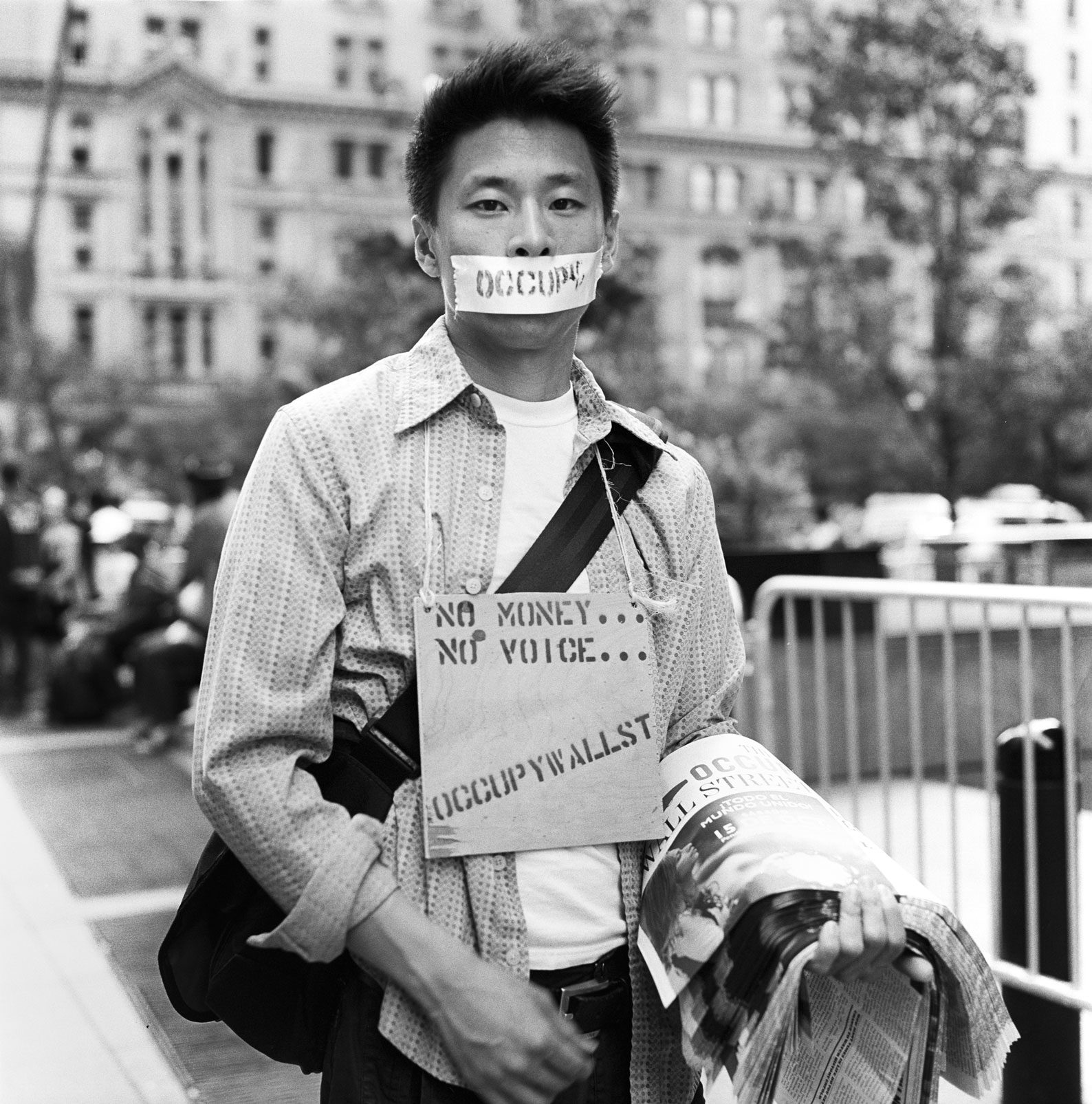

With New York presently the country’s epicenter of the pandemic, Occupy Wall Street may feel particularly remote—perhaps in part because its influence has been so thoroughly metabolized by the contemporary left. It’s difficult to remember a time when the major ideas of the movement that began in a public park in Manhattan’s financial district, organized to unite a “99 percent” around issues like unaffordable health care, compromised democracy, unrelenting student debt, and other effects of neoliberal global capitalism, weren’t taken for granted. In one of Bubriski’s photographs, a twenty-something holds a sign itemizing a “Wall Street ‘To Do’ List,” which includes buying the presidency and the Supreme Court and owning all media; in another photo from Zuccotti Park, a young man with an Afro-mohawk and a bandana looks on with a slight smile, while three of his fingers rest across his neck as if lazily taking his own pulse.

I grew up with Bubriski’s images—I consider him an uncle. His photographs of Nepal, Morocco, Brazil, and Syria hang in my parents’ house; the gesture of two holy men bending in a kiss, the impossible blues of Marrakech alleyways, are as familiar as a family portrait or the faded wallpaper of my childhood. But the very American scenes of Our Voices, Our Streets were new to me, and familiar in a different way. The images invoke atrocities around which the people pictured rally in dissent—war, corruption, injustice—but these events are not themselves the subjects of the photographs.

Photography criticism has, understandably, spent more time on images of atrocity than on images of the movements organized against it. But the terms of debate might be similar. To borrow Susan Sontag’s famous critique of war photography—that an image of protest, like that of suffering, has the capacity to move us (people are in the streets, I should join them!) or to inure us (people are already in the streets, why join them?)—exemplifies the predicament particular to the artform, the dual responsibility of documentation, of “bearing witness,” and of having an aesthetic, as art.

Advertisement

That photographs necessarily have a perspective is by now conventional wisdom, and Bubriski’s point of view distinctively emphasizes the individuals who make up a crowd. But considering how continuously media are evolving, the effect that images have on our perceptions and habits seems to demand frequent reassessment. In our era of smartphones and social media (Instagram launched just a year before Occupy), of Black Lives Matter and the Climate Strike, of the Mueller Report, impeachment and acquittal, and now of the global pandemic, Our Voices, Our Streets puts a face—many different, striking faces—to the notable evolution of photography over the last twenty years.

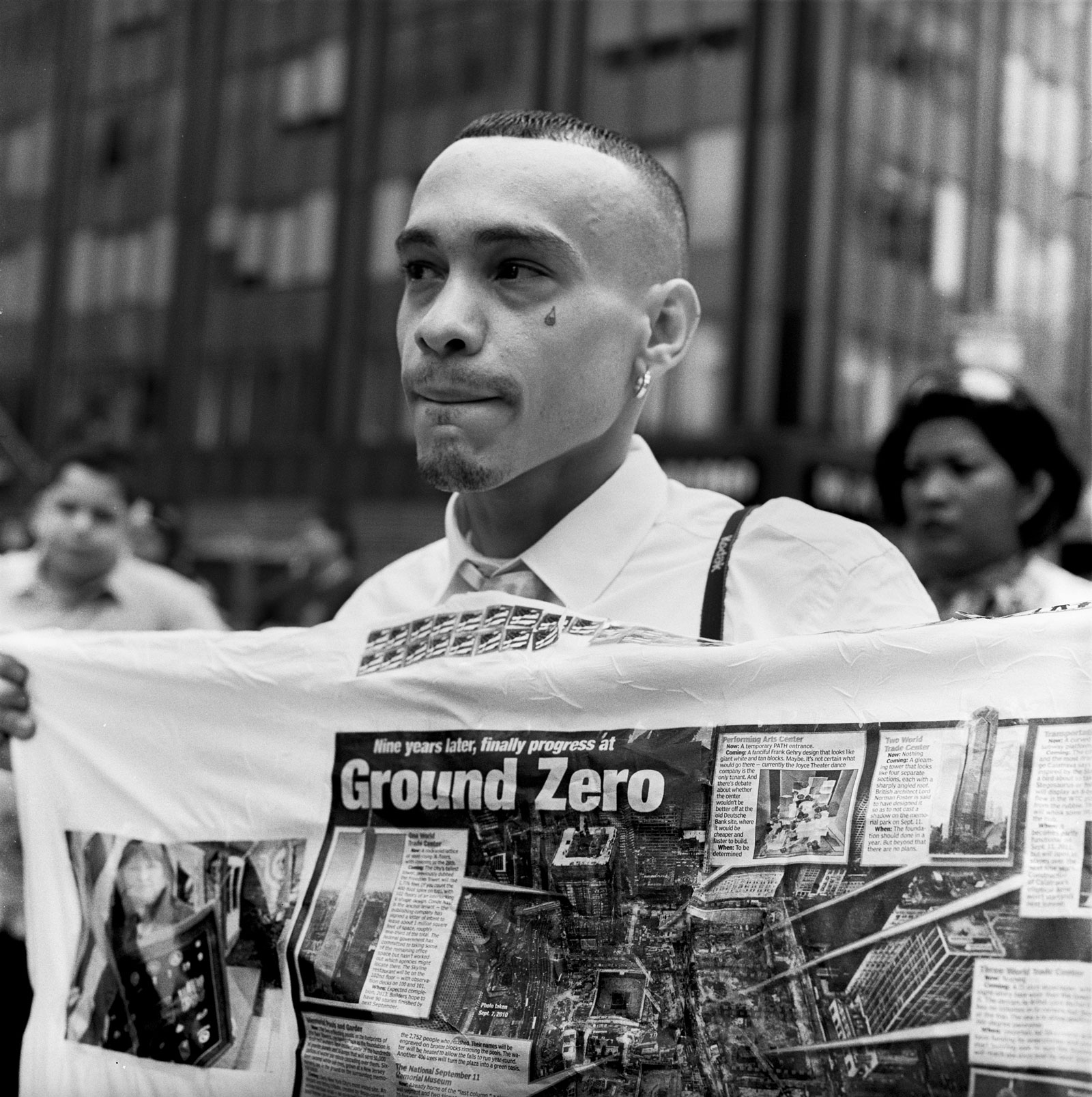

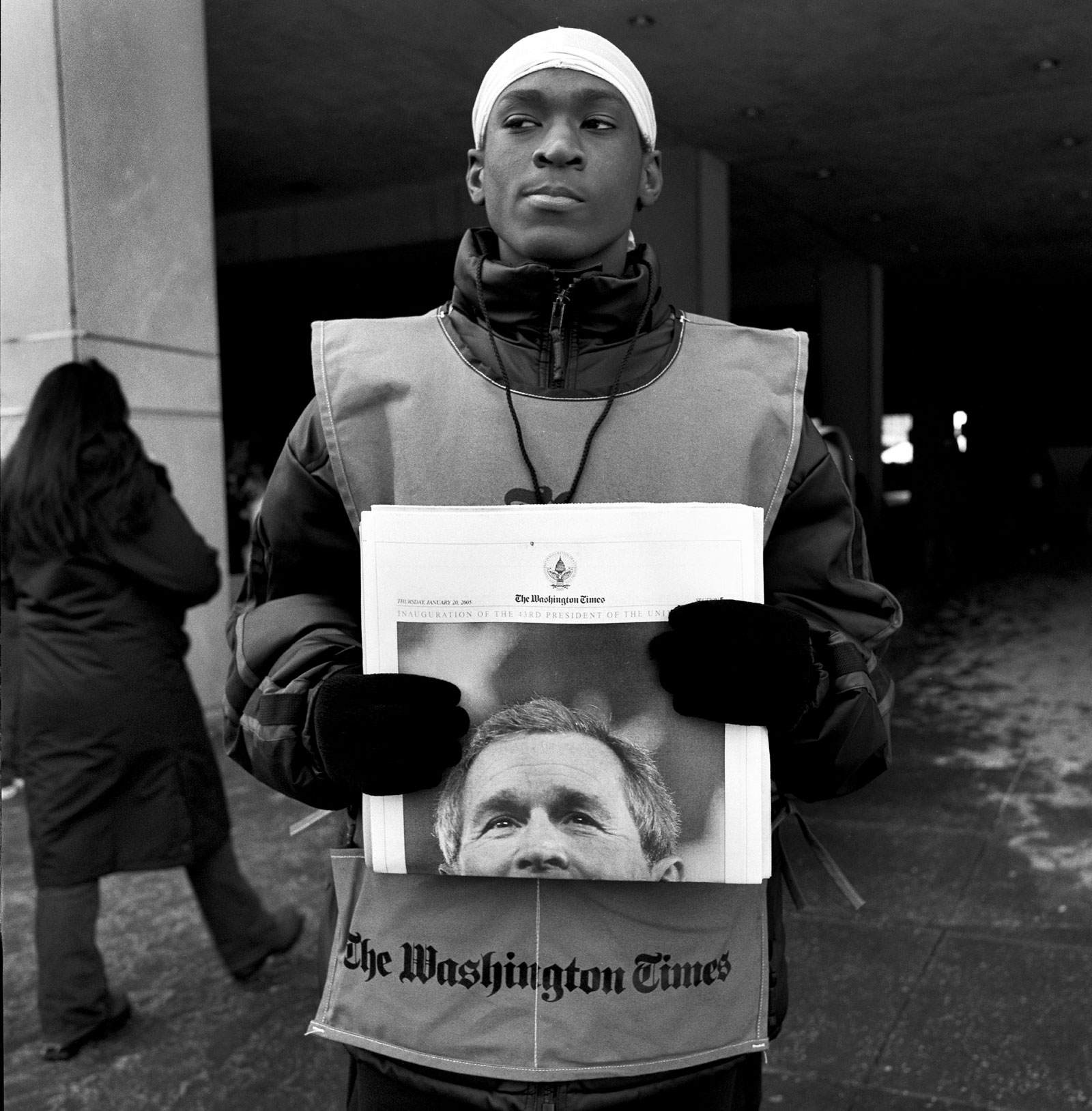

Some faces are particularly memorable: an older white woman holds a sign reading “President Bush, You Killed My Son” at an anti-war march at the 2004 Republican National Convention, her face mostly obscured by a hat and sunglasses, her mouth set as a man stoops down to speak to her. A black teenager wearing a Washington Times smock and holding the paper announcing Bush’s second inauguration delivers a side-eye; the gaze of the president floats, disembodied and smug, his face folded just below the nose. A reverent trinity of profiles, two men in baseball caps and a woman with platinum hair, all face the same way at the World Trade Center site on the tenth anniversary of September 11.

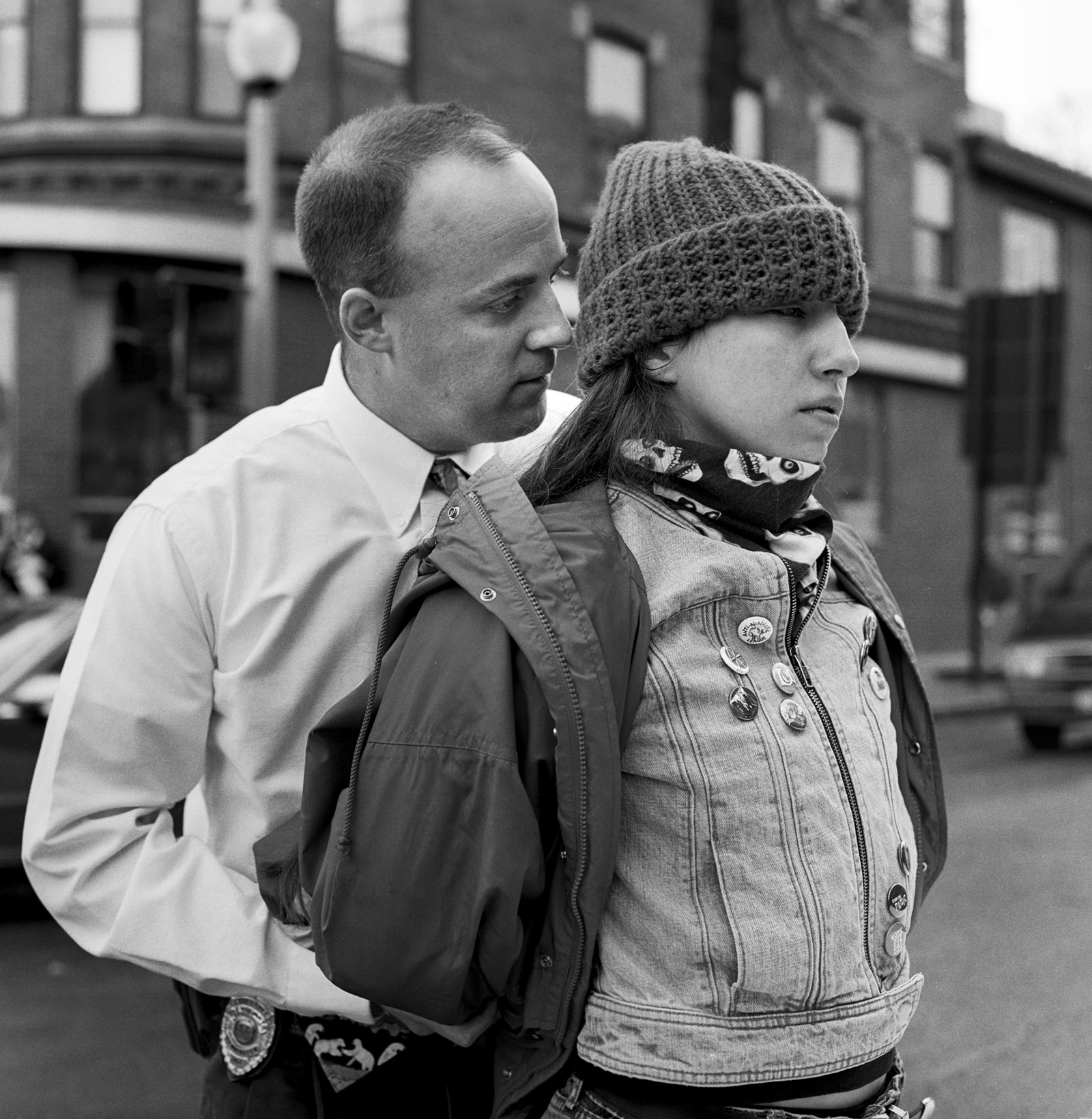

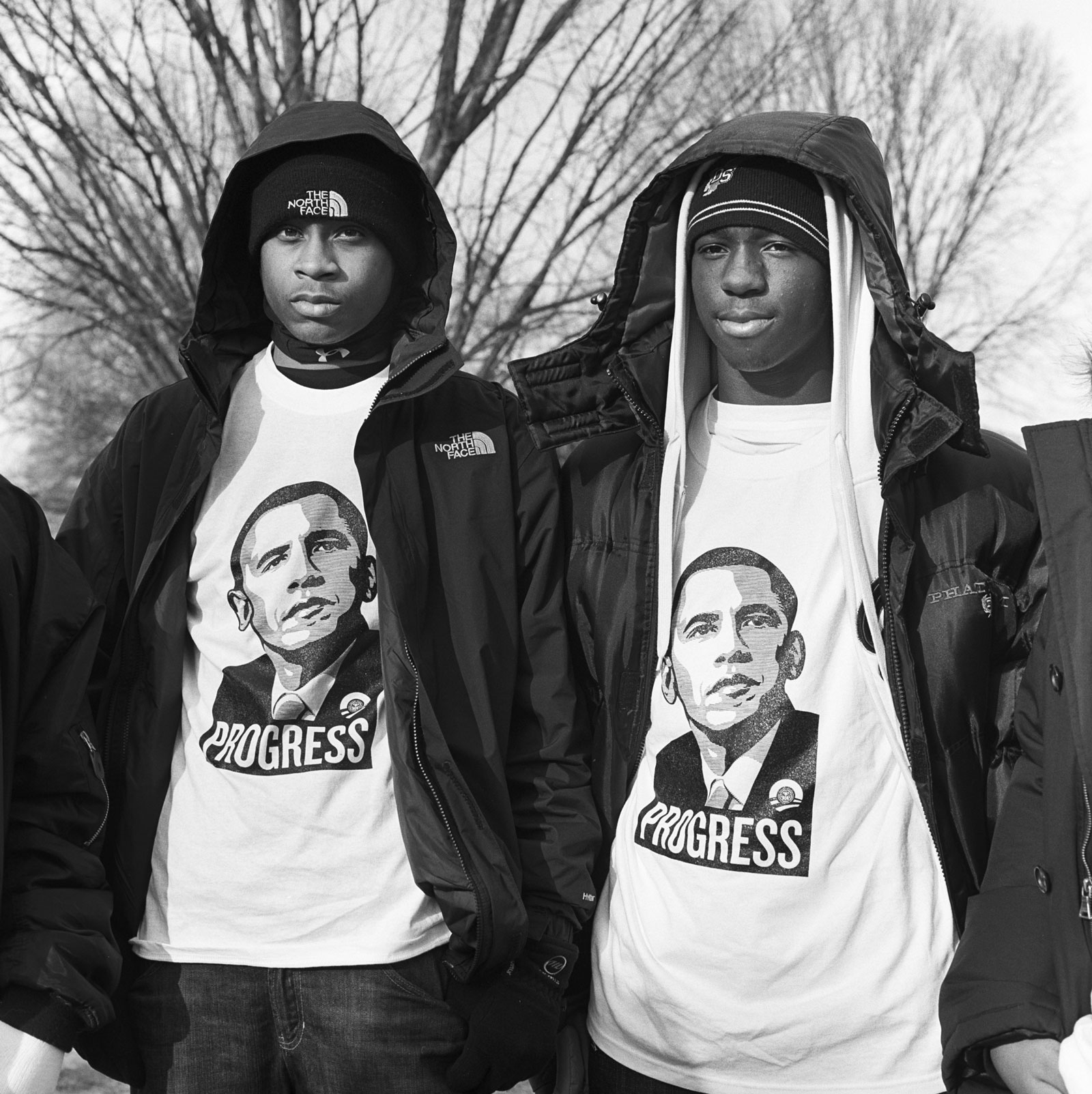

Moments of determination, fury, and grief are complemented by those of celebration and commemoration, like the thrilling hope captured at Obama’s 2008 inauguration, or the pensive pride at Bennington’s Veterans Day Parade. Police officers point and wield their batons. Counter-protesters hold their own signs and views. Bubriski’s portraits include people with different, opposing politics. There is a funeral for one Iraq War soldier and a welcoming parade for another.

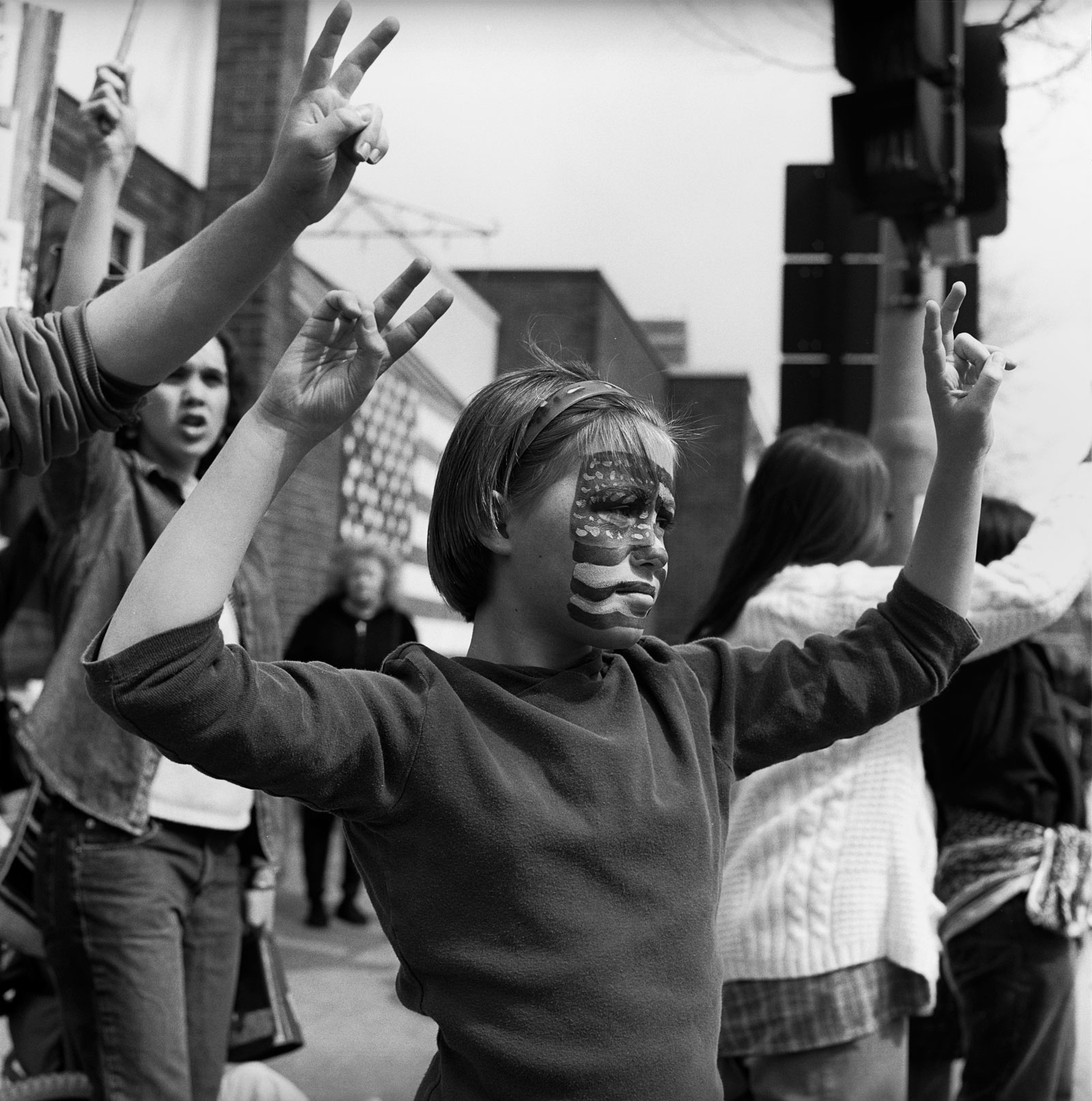

And though these images are of specific times and places, all protest photographs seem to refer to one another, despite the differences in their causes, fashions, slogans, and aesthetics. A little girl at a peace march in Bennington, her face painted over with an American flag, her hands raised in peace signs, makes me think of images of Vietnam War protests. I’m reminded, too, of the young man at a Selma to Montgomery march, his face painted white save for the word “VOTE,” which stands out across his forehead, the American flag behind him, photographed in 1965 by Bruce Davidson. Another of Bubriski’s images—three black men in exquisite composition in Washington, D.C., stylish in all-black with leather, berets, and sunglasses—recalls portraits of the Black Panthers by Stephen Shames. Bubriski’s photos from a demonstration in solidarity with Palestinian rights, perhaps the largest ever such in the US as of 2002, bring to mind the history and continuation of this long conflict. Our Voices, Our Streets reminds us how far back our present political ideals go, and how far they may yet have to travel.

America since its founding has been a place of extreme tension, violence, and turmoil. Each decade inherits the legacy of those that preceded it, and while the future looks no less extreme, we’ve so far continued to gather together. Recently, young people are leading movements—from the activists who founded Black Lives Matter in 2013 to the 2018 student-led March for Our Lives against gun violence; from the youth-driven proliferation of socialist ideas in politics to the organizing of fourteen-year-old clean-water activist Autumn Peltier and sixteen-year-old climate activists Isra Hirsi and Greta Thunberg. As their voices and others’ are heard, and as the contours of our current crisis shift and evolve, and we adapt, eventually taking to the streets once more, I imagine Bubriski there, making images to help us remember as clearly as possible this next chapter in American history.

Our Voices, Our Streets: American Protests 2001–2011 is published by powerHouse books.