The 2020 Census count, which is vital to our politics and economy, is reeling from the coronavirus crisis. Taking safety precautions to limit social contact, the Census Bureau has already suspended its crucial field operations. The Trump administration, wavering from day to day over its response to the pandemic, has further hamstrung the count.

As the Covid-19 crisis worsens, the 2020 Census is facing a triple bind: ensuring the safety of its national staff, including its legions of doorknockers; not endangering the general public; and all the while meeting its constitutional responsibility to deliver an accurate population count to President Trump by December 31. With the obstacles presented by the pandemic, and a truculent White House that has been sabotaging its work from the jump, the Census Bureau is scrambling to count each person and in the right place. And Monday, the Trump administration itself conceded the difficulties by asking Congress to delay the Census Bureau’s field operations until June 1, to now complete the count by October 31.

Beginning in June, then, census takers are expected to visit households around the country that have not responded to their questionnaires, as well as transitory locations like campgrounds, RV parks, marinas, and hotels. As of January, the bureau planned for at least 500,000 temporary, part-time, or full-time census takers for its field operations. As it monitors the pandemic crisis, the bureau will adjust its census-taker and survey operations as necessary, in line with federal, state, and local health precautions.

The fallout from a miscount will not be as grave as the human death toll now afflicting the country, but an inaccurate survey has very serious consequences: Census 2020 data will be used to calibrate the distribution of political representation and federal resources until the next count, a decade later, in 2030. Each state’s allotment of representatives to Congress, its Electoral College votes, and its federal financial resources are calculated by the latest count. Not only are the Census data used to redraw congressional and local voting districts, in order that the districts are representative and not discriminatory, but these data are also used to challenge unfair redistricting by watchdogs.

According to John H. Thompson, who served as the director of the Census Bureau from 2013 to 2017, nonwhite and Hispanic populations have been historically harder to count, for a host of compound reasons. “African Americans have undercounts that are higher than white non-Hispanics, Hispanics have higher undercounts, Asians have higher undercounts,” he told me in a phone interview. Thompson elaborated that populations that may fear government or immigration authorities, that are mobile, that have tenuous attachments to housing units, that have low levels of formal education, and that rent and do not own their homes, are historically harder to count.

Moreover, a big hurdle stands not only for the millions of Americans who cannot functionally read or write, but also for those who have challenging living situations, such as a landlord who may not want to include them on the census form for that household (commonly because of the landlord’s illegal renting practices). With Covid-19 infections raging nationally, evacuated, stricken, and precarious communities also remain most at risk for an undercount: dense locales, low-income neighborhoods, immigrants, the elderly, and those living in, or evacuating, group-based quarters, including nursing homes, campuses, and shelters.

A mitigating factor—for some—is that the bureau, for the first time ever, is encouraging people to respond online. Then again, the pandemic itself has harshly exposed existing inequities in Internet connectivity, especially for low-income urban and remote rural communities. Those households that do not reply to the bureau’s initial questionnaire digitally, by phone, or through mail, are expected to receive another paper questionnaire between April 8 and April 16. Earlier this year, the bureau projected that in-person census takers may be responsible for recording up to 40 percent of the count. The question that then arises is whether the bureau’s non-response follow-up efforts, tentatively scheduled to begin in May, can effectively work. If the Trump administration’s haphazard Covid-19 response further hampers the states’ capacity to tackle the pandemic, how will the bureau conduct its vast follow-up, in-person field operation safely amid a continuing crisis?

*

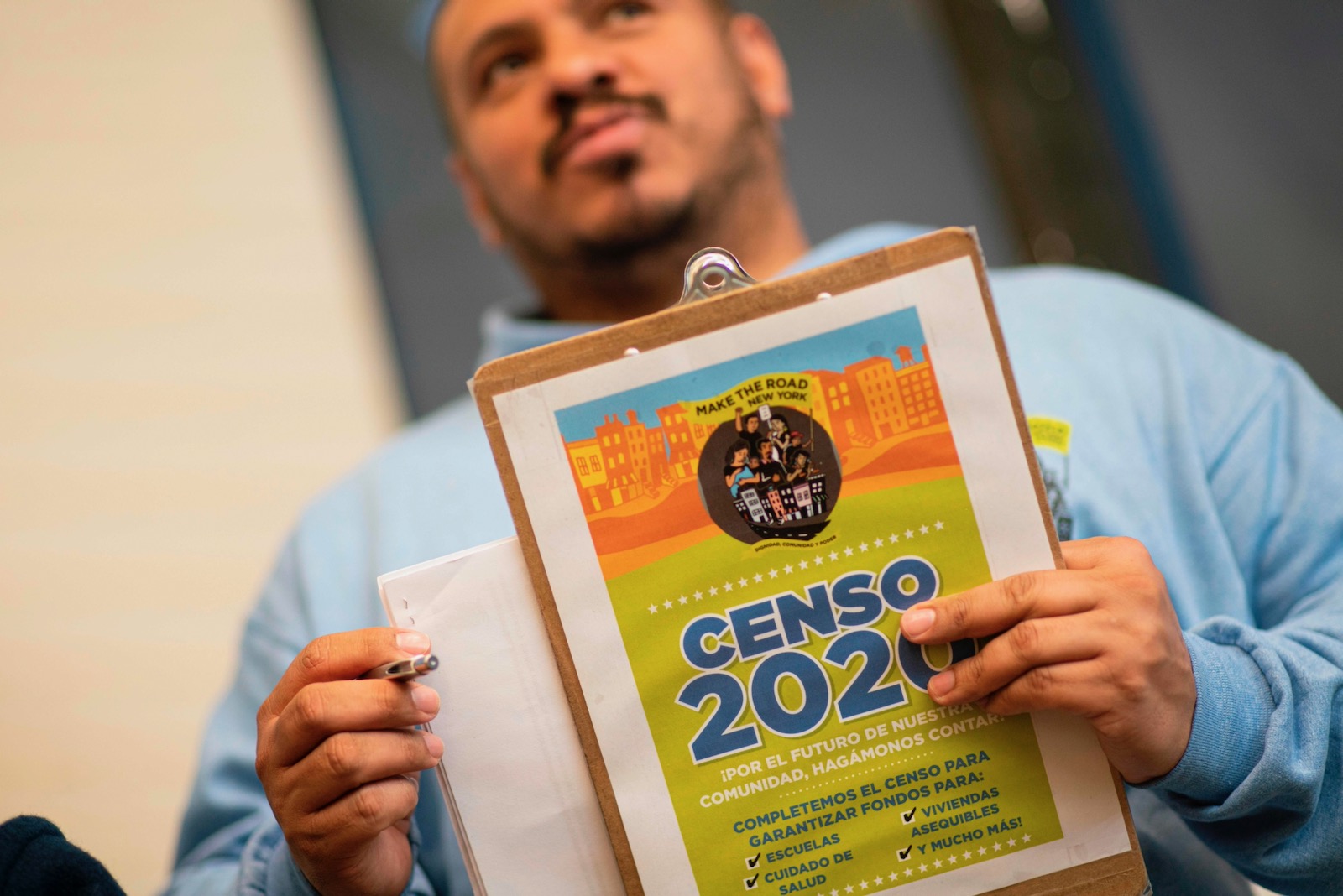

The Census Bureau has partnered with more than 300,000 institutions to assist its count, such as the National Conference of State Legislators, the National Association of Latino Elected Officials, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, and the Urban League. These groups have helped the bureau’s work by means of promotional campaigns, in-person outreach, and the hosting of local events, including in churches, community centers, and medical clinics.

Advertisement

Timing matters to an accurate count, according to Thompson, the former director. “The further you get from numerating people closer to the Census date, which is April 1, the harder it gets to get accurate results,” he said. “So, for example, they’re not counting the homeless population right now, and when they eventually do count them, the population may be different and in different locations from where it was on April 1.”

At this point during the last count, in April 2010, many more households, as a percentage of the population, had responded to their Census forms compared to April 2020. But evaluating the response rates between then and now with precision is difficult, because the record-taking methods between the counts is different: 2010 requested paper-only and limited phone response, whereas this year encourages digital response. Even so, early research coming from the City University of New York Mapping Service indicates that nationwide self-response rates for the 2020 count significantly lag self-response rates at the same time period in 2010. This fall-off, however imprecisely known, deeply concerns advocates about the progress of self-response rates generally and among hard-to-count communities in particular.

The Latino Community Foundation, a philanthropic collective of Latino organizations, is the contractor that California has selected to conduct census education among the state’s Latino communities. The foundation had achieved solid results leading up to the coronavirus crisis, working with trusted messengers in its outreach efforts. The group relied on local ethnic radio stations, community health clinics, Hispanic chambers of commerce, and youth-serving grassroots organizations, said LCF’s policy director, Christian Arana. It even launched a Census-inspired lottery game called “Censotería.”

Grassroots groups working toward a complete and accurate count are describing serious challenges to programs assisting their communities in the face of the coronavirus. One such group that has been toiling for years leading up to the 2020 count is the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA), a national nonprofit immigrant-rights organization based in California. CHIRLA launched its “Contamos Contigo” campaign roughly a year ago, on the eve of the Supreme Court hearing on the citizenship question. The campaign worked to educate 2.7 million people about the Census in hardest-to-count households—Latino residents, immigrants, refugees, and non-fluent English speakers—through forums, workshops, and demonstrations that have been held at schools, library branches, and resource fairs. This spring might otherwise have delivered a positive culmination of CHIRLA’s year-long planning, but the group now finds itself trying to have these conversations with immigrants in the middle of a global pandemic, quarantines and lockdowns, and an instant recession.

“People have a lot on their plates right now, particularly immigrant communities, many of whom are being considered essential workers during this time,” Esperanza Guevara, the census campaign manager for CHIRLA, told me by email. “The challenge is not only to connect with someone who is experiencing additional layers of instability in their lives, but then transitioning the conversation into troubleshooting the Census with them. We’re working with folks that may not have access to the Internet at this time, or may not have the literacy skills to fill out a form on their own or to do so remotely.”

From an operations standpoint, it is taking a lot of work for grassroots groups to switch their in-person assistance and canvassing teams to working by phone and digitally. In states that are under stay-at-home orders, local activists have been working from home themselves for the past few weeks, to adjust their in-person outreach to the new circumstances.

CHIRLA has switched its census outreach and assistance campaign to call center teams that attempt to do the same work through remote phone-banking. The group is monitoring regions with the lowest response rates and making calls to Latinos, “low-propensity” voters, and individuals whom the group has assisted in the past through its extensive community education network, including civic, legal service, and medical programs. It is also continuing to operate its immigrant assistance hotline.

“Luckily, our team is made up of a lot of badass women,” says Guevera, who is under stay-at-home orders herself. “These women have been putting in the hours, supervising phone-bankers by Zoom, conducting remote trainings, and providing technical support or troubleshooting issues with phone-bankers.”

Some grassroots immigrant groups report that their community members have had a hard time connecting with the national bureau’s hotline operators, and when the members do connect with bureau staff, these immigrant callers report that Census operators have been rude or impatient with them. The groups maintain that the bureau seems to have fewer phone operators due to the impact that coronavirus has on its staffing levels. This dynamic further crimps their immigrant members’ ability to complete their census form by phone. To work around this issue, the groups have had to resort, where possible, to directing individuals to the census website, yet another obstacle for immigrant communities to be counted.

Advertisement

The coronavirus is also exposing the widening digital divide in some Latinx communities. “One in five Latinos who reside in Spanish-dominant households in California do not have access to broadband at home,” said Arana, the Latin Community Foundation’s policy director. “This places Latinos at a particular risk of being undercounted. The foundation was working with its nonprofit partners and community health clinics to address this digital divide by establishing questionnaire assistance kiosks where families could use a computing device to fill out the survey. All these kiosks have now been put on hold because of shelter-in-place guidelines.”

Their work became only harder after the Trump administration attempted to include a citizenship question in the Census, and litigation over that effort exposed crucial evidence about the administration’s intentions: a 2015 memo found on a hard drive belonging to the late Republican strategist Thomas Hofeller. Considered by other operatives a master of racial gerrymandering, Hofeller spent his career instructing Republican statehouses on using population data and mapping software to construct congressional districts that advantage white, rural, and registered Republican voters over people of color and urban voters. His handiwork with voting and geographic data helped secure statewide Republican edges in swing states such as Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, all of which were crucial to Trump’s election.

In that memo, Hofeller had recommended that Republicans add the citizenship question to the census questionnaire in order to discourage Latino responses from households that might have a connection with an undocumented immigrant—and thus to dilute the voting power of Latinos and boost the voting power of non-Hispanic whites. Even though the measure was defeated in the courts last year, confusion over the Trump administration’s malign initiative has continued to linger in Latinx communities and, according to experts, has still been discouraging Census participation.

*

As households endure economic disruption for the foreseeable future, an accurate Census count is how our leaders will know where families live and work. Census data are used to distribute $1.5 trillion a year in federal funding to states and local communities, including for schools, roads, hospitals, emergency services, and social programs, former Census Bureau director Thompson noted. More specifically, some three hundred federal programs, such as school nutrition assistance, children’s health insurance, affordable housing, Medicaid, and even adoption assistance programs, have recently depended on Census data to allot public resources to state and local governments, as well as to households.

The stakes are even higher now, as households must still cover months’ worth of rent, food, utilities, healthcare, and life expenses, possibly unemployed, during an indeterminate recession—even allowing for the $2 trillion stimulus package, which affords a one-time $1,200 payment per adult, and $500 per child. And then there are the large and small business owners who depend on good Census results for making informed decisions about where to open factories, offices, stores, supply chains, or restaurants—how to tailor their operations, where to recruit workers, and how to calculate their offer of products and services.

“There isn’t a playbook for this unprecedented crisis facing the 2020 Census,” Mary Jo Hoeksema, the director of governmental affairs at the Population Association of America and a Census expert, wrote to me by email. “Stakeholders are urging Congress to appoint a working group comprised of outside experts to inform any decision about delay or postponement. It is important to note that Congress would have to pass, and the president would have to sign into law, legislation to alter the current deadlines.”

So far, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have not been issuing any nationwide data about race and income in the statistics concerning Covid-19 testing, hospitalization, displacement, and death; nor have most states, counties, and private labs released any such information they may have gathered. But some states, including Illinois, Michigan, and North Carolina, as well as Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, are releasing statistics on coronavirus cases by race—and their data show a disproportionate number of black Americans being affected.

In Illinois, for example, whites comprise 77 percent of the state population but only 39 percent of confirmed cases. According to ProPublica, as of April 3, black Americans comprised almost half of Milwaukee County’s 945 cases, and 81 percent of its twenty-seven deaths, although the county’s population is only 26 percent black. Blacks make up 35 percent of the coronavirus diagnoses in Michigan and 40 percent of Covid-19 deaths in the state, despite the state’s population being only 15 percent black. And the country’s three largest cities—New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago—are releasing data showing the virus’s disproportionately bitter impact on racial minorities, particularly those who are poor. In Chicago, the gap appears particularly dire: 71 percent of coronavirus deaths among black people, who comprise about 29 percent of the city’s population.

People of color, especially in the nation’s most densely populated cities, are running the risk of coronavirus and of going significantly undercounted. Such residents rely on crowded public transportation to travel to essential service and care jobs, to purchase necessities, and to deliver or seek medical care. In high-tech metro hubs like San Francisco-Oakland, Seattle-Redmond, Raleigh-Durham, Boston-Cambridge, and New York City, racial inequality, de facto segregation, and unemployment relegate many residents of color to the sidelines.

Can the Census itself recover after the Covid-19 pandemic? The entwined crises of the coronavirus and the 2020 Census are exposing a ruthless political economy in which only certain types of people count—a world where the immigrant and the non-white may be essential laborers but are rendered non-essential citizens. With this administration’s attitude toward the 2020 Census veering between heedless and hostile, we’re seeing a wholesale effort, in effect, to disappear entire populations considered unnecessary to the Trump GOP’s political fortunes and irrelevant to a digitized, financialized, Dow-centric economy. As one pro-Trump online magazine mused: “Is America ‘better off’ letting people die?”

This story was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.