On a Monday in late March, I sat on an exam table in my obstetrician’s office in Manhattan. The wax paper between my body and the table felt thinner than usual. I was nearly nine months into my second pregnancy—around the time the fetus declared out and out war on my bladder and other sensitive organs. In the twenty minutes I’d been in the office, I had already washed my hands three times and applied Purell even more.

The previous week, when I’d asked my doctor whether it was safe to give birth in New York, her answer had been reassuring: Don’t worry, we’re a big hospital, what happens in the ICU doesn’t affect us in Labor and Delivery. That was before The Times had declared on its front page that New York City was “an epicenter of the pandemic.” Now I asked my doctor the same question and searched her eyes—the only part of her face not covered by a mask—for the same reassurance. I didn’t find it. “If you can leave,” she said, “you should.”

A couple of days later, as a drizzle against my bedroom window turned to rain, I packed a few pairs of stretchy pants, some newborn paraphernalia, a computer, and a roll of precious Lysol wipes into our car, preparing to drive with my toddler and my husband to a friend’s house outside Providence, Rhode Island. My parents, who live in Manhattan, would drive up separately, live with us for the end of pregnancy, and take care of our toddler while I was in labor.

We had all been self-quarantined for two weeks, and none of us had any symptoms, so we figured we probably weren’t vectors of the virus. Still, I worried that the plan would put my parents in danger of contracting it. As we headed up the I-95, I consoled myself by thinking about how aggressively I would disinfect all doorknobs, light switches, cell phones, Amazon packages, each surface methodically doused. I wouldn’t have absolute dominion over my environment, but there was a lot that I would be able to control.

I am a former public defender, and I now write about the criminal system for The Appeal, a publication focused on criminal and social justice. I hear every day from the family members of incarcerated people who are asking themselves the same thing I am now: How can I keep my family safe? But they have real reason to fear, far more than I do. On Rikers Island, according to a report by the Legal Aid Society, the Covid-19 infection rate is many times higher than the rate in Wuhan, China, or in Lombardy, Italy, or in (the rest of) New York City. The Cook County Jail in Chicago was recently reported to be the largest-known source of infections in the US.

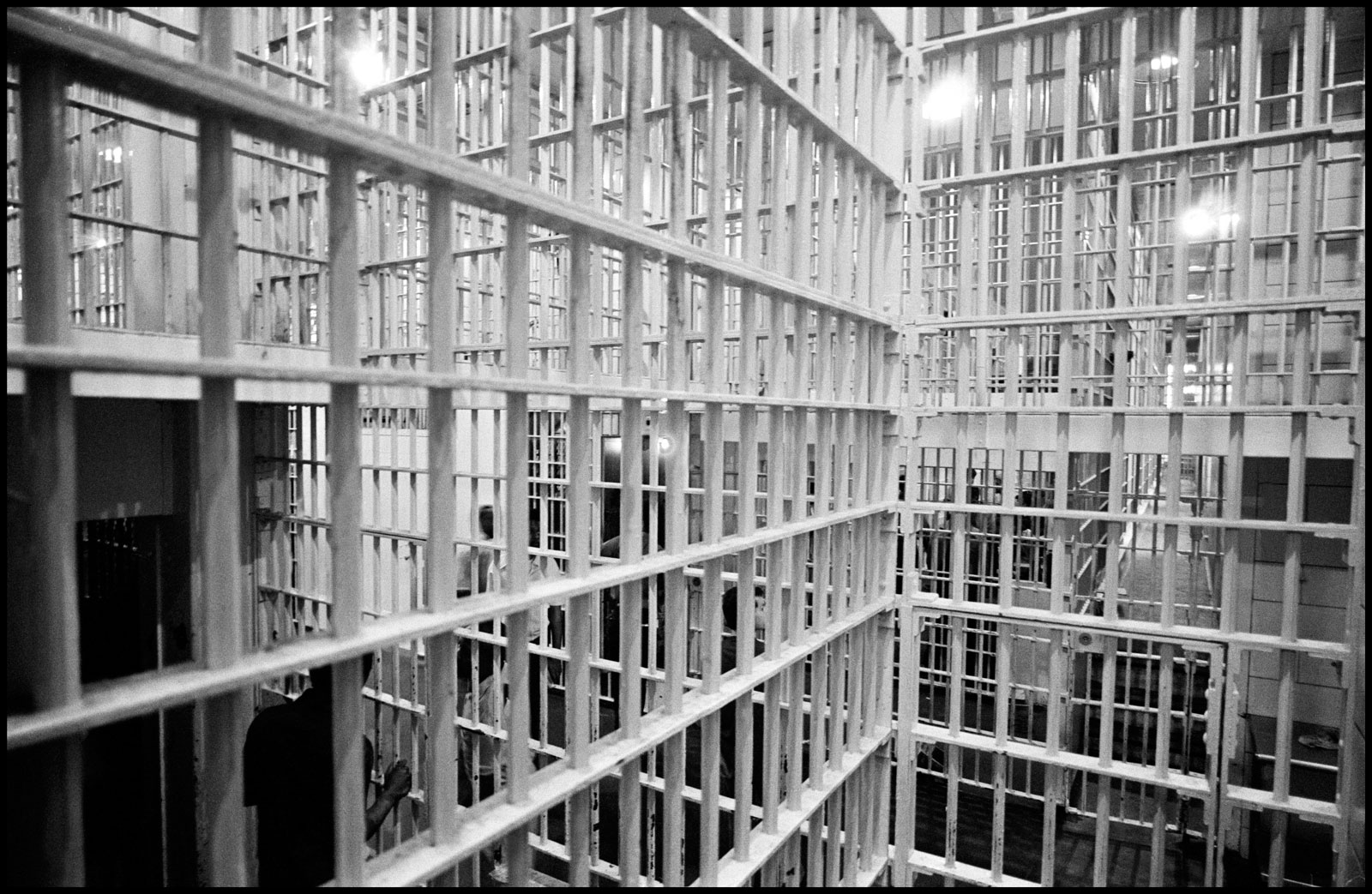

If my child were locked up at Rikers, rather than strapped into a car seat in the back of my car, then I wouldn’t be able to wipe down his groceries, or sing “Happy Birthday” twice while he washed his hands. If I were pregnant in jail, I wouldn’t be able to get in my car and seek a safer environment in which to give birth. People inside prisons and jails often sleep a few feet apart, live in unsanitary, at times vermin-infested conditions, and typically have no ability to disinfect public phones, meal trays, tables, toilets, or anything else they touch.

Prisoners are generally prohibited from having hand-sanitizer at all; because it’s made of alcohol, it’s considered contraband. By prison administrator logic, preventing incarcerated people from drinking hand-sanitizer is more important than preventing them from dying in a pandemic.

One of my young clients from my years as a public defender was repeatedly attacked in jail because he’d grown up on a certain block in the Bronx, and his assailants had grown up on a rival block. Once, they had him jumped from behind. Another time, his throat was slashed. Miraculously, he survived. These years later, he still has scars.

When he was in Rikers, his mother called me every day, and I passed her messages on to the jail, trying to get him some protection. If he were out, she said, she could at least try to keep him safe at home; with him there, she could only pray. “I’m not even religious,” she told me, “but what else do I have?”

Another client, a transgender woman, was being taunted and abused by guards, sometimes sexually, and was having suicidal thoughts. Her mother would call me in the middle of the night, distraught, begging me to do something. I did the only thing I could. I asked for her to be moved to protective custody—solitary confinement, essentially—and put on suicide watch. She was isolated and miserable there, and the abuse did not stop, but she did stay alive.

Advertisement

I’ve thought often of a third client of mine, whose girlfriend was in her ninth month of pregnancy. Prevented from being present at the birth of his first child, he had a breakdown. He called me saying that, in desperation, he had swallowed a handful of pills he’d found. I spent seven hours trying to convince someone, anyone, at the jail to care enough to check on him. Again and again, I was told, “Counsel, calm down. There’s nothing we can do.” Eventually, he was taken to the hospital. He recovered, and then, a few months later, he won at trial and went home to his baby.

Like the great majority of prisoners in jails across the country, my clients were held in on bail, not convicted of anything. But the punishment they were enduring was just as real as a sentence. The judges who were responsible for incarcerating them because they couldn’t afford bail would never have admitted that they were sentencing my clients to slashings, sexual abuse, or mental breakdowns, but they didn’t order their release when I told the court that this was happening. These outcomes were not mandated; they were not intentional; but they were considered permissible. They came with the territory.

During the coronavirus pandemic, most jails and prisons have abjectly failed to protect the health of the people they are housing. A fifty-six-year-old man I met through my reporting, who is serving a life sentence at Angola prison in Louisiana, recently told me that he lives in a dorm with ninety-six other men, their beds two feet apart. He has to pay for his own soap. Some of the men in his dorm can’t afford soap, so they go without. None of them have masks or disinfectants.

Elsewhere, though, some authorities have begun to do the necessary thing: decarcerate. In that sense, the impossible seems, suddenly, to have become possible. Florida prisons announced they would temporarily stop accepting new prisoners. Judges in Texas have voted to release people charged with low-level felonies. Prosecutors in Philadelphia have called for a moratorium on low-level prosecutions, and police in Los Angeles have scaled back arrests. Even Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which has long resisted calls to reform its gratuitously cruel practices, recently decided to stop arresting people, except those who are deemed safety risks.

I welcome these measures but find myself conflicted all the same. Authorities should be decarcerating—such a move is long overdue—but it’s frustrating that it is happening only now, when the country is afflicted by a new scourge. It isn’t as if Covid-19 is the first threat to the welfare of incarcerated people. Criminal justice advocates have long warned that abuse and neglect in corrections facilities is itself a death penalty. Guards in this country have killed prisoners through acts of violence like locking them in boiling showers until they burn to death; they have gouged out prisoners’ eyeballs for refusing to leave their cells. These might be exceptional horrors, but far more common are prisoner deaths that come from officers’ mocking or shrugging off their medical complaints.

Covid-19 isn’t even the first infectious disease to ravage prisons: The rate of HIV among prisoners is five to seven times higher than that of the general population; the rate of hepatitis C among prisoners is fourteen times higher. Perhaps it’s the scale of Covid-19, or the suddenness of its arrival, or the risk it poses to corrections staff, that distinguishes it from other diseases that have endangered so many of my clients without engendering the same kind of response.

*

Right before my husband, son, and I got on the road, while my toddler was stalling by pretending to change all of his stuffed animals’ diapers, I got a push alert: the president was considering imposing a mandatory quarantine on the entire tristate area. However rational and doctor-approved our plan to leave New York, it all felt ominous, as if I were in an early part of a dystopian film—the part where the characters think things can’t get much worse, before things start to get much worse. The rain was pounding by then, which didn’t help. My son, still applying imaginary diaper cream to a toy octopus, didn’t ask what was wrong, but he didn’t object when I picked him up and rushed him into the car.

The governor of Rhode Island had just announced that any car with New York license plates would be stopped by the National Guard. And even though all they could do was take our contact information and remind us to stay home for two weeks upon arrival, getting pulled over by officers in fatigues that said “Military Police” only heightened the ominous mood. As a lawyer, though, I know that there are checks on the government’s ability to control our actions and movements—checks that do not constrain authorities’ power in prisons and jails.

Advertisement

Today, I’m a few days away from birth, nesting with my family, far from our home in the epicenter of the virus. We stay inside, we continually scrub every surface we encounter, and we wait. Someday, the virus will recede. I can only hope that, when it does, so too will the kneejerk “no” that corrections staff dole out when they don’t want to think about how to protect the people in their facilities. In my more hopeful moments, I imagine that soon, a worried mom calls a jail hoping to keep her son safe, and what she hears is something else. Instead, I hope the guard on the other end of the line pauses, thinks for a moment, and says, “I hear you. Let me see what I can do for your son.”