“Two images recur throughout [my] work,” wrote Moira Dryer in 1991, “those of loss and desire.” How, I keep wondering, can those two things be images? I’d like to ask her, but I can’t; Dryer died of cancer the following year, at the age of thirty-four. She already knew more about loss than many people her age. In 1982, fresh out of New York’s School of Visual Arts, the young Torontonian married a fellow student; fewer than eighteen months later, her husband was dead, of a congenital heart ailment. Later, most of her career, though prolific and highly successful, would be shadowed by her own illness.

Dryer’s talent as a painter was to draw poignancy out of an almost generic pictorial vocabulary—stripes, blotches, drizzles of drippy color—and to put her formal reticence at the service of an intense playfulness, in paintings that emphasize their own three-dimensionality, playing on the edge of sculpture. Characteristic, as its name might imply, is The Signature Painting (1987)—like many of her paintings, a two-part invention: A small panel seems to offer a comment, a sort of “Yes, but…” on its larger companion, which prominently displays the artist’s initials, MD, with beneath it a jaunty flourish that seems to have transmuted, in the smaller panel, into an infinity sign. Dryer seems to be joking with the idea of the signature as a sign of artistic authenticity and of a “signature style” as a prop for an artwork’s economic value while suggesting that the common and easily duplicated elements out of which she has built her work can still be put to better (and more genuinely personal) use than merely certifying a sense of self.

Dryer’s work has resurfaced periodically since her death—most notably in 2000, when a small retrospective organized by the Art Gallery of York University in Toronto opened in St. Louis and toured to Toronto, Waltham, Massachusetts, and Baltimore. But mostly, her art has lived in the memories of those who fell in love with it during the brief period when she was exhibiting regularly, beginning with her 1986 solo debut at New York’s John Good Gallery up through a posthumous MoMA Projects room in 1993. I’m one of those longtime admirers, as is New Yorker critic Peter Schjeldahl, who in 1998 wrote that her death six years earlier still hurt. So, also, is the painter Ross Bleckner, who called her “the Katharine Hepburn of abstract painting. She was beautiful and wind-swept and fierce and intelligent and she made things look very easy. There was a youthful mastery.” Yet another keeper of the flame is the curator Valerie Smith—the first person to write about Dryer, in Flash Art in 1980—who recalls her as “singular in her commitment to art.” In her early work, Smith writes, Dryer “continued to express atmospheric transformations of the land and sea irreverently and emotionally, as if they were her own” and later “took control of her acute sense of mortality by challenging herself to possess fate.”

Perhaps more important than the way Dryer’s paintings have continued to live in the memories of those who saw them in the Eighties and early Nineties is the way her name has lived on as a kind of password among certain younger abstract painters who may never, or only rarely, have had a chance to see her work in person. In an article published in the Brooklyn Rail in 2012, the English painter and critic David Rhodes recalled his impression, reading in London about Dryer’s work years before, “that New York had done it again; a tradition was being recoined and revitalized,” thanks to her “taking a long look at abstraction and quickly coming up with something fresh and new.” Her reputation continued to circulate, sub rosa, among painters hoping to work with abstraction without bombast or the illusion of progress, to paint in ways that might be at once more intelligent and more full of feeling, more playful and yet more earnest.

Two recent shows of Dryer’s work in the Washington, D.C., area—both cut short by closures required by the coronavirus pandemic—amounted to the best chance in twenty years to reconsider her work. The one that was more widely seen took place at the venerable Phillips Collection. Curated by Lily Siegel, it was titled “Back in Business” and encompassed twenty-two paintings—some of them quite sculptural and one of them freestanding rather than wall-mounted—made between 1985 and 1990. The second show, also curated by Siegel, was at the Greater Reston Arts Center. Getting there, if you’re not a car-owning local, means taking one of Washington’s Metro lines all the way to its very last stop in a part of Virginia that seems choked by corporate development and then getting a taxi.

Advertisement

It was worth the effort. The show was described in the venue’s press release as providing, in contrast to the Phillips show, “an intimate look at the artist’s practice through works given as gifts to friends and family, many never previously shown publicly”—which might suggest a scrappy gathering of minor pieces, things of possibly more sentimental than aesthetic value. Nothing could be further from the truth. While the Reston show included several very early pieces, from before Dryer came into her own as an artist, most of the dozen works on view, from around 1980 through 1991, were just as impressive as those displayed at the Phillips. The show in Reston, by the way, was called “Yours for the Asking.” Like the title of the show in Washington, it was taken from a newspaper headline clipped out and saved in Dryer’s notebooks—saved, presumably, as a potential title for a painting she never got to make.

To understand what was so striking, to some of us, about Dryer’s work in its time—what is still unusual about it today—it helps to know what she had learned from the art being made around her, and what she had learned to avoid. Her work was as far a cry from the theoretically overdetermined Neo-Geo—think of the cool synthesis of Pop and Minimalism, in Peter Halley’s fluorescent “cells” or Jeff Koons’s basketballs mysteriously floating in fish tanks—as it was from the emo-posturing of the Neo-Expressionism that had been fashionable a little earlier. Robert Ryman seems to have been a model, specifically his method of turning what were usually “secondary” aspects—the surface onto which the paint is brushed, the hardware that affixes the painting to the wall, even the artist’s signature—into primary elements of painting. She must have had her eye, too, on Carroll Dunham, who through most of the Eighties (his art took a very different turn toward the end of that decade) made abstract paintings on wood or wood veneers, often using casein paint, among other materials, to create a sort of free-associative abstract graffiti that seemed to take the irregular grain patterns of the wood surfaces as inspiration for improvisations that could end up as bluntly corporeal metaphors.

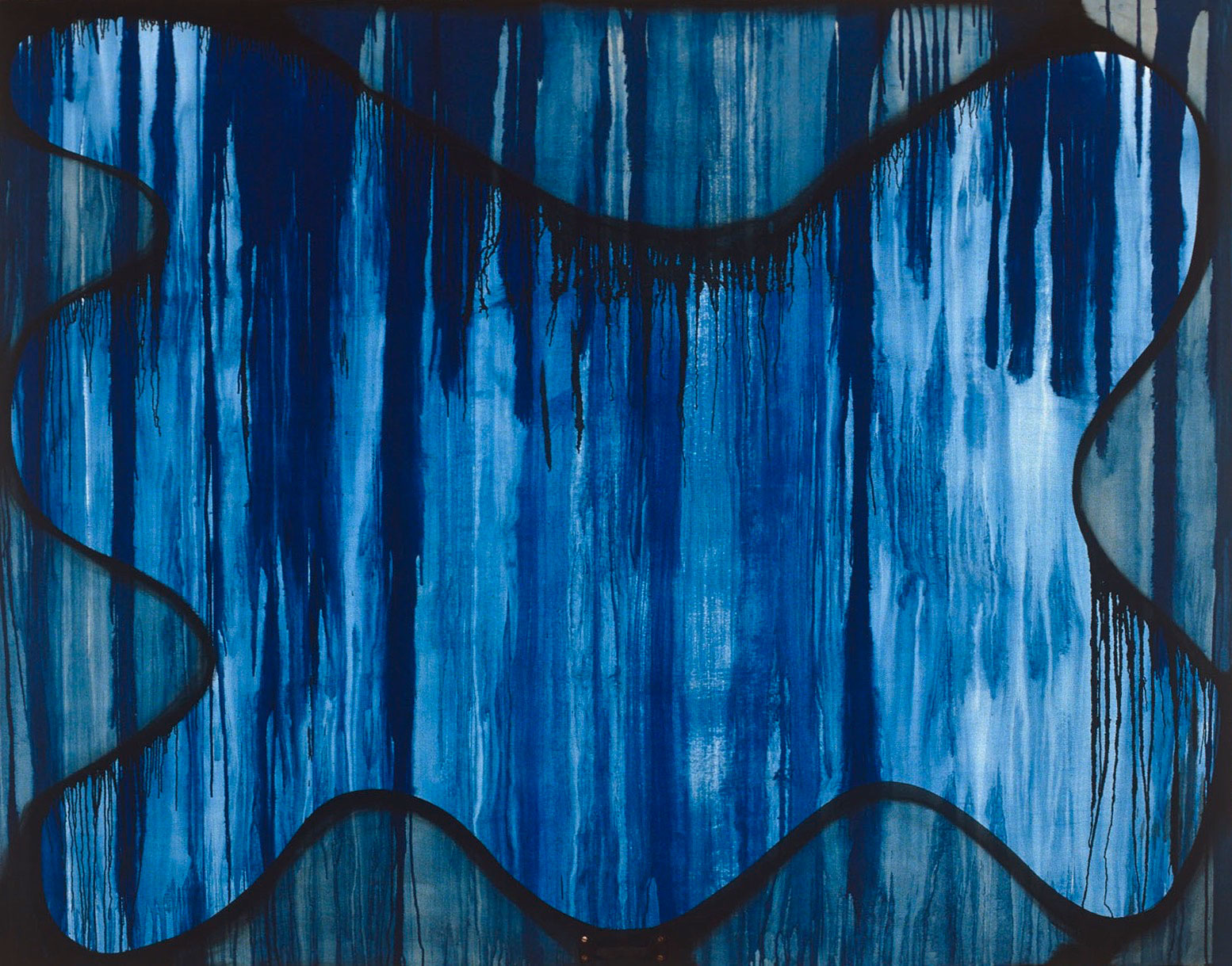

Casein on wood were Dryer’s preferred materials. Casein is a water-soluble paint derived from milk protein that has a matte, cloudy look to it. An ancient material, in recent times it has been used more by illustrators and scene painters than fine artists; perhaps the medium caught Dryer’s attention when she was supporting herself as a freelancer making theater sets during the lean years following her graduation from art school. (In the Phillips Collection catalog, Siegel repeats the story, mentioned often in other sources, that Dryer worked as a set designer for the celebrated theater company Mabou Mines. This seems to be an urban legend; she’s not credited as a set designer on any of their work. She probably worked much lower down on the theatrical totem pole.) Dryer often used her casein in thin washes, and she never prepared her surfaces with a primer such as gesso, so the grain of the wood remains visible, becoming part of the image, with the applied color acting as a sort of veil.

In other words, the works always call attention to the fact that they never start with a neutral surface like a canvas but from something that was already pictorially active before the artist even touched it—and that sense of touch, of physical contact, is always part of the point: as rarefied and intellectual as Dryer’s work can be, it is always anchored in its physicality. And I can’t help wondering how much paint she had to use; surely a lot of it must have sunk into the wood itself rather than remaining visible on top. This could almost be an allegory for Dryer’s whole art: more had to go into it than you can see on the surface, but you can sense the presence of something held in reserve.

But if Dryer’s work, as she herself put it, “emphasizes an emotive identity,” it wasn’t in the blatantly demonstrative manner of much of the fashionable painting of that moment—Julian Schnabel, Anselm Kiefer, Francesco Clemente, and so on. It wasn’t even as outgoing as the rambunctious almost-abstraction of Elizabeth Murray, who was one of her teachers at SVA and subsequently hired her as a studio assistant. Murray was a legendary mentor to many young female artists, and commentary on Dryer’s work often mentions the elder artist’s influence. But Valerie Smith, in her essay for the catalog of the Phillips Collection show, shrewdly points out that there were two dominant poles of influence at the school in those days. Murray was one; the other was Joseph Kosuth, who was not only one of the pioneers of conceptual art but also its strictest and most demanding inquisitor. In 1969, he had definitively excommunicated painting from the realm of serious art with the declaration that “Being an artist now means to question the nature of art. If one is questioning the nature of painting, one cannot be questioning the nature of art.” Art was a purely cognitive, not an expressive practice, and painting, in Kosuth’s eyes, was merely “the vanguard of decoration.”

Advertisement

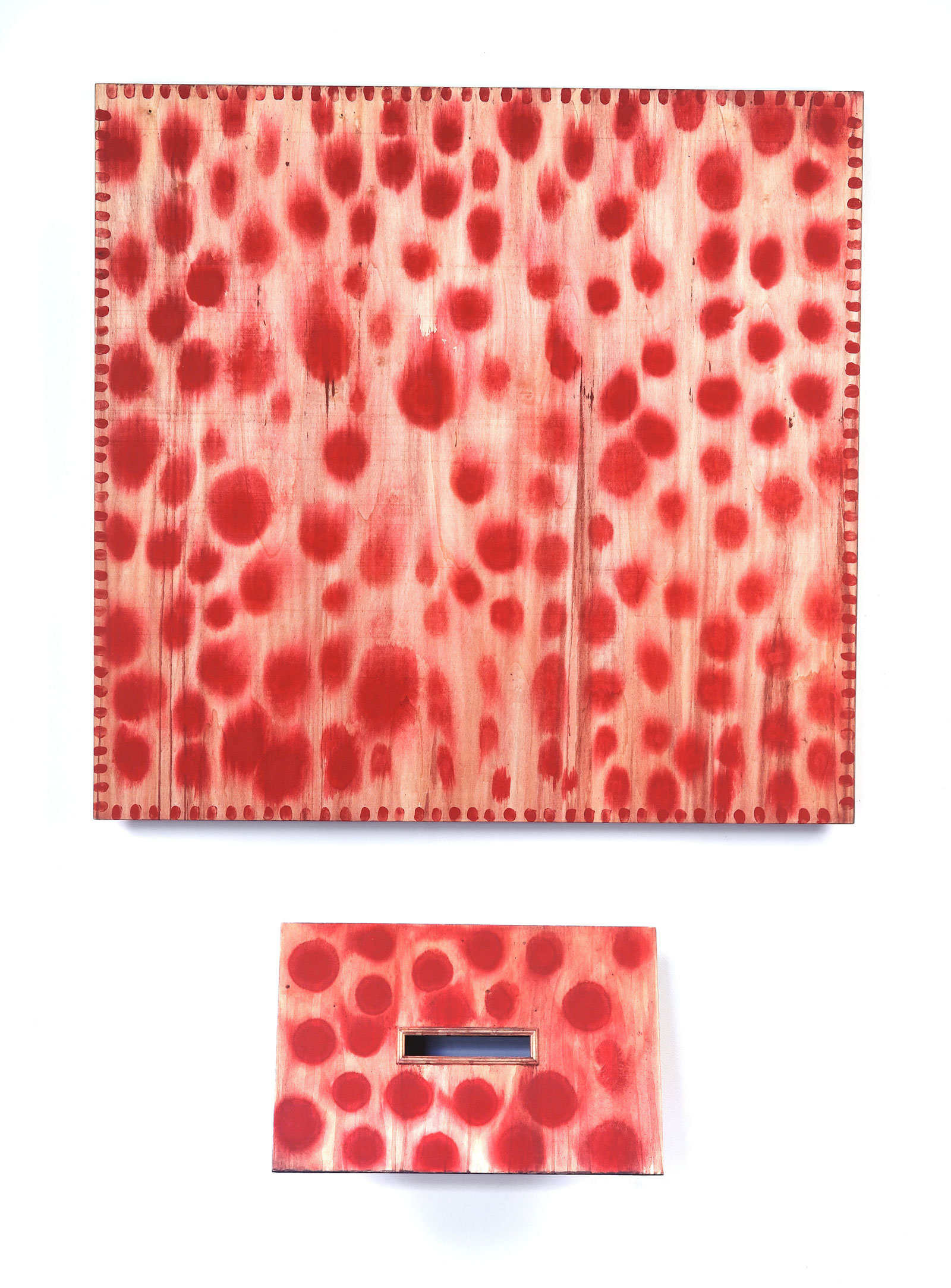

Dryer, you might say, found in Kosuth’s dismissal of her chosen medium both a jeu d’esprit and a job description. She liked to employ ornamental figures structurally, fancifully re-marking the edges of her paintings, with, for example, the almost folk art-like dabs of red around the perimeter of the larger section of The Power of Suggestion (1991), or the scalloped borders she often gave her works. She would sometimes turn a decorative motif into the painting’s main subject, like the wreath that substitutes for the head promised by the title of Portrait #124 (1989). Or she might take utilitarian hardware and use it ornamentally, like the garage door handle affixed almost unnoticeably to the bottom of Suburbia (1989). The significant and the seductive alternate playfully in Dryer’s work. One of her preferred motifs was that abstractionist warhorse, a pattern of stripes—structural or decorative, take your pick. A favorite trick was to twist those stripes into whorls like those of a fingerprint: a mark of identity, but in this case, no one’s in particular.

Kosuth, or the atmosphere he fostered, had sown a seed of doubt about the very activity of painting—a suspicion Dryer could neither confirm nor escape. And so—in contrast to someone like Murray—she practiced a chastened, self-questioning form of painting. Was it too much or next to nothing? Her doubt did not undermine the work but became part of its material, even of its energy, a source of those feelings of loss and desire, or even just those less exalted experiences of “irritation, tension, a little anxiety and conflict” that she once told Schjeldahl paintings needed to allow for. She took to heart the idea that whatever art might be—painting or not—it had to be something more than a venting of emotion. Holding it in was the stronger gesture.

As Dryer wrote in an undated studio note included in a vitrine:

Paintings have a conceptual resemblance

– visible manifestation of the visible

– addressing the psyche

– painting: a realm to know and understand what might otherwise be mysterious

– avoiding heroic & erotic stimulants

– acknowledging a kind of world.—ruin or promise

More than conceptual, in fact, Dryer’s work was discreetly philosophical. Hovering somewhere in its background is Jacques Derrida’s 1978 book La Vérité en peinture, which was translated into English in 1987 as The Truth in Painting. In it, he explored the idea of the parergon, a Greek word meaning “supplement” or “embellishment”—something secondary to a work, ergon. Immanuel Kant had cited as an example the frame of a painting. But wait, said Derrida: in mediating between the work and its surrounding, the frame undertakes its own work, and shows that what’s supposed to be the work itself is something less fixed, less autonomous than it claims to be.

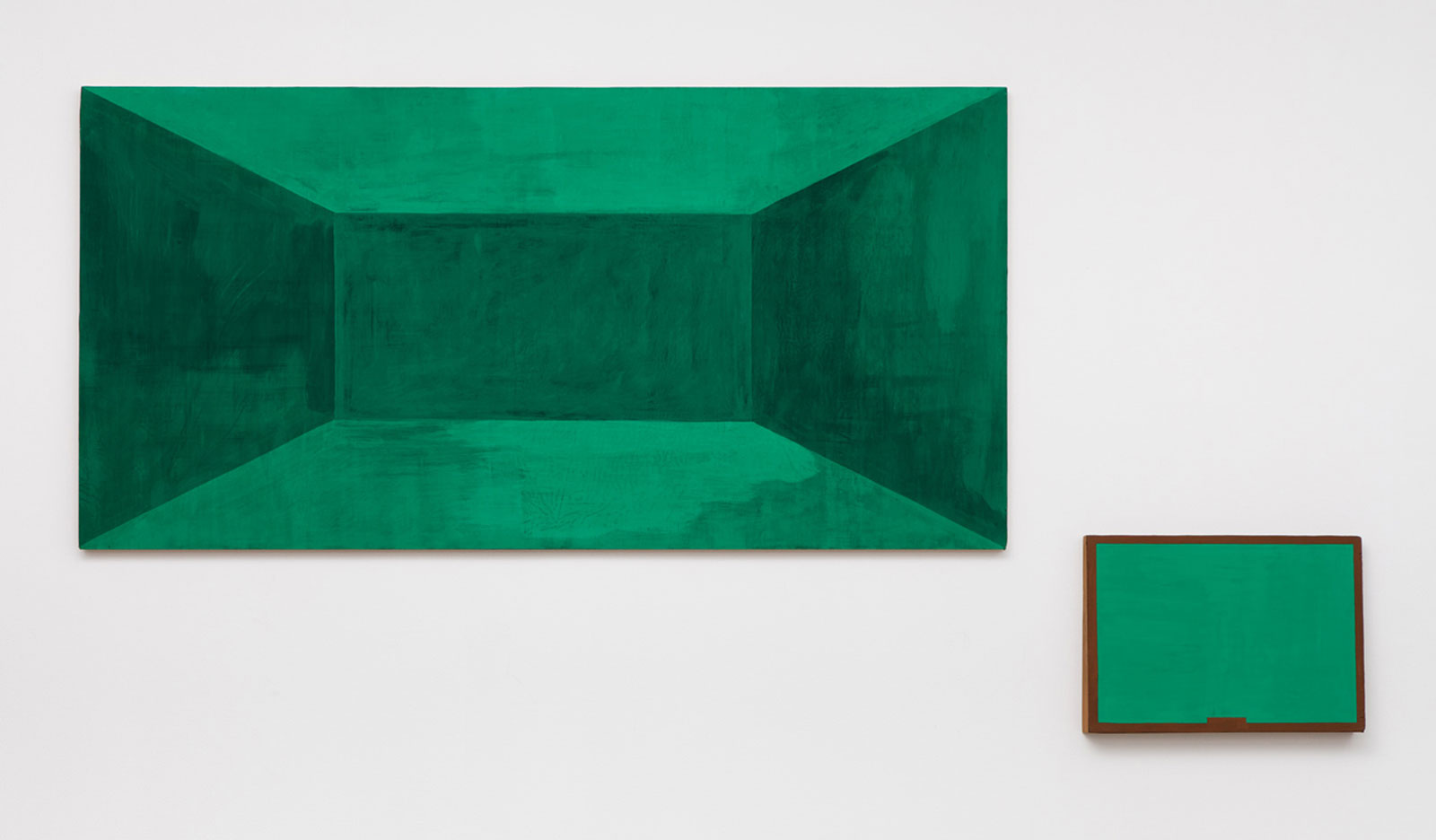

Well before Derrida’s book was translated, Dryer had come to a similar realization, and made it a theme of her work. Many of her paintings are diptychs in which a much smaller panel appears to be a complement to or commentary on a larger one—examples at the Phillips include an untitled green painting from 1985; The Signature Painting; and D.D. (Dangerous Days) (1990), in which a blank steel plate seems like a placeholder for a text panel yet to be written.

For Dryer, the parergon was never an abstract philosophical issue. It had to do with the rather anxious doubt as to whether and how a painting could justify its presence: Could highlighting it by adding another element, a sort of diacritical emphasis, ever do the trick? I suspect there were also deeper questions involved, in which the painting-object tended to work as a stand-in for a human actor: Could one alone ever be in itself a whole? And if not, would a pairing achieve completion, or merely redouble the insufficiency of the one? Dryer never got to arrive at a final answer. Even a much longer lifetime probably wouldn’t have sufficed for that. Her art lives because the quandaries that produced and bedeviled it still touch us.

“Moira Dryer: Back in Business,” temporarily closed, was on view at the Phillips Collection and will be there through December 13. “Moira Dryer: Yours for the Asking” was at the Greater Reston Arts Center.