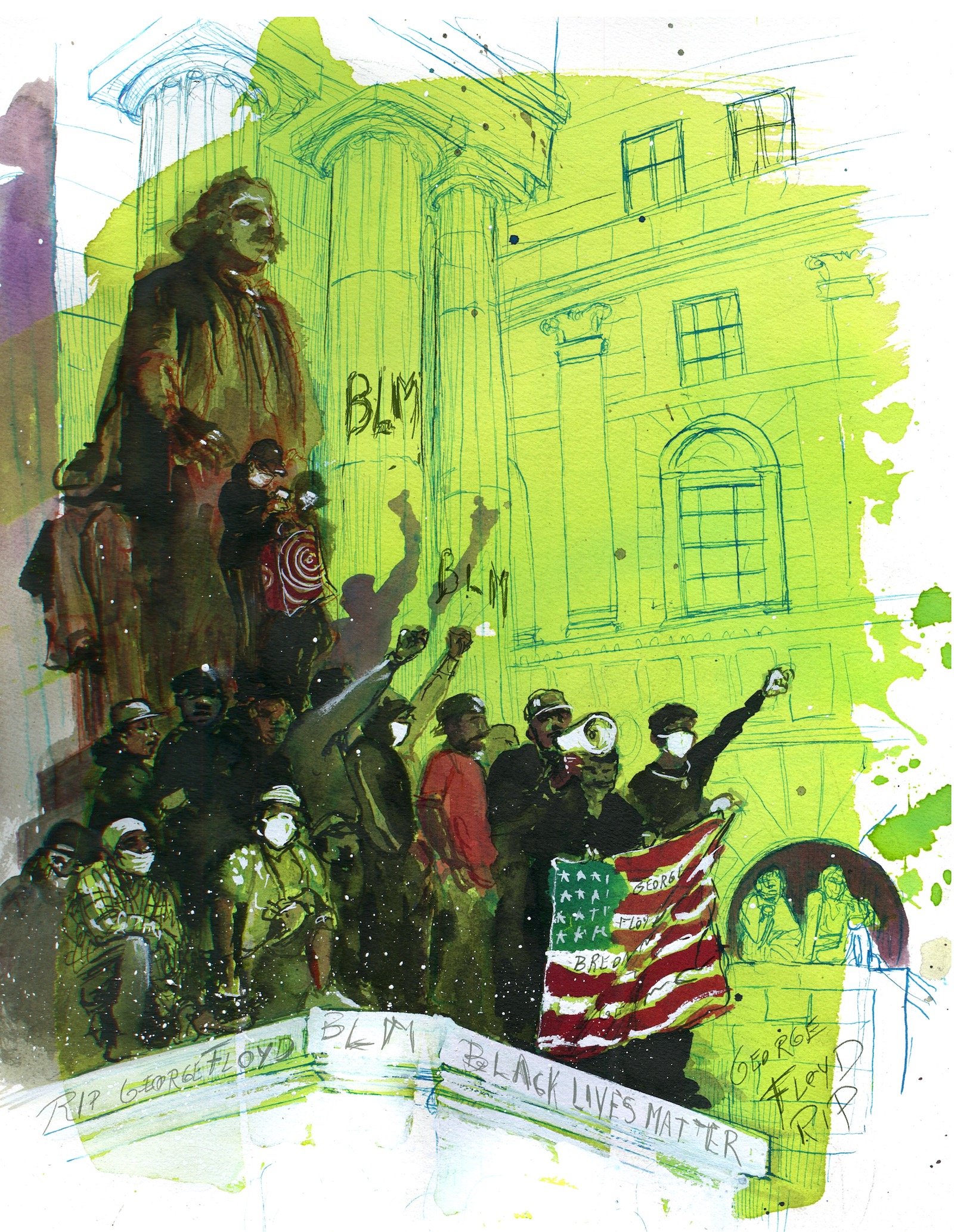

Last week, in New York’s financial district, a black youth stood at the base of a statue of George Washington, a plantation owner who wore as dentures teeth taken from those he had enslaved, and told thousands of young people that they were the embodiment of God. Some fifteen minutes later, they spilled through the winding streets of Lower Manhattan, and chanted, in unison, “NYPD, suck my dick.”

This was one of the roiling mass of anti-police protests that have consumed New York for over a week, protests so numerous and mobile that they were difficult to track, but that snaked several times a day through every borough, their chants loud enough to reach the windows of self-isolating apartment-dwellers and draw them out onto the streets. George Floyd’s murder was the tipping-point, but there had been so many other, more proximate outrages and provocations.

For the past month, New York City police had been assaulting black people on the pretext of enforcing social distancing. One officer, Francisco Garcia, screamed a racial slur at a NYCHA groundskeeper, then slugged him in the face, and knelt on his head in the manner of Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis police officer now charged with the murder of George Floyd. NYPD officers had slammed a young mother face down in a subway station, in front of her screaming toddler. They dragged off a little boy for the crime of selling candy. In Spanish Harlem, they forced black boys to kneel in the dirt.

Every few days, a new video of misconduct surfaced on social media. Yet the officers involved suffered no real consequences. Nor did they show any shame, let alone contrition.

All the while, the coronavirus was tearing through the black and Latino communities in which about 60 percent of the city’s essential workers live, leaving poverty and death in its wake. The mayor and governor postured, but did little to staunch the wounds. The rich fled to their summer homes, while New York’s working class survived through mutual aid. When the state government pleaded that its coffers were empty, and the Trump administration told the city to drop dead, black and Latina organizers packed groceries for seniors, obtained personal protective equipment for nurses, delivered food in the projects, and kept their neighborhoods alive.

Meanwhile, a city government that claims to be on the brink of bankruptcy is still shoveling money at the NYPD—as, each night, its officers have been out cracking skulls and pepper-spraying faces, with a glee only enhanced by all the overtime they earn with every hour. After fewer than six years on the job, a New York cop can be earning six figures (including overtime payments), and in many counties in the New York metro area, officers retire with annual pensions of an equivalent amount. Since a police pension is determined by a combination of salary and overtime, New Yorkers will be paying for these beatdowns for decades to come. New York cops might sound blue-collar by their accents, but taxpayer dollars put them solidly in the upper-middle class—and as much as they are enforcing white supremacy on the streets of Brooklyn and the Bronx, they are also members of an elite committed to defending its own prerogatives.

As for the protesters—and bystanders, lawyers, and journalists—whom these officers swept up? In the Bronx, while boxed in and waiting to be cuffed, former congressional candidate Andom Ghebreghiorgis witnessed a woman going into labor. Another convulsed in seizures. Blood dripped from the baton wounds police left in protesters’ skulls. Ghebregiorghis himself spent at least six hours with his hands agonizingly zip-tied behind his back. On another night, Jason Rosenberg, a programmer for the 92Y, emerged from jail covered in blood, with a broken arm and a head wound that required six staples to close. A source familiar with the situation in the holding cells told me of a woman who had miscarried after being arrested. Another pregnant woman was beaten, left handcuffed, and denied water.

One night, as I walked over to drop off food with the jail support team at One Police Plaza in downtown Manhattan, I saw three male officers leading a young woman down a dark alley away from the building; a source later told me that police snuck injured protesters out the back and away to far-flung detention centers to keep them out of view of legal observers and press. Though numbers are fuzzy, the NYPD has reportedly arrested more than 2,500 protesters in recent days. According to the Legal Aid Society, police held some three hundred protesters longer than the legal twenty-four hours. The NYPD prevented many from contacting their lawyers.

There will be hundreds, likely thousands, of claims for damages because of the police’s violence. Last year, the city paid out nearly $70 million to settle police misconduct cases, up $30 million on the previous year; that number will swell beyond comprehension in 2020. Yet none of this comes out of the police budget: we, the broke and beaten residents and taxpayers, will be paying for their abuse of us.

Advertisement

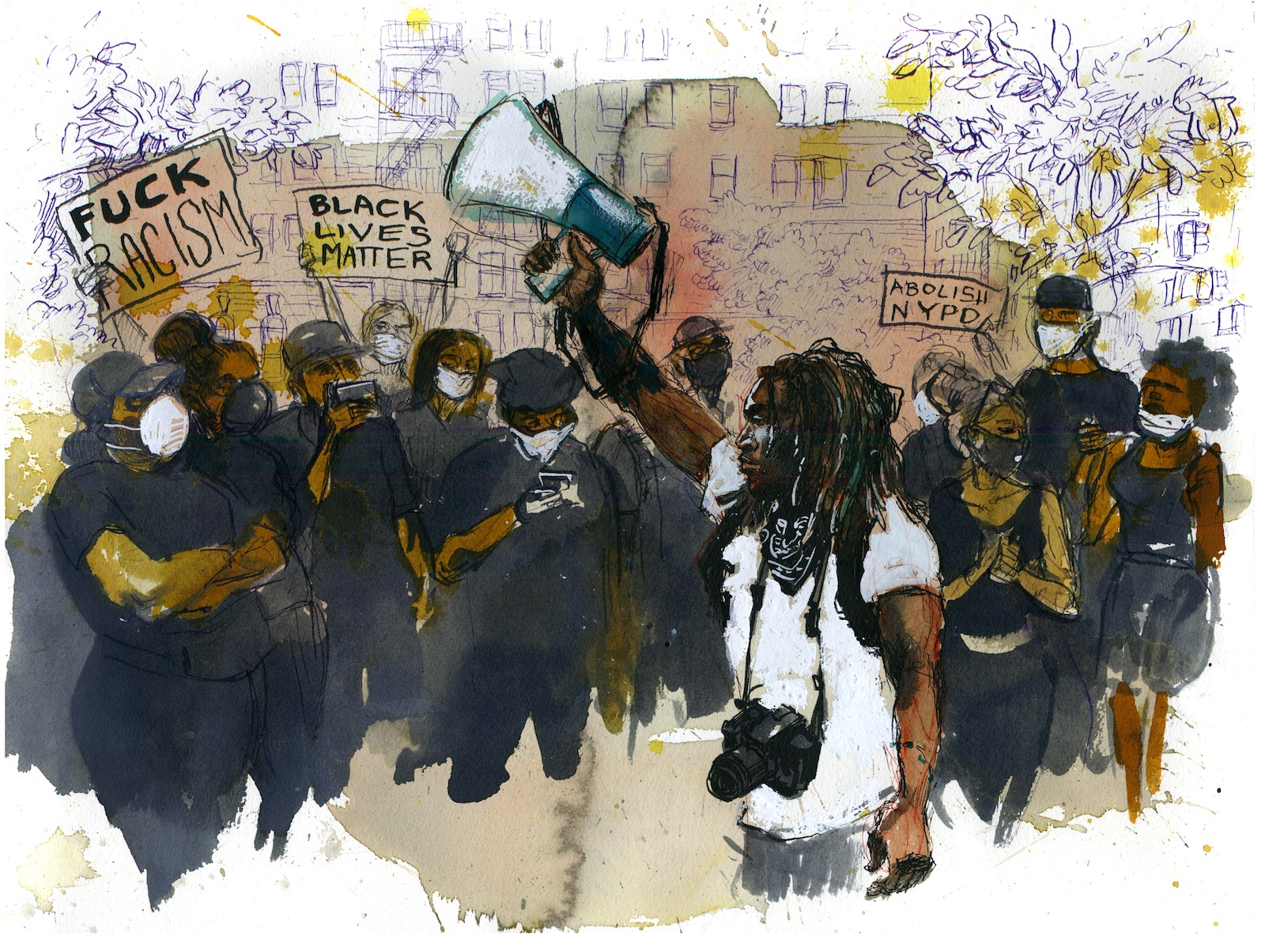

In this light, the call to “Defund Police” hardly extreme—though it’s a principle that even progressive politicians like Brad Lander have shied away from committing to on camera. For decades, black radical thinkers like Angela Davis and Mariame Kaba have called for police and prisons to be abolished; the protesters have taken up their demand. At a march in the Bronx, a young woman said not to get it mixed up: there were no good cops, and the movement wanted rid of them. They come from slavecatchers and the KKK, she said.

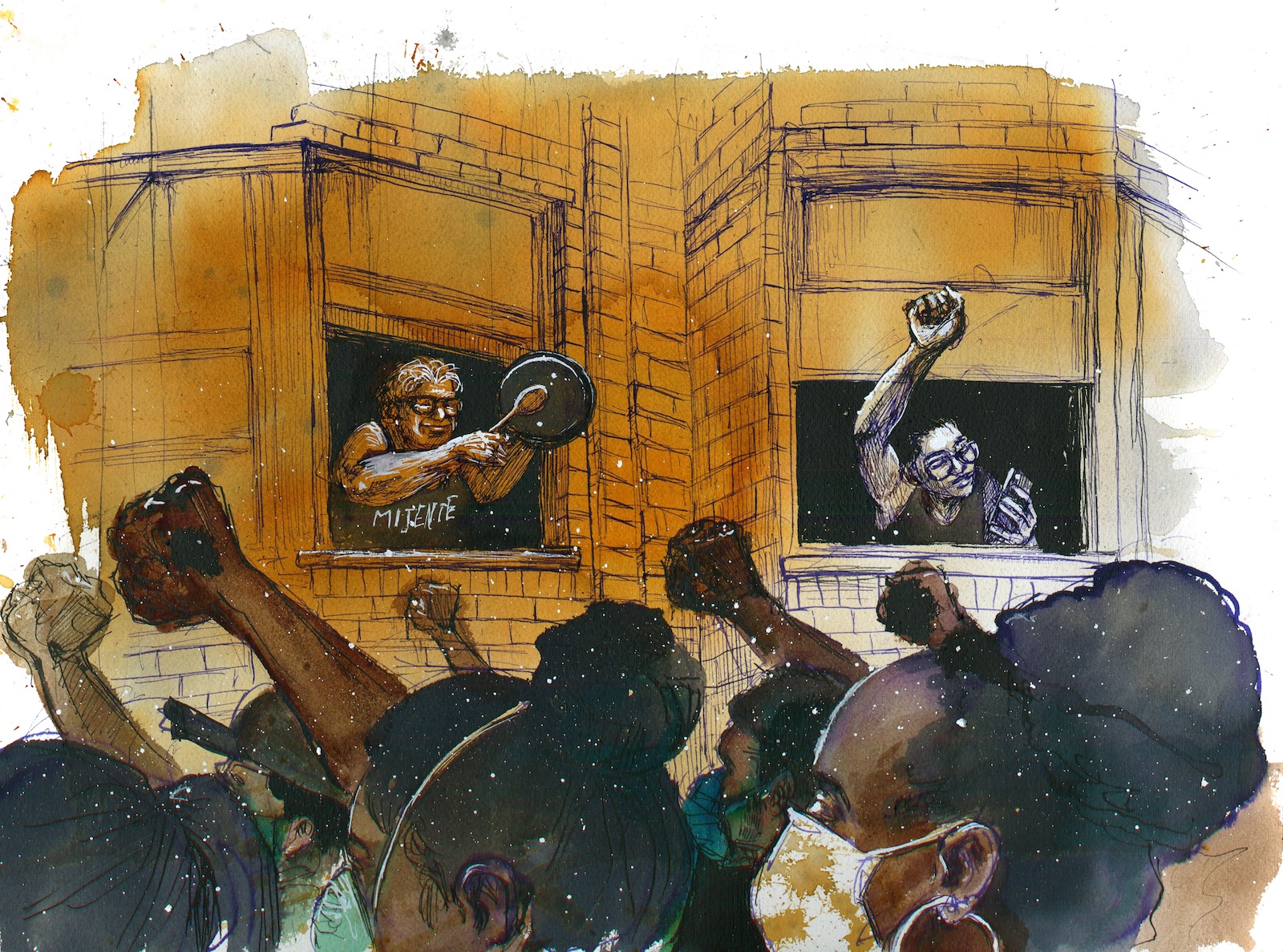

Her fellow protesters were mostly young, and had grown up fearing the police who patrolled the corners of their neighborhoods. Some had been kettled and beaten and doused in pepper spray the night before, alongside Andom Ghebreghiorgis. Now, as they marched down Grand Concourse, cars honked in support. Bystanders raised their fists. An abuela leaned out her window and beat a pan with a wooden spoon in approval—a gesture made famous in Puerto Rico’s anti-government protests the previous summer.

As evening fell, and curfew passed, I walked through my neighborhood, the very Wall Street that had deformed so much of those kids’ lives. Graffiti shouted from the walls. Some fast-fashion chain stores had been looted. Ever since protesters torched that police station in Minneapolis, politicians feared the people almost as much as they feared a backlash from the police. The Minneapolis City Council pledged to disband its police department. Around the country, district attorneys brought charges against officers caught beating protesters on tape. Inadequate though they were, these actions represent some of the most significant concrete victories in reining in police brutality in the two decades since New York cops murdered Amadou Diallo. All the polite, incremental reformism—of sensitivity trainings, tweaks to use-of-force rules, and appeals to better nature—was revealed as hollow in the face of the protesters’ justified fury, of their courage, of their pride.

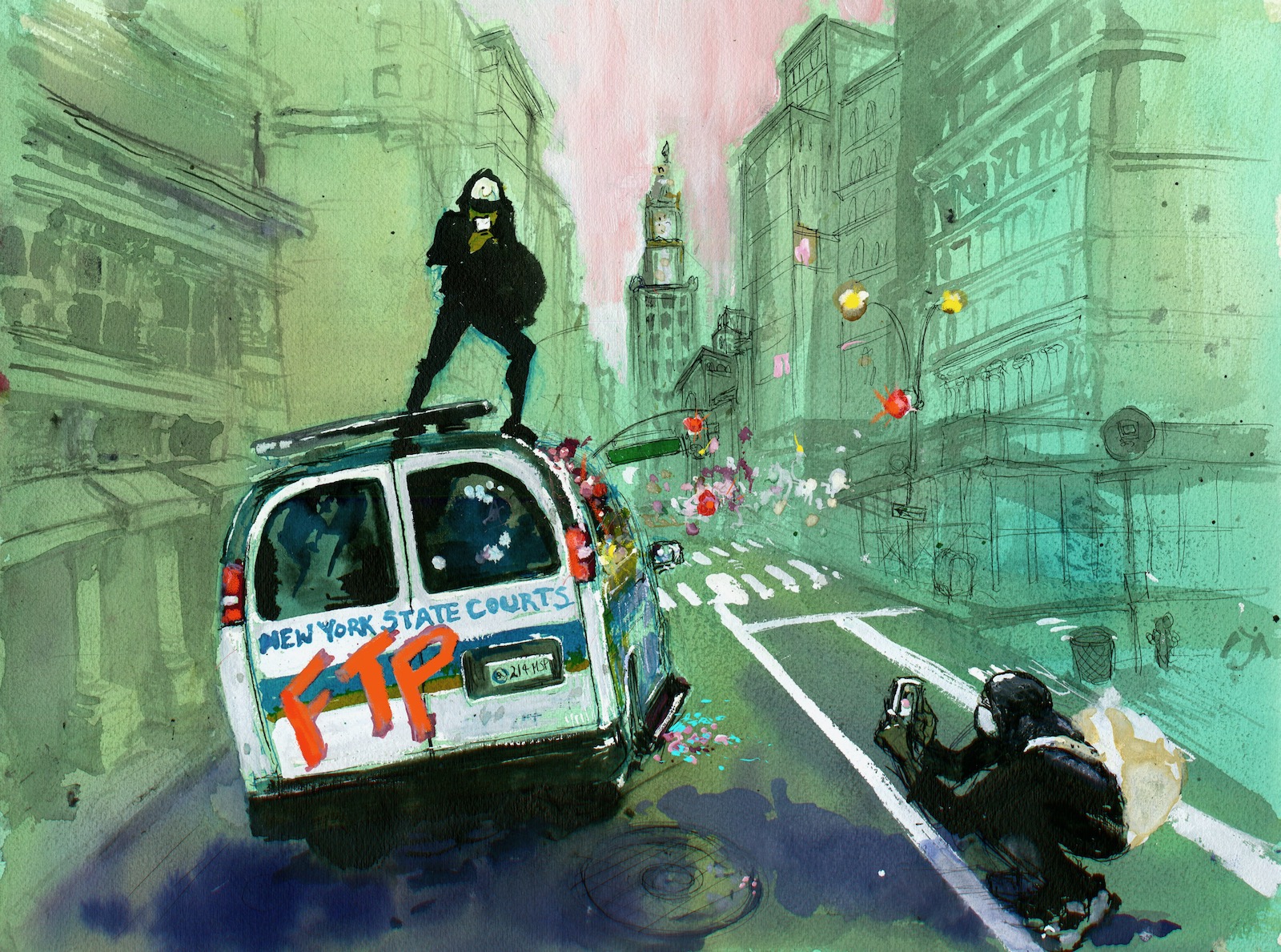

On another night, I saw a police courts van sitting on now-boarded-up Broadway, its windows smashed. Someone had scrawled FTP, short for “fuck the police,” on every side. When I walked by, a kid in black stood atop it while his friend shot photos. I asked to take his picture. He agreed. “You’re gonna get a million likes on Instagram,” he told me. He stood there as if astride the world.