My parents were married at six o’clock on Sunday evening, October 25, 1936, at the Quincy Manor in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, and a week or so later, they began clipping coupons from the front page of The New York Post, one coupon a day, and mailing them to the Post, twenty-four coupons at a time, which coupons, along with ninety-three cents, brought them four volumes of a twenty-volume set of The Complete Works of Charles Dickens, a set that, with full-page illustrations, was printed from plates Harper & Brothers had used for older, more expensive sets. The Post’s promotion began in January 1936 and expired on May 16, 1938, two weeks before I was born. And when, eighty-two years later, in the week of June 9, 2020—a week that marked the 150th anniversary of Dickens’s death—I was isolated in my New York City apartment due to the Covid-19 lockdown, it occurred to me that this might be a good time to do what I’d often thought of doing: reread all of Dickens.

The Post was the first newspaper in the United States to offer complete sets of Dickens. This kind of marketing campaign, whose primary purpose was to increase circulation, was known as a “continuity” program, and it originated in England, where a young Englishman, John Stevenson, had used similar promotional methods to help increase the circulation of the London Daily Herald from 350,000 to over a million within a year. In 1936, when he was twenty years old, Stevenson came to New York and worked for The Post. After a spell there, he went on to work for newspapers and department stores in a wide range of cities, including Boston, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Syracuse, and would distribute millions of books, including complete sets of works by Shakespeare, Robert Louis Stevenson, Mark Twain, Honoré de Balzac, Victor Hugo, and Joseph Conrad.

One evening at the beginning of the pandemic lockdown in March, after watching Great Expectations on Turner Classic Movies—the 1946 version, directed by David Lean—I took down my parents’ copy of Great Expectations and found, tucked between the last page and the back cover, a letter addressed to “Dear Reader” from the “Dickens Presentation Department” of The New York Post. “Congratulations!” the letter began:

With the four volumes you have just received you now own MORE THAN HALF of your 20-volume set of the Complete Works of Charles Dickens. And you certainly have every reason to feel especially happy about it. But just stop and think what an imposing array of beautiful volumes you will have on your library shelves when you have placed the last eight volumes beside the twelve volumes you now own!

The four volumes were “among the most important works that Dickens wrote,” the letter continued, after which it gave brief descriptions of each book (Nicholas Nickleby “presents a vivid picture of family life in which love and romance are interwoven with black treachery”), and noted that “the next four volumes now on press are ‘Bleak House,’ ‘Dombey and Son,’ ‘A Child’s History of England,’ and ‘Uncommercial Traveler’… these celebrated works of Dickens described on the other side of this page.” Here, for example, the description of Dombey and Son, a novel with descriptions of a childhood in which the cruelty of parents mark a young boy’s life forever:

This great novel may be briefly described as the rise, fall and decay of the House of Dombey. It is a tragic tale of a delicate and sensitive boy crushed by the brutal selfishness of his father. Among the things longest remembered in “Dombey and Son” are the tenderly drawn pictures of little Paul… In none of his writings is his deep sympathy for childhood more perfectly expressed than in this great book. The lonely, misunderstood Paul Dombey and his sister Florence take their places beside David Copperfield, Oliver Twist and Little Nell as children who will live in our hearts always.

“Here is a library you will treasure not merely today or just tomorrow, but for all time,” the letter ended. “You will own volumes that will distinguish any room and constantly serve as a reflection of your own discriminating taste.”

There was also a description of Our Mutual Friend in another “Dear Reader” letter, in words lifted mostly from Dickens’s first chapter. This was a novel I would first read when I was twenty; though set in a different time and place, it would, like Dombey and Son, vividly conjure up the often mad elements that coursed through my own family as they did through the life of the twenty-year-old heroine of Dickens’s novel, Lizzie Hexam:

A sinister bird of prey seemed Jesse Hexam, crouched in the stern of a dirty row boat, his eyes fixed upon the broad waters of the Thames, his arms bare, his shirt matted, his clothes mud-begrimed. Twilight deepened the shadows cast by the huddled buildings of London, but his gaze did not swerve. His daughter, a girl of twenty, rowing in obedience to his nods, regarded him with fascinated dread. Suddenly he stiffened; the bird of prey had sighted the quarry. A few minutes later behind the boat a body bobbed and lunged. Hexam had found another corpse, the pockets of another drowned man to rifle. It was this grisly livelihood that was reflected in the frightened eyes of Lizzie Hexam.

Throughout my childhood, The Complete Works of Charles Dickens resided behind a glass-enclosed side panel of a mahogany breakfront in the living room of our 730-square-foot Brooklyn apartment. The breakfront, about four and a half feet wide and seven feet high, dominated our small living room, and was filled with my parents’ most precious possessions—Jewish ritual objects, wine glasses, vases, serving dishes, and, in the central glass-fronted cabinet, a half-dozen sets of delicate gold-rimmed demitasse cups and saucers of a kind virtually all my aunts displayed in their breakfronts and china closets.

Advertisement

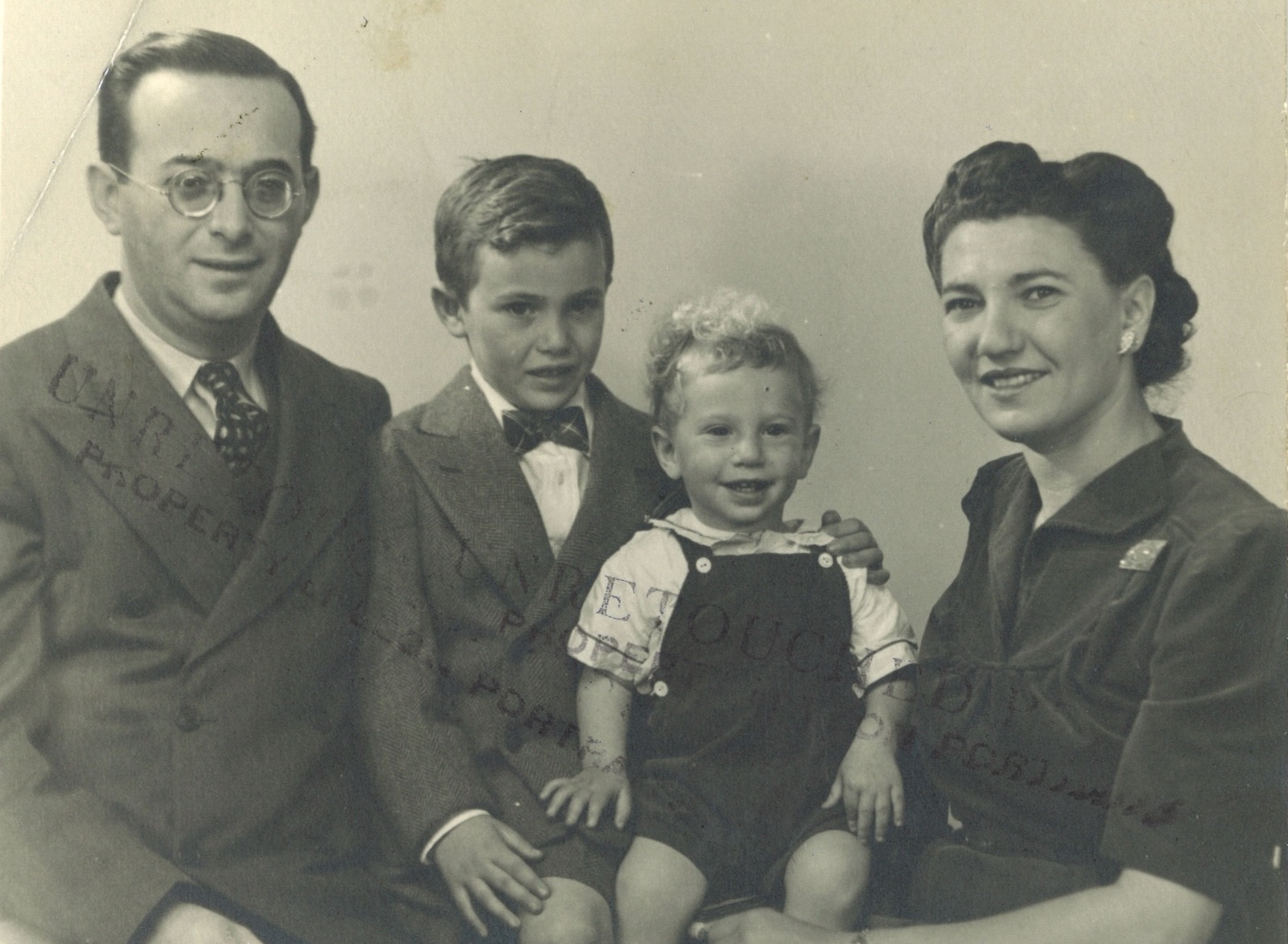

Before I entered kindergarten, and before my only sibling, Robert, was born—he and I were five years apart—my mother sat me down in our living room one afternoon for what she said was going to be “a special occasion.” She unlocked a side panel of the breakfront, took down Great Expectations, and taught me how to open it in a way that would not “break” its binding or “crack” its spine. She asked me to read the book’s opening paragraph aloud to her, which I did, surprised to discover that the main character in a “great” novel had a name as simple as “Pip” (and told the reader so in a sentence I’ve carried with me ever since: “So, I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip”). After that—just the two of us in a moment more peaceful than most I would ever experience with her, and like a movie star—my mother adored being the center of attention, a place she commanded wherever she went by her exceptional beauty and flair for the dramatic—she read and acted out several pages of the novel.

This memory connects to a more familiar one: watching my father, who was totally blind in one eye and legally blind in the other, sitting in front of the breakfront and shielding his good eye from the glare of a stand-up lamp’s light while, at a drop-down secretary contained in the breakfront’s top drawer, he paid bills and worked at his accounts. The secretary had slots for storing bills and letters, cubbyholes and drawers for supplies, and a pale green blotter held in place at its four corners by leather triangles into which my father tucked notes and bills.

Despite his weak vision—his literally cockeyed gaze forever recalling for me the description in Dombey and Son of Jack Bunsby, who had “one stationary eye in [his] mahogany face, and one revolving one, on the principle of some lighthouses”—my father was in the printing business; more exactly, he was what was then called a printing “jobber.” Beginning when I was eight or nine years old, and continuing through my high school years, I would often, on school vacations, go to work with my father, whose “office” was a desk he rented in one of the offices of a printing company on Sullivan Street in Greenwich Village. I would spend the days either going to clients and print shops with him or—my great joy—traveling the subways on my own and picking up orders such as personal stationery, invitations, and circulars from print shops that I either brought to him or delivered for him.

At home, and with a patience he rarely showed at other times, he would sometimes explain what he was doing and why, and I would be astonished that a man who was nearly blind could, and in such a narrow space—the breakfront’s desk was less than six inches deep—not only read the miniscule print in catalogues, but write out, in elegant script, and with bold, clear ruled lines and symbols (for invoices, receipts, order forms)—the “copy” that he (or I) would bring to printing shops where his handwritten and hand-drawn pages would be transformed into stacks of printed matter.

Other than the time my mother and I read to each other from the opening pages of Great Expectations, I don’t recall ever seeing my father or mother actually reading a book of Dickens, and yet, in memory, our family life—a mid-twentieth-century Brooklyn world determined by difficult economic circumstances, inhabited by eccentric, larger-than-life characters, rooted in family feuds about inheritance and money, and steeped in scenes of intense, high drama—seems distinctly Dickensian.

Advertisement

While my father worked at his desk, my mother would, most evenings, find an occasion to go on rants—screaming, sobbing, occasionally banging her head against a wall—about how small and suffocating our apartment was, and about how hard she worked while he “dabbled” at accounts that were never going to pay the rent. On Saturday afternoons, after he came home from synagogue, the rants would become more ferocious. “Look at him—!” she’d cry. “Just look at him, would you?—just look at the way he sits there in the dark doing nothing!”

Our father’s printing business was “a sickness,” she’d declare, and she’d plead with him to shut it down, to file for bankruptcy, and to get a real job—so that she, a registered nurse who’d finished first in her class at nursing school, could stop working nights and sixteen-hour double-shifts at hospitals while also taking on part-time secretarial jobs, directing fundraising campaigns for charities, caring for me and Robert, and still doing all the housekeeping chores that women who did not have to work at full-time jobs performed: shopping, cooking, ironing, sewing, cleaning, etc.

My father would respond by saying that the only thing he hoped for in this life—“Above all, Annie!” he’d cry. “Above all!”—was to be able to do well enough so that she could stop working and our family could afford to move to a larger apartment. And he would proclaim his undying love for her, and declare that he was the luckiest man in the world and one of the smartest—and how did he know this, he’d say—because he’d had the good sense to marry “the most wonderful and beautiful woman in the world!”

To his constant protestations of love, she’d reply, dismissively, “I know you love me,” much in the manner, I’d later think, that David Copperfield’s Emma Micawber repeatedly says of her husband, incarcerated for not having paid his creditors, “I will never desert Micawber.”

In fact, our mother regularly threatened to leave our father. When they thought we were asleep, Robert and I would hear them arguing in the kitchen about getting a divorce, with—the usual script—my mother saying she would “take” Robert and my father could “have” me. Like many couples of their generation who had embattled marriages, our parents stayed together—“stuck it out,” in the idiom of the times—though every few months our mother would leave us with our father and go on weekend getaways to mysterious places called “milk farms” (Did they milk cows, Robert and I wondered. Drink milk? Bathe in milk?). And, once every few years, usually when a family for which she did at-home nursing gave her a cash bonus, she would take cross-country trips, by train, to Los Angeles, where she would stay with cousins for several weeks. Sometimes, too, our father would leave us with our mother, depart for work in the morning with a small suitcase, and stay for several days and nights with the families of one of his brothers or sisters.

*

Our father, born on New York City’s Lower East Side in 1904, was one of nine children (six older brothers and sisters were born in Poland), and our mother, born in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn in 1911, was one of eight (two boys had died, also in Poland, before the family immigrated to the United States). As a result, Robert and I had thirty-seven first cousins, all of whom—except for the son and daughter of an aunt and uncle who had moved to what I thought of as a foreign country, the Bronx—lived in Brooklyn, most of them within walking distance.

After having two sons die within the first two years of their lives, and then giving birth to three daughters (my mother’s three older sisters), my grandmother never forgave my mother for being born. “I needed you like I needed a hole in my head,” she often said to her, and she beat her frequently. When I mentioned this to one of my older cousins, she told me about the time when, as a young girl, she watched her mother also being beaten by our grandmother as, all the while, our great-grandmother kept shouting, “Harder! Harder! Harder!”

My maternal grandparents fought with each other so ferociously—my mother once watched my grandmother lift my grandfather bodily and throw him down the stairs from the second-floor landing of their house—that throughout her childhood she lived with the fear that, as sometimes happened, she’d arrive home to find the police there to break up her parents’ fights.

Her parents separated before I was born and never again lived together. My grandfather had wanted to marry my grandmother’s younger sister but was told by her father that if he married an older sister, he would receive a handsome dowry. My grandfather married the older sister, and in a story that mimicked many of Dickens’s novels—The Mystery of Edwin Drood, The Old Curiosity Shop, and Martin Chuzzlewit, where young men and women rarely get to marry the person they love (at least at first)—my grandfather never received the promised dowry and remained forever bitter about this betrayal. After my grandparents separated, he lived in the Bialystoker Home for Jewish Men on the Lower East Side, where he worked as a baker to help defray fees, sharing with other Jewish men a dormitory-like room in which he had nothing of his own but a narrow iron-frame bed and a small dresser.

My grandmother lived in the three-story building in Williamsburg in which my mother had grown up. Although my grandparents owned the house, my grandmother was its janitor and custodian, scrubbing the hallway floors and staircases, loading the furnace with coal, hauling away the ashes. My mother often told the story of her embarrassment at bringing a friend home from school and finding her mother on her hands and knees in front of the house, repairing the sidewalk with cement.

In 1913, when my mother was two years old, my grandmother gave birth to a boy, my uncle Izzy, who became my grandmother’s favorite; and seven years after Izzy’s birth, she gave birth to a fifth daughter, Evelyn, who, as the family’s pampered “baby,” was spared the physical abuse my grandmother visited on my mother. Evelyn became a nurse, and the mother of four children, two boys and two girls; Evelyn’s husband sexually abused both daughters, and one of Evelyn’s sons, my cousin Martin, committed suicide at the age of nineteen by jumping off the roof of a hospital in Queens. My uncle Izzy passed away in 1954 at the age of forty-one.

Using the promise of bequeathing the house they owned in Williamsburg, my grandparents succeeded in making their six children choose sides in a never-ending war, much like the constant battles in Bleak House that John Jarndyce calls “the family curse.” And so, for many years, my mother’s eldest sister and her brother Izzy did not talk to my mother. Neither did my grandmother and my mother speak with each other for the last eight years of my grandmother’s life. In January 1955, less than a year after Izzy died, my grandmother was found unconscious at the bottom of the cellar stairs in her building. She died a few days later; how she fell remains a mystery. After her death, my mother and her sisters were able to put aside their quarrels, to divide proceeds from the sale of the house equally, and to give an equal share to Izzy’s widow.

*

When people asked why she chose to stay with my father, my mother always said the same thing: “I know he’ll never hurt me.” Yet our father, mild-mannered and withdrawn as he was most of the time, did have temper tantrums during which he’d smash dishes, spit at Robert, and slap me around. If something I’d done or, more often, had not done, displeased our mother—and it was my job, weekday afternoons, to take care of Robert, run errands, clean the apartment, and prepare supper—my father would, like a petulant child, stamp his feet, scream, and strike out at me.

Neither Robert nor I knew at the time what my friend Milton, who lived in the apartment above ours, told me after my father died: that he and his parents several times heard our father screaming that he was going to kill himself—“It’s the end! It’s the end!” he’d cry. “I can’t take it anymore! I can’t take it anymore!”—at which cries Milton’s father would rush downstairs, and bang on the door until my father opened it and let him in.

In the fall of 1958, at the start of my senior year of college, my father, then fifty-four years old, filed for bankruptcy. He wept when he came home from court, talking about the shame he felt for not having repaid friends and relatives who, through the years, had been secretly loaning him money. I knew about these loans because it had been my job to get to the mailbox every day before our mother arrived home from work, take out letters addressed to my father, and sneak them to him when our mother wasn’t around. For her part, my mother one afternoon invited me into her bedroom, and told me about her secret savings accounts (a friend held the bankbooks), in which she was putting away money we’d need when our father went out of business or was unable to work. In the event, following his bankruptcy, my father took a seventy-five-dollar-a-week job as a clerk in a stationery store in the Wall Street district.

That my mother might become seriously ill and be unable to work seemed impossible to me, for no matter her constant threats that “someday soon” she was going to collapse and leave us to fend on our own, she seemed indestructible. In fact, other than times she had migraines—for which she would lie in bed, the room dark, with a cold compress over her eyes; or take enemas, the olive-drab rubber douche bag and tubes forever hanging from the shower curtain rod above our bathtub—I have no memory of ever seeing her sick.

When I was nine years old, I used my small savings to buy her a scented Valentine’s Day card. She threw it in my face. “Anyone can buy a card,” she said. “If you really loved me, you would have made me a card.” As painful as it was to have her withdraw her love from me, or to watch her humiliate our father, I remained, always, in awe of her strengths: her tireless capacity for work, her boundless energy and stamina, her shameless and dogged pursuit of anything and everything she desired, and, most remarkable perhaps, given her vindictive streak, the sheer joy she took in life. At family gatherings, she would hold forth with tales of doctors, patients, and youthful adventures, tell off-color jokes, and laugh so hard at stories she and others told that I was frequently astonished, and thrilled, to hear her cry out, “Stop already—stop before you make me wet my pants!”

To the world that existed beyond the four rooms of our apartment, she was forever smiling, vivacious, outgoing, and generous. She was also forever touching, hugging, and kissing everyone, not only her friends and relatives, but also my friends, and even strangers with whom she’d initiate conversations in stores, in subway stations, and at bus stops. On weekend afternoons, despite my father’s complaints that she was giving the men washing their cars in the backyard “a free show,” she often paraded around the apartment in nothing but her panties.

To the boy and young man who craved her approval, gratitude, and affection—all of which I did receive, if generously mixed with their opposites—she was to me what she was to my father: the most wonderful and beautiful woman in the world, and I took strength from her strengths. In my determination never to be a failure like my father, so as never to visit on a family of mine the suffering his inability to earn a living had inflicted on ours, I identified with my mother’s frustration, her rage, her insatiable need for love and praise, and the ways they fueled the fierce will that fired her ability not only to survive and to enable our family to survive, but to thrive.

“I want what I want when I want it!” she regularly announced, and as sweet and charming as she could be when being sweet and charming suited her purposes, she could also be venomous and ruthless. She took as much pride in her ability to drive down the price of a used car or a new dress, or in the twenty-five-dollar commission she earned for persuading a family to send its child to the summer camp we went to, where she worked as camp nurse, as she did from forcing our father into bankruptcy, an event that would come painfully to mind when, years later, I read about the evil Mr. Smallweed in Bleak House, doing the same to the disgraced and innocent Mr. George.

When my brother Robert was sixteen years old, she became alarmed by what she considered his bizarre eating habits, weird combinations of clothes, dangerous “beatnik” friends, and erratic schoolwork (exceptionally high grades in some subjects, exceptionally low grades in others). She decided he was “sick,” and had to be put away permanently in a mental hospital. When she had him evaluated by the director of Adolescent Services at Kings County Hospital, the doctor told her not to waste time with psychotherapy: Robert would indeed need to live in a mental institution for the rest of his life and should be placed in one immediately. “See!” she said, when she presented us with the news. “You thought I was the crazy one, but I wasn’t. Oh no! You were all against me—all three of you—but I persevered and guess what? I was proven right!”

In some of his essays, though not in his novels, Dickens wrote about the deplorable conditions he found in London’s lunatic asylums—conditions not unlike those I’d find in the mental hospitals in which my brother was incarcerated. But Dickens’s interest was not only that of a social reformer: while pursuing an affair with the actress Ellen Ternan, he attempted to have his wife committed to one of these institutions.

When I asked Robert to explain what had happened during his evaluation at Kings County, he laughed and said he’d wanted to find out what the inside of an insane asylum was like, so he’d given the doctor answers he knew he was looking for. I congratulated him on passing the admission test, but remarked that once he was inside, it might not be so easy to get out. Robert saw my point, and agreed to go for a second evaluation. With my friend Milton’s help—he’d recently finished training as a psychologist—I was able to have Robert evaluated by the director of Adolescent Services at Bellevue Hospital. This doctor concluded that Robert did not need to be hospitalized, and did not even need psychotherapy.

Two and a half years later, however, after winning a Regents Scholarship from New York State and completing his freshman year of college at the City College of New York, Robert did have a major psychotic episode. He was admitted for six weeks to the psych ward of Elmhurst Hospital, in Queens, and then, for a year and a half, at reduced fees my mother succeeded in obtaining, in a private psychiatric hospital. He recovered, completed a second year of college, but suffered a further breakdown, after which he spent the rest of his life—another fifty years—in and out of psychiatric hospitals and halfway houses. In 1973, when he was incarcerated on an insulin coma ward of the notorious Creedmoor Psychiatric Hospital, our parents moved to a retirement village in West Palm Beach, Florida. Robert was then twenty-nine years old; our father died three years later without ever seeing him again. Our mother lived for another thirty years. During that time, she saw Robert twice.

*

During my undergraduate years, I completed two unpublished novels, and in the five years that followed I completed six more books (five novels, one nonfiction book). By the time I had a novel accepted for publication, in 1965, when I was twenty-seven, I had accumulated more than two thousand rejections.

I’d started, in fact, when I was eight years old, writing out a seventy-page novel that my mother typed up for me. On the page the words came out, gloriously, half-red and half-black. For several months, on Monday mornings, I read a new chapter of the novel to my fourth grade class at PS 246, and I can still recall the joy I felt when, at recess and lunch, my classmates would crowd around and ask me to tell them what was going to happen next, to which I’d reply that I never knew until I sat down and began writing.

Between the time I wrote the seventy-page novel, and my graduation from high school, I don’t recall having any thoughts about becoming a writer. When I entered Columbia in the fall of 1955, I listed architecture and advertising as my two career ambitions. In my freshman year, however, I was away from home for the first time in my life, commuting two hours a day by subway and staying on campus until late in the evening. By the end of that year, I’d begun reading voraciously again, in the way that I had as a child; and I began writing short stories and conjuring up novels.

Then, shortly before my nineteenth birthday, in 1957, I checked in at Columbia University’s Student Health Service about some swollen glands that had lingered on after a sore throat and subsequently underwent a biopsy. Diagnosed with a type of lymphoma that, I learned later, was considered the first stage of Hodgkin’s disease, I received radiation treatment. At the time, what I was told was that the lymph nodes, removed by surgery, were “benign” and the radiation “a precaution.” The true implications of the diagnosis were kept from me, but part of me believed I did have cancer; convinced that I had only a year left to live, I decided it was time to do what I’d been longing to do. After my parents and Robert were asleep, I’d go into our kitchen, put my typewriter on towels to muffle its click-clacking, and work on what would become my first real novel. Two years later, still in remission from cancer—as I am, all these years later—I wrote a second one.

Then, as now, when people asked what inspired me and kept me going, I said what many writers have said: that my desire to become a writer derived from my childhood love of reading. And then I’d talk about how the happiest hours of my childhood were those I’d spent reading novels by Dickens from our family’s set of his complete works, and about how I’d dreamed of the day when I’d have a shelf of books with my name on them that would be as wide as that twenty-volume set. It would be many years, and many books, later, however, before I realized the effect my mother’s fussing so much over the book I wrote when I was in the fourth grade—calling me her “little genius,” bragging about it, trying to get it published—had had on me. To protect what would become the dear and beloved companion of my life, writing, and keep it from being taken away from me, I had apparently buried my desire to be a writer so far underground that even I didn’t know it existed.

When I was in the act of writing, I felt capable of making sense of a world that often seemed without sense, and this experience served, as reading novels and stories had, to protect me from the currents of madness that swirled around me, and that sometimes coursed within me. While I was writing, or simply reading, I could for a while shut out such feelings and be transported to a world that, no matter how terrifying, mad, strange, or cruel, was not the one I actually lived in. That world in writing did not have the power to hurt me, drive me mad, or take away what was precious to me.

*

When my parents moved to Florida, they had the complete set of Dickens and the mahogany breakfront shipped to me in North Hadley, Massachusetts, where I was then living and raising my own family. In 2003, when I moved from there to an apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, I shipped the breakfront to my daughter, Miriam, who lived in Falls Church, Virginia. But I kept the books.

And when, a few weeks ago, I took down from my shelves Dickens’s Great Expectations and found the “Dear Reader” letter, I was transported again—as I’d been so often while reading Dickens—to that mid-century world of my childhood—that world in which first-generation immigrants like my parents aspired to become part of the greater American experience that existed beyond our cramped apartments and struggling families, and to do so, in part, by owning books by “great” writers and keeping them “in a place of honor” that “distinguished” their owners for their “discriminating taste,” and gave them the gift of a “library” they could “treasure… for all time.”

Now, in the spring of 2020, isolated in my New York City apartment, I took down The Pickwick Papers, Dickens’s first published novel, and began reading. But as the prospect of rereading all of Dickens beckoned, I thought, too, of Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust. In that novel, Tony Last, an English country gentleman, goes on an expedition in search of a supposed lost city in the Amazon rainforest. On the journey, he falls ill, and is cared for by Mr. Todd, a British Guianan who lives in a remote part of the jungle. Although he is illiterate, Todd owns a set of the complete works of Dickens, and asks Last to read to him—first Bleak House, then Dombey and Son, Little Dorrit, Oliver Twist, and Nicholas Nickleby. Meanwhile, a rescue party sent out to search for Last approaches. Todd conceals Last after drugging him into a comatose state, and tricks the would-be rescuers into believing that Last is dead. When Last comes round, he realizes there is no escape: he has been condemned to spend the rest of his life in the jungle reading Dickens to Todd.

“Let us read Little Dorrit again,” Todd says, near the end of A Handful of Dust. “There are passages in that book I can never hear without the temptation to weep.”