News summary:

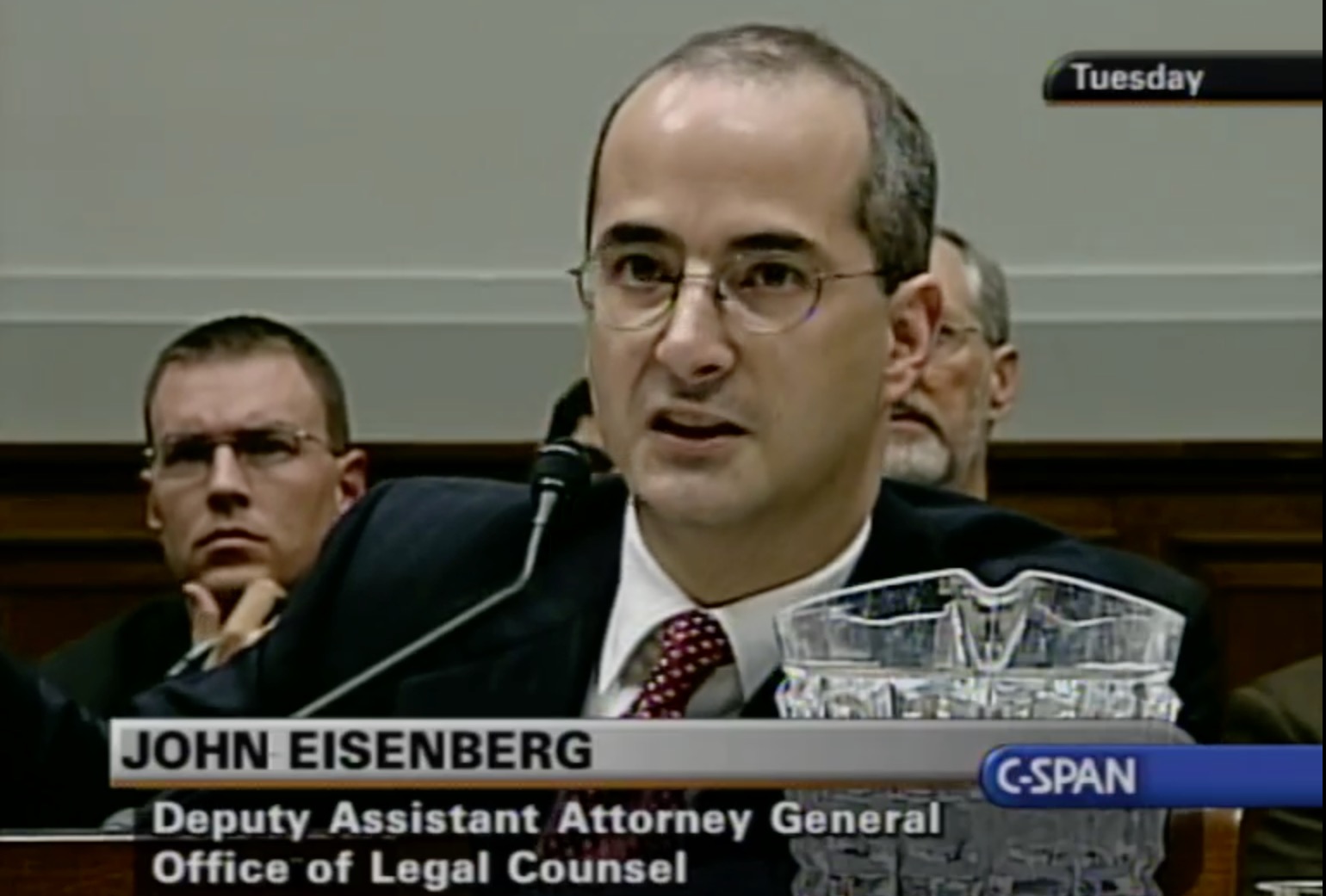

In early 2017, Deputy Counsel to the President John Eisenberg pressed a senior Justice Department official to tell him whether anyone close to President Trump was the subject of electronic surveillance as part of a continuing federal criminal investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential campaign. That enquiry appears to have violated the Trump White House’s own official policy restricting its officials from discussing open criminal investigations with Justice officials, according to declassified FBI records and interviews documenting this previously unreported incident.

The White House policy that Eisenberg violated was devised by his own immediate superior, then-White House Counsel Don McGahn, who only five weeks earlier had distributed a memorandum outlining the policy to the entire White House staff. Remarkably, then, it was McGahn himself who asked Eisenberg to find out about whether the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court had approved warrants to eavesdrop on people close to the president.

Trump personally directed his aides to learn whether this surveillance was occurring, improperly interfering with an investigation that involved him and his aides. This raises the possibility that actions taken by those party to Eisenberg’s effort could be an attempt to obstruct justice.

On the afternoon of March 4, 2017, Mary McCord, who was the head of the Justice Department’s National Security Division, received an unexpected, urgent phone call from White House official John Eisenberg, the legal counsel to the National Security Council (one of several titles he holds in the White House). Earlier that morning, President Donald Trump had posted no less than four tweets claiming, without evidence, that his predecessor, Barack Obama, had personally ordered the wiretapping of Trump to spy on him and his presidential campaign.

The White House refused to issue any statement about what underlying factual basis there might be for the president’s allegations, most likely because, as became apparent, there was none. But behind the scenes, according to a former senior administration official, the president then ordered White House Counsel Don McGahn to discover whatever evidence he could, after the fact, that might lend even some credence to Trump’s claims. Although Trump’s instruction meant violating the ethics policy McGahn himself had drawn up on January 27, he chose to carry it out by delegating the task to Eisenberg.

Trump was unambiguous in asserting that he had personally been wiretapped, that the electronic surveillance had taken place at Trump Tower, that its purpose was to spy on his presidential campaign, and that President Obama had ordered this political espionage. At 6:35 AM, the president tweeted: “Terrible! Just found that Obama had my ‘wires tapped’ in Trump Tower just before the victory. Nothing found. This is McCarthyism.” At 6:49 AM: “Is it legal for a sitting President to be ‘wire tapping’ a race for president prior to an election?” At 7:02 AM: “How low has President Obama gone to tapp my phones during the very sacred election process. This is Nixon/Watergate. Bad (or sick) guy!”

McCord, when later questioned by the FBI, said Eisenberg asked her, “What would we have to do to find out if this evidence exists?” As she explained to the FBI, McCord said she’d found Eisenberg’s request highly unusual, improper even. She asked Eisenberg if he was asking her “if this coverage exists,” meaning the alleged wiretapping. Apparently wary of the task at hand, Eisenberg sheepishly replied: “I guess so.”

According to a since declassified FBI report recounting what McCord told agents in an interview:

McCord asked Eisenberg to tell her exactly what he was asking for. Eisenberg told her he would send her an article, and he wanted to know if she could tell him if it was true. McCord told Eisenberg she would get back to him. McCord doesn’t recall if he sent her an article or if she looked it up on her own, but she recalled reading an article from the Breitbart website on Trump’s statements about Trump Tower being tapped.

The Breitbart article, which had been the sole basis for Trump’s claims, was based on comments that the conservative radio host and Fox News personality Mark Levin had made on his show. But Levin, who is known for his preoccupation with conspiracy theories, produced no credible evidence to support his allegations. Levin’s primary source for his extraordinary charges was an article on a right-wing US and UK news site, Heat Street, written by one of its founders, Louise Mensch, a former Tory member of the British Parliament turned journalist, who has at times also trafficked in conspiracy theories. In short, the nation’s best-known conspiracy theorist (President Trump) was quoting another (Levin), who in turn was quoting a third (Mensch).

Advertisement

Levin claimed to have reams of other “evidence,” alluding to speculative reports that the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, often known as the FISA Court (after the 1978 act of Congress that established it), had authorized the electronic surveillance of aides to Trump as part of the FBI investigation into Russian interference with the 2016 presidential election. Even if any of these accounts had been true, that someone associated with Trump had been subjected to such electronic surveillance, as part of a legitimate counterintelligence or criminal investigation, that would hardly mean that Trump himself had been targeted; neither would it mean that it had any purpose to spy on his campaign; nor that President Obama had ordered it. Such eavesdropping is a legitimate, court-approved, and legal investigative tool.

It was perhaps with good reason, then, that McCord told the FBI that “she never heard back from Eisenberg on that matter.”

But Eisenberg’s efforts, in fact, continued. He next phoned Bradley Brooker, the acting general counsel for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and asked Brooker if he knew of any information that President Trump had been wiretapped, according to declassified FBI records as well as a person who spoke directly with Brooker regarding the matter. Brooker, like McCord, had no information to provide. Troubled by the inquiry—and concerned that he, too, was being drawn into an inappropriate situation—Brooker tactfully sidestepped further discussion of the matter.

Recounting Eisenberg’s entreaties to her and Brooker, McCord volunteered to the FBI that she “considered it inappropriate for Eisenberg to ask for information of that nature.”

This previously unreported episode poses serious ethical and legal issues for the Trump White House. Eisenberg’s query to McCord almost certainly violated the Trump administration’s own ethics rules prohibiting White House officials from seeking out information from either the Justice Department or the FBI relating to ongoing criminal investigations. (White House officials are allowed to make such inquiries only for a small number of narrowly delineated exceptions, of which this was not one.)

But the episode also raises even more troubling questions about whether Eisenberg’s fact-finding was part of a scheme to undermine the investigations by the Justice Department and FBI into Russian election interference; that might be construed as an obstruction of justice. Had Eisenberg obtained information about possible FISA surveillance of people in Trump’s circle, and provided the president or anyone else in the White House with that information, the individuals involved would almost certainly have taken measures to defeat the eavesdropping; that scenario would entail hampering a federal investigation. And if the president or a White House official had gone public about such highly classified eavesdropping, that would have also interfered with the DOJ’s and FBI’s Russia investigations, by tipping off possible surveillance targets. To expose or stymie the FISA warrants in such a manner would almost certainly have been an obstruction of justice.

*

The Trump administration’s own policy prohibiting contacts between the White House and the Justice Department and FBI was a continuation of bipartisan practices and policies of no fewer than six successive previous presidential administrations, dating back some forty years. McGahn drew up the Trump administration’s policy only days after coming into office; on January 27, 2017, he sent a memorandum articulating that policy to all White House staffers.

These prohibitions had their roots in the era of post-Watergate reforms. One of the ways Richard Nixon and his top aides were able to contain the Watergate investigation for so long was because Nixon and his White House counsel, John Dean, had access to confidential FBI reports and other information detailing exactly what witnesses were telling investigators—often within just days of their questioning. In this way, Nixon and his top aides were able to stay one step ahead of investigators by concocting cover stories, often perjuriously but credible. The federal grand jury that investigated Watergate found evidence that Nixon’s access to this inside information was central to the cover-up. That effort ultimately failed because Nixon had been taping himself, thus memorializing conversations with his own aides as they obstructed justice.

Although Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, apparently did not add to the doctrine, a senior Justice official told me that stringent rules written by former Attorney General Eric Holder were considered still in effect. As for McGahn’s January 27 memorandum, it also set out clear and explicit guidelines:

These rules exist to ensure both efficient execution of the Administration’s policies and the highest level of integrity with respect to civil or criminal enforcement proceedings handled by DOJ. In order to ensure that DOJ exercises its investigatory and prosecutorial functions free from the fact or appearance of improper political influence, these rules must be strictly followed. [All emphasis per the original.]

McGahn’s memo laid out one exception to such inquiries for national security purposes. One of Eisenberg’s three titles in the Trump White House is that he is deputy counsel to the president for national security affairs. Arguably, Eisenberg might be an official with legitimate grounds to seek such information. The portion of McGahn’s memo regarding “National Security Exceptions” says in part:

Advertisement

Frequent communications between the White House and DOJ will be necessary on matters of national security and intelligence, including counter-terrorism and counter-espionage issues. Accordingly, communications that relate to urgent and ongoing national-security matters may be handled by specifically designated individuals… This exception does not relate to a particular contemplated or pending investigation or case absent written authorization from the Counsel to the President. [Emphasis added.]

The purpose of that policy (and detailed rules attached to it) prohibiting such contacts between the Justice Department and the White House is precisely to prevent the politicization of the federal law enforcement agencies. A 2017 report by the advocacy group Protect Democracy, argued that “political influence or interference in law enforcement has been a clear hallmark distinguishing authoritarian regimes from true democracies around the globe.” This yardstick, the degree to which a country’s prosecutorial apparatus has been politicized or not, is also applied by the US State Department in foreign relations when considering whether to designate a nation as democratic or authoritarian.

A 2007 Justice Department memo says that the prohibitions are necessary for “ensuring that there is public confidence that the laws of the United States are administered and enforced in an impartial manner.” Michael Bromwich, a former federal prosecutor for the Southern District of New York and former Justice Department Inspector General, has called the prohibition of such contacts regarding a continuing investigation “an inviolable rule.” (As a private attorney, Bromwich is currently suing the Trump administration on behalf of former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe for wrongful termination.)

Miriam Baer, a former prosecutor for the Southern District of New York and now a professor at the Brooklyn Law School, told me that “the reason prosecutors and investigators adhere so strongly to no-contact rules and independence norms” is that without them the “government remains keenly vulnerable to claims that it is acting with partisan motives or in bad faith.” And she added: “The primary way to vanquish these claims is to be able to say… that career prosecutors called the shots and did so independently without political pressure.” The alternative is that the Justice Department, FBI, and the entire federal criminal justice system lose their legitimacy with the public.

In this case, it is unclear whether Eisenberg told McGahn explicitly whether he was going to reach out to McCord, Brooker, and possibly other officials. Logically, however, there would be no other way for Eisenberg to learn this information without making such enquiries. For a senior federal law enforcement official like McCord, the existence of such FISA surveillance would be considered to be among the most sensitive law enforcement information, even more so because it related to a current investigation. For a national security official like Brooker, such information would also be considered to be among the government’s highest classified intelligence.

If Eisenberg was to abide by McGahn’s own policy, he ought to have obtained written authorization from McGahn before he questioned McCord. It is doubtful he did so. Since the instruction to seek information about possible surveillance of the president’s associates for a pending investigation came from McGahn himself, it must be concluded that both he and Eisenberg knew the task violated the very standards McGahn had just promulgated.

*

When Eisenberg queried McCord and Brooker about possible FISA surveillance, it was long known that President Trump’s former campaign manager, Paul Manafort, was under federal criminal investigation for consulting work he had performed for a pro-Putin then-president of Ukraine and his Party of Regions; at the same time, Manafort was also under investigation for whether he had encouraged or conspired to help Russia covertly interfere in the 2016 presidential election on behalf of Trump. The New York Times reported on February 14, 2017, that “American law enforcement and intelligence agencies intercepted” phone conversations of several Trump campaign members and Trump associates, identifying Manafort as “one of the advisers picked up on the calls.”

To the frustration and consternation of the president’s aides and the White House attorneys, President Trump continued to speak regularly to Manafort over the phone even after he’d fired Manafort as his campaign manager in August 2016; and the contact continued long after Trump was president.

If Manafort was indeed the target of electronic surveillance, those around Trump feared, federal law enforcement officials might overhear his conversations with the president. As the Times reported in March 2018, Trump’s personal attorney dangled pardons to Manafort and former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn; the aides feared that Trump himself might be overheard making some improper proposal. McGahn and his colleagues thus had their own incentives to find out whether Manafort or other Trump aide was a target of electronic surveillance. But if they relayed that information to Trump, or anyone else under investigation, compromising such surveillance, that conduct might also constitute an obstruction of justice.

The concern of President Trump’s most senior advisers that there might be FISA-authorized surveillance of his aides is also demonstrated by a conversation that then-FBI Director James Comey had with then-White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus, on February 8, 2017. In a query similar to the one that Eisenberg made of McCord and Brooker little more than three weeks later, Priebus wanted to know if there was FISA surveillance of Trump’s then-National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. According to contemporaneous notes Comey made of the conversation, Priebus asked him outright: “Do you have a FISA order on Mike Flynn?” (It is unclear from Comey’s notes precisely how he answered the question, but Comey did tell Priebus that he felt uncomfortable about the chief of staff ’s ignoring the rules forbidding such enquiries. He did advise Priebus that it “illustrated the kind of question that had to be asked and answered through established channels.”)

At the time, Priebus, McGahn, and Eisenberg (later joined by Vice-President Mike Pence) were conducting an informal inquiry into whether Flynn had lied to Pence, other White House officials, and perhaps also to the FBI, about conversations he had had with the then-Russian ambassador to the US, Sergey Kislyak. During phone conversations with Kislyak on December 29, 2016, Flynn had counseled Kislyak and Russia not to escalate a dispute with the US after the outgoing Obama administration imposed sanctions on Russia for interfering in the 2016 presidential election. Flynn had told Pence, the FBI, and others, that he never discussed sanctions with Kislyak. But the conversations between the two men were intercepted by US intelligence agencies, demonstrating that Flynn had lied.

As I first reported in 2018 for the NYR Daily, Eisenberg was the first White House official given permission to read the highly classified transcriptions of intercepts of the conversations between Flynn and Kislyak. He thus learned that Flynn had lied to the White House and FBI on February 2, 2017. Priebus, McGahn, and Eisenberg subsequently learned from DOJ and FBI officials that Flynn’s call had been overheard because American intelligence agencies routinely surveil foreign diplomats in the US especially those of regimes that are considered hostile to the United States, like Russia. But President Trump and senior aides still harbored fears that Flynn might also have been a surveillance target through a FISA warrant, according to a former senior White House official who interacted with Priebus and McGahn at the time. Hence Priebus’s question to Comey six days later.

On February 10, Pence, Priebus and McGahn also read the classified transcripts in the White House Situation Room. All of them came away convinced that Flynn had lied to everyone and had to go. Faced with being fired, Flynn resigned on February 13. The next morning, the president spoke alone to Comey in the Oval Office. Trump then allegedly pressured Comey to shut down the FBI’s investigation of Flynn—as Comey recorded, the president told him: “I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go.” Not long after, on March 3, Breitbart published the story that Trump relied on to accuse the government of targeting one or more of Trump’s aides with electronic surveillance in his tweetstorm the following day. And it was later on March 4 that Eisenberg pressed McCord for information about potential FISA surveillance of Trump associates.

Two additional episodes around this time adds suggestive circumstantial detail. On March 9, five days after Eisenberg pressed McCord about electronic surveillance of the president’s aides, an assistant to President Trump placed a call to the then-US attorney for the Southern District of New York, Preet Bharara. Bharara refused to take the call, noting that it would be a violation of longstanding policies—endorsed, of course, by McGahn’s January memo—prohibiting direct communications between federal prosecutors and the president and White House staff. The next day, the president ordered the mass firing of forty-six US attorneys, holdovers from the Obama administration. Among them was Bharara, but unlike his colleagues, Bharara had met with President Trump at Trump Tower during the transition—at which time Trump told Bharara that he could stay on in his post.

The lawyer and writer Artin Afkhami, who has kept a timeline about Trump’s potential obstructions of justice for the website Just Security, has noted that “Because Bharara served as US attorney of the SDNY, his jurisdiction included Trump Tower, and he would likely have known whether Trump Tower had been wiretapped by federal investigators as Trump claimed.” Because Trump and Bharara never spoke on March 9, we cannot know why Trump asked to speak to him.

Unable to get McCord and Brooker, or any other executive branch official, to tell them if there were any FISA warrants on people close to the president, the White House Counsel’s office turned to the legislative branch. On March 10, Representative Devin Nunes, Republican of California, then the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, demanded that the Justice Department turn over any information it had regarding FISA warrants.

Then, on March 22, Nunes held a press conference to announce there might be some truth to the president’s claims. He alleged that “members of Trump’s transition team, including the president himself” had been swept up in the electronic surveillance of others, although he presented no evidence to support his claims. Nunes claimed that this information was provided to him by a principled whistleblower, and that Nunes had considered it so explosive, that he’d immediately gone to the White House to brief President Trump about it in personally.

It did not take long before his ruse was exposed, however. The information had been actually been provided to Nunes at a late night meeting at the White House, and the briefing came from Trump’s own top aides—among them Eisenberg. This bizarre episode reinforces the impression that all involved were engaged in a political scheme to provide a post hoc rationale for Trump’s tweets—a scheme that very obviously risked interfering with, and potentially obstructing, a federal criminal investigation.

Despite the fears of President Trump and those close to him that they had been subjected to a wiretap, or overheard on one, in the end, only a single campaign aide, Carter Page, turned out to have been the subject of electronic surveillance approved by the FISA court—eavesdropping that only began in October 2016, a month after Page had left the campaign. (In a highly critical report, released in December 2019, the Justice Department’s Inspector General criticized that surveillance, finding numerous “significant inaccuracies and omissions” by the FBI in the FISA applications relating to Carter Page.)

*

The import of all this is that if the president, his chief of staff, or anyone else in the White House sought such information with the intention of influencing or affecting the outcome of the government’s Russia investigation, that might constitute an obstruction of justice. The threshold for a prosecution for obstruction of justice is justifiably high. It is not enough for prosecutors to prove that someone “endeavors to influence, obstruct, or impede” a criminal inquiry; they must prove that this person did so with “corrupt” intent. A potential defendant’s demonstrable motivations are therefore central to any decision to charge.

If Eisenberg had learned of evidence of FISA surveillance and turned it over to others who then used it to defeat the investigative tool, Eisenberg might argue he did not violate the law because his motivation was to find evidence to support the president’s allegation of Obama administration espionage, not to obstruct justice. But Eisenberg’s efforts clearly disregarded the spirit, if not the letter, of the law. And he would have known that they defied the rules set by his own boss, White House Counsel McGahn. Whatever defense Eisenberg might mount, he surely had the expectation that his actions might lead, at a minimum, to the exposure of a legitimate tool of law enforcement in such a way that would have obstructed a federal criminal investigation.

In spite of his knowledge of McCord’s account of this matter, Special Counsel Robert Mueller did not investigate it further. The Mueller Report itself makes no mention at all of this episode—which was, ironically enough, uncovered in the Barr Justice Department’s motion in federal court to vacate Michael Flynn’s guilty plea for lying to the FBI. McCord’s interview with the FBI was included in that filing as one of numerous exhibits, apparently because the Justice Department hoped it might undercut Flynn’s prosecution for unrelated reasons. The document went unremarked; its existence is revealed here for the first time.

This lapse by Mueller is a further example of that seriously flawed investigation. The special counsel declined to subpoena the testimony of the president. And as I reported for the Daily, Vice President Pence was a crucial potential witnesses for the investigation of whether Trump obstructed justice. Even though Pence agreed to be questioned, Mueller never availed himself of the opportunity. When John Dowd, an attorney for President Trump, as well as attorneys for Manafort and other Trump aides, inadvertently voided claims of attorney-client privilege by their conduct, Mueller could have compelled their testimony. Yet he never sought to do so.

The missteps of Mueller, though, are not the last word on the matter. To be sure, if Trump is re-elected, it’s inconceivable that the Barr Justice Department would investigate this newly uncovered possible obstruction of justice. But if Joseph R. Biden were elected, his new attorney general would be empowered to investigate this new matter, along with other instances of possible obstruction of justice by President Trump uncovered by the special counsel.

Biden has made clear that he would step away from any decision to charge Trump because to do so would to engage in the same type of abuse of his high office that Trump has engaged in: “I would not dictate who should be prosecuted or who should be exonerated… That is not the role of the president of the United States,” he has said. Instead, he would defer to his attorney general and the nonpolitical career staff of the Justice Department on this question: “If that was the judgment, that he violated the law and he should in fact be criminally prosecuted, then so be it.”