Waitress, Teresa Gallant catering, Mexico, Maine

Snow shoveler, Mexico, Maine

Babysitter, Mexico, Maine

Waitress, Goody’s, Rumford, Maine

Pizza and sandwich maker, Maddy’s Pizza, Mexico, Maine

Pizza and donut maker, Four Corners, Rumford, Maine

Newspaper deliverer, Lewiston Daily Sun, Mexico, Maine

Daycare caregiver, Beloit, Wisconsin

Typist of student papers, Beloit College, Beloit, Wisconsin

Fall school shopping, 1982, the Auburn Mall, Maine. I spied a pair of dark denim Jordache jeans, white stitches bolting across one back pocket. On the other pocket, an embroidered horse head, its mane billowing in an imagined wind. They looked fast, these pants, the hipless women in the ads modern, confident, sultry, even though they were usually clamped onto a man. “You’ve got the look I want to know better…the Jordache look,” the company advertised in a breathy chant. I wanted that look.

I placed the pair into our shopping cart.

“I’m not buying those,” my mother said, flicking the twenty-six dollar price tag.

My face collapsed. My mother, who once said, I’d spend my last dime on a beautiful dress, sensed my desperation. “If you get a job, then you can buy any clothes you want,” she offered, putting the jeans back on the rack.

Reader, I got a job.

The following weekend, I showed up at the Knights of Columbus hall in Mexico, Maine, where my two older sisters were working a wedding for Teresa Gallant, the caterer who worked all the parties in our small, rural mill town. Her potato salad was renowned, as were her wages, which were as generous as the tips she split evenly among her staff. I asked Teresa if she could use my help.

“I am short-staffed today,” she said, in her clipped French-Canadian accent, while my sisters bolted back and forth to the kitchen. “I have a few rules: don’t touch your face or your hair. Serve from the left, pick up from the right. Don’t socialize with people you serve. The rest you can learn along the way.” She looked down at me, her glasses at the edge of her nose, her grand gray hair nested smoothly in a hairsprayed bun. “Now go and change.”

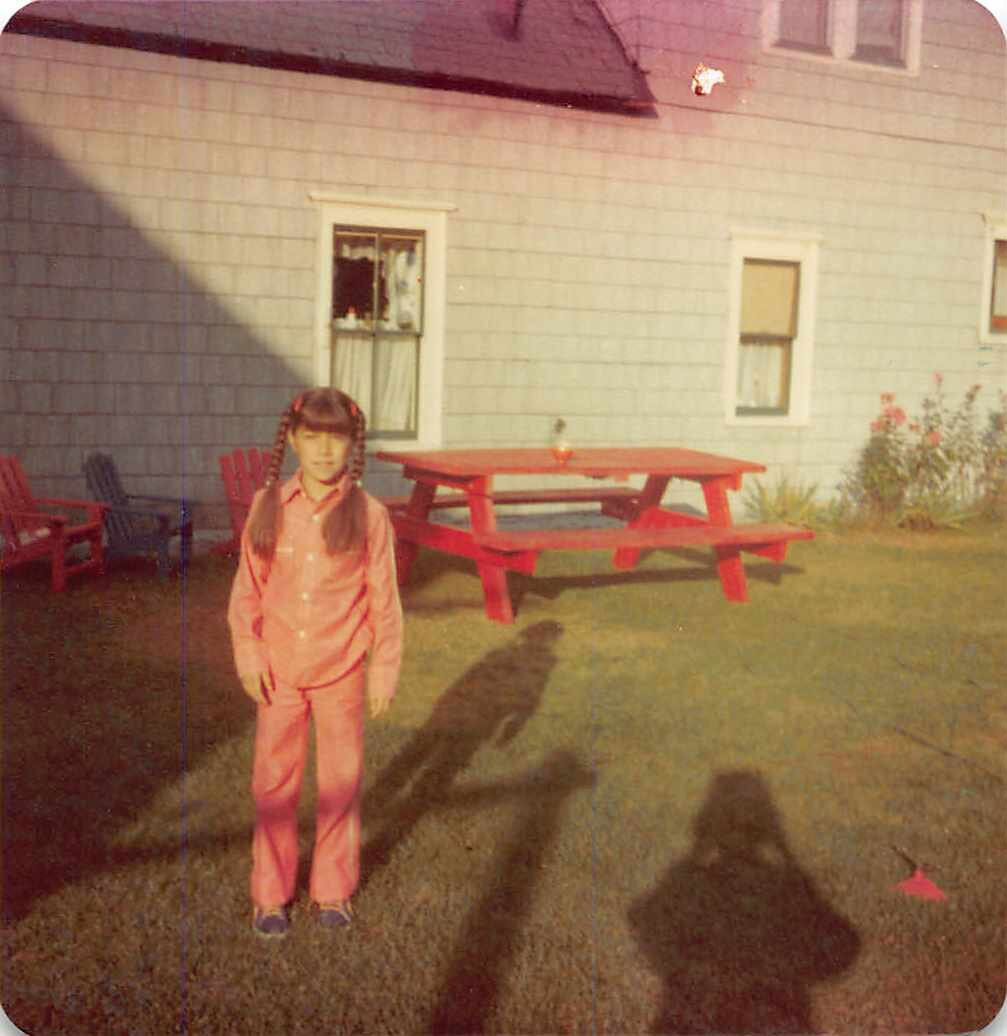

I sped home, just a few doors down, snatched my sister’s extra uniform—a white, polyester zip-front dress—pinned my hair back, and, in less than ten minutes’ time, re-presented myself to Teresa. I was fifteen.

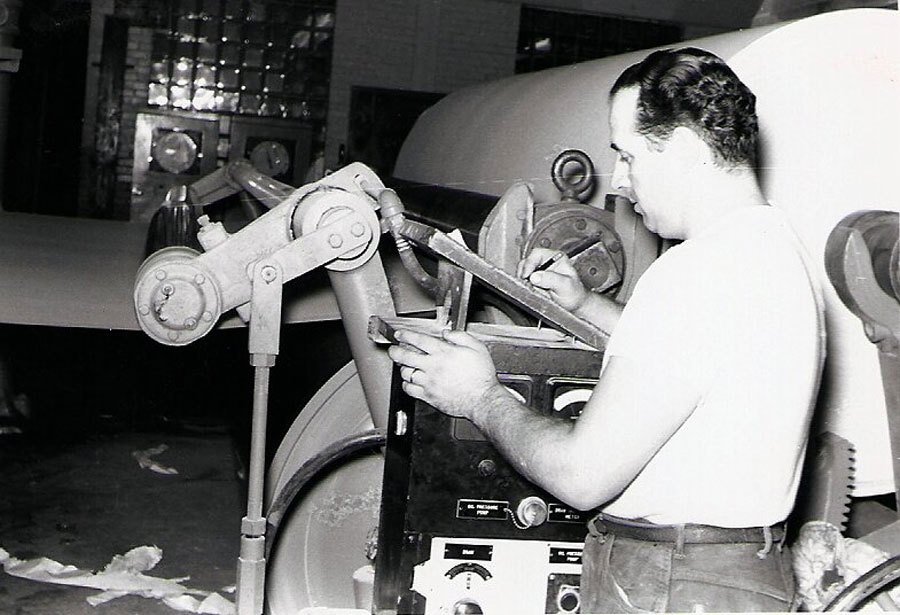

I learned a lot about work from Teresa: don’t be late, mind your own business, hustle, don’t expect praise for doing what you’re paid to do. Breaks and raises were earned, not expected. Don’t be a miser in service or cheerfulness. Once, as I rushed to serve a plate of roast beef, she said, without even looking, “No food should spill over the edge of the plate.” Keeping within boundaries was one of the main job descriptions.

It was hard physically to keep up with Teresa and her foot soldier, Yvette, who micro-bossed us around while Teresa mixed vats of mayonnaise and celery into heaps of parboiled chicken, tossing it with her hands, sampling as she went. Sometimes she even asked us to taste it, as if our opinions mattered. When I’d get home, I’d soak my feet and munch on the leftover salads I’d served partygoers earlier in the day. I liked the feeling of sore limbs and chapped hands, scrubbed raw by Teresa’s insistence that cleanliness was in direct proportion to duty. Being tired meant I was earning money, and if I was earning money, then I was of value not only to her but to myself. It was a closed loop, all within my own capacity.

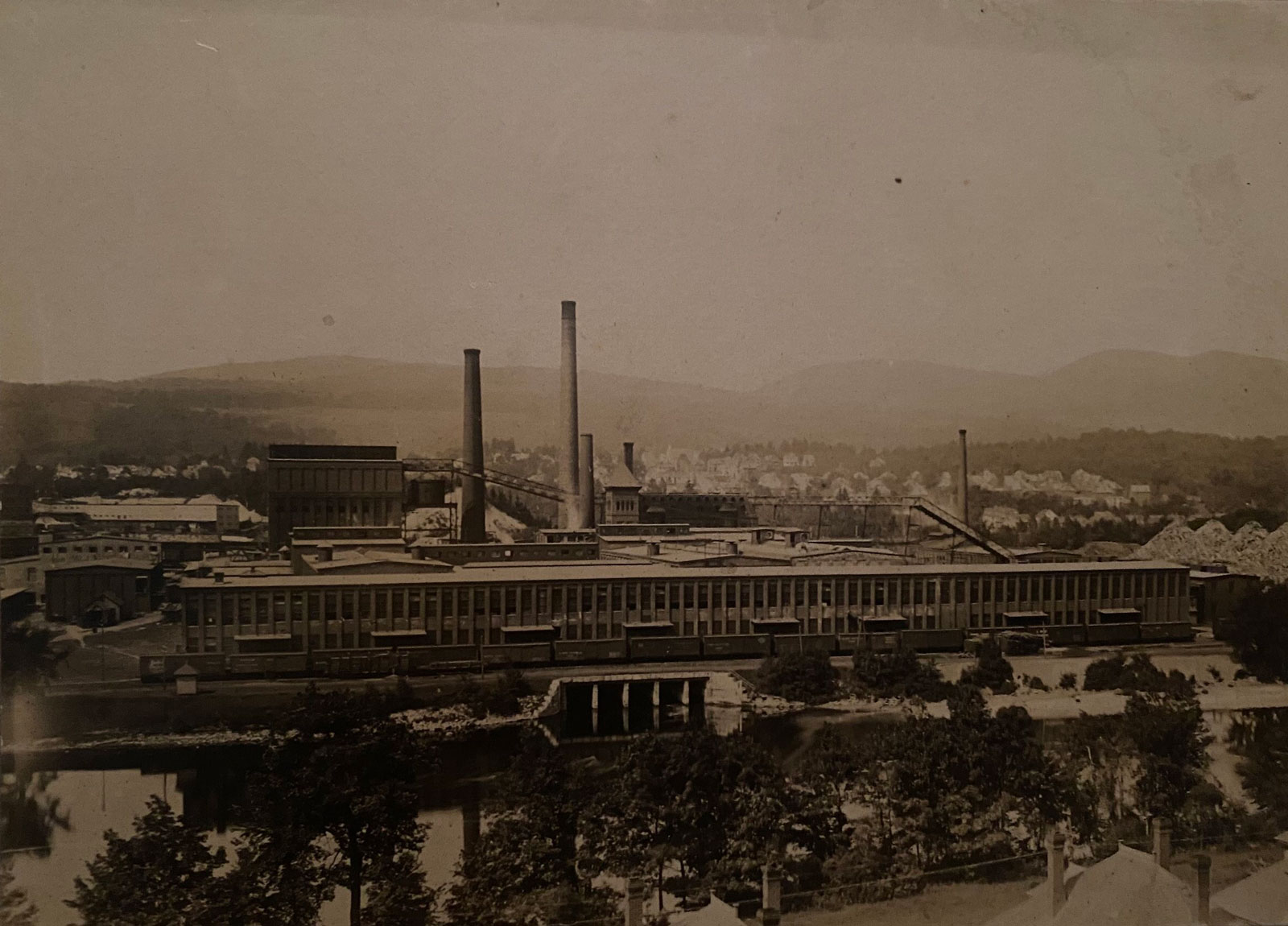

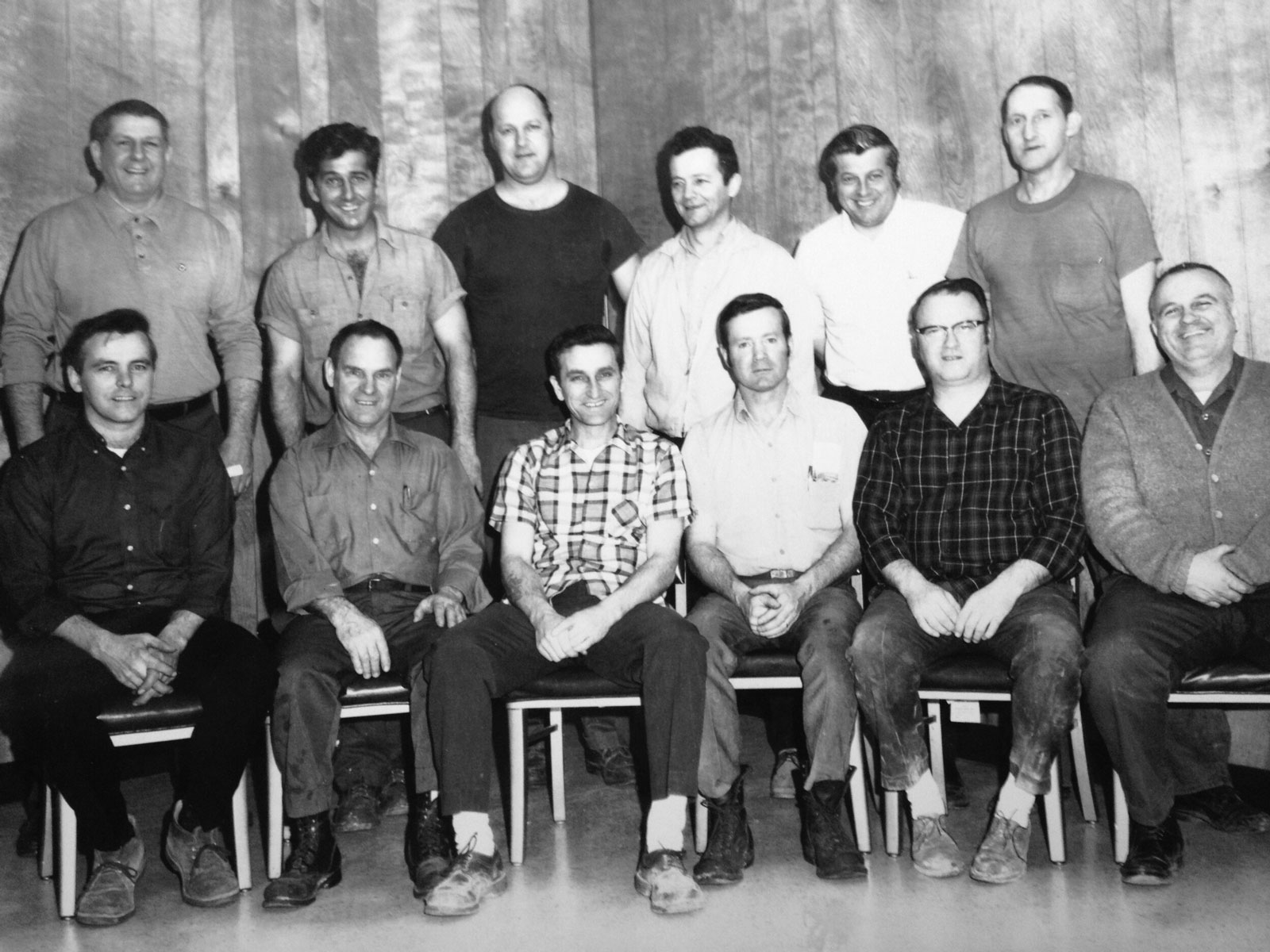

Hers was a you-can-always-do-more work ethic, and it was an extension of my parents’: my father worked as a pipe fitter in the local paper mill for over forty years without complaint. When Maine’s economy suffered from the oil crisis in the Seventies, and my father’s wages stalled, my mother picked apples, did piecework for Bass shoes, and worked as a school secretary to supplement their income. Hard work pays off, they always said, encouraging us to succeed beyond the circumference of our town. The cash in the pocket of my Jordache jeans proved it. And, as far as I knew, hard work was the only way up and out of working at the mill, where my parents, my grandparents, and my great-grandparents had all worked. There was no other ladder for me to climb.

In high school, I shoveled snow, delivered newspapers, waited tables, babysat, scooped ice cream. I worked through college to pay my tuition and rent, making pizza and donuts, bussing tables, operating a chairlift, delivering newspapers, waitressing again, nannying. I worked with Teresa for nine years, even while I worked those other jobs. And I had a lot of jobs. At last count, eighty-six.

Advertisement

*

Substitute teacher, Mexico and Rumford school districts, Maine

Dishwasher, Beloit College, Beloit, Wisconsin

Indoor soccer referee, Beloit College, Beloit, Wisconsin

ID checker, Beloit College Sports Center, Beloit, Wisconsin

English tutor for ESL student, Beloit College, Beloit, Wisconsin

Waitress, Federal Jack’s, Kennebunk, Maine

Deli worker, Kennebunk, Maine

Busperson, Scarborough Downs, Scarborough, Maine

Nanny for four children, Prouts Neck, Maine

Nanny for two children, Prouts Neck, Maine

Gardener at nursery, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Camp counselor, Camp Menominee, Eagle River, Wisconsin

Door-to-door nonprofit campaigner, Madison, Wisconsin

High school physical education teacher, Rumford, Maine

High school health teacher, Rumford, Maine

Junior high soccer coach, Mexico, Maine

Cable splicer, Sunday River ski resort, Newry, Maine

Waitress, Mother’s Restaurant, Bethel, Maine

Golf course groundskeeper, Bethel Inn and Country Club, Bethel, Maine

Softball umpire, Rumford, Maine

Mailroom operator, Sunday River ski resort, Newry, Maine

Daycare provider, Sunday River ski resort, Newry, Maine

Lift operator, Sunday River ski resort, Newry, Maine

Ski and snowboard instructor, Sunday River ski resort, Newry, Maine

Representative, Mistral snowboards, USIA ski trade show, Las Vegas, NV

Designer and copywriter, Mahoosuc Land Trust, Bethel, Maine

Cook, Pat’s Pizza, Bethel, Maine

Waitress, The Suds Pub, Bethel, Maine

Waitress, Run of the Mill Tavern, Plymouth, Massachusetts

Graphic designer, typesetter, office manager, Grassroots Graphics, Norway, Maine

Short-order cook and waitress, Tut’s diner, North Waterford, Maine

Admissions assistant, Gould Academy, Bethel, Maine

Administrative assistant, Maine Educational Services, Portland, Maine

Customer service representative/quality control, Graphics Express, Portland, Maine

Project/traffic manager, Perry and Banks Marketing and Public Relations, Portland, Maine

Salesperson then shipping manager, Amaryllis Apparel, Portland, Maine

Waitress, Portland, Maine

Retail salesperson, Dunne Roman, Portland, Maine

Assistant to real estate broker, Coldwell Banker, Cape Elizabeth, Maine

Furniture refinisher, Falmouth, Maine

Antique dealer, Falmouth, Maine

Hard work provided our families with homes, indoor plumbing, higher education, and Jordache jeans. Nobody was bound to the “company store,” however, the debt we accrued was far more costly. While the paper mill gave our town life since 1901, it also generated tons of toxic waste and, arguably, brought death. Particulates clouded our skies. Sludge brooded in our soil. Plumes from effluent pipes greased the river that ran through our town. Dioxin, cadmium, benzene, lead, naphthalene, nitrous oxide, sulfur dioxide, arsenic, furans, trichlorobenzene, chloroform, asbestos, mercury, phthalates: these are some of the by-products of papermaking. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, lung cancer, prostate cancer, aplastic anemia, colon cancer, liver cancer, esophageal cancer, asbestosis, Ewing’s sarcoma, emphysema, cancer of the brain, cancer of the heart: these are some of the illnesses that appeared in our town. People got sick in curious clusters, across generations of families, and in higher than average numbers.

In the summer of 1986, I had a job lined up at Boise Cascade, our mill. We college kids coveted the cash we could earn, even if it meant shoveling wood pulp in a windowless pit for eight hours a day or working amid dangerous toxics we couldn’t see. This was the same summer my father’s union went on strike. The strike disoriented people like my father, who grew up respecting another man’s job. When neighbors and friends crossed the picket line, it was a step too far. So, instead of a mill job, I stood in food lines, yelled at scabs, and scrambled to find work somewhere else. I eventually got a job bussing tables at a horse racetrack in Scarborough, Maine, and hitchhiked back and forth to Mexico whenever I could.

Ronald Reagan’s firing of over 11,000 air traffic controllers set the stage for my father’s union’s demise. When the strike ended that fall, of the 1,200 union members, around forty were permanently replaced by scabs and about 850 returned to work under a union-unfriendly boss in a union-unfriendly country. The ropes that had belayed us—pensions, company loyalty, health care—were replaced by leaders like Reagan telling us the free market would balance itself out. The overarching treatise of the working class went from hard work pays off to a corporation’s only responsibility is to its shareholders. The only thing to trickle down was the understanding that we were on our own: every man or woman for him or herself. We were whiplashed by the stop-and-go decisions of the company that employed us and felt powerless against the federal laws that weakened us. As I considered the fallout from the strike and the pollutants hovering low over our lonesome town, I knew then that factory life was a life I didn’t want to lead.

After graduating from Beloit College in 1990 with a BA in creative writing, I tended plants at a nursery in Milwaukee and later became a summer camp counselor in northern Wisconsin, while sending out dozens of resumes to newspapers and magazines. I received only one response: a fellowship offer from Mother Jones. Their letter indicated I’d receive a small stipend, but it wasn’t enough money to pay a modest rent, so I tossed it in the trash. Alternatively, a full-time offer in Mexico where I could live with my parents awaited my response: teaching high school gym, a job my mother helped arrange. There was also an opening for a junior high soccer coach that same fall. With student loan interest amassing faster than I could write a check and a recession settling in like a winter that never ends, what choice did I have?

By Christmas, the teaching gig ended. I wedged together seasonal and part-time work to keep my student loans minimally paid and my feckless 1973 Saab on the road. I taught skiing, groomed golf courses, waited tables, and did whatever else anyone hired me to do. I had no health insurance, so when I had medical emergencies (a third-degree burn, a severe allergic reaction to anesthesia), I would throw myself at the altar of the emergency room and then throw the subsequent bills in the trash. While I hamstered away (graphic designer, administrative assistant), I maxed out my Discover card to keep my car on the road to work the job that paid to keep my car on the road.

Still, I took pride in what I did: making the best donuts on the 7 AM to 7 PM shift; ensuring each slice of pizza had an equal amount of ingredients; topping off my customers’ water or beer glasses; sweeping snow off the chairlift so skiers could enjoy a warm seat. I paid to have the Saab hauled away, and instead hitched or biked wherever I needed to go. A spinal injury from skiing forced me to stop teaching, so I waited tables again to make rent. My parents gave me their beat-up K-car, which I sold for a few hundred dollars to a line cook so I could buy pots and pans and pay off the Discover card.

The Berlin Wall was dismantled, and we were told democracy had triumphed all around. In Mexico, however, opportunities were disappearing faster than that damn wall coming down. Our movie theater? Gone. Clothing stores? Gone. Churches? Gone. Restaurants? Gone. A place to buy a bicycle, underwear, a wedding ring? Gone, gone, gone.

As pundits and thinkers shouted about the end of history and the nation-state, I couldn’t seem to pull myself up out of the manhole of debt. As a first-generation college student, I didn’t know how to procure, as my mother called it, a “real job.” I applied to every real job I found, but there weren’t many, and I lacked advice. I deferred my student loans, which made the interest accrue to a level I’d likely still be paying off until I was fifty-four.

Finally, I got a real job, but was fired because a supervisor expected me to act differently than the men doing the same work. My mother insisted I file a sex discrimination suit, so I spent the little I had saved on hiring a lawyer to protect my reputation from going bad before the lawsuit began. The dispute ended in an arbitration in which both sides ceded our complaints. In sympathy, my parents sheltered me until I could figure out the next steps to take.

After forty-three years in the mill, with wages stagnant and union protections eroded, my father finally retired. Megastores moved into our working-class town. Rightly so. We needed their aggressively low prices and their full-time jobs and benefits to employ our mothers, who had been laid off from their jobs. Small businesses limped away with the gazebos, bandstands, and other happy diversions.

I didn’t blame anyone for my own flatlined career path; instead, I optimistically stored each job in my experience vault. But as I headed into my late twenties, around 1995, my CV was Swiss cheese. It was a CV potential employers didn’t embrace. I was making about $12,000 a year working three jobs (waitressing, project management, retail sales) when I was audited by the IRS over an apparent discrepancy: I had reported the correct amount of my waitressing earnings, but the restaurant had overreported my income. My choice boiled down to paying $3,000 in fines or hiring a lawyer to prove the IRS was wrong, which would have cost even more. I coughed up the cash and stole food from the restaurant that threw me under the bus.

I had bought into our country’s social contract—that if you adopted a can-do attitude and paid your dues, success would follow. I wondered, as I forked over a third of my income that year to the IRS, if there was something in the small print I had overlooked.

*

Paralegal, Bowman and Brooke LLP, Richmond, Virginia

Writer, The William and Mary News, Williamsburg, Virginia

Silver jewelry polisher, Charlottesville, Virginia

Project manager, Design Masters Associates, Toano, Virginia

Freelance proofreader and copy editor, Malmö, Sweden

Copywriter/website designer, Specialisterne software company, Copenhagen, Denmark

Home decor consultant, Malmö, Sweden

English tutor, Malmö, Sweden

Volunteer online editor/Indonesian translation coordinator, Kiva.org, Malmö, Sweden

Contributing and assistant managing editor, South of Sweden Magazine, Malmö, Sweden

Waitress for private caterer, Malmö, Sweden

Journalist and photographer, Palestinian Occupied Territories

Retail salesperson, Anthropologie, Berkeley, California (two days)

Women’s clothing store manager and buyer, Iniam, Oakland, California

Copywriter, Aligned Investments real estate development company, Oakland, California

Copywriter, Green Market Lane slow food marketplace, Oakland, California

Copywriter, Rockridge District Association and Oakland Events, Oakland, California

Subtitles manager and editor, Psychotherapy.net, San Francisco, California

Volunteer writing tutor, 826 Valencia writing center, San Francisco, California

Online content supervisor and editor, Narrative Magazine, San Francisco, California

Copywriter, Special Olympics, Washington, D.C.

Volunteer reader, The Paris Review, New York City

Communications coordinator, Mohawk Mountain ski race team, Cornwall, Connecticut

Copywriter, AMEICO, New Milford, Connecticut

Volunteer indexer, Familysearch.org, online

Gardener, Roxbury, Connecticut

In February 2001, when I was thirty-four and still living in Maine, my then boyfriend—a US Coast Guard officer—received orders to transfer to Virginia. He wanted me to come along. By April, we were engaged; in May, we married; come July, we were living in Virginia. He quickly paid off the last of my student loans, giving me a financial freedom I wanted but felt I hadn’t earned. I continued to work (paralegal, project manager, home decorator, copywriter, tutor, retail sales), but my husband secured our lives with his steady salary, access to good health care, and a military pension. My contribution to our financial wellbeing was to have no kids and do all the chores.

We were transferred to Sweden in 2005, then to San Francisco in 2007. By then, digital media had begun overtaking print; demand for coated magazine paper—the primary product of our mill—started to ebb, as did the livelihoods of the men and women who made it. In fact, manufacturing towns everywhere were dying alongside the industries that had once nourished them. The upward mobility of the working class corkscrewed shut. I took Arabic classes for a year at Berkeley, worked for a nonprofit (without pay), managed a boutique (without appreciation), and worked for an editor (who told me I’d never be a writer because I didn’t have the connections or the words).

When we moved to D.C. in 2012, I applied for about a hundred jobs and interviewed, successfully, for only one: writing copy for the Special Olympics. Days after making a generous offer, their office called to say they had made a mistake in hiring me, with no explanation. I spent weeks ghosting around free museums, running loops around the National Mall, and trying to figure out what to do. I was a middle-aged housewife with too many gaps in my CV. With no job prospects and a creative writing degree, I applied and got accepted to The New School’s MFA writing program, funded by my husband’s GI Bill.

My husband retired from the military in 2013, but he still needed to work and got a short-term position at the US Coast Guard Academy. With a VA loan, we bought an old house in a farm town in a quiet corner of Connecticut, where we could grow our own food, have a place to put all our stuff, and be within reach of The New School. While he drove to his job in New London that fall, I took the train to New York for classes. What was left of our savings, we spent on a new roof.

Throughout grad school, my multitasking continued (book critic, writer, editor, copywriter). When my husband’s job ended, we borrowed money from his parents and I worked as a gardener for under-the-table cash until he could find work. His pension paid the mortgage and my gardening kept us fed. Up to this point, we had moved every two or three years; bought and sold houses to great gain (2005) and great loss (2010). But, as it did for so many people, the global financial crisis of 2008 rubbed out the value our home had accrued. While the US government bailed out the banks that had caused the financial mess, the wealth gap kept widening.

Back in home in Maine, four out of five of children in our school district were food insecure; special education classes were overrun; and Rumford, the neighboring town to Mexico, boasted the highest crime rate in the state. The recession was just a grace note in the long-term plight of the working class, who had been living with a shitty economy and decreasing real estate prices for decades. The assault was almost indiscernible, like ice hardening over a culvert.

*

Copywriter, Lepere Analytics, Roxbury, Connecticut

Writing workshop teacher, Roxbury, Connecticut

Adjunct teacher, The Graduate Institute, Bethany, Connecticut

Freelance book critic, Oakland, California; Curaçao, Netherlands Antilles; Washington, D.C.; Roxbury, Connecticut

Contributing editor, Lit Hub, New York City

Contributing editor, Jewels of the North Atlantic, Iceland

Volunteer member of board of trustees, Minor Memorial Library, Roxbury, Connecticut

Visiting lecturer, Marymount Manhattan College, New York City

Book review editor (part-time), Orion Magazine, Northampton, Massachusetts

Mentor, PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship, New York City

Politicians are now trying to resell the idea of the American Dream to a workforce that has had its hand forced one too many times. But even when it seemed pretty good in our town, it was never so great, so there’s nothing to make great again. As the 1986 mill strike taught me, those simple rules of work hard, don’t be late, you earn what you deserve mean little today, if they ever meant anything at all. It turns out our dreams were filled with booby traps, ladders with busted rungs, and required money to achieve.

My struggles were small compared to those of my grandfather and my father. While I couldn’t pull myself out of the clogged sink trap of minimum wages until I married the right man, they had no choice but to accept the bargain of being steadily poisoned by the industry that sustained them. If it wasn’t for my father’s hard work, I may also have faced an untimely death myself. He gave me more than I could ever earn. Yet the arc of my employment history mirrors theirs. We saw the landscape shift beneath our feet while we could only stand still.

Mill Town: Reckoning with What Remains, by Kerri Arsenault, is published by St. Martin’s Press.