When I was first introduced to Stanley Crouch, more than twenty years ago, I never imagined becoming friends with him. Stanley, who died last week, at seventy-four, after a long illness, was at the height of his fame: a regular on the Charlie Rose show, a consultant to Ken Burns’s documentary on jazz, a consigliere to the trumpeter Wynton Marsalis for the concert series Jazz at Lincoln Center. I was a freelance jazz critic hardly five years out of college. To me, Stanley was the embodiment of a doctrinaire, traditionalist jazz establishment that was hostile to the avant-garde musicians I admired—many of whom he himself had once championed. Our meeting—arranged by my girlfriend at the time, who was friends with Stanley—didn’t look promising.

But Stanley liked sparring with antagonists. He lived for music and argument, and they went hand in hand. His passion for “the music” (as we in jazz call it) was contagious; so was the passion with which he defended his positions about what he called the “jazz fundamentals,” blues and swing. Whether you agreed with him or not, you had—to use one of his favorite verbs—to “deal” with him. And while Stanley didn’t hesitate to press his case with me, singing the praises of some new “young lion” in Marsalis’s orbit, or belittling Cecil Taylor, one of my heroes, he didn’t try to proselytize. Instead, he told stories about musicians, often about their lives, most of them unpublishable. “You see, Billy Higgins used to tell me,” he’d begin, as if he were sharing this confidence for the first time. He wasn’t; but then he’d be off and you’d have been a fool not to listen. Stanley traded on these stories throughout his career, but they gave his criticism, for all its rhetorical bombast, its allure of authenticity (another word he loved).

Many jazz critics avoid hanging out with musicians, usually because they’re afraid of jeopardizing their objectivity. Stanley was different. Not only did he think that spending time with musicians was crucial to understanding their work, he loved being around them. His appetite for the jazz life—for life, generally—seemed to know no limits. Some musicians thought he was full of shit, but even those who did mostly liked him. (Not all, of course: “Fuck him,” one musician he’d attacked wrote me just after his death.) Stanley knew jazz as intimately as he did because he lived the jazz life. If it led him to be less than objective, he didn’t see the point of being critically detached about the music he loved.

For a young writer who knew jazz mostly from records, this was mighty seductive. I’m sure Stanley knew this; he was good at sizing people up. He also knew that when it came to “how things really went down” in New York City, I knew precisely nothing. The nickname he chose for me was telling: Baby Shatz. He didn’t ask me to kiss his ring, but he found ways to remind me that I was in his city, and he had the keys. I didn’t care; I just wanted to listen to his tales. Stanley was not the most disciplined of writers, but he was one of America’s great raconteurs: at once urbane and down-home, witty, cutting, always impassioned. He’d started out in theater and remained an improvising artist. He had an unforgettable voice, a low, somewhat nasally instrument that could move into a higher register, with a slightly Southern twang common to many black people from Los Angeles of his generation.

In his preface to the 1995 Penguin edition of Saul Bellow’s novel Mr. Sammler’s Planet—one of his finest pieces of criticism—Stanley wrote of “Bellow’s gift for bringing together the intellect, the passion, the spirit, and the flesh.” Stanley had that gift, too, in his best writing. It’s no wonder both Bellow and Philip Roth befriended him. In his reverence for books and art, his loathing of academic cant, and his love of intellectual combat, Stanley was one of the last old-school New York intellectuals. Stanley in no way modeled himself on the New York intellectuals, but he had a lifelong fascination with Jews, “a people,” he wrote in his Bellow preface, “who cut their teeth on their endless variety of argument, high and low, the constant disruption of warring interpretations.” The New York intellectual he resembled most was the art critic Clement Greenberg, who, like Stanley, denounced kitsch with near-religious fervor and became an adviser to the painters he admired. Stanley’s alliance with Wynton Marsalis was not unlike Greenberg’s with Jackson Pollock, a partnership that fused critical advocacy and worldly self-interest. But his brazen style was closer to Norman Mailer, and, like Mailer, he won a pass to say outrageous things because—as my girlfriend at the time used to say, eyes rolled—“Stanley’s just being Stanley.”

Advertisement

In the 1980s, Stanley acquired a reputation as a black conservative because of his attacks on fellow black intellectuals and artists who trafficked, as he saw it, in victimology. But he was too unpredictable to pin down (and remained, throughout his life, a registered Democrat). If he felt the lure of the new black conservatism that flourished in Reaganite think tanks, he never fell for its assault on the welfare state—or its ideology of “color-blindness.” The reason he loathed gangsta rap and other black styles of radical will is that he believed they pandered to the racial fantasies of white audiences: a kind of latter-day minstrelsy. His wasn’t a “respectability” politics so much a politics of self-respect and black middle-class pride, white liberals be damned. And he didn’t hesitate to draw upon the cadences of black nationalism when it served him. In 2003, for example, he sparked a row in the jazz world when he published a piece accusing white critics of promoting inferior white musicians and “putting the white man in charge.”

What Stanley believed in, I think, was calling things as he saw them even if it meant speaking hard truths, which used to be the business of critics. He left a number of bruises, not always in the right places: his virulent review for The New Republic of Toni Morrison’s Beloved—“a blackface Holocaust novel”—was an especially unfortunate example of his weakness for gratuitous, attention-seeking polemic. Yet he remained faithful to his belief that a critic shouldn’t mince words or genuflect to fashionable pieties. And for all his criticisms of his black intellectual peers, he argued unceasingly that American culture and black culture are inseparable, indeed almost synonymous. America, he wrote, “is not so much a melting pot as it is a rich thick soup in which every ingredient both maintains its taste and also takes on the taste of everything else.” That, I think, is the thing Stanley most wanted to impart: what he considered the real taste of American culture. The idea that “anti-blackness” is foundational to the republic didn’t shock him, but neither did it preoccupy him; he was more interested in the miracle of how blackness transformed the nation’s culture—above all, in its music. Jazz, as he saw it, was not only the expression of American democracy, but it was also the only working model of meritocracy in America, other than sports. Rather than bemoan its absence in other arenas, he wanted to build on the example.

For Stanley, the person who best exemplified American culture’s possible grandeur was Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, whom he worshipped. Stanley had no chance of climbing to the top of Mount Ellington, even as he traded in his dashikis for suits. He wasn’t suave or elegant. He was a heavy-set, bald man from a working-class family whom no one would have described as handsome: a bruiser, not an aristocrat. (If there were ever a biopic, he’d be played by Ving Rhames, not Denzel Washington.) But Stanley was shrewd enough to turn his manner and looks into an asset. That a self-made man like him could become one of the country’s best-known cultural critics would become a source of rugged pride. But it was also proof of his convictions about the democratic nature and “rich mulatto tones” of American culture.

*

Stanley Crouch was born in 1945 in South-Central Los Angeles, and grew up listening to Duke Ellington thanks to his mother, a domestic worker who was a passionate jazz listener, and an equally passionate believer in her son’s education. His father, a heroin addict, didn’t enter his life until Stanley was twelve. (James Crouch shared a dealer with Charlie Parker: the wheelchair-bound Emry Byrd, whom Parker immortalized in his 1946 composition “Moose the Mooche.”) In his teens, Stanley writes in his 2006 collection of essays Considering Genius, “I discovered a truth that still applies: the Negro community, which has produced an extraordinary number of artists, has little or no value for art and will always, like most communities, drop to its knees before entertainment clichés or trends.” Jazz “offered an alternative to the mediocrity, oafishness, and stupidity that loomed over my adolescence.”

The struggle for civil rights offered a different kind of alternative to life in the ghetto. After the Watts uprising in LA in August 1965, Stanley briefly fell under the intoxicating spell of the black nationalism that, as he recalled, “swept through the younger generation like a hallucinatory fever of the intellect.” Waiting for the black revolution, he wrote insurrectionary poems heavily influenced by LeRoi Jones, who would soon rename himself Amiri Baraka. Jones was also a brilliant jazz critic, close to both John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, and Stanley, an amateur drummer, was deeply impressed by Jones’s argument that black music expressed an insurgent sensibility, the musical version of Black Power. By then a professor of drama and literature at the Claremont Colleges—he somehow talked his way into teaching gigs without ever finishing his studies at two community colleges—Stanley created the band Black Music Infinity with the alto saxophonist Arthur Blythe, the bassist Mark Dresser, and the tenor player David Murray, who was a student of his (all went on to illustrious careers in the avant-garde). He also performed in plays, notably a Studio Watts production of Jean Genet’s The Blacks. The Black Arts Movement in LA was on fire after Watts, and Stanley was at the heart of it.

Advertisement

But Stanley was also developing growing reservations about what he called the “tribal” impulse in the movement, and its deepening alienation from mainstream America, especially after he read Ralph Ellison’s 1964 essay collection Shadow and Act—a gift from the poet Jayne Cortez, Coleman’s ex-wife. What Stanley learned from Ellison was that black people didn’t need to separate from America or establish a black nation, because America was already permanently imprinted by their presence: if anyone had a claim to authentic Americanness, it was the black people who had built the country and created its most original art form, jazz. Later, he read Ellison’s 1969 essay on Ellington, in which he describes Duke’s “aura of mockery,” a “creative mockery” that “rises above itself to offer us something better, more creative and hopeful, than we’ve attained while seeking other standards.” Ellington’s secret was that he knew himself to be superior to those who looked down upon him as a mere entertainer, and who denied him the Pulitzer Prize.

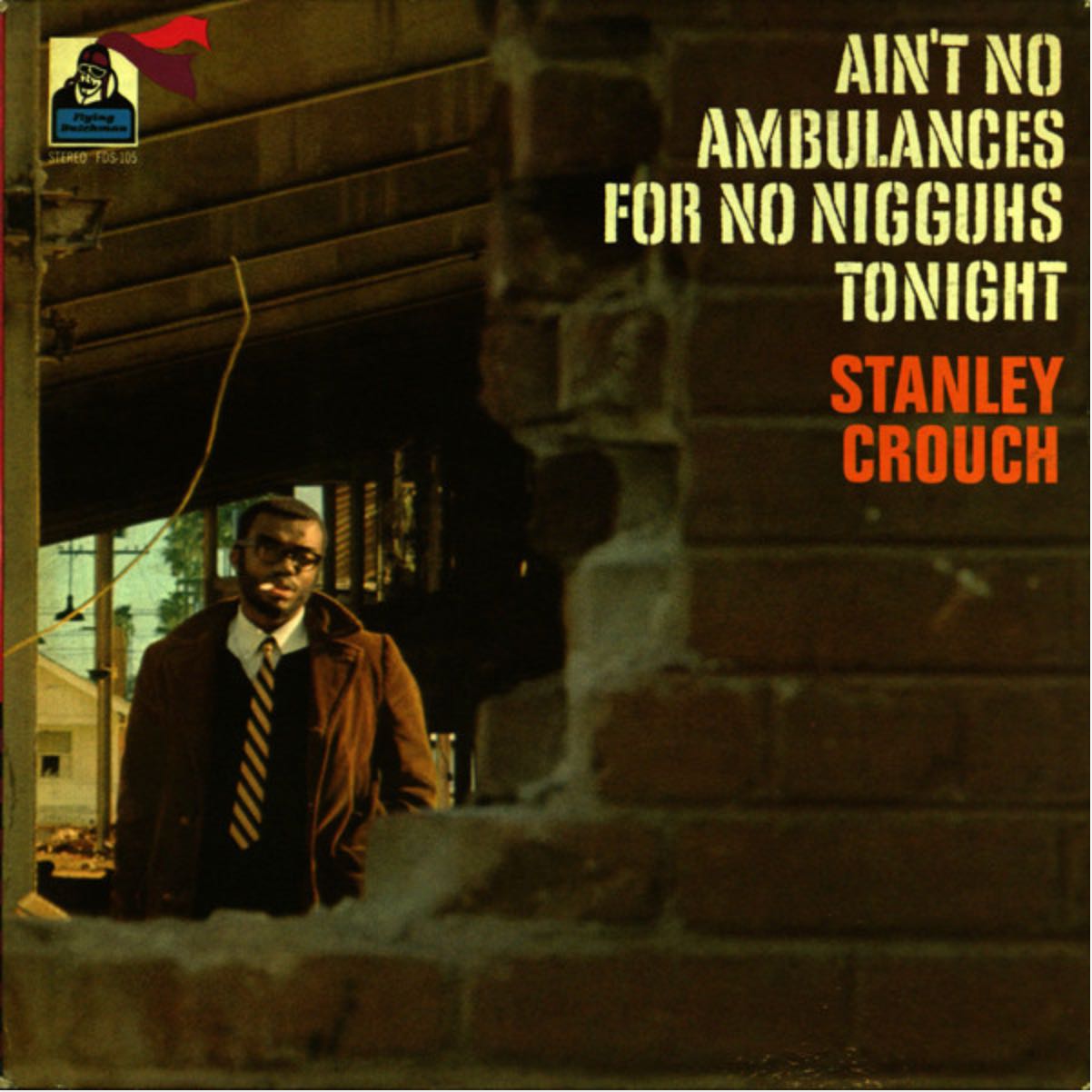

Stanley wasn’t quite ready to break with Baraka and the Black Arts Movement’s spirit of revolt, but he found himself increasingly swayed by Ellison’s celebration of the grace, poise, and sophistication of black culture, its supreme self-confidence and subtle—to white ears, all but inaudible—ridicule of the white world’s hypocrisies. You can hear the struggle between these two poles in Stanley’s 1969 live album Ain’t No Ambulances for No Nigguhs Tonight (the title is lifted from a remark made by someone during the Watts revolt, and was also used for Stanley’s 1972 volume of the album’s lyrics). A typical work of Black Arts poetry and speechifying in the mode of Gil Scott-Heron’s 1970 debut Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, its language owes everything to Baraka and Eldridge Cleaver, especially the homophobic slurs against “faggots” and “sissies” (identified as white). But Stanley also relishes lambasting “fraudulent, pseudo revolutionaries” and “fashion-plate nationalists… too busy selling clothes to notice they died in their bright African colors, Swahili colors dripping from their mouths.” He can’t quite muster Baraka’s sternness or his ideological discipline; he’s a revolutionary jester more than a political revolutionary. “I get everybody in this, see, so I may have to leave after I finish this one, if you can get to that.”

Stanley’s monologues on the album, moreover, are Ellisonian (and Ellingtonian) in their almost pedagogical insistence on the pervasive, albeit suppressed, influence, of black culture in America:

What I’m trying to say is that black people know more about white people and imitation black people and imitation black artists than they know about black artists…. We have not only had our greatest artists hidden from us, but the white man has thrown imitators of those artists at us and we know them better than the ones that did the first thing…. In American culture, what has been considered innovational has usually been whatever some white person has been able to get his hands on that some black person had already done…. If you subtract black people from America, you come up with the same corny thing that those people who got here in 1620 came up with, which was nothing, but a whole bunch of thieves if you ask the Indians because there ain’t no Iroquois left.

Once “you start studying your own music,” he continues, “you’ll find out who Louis [Armstrong] really is. He ain’t that grinnin’ coon you see on television for ten minutes every three or four months.” It’s time, he says, for “people like Ralph Ellison” to “write our own history books.” Stanley’s language would evolve, but he never veered from his belief that American mass culture prevented black Americans from discovering the true culture they had created—and what the white mainstream owed to them.

In 1975, Stanley moved to New York, where he shared a loft with David Murray, on Second Street and the Bowery. He traveled uptown to meet Ellison himself, and the critic Albert Murray, and later described those encounters as “a Southern and Southwestern one-two punch that flattened all of my former involvements with black nationalism and liberated me from the influence of LeRoi Jones, whose work I once copied as assiduously as Sonny Stitt did Charlie Parker’s.” Murray’s 1976 ode to black music, Stomping the Blues, would become Stanley’s bible, and he spread its gospel with missionary zeal.

In his early years in New York, Stanley booked concerts at the Tin Palace and ingratiated himself with some of New York’s best musicians, including Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. He was as close to the music as a critic can get without becoming a musician. But Stanley still played occasionally, and hadn’t given up on his dream of making it as a drummer. When the drumming chair in Cecil Taylor’s unit opened up, in the late 1970s, Stanley reportedly hoped that Taylor might hire him and give him a shot at glory. But Taylor declined to even audition him. Stanley, who reportedly never recovered from this slight, stopped playing drums, though he often insisted that if he’d only had proper training, he would have been one of the greats.

Stanley’s failure as a musician—and his rejection by Taylor—is sometimes offered as an explanation for his embittered turn against the jazz avant-garde, and his cruel outing of Taylor in SoHo Weekly News in 1982. His treatment of Taylor, and the vehemence with which he criticized Taylor’s work, was certainly striking, even peculiar, given his earlier admiration and their former friendship. (According to a pianist I know, Taylor was so wounded that he wanted to see Crouch “offed.”) But Stanley believed a critic had a right to change his mind.

By then, he had become enthralled by another avant-garde pianist whose work he preferred to Taylor’s. Don Pullen was a blazingly talented musician who admired Taylor and started out by emulating him, but Pullen’s mature style was all his own, and it had a much more traditional sense of swing and song form. Stanley wrote superb liner notes for Pullen, while missing no opportunity to praise Pullen against Taylor. Unlike “more publicized piano players” who “sacrificed the identifiable elements of jazz in favor of vocabularies that became progressively European in sound and substance,” Stanley wrote, “Pullen…managed to subvert his clusters and dissonant glissandi with such success that they were made to swing, fit inside song structures, and expand upon the harmonic options basic to the proposition of the blue note.” Pullen, in other words, was still a blues-and-swing man, who respected the fundamentals rather than trying to question or expand them.

When, years later, I asked Stanley why he’d become disenchanted with Taylor, he told me that once he’d listened to Olivier Messiaen’s piano compositions, Taylor’s struck him as an impoverished copy. Maybe, but I don’t hear much Messiaen in Taylor. I suspect, rather, that Stanley simply grew bored with the avant-garde and tired of its defiantly “outsider” stance, much as he’d turned away from the Black Arts Movement. Ellington hadn’t been an outsider, and Stanley didn’t want to be one, either. As he came into his own as a writer in the 1980s, a larger world opened up to him; so did greater opportunities than the loft jazz scene could ever supply. He coproduced one of the great albums of the decade, Joe Henderson’s State of the Tenor (1986), published artful liner notes for dozens of other musicians, and established himself as a contrarian essayist as zesty as Robert Hughes or James Wolcott.

Sometimes he was merely settling scores, usually with black nationalists, in prose still infected with the spirit of the movement he’d abandoned. (In this, he was reminiscent of certain New York intellectuals who’d started out as Marxists at City College only to become equally dogmatic neoconservatives.) But the aim of his criticism, aside from provocation, was to clear the ground for a more supple and elastic understanding of what he’d later call the “all-American skin game,” the strange tangle of race, identity, and power in American life. (If only he were around to write about Jessica “La Bombera” Krug, the white academic historian who “passed” as a black Latina until she outed herself in a recent blog post.) Black nationalism’s strident rhetoric thinly veiled its insecurity, he believed. A people who’d produced Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, and John Coltrane could afford to be more confident about their identity. They didn’t need dashikis or Kwanzaa to discover it.

During his 1980–1988 tenure at The Village Voice, Stanley expanded his palette as a writer, publishing elegant travel essays from Italy, a deeply felt portrait of the black figurative painter Bob Thompson, and an admiring profile of the gay novelist John Rechy—his homophobia having mutated into warm sympathy, and an almost voyeuristic fascination. He even wrote about R&B when a talent that couldn’t be denied overcame his reflexive suspicion of popular culture. One of his loveliest pieces was a short essay on Marvin Gaye, whom he compared to Ellington and Miles Davis. The “intricacy and subtlety” of Gaye’s work, he wrote, “challenge the adolescent sentimentality at the core of the idiom without abandoning the dance and seductive inclinations of the tradition.” Stanley also heard “a spiritual anguish” in his singing, “a mosquito net of sorrow the sleeping Don Juan would have to meet upon awakening.” Some of these essays were reprinted in his 1991 collection Notes of a Hanging Judge, his finest book.

Having made it in a white-dominated publishing world, Stanley regarded other black writers warily. He sneered at one young black writer at the Voice—now one of America’s more prominent essayists—that he was there only because of affirmative action. In 1988, a young black music critic at the Voice baited Stanley by saying Public Enemy was as good as Coltrane. Stanley punched him in the face, knocking him to the floor—and, by so doing, lost his job. But he no longer needed the Voice, since he had forged an alliance with the musician who would help him to move from downtown celebrity to midtown power broker. When Stanley first saw Wynton Marsalis perform, with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in 1980, Marsalis was a nineteen-year-old-student at Juilliard. He had flawless technique and an impeccable origin story, coming from a distinguished musical family in jazz’s birthplace, New Orleans. They had dinner shortly thereafter, and Stanley played him Ornette Coleman’s “Bird Food.” “I never heard Charlie Parker play like that,” Marsalis responded. Stanley began to mentor him, introducing him to Ellison and Murray. Seven years later, they launched Jazz at Lincoln Center.

*

Jazz at Lincoln Center (JALC) was a formidable achievement: a veritable palace devoted to the performance and celebration of jazz in the middle of Manhattan, on par with the Metropolitan Opera. For the first decade or so of its existence, JALC was almost Thermidorean in its insistence upon the fundamentals of blues and swing and its aversion to avant-garde forms of expression. As the jazz historian John Gennari has observed, Stanley presided over “a kind of new moldy-fig classicism,” an allusion to white critics in the 1940s who promoted swing against the innovations of the black-led bebop movement. The difference was that Stanley’s stance had a strong element of black self-assertion and cultural reclamation—and there were plenty of young black musicians, the so-called Young Lions, who felt the same way. Jazz, he argued, echoing Ellison and Murray, was too proud, too serious, and too venerable a discipline to be described as a music of eternal racial protest: “Having the worst luck with white people, women, gambling, or keeping a job is no guarantee that a Negro will be able to swing the blues as well as, for instance, Stan Getz, a pure and gifted musician from any perspective.” (Stanley savored the word “Negro,” using it alternately as an honorific and a putdown.) Black people hadn’t created jazz, or mastered the form, because they’d suffered, or because of some native genius, but because they’d patiently developed a tradition and worked hard at preserving and extending it. And these were the goals of his project with Marsalis.

When JALC came under criticism for the narrowness of its vision, Stanley didn’t hesitate to take out the rhetorical knives he’d sharpened as a disciple of Baraka. He described the trumpeter Dave Douglas as “white, blond, short, and from the upper middle class,” and said his music “provides the same thing that at a certain point so-called ‘West Coast Jazz’ provided, which is a rebellion against the Negro”—an argument that he might have lifted from the chapter on “cool jazz” in Baraka’s 1963 study Blues People. (It should be noted that Stanley had no problem with white musicians—he loved the tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano, for example—so long as they played in what he considered to be the blues tradition.)

The fullest expression of Stanley’s work as an ideologue was not an essay or interview, or even the 2001 Ken Burns documentary Jazz, which introduced Stanley’s views to the wider public. It was a sermon he wrote for Marsalis’s 1989 album The Majesty of the Blues, “Premature Autopsies.” (The title may have been a knowing allusion to the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s 1968 piece “Jazz Death?”) The sermon was recited on the album by the Reverend Jeremiah Wright Jr.—yes, that Jeremiah Wright, the fiery preacher whose church Barack Obama attended in Chicago, and whose bleak vision of American racism the then candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination condemned during his 2008 campaign. As Marsalis’s band plays a New Orleans dirge, Wright excoriates the “moneylenders of the marketplace,” who “have never ever known the difference between the place where bodies were sold and the place where souls were saved,” and who gleefully celebrated the death of jazz, that “noble sound” that provided “the level of revelation we can only expect of great art.”

Stanley seemed to have seen the light and anointed himself the designated mourner and resurrectionist, if not the messiah, of the jazz tradition. Innovation, whether it involved borrowing from European concert music or black popular music like hip hop, wasn’t just deviation. It was sin.

This was a strange position for so secular a critic, and for a writer so inclined to doubt and contention. In a searing review of Miles Davis’s autobiography, published in 1990 in The New Republic, Stanley wrote that Davis’s embrace of electric instruments reflected “the essential failure of contemporary Negro culture: its mock-democratic idea that the elite, too, should like it down in the gutter.” Miles, he added, “blurts a sound so decadent that it can no longer disguise the shriveling of its maker’s soul.” Having banished Miles from the kingdom of jazz, Stanley spent the first half of the 1990s fiercely proselytizing for Marsalis’s jazz revivalism, in what Gennari rightly calls a “macho gangster pose,” and castigating musicians who strayed from the righteous path. When the critic K. Leander Williams panned Marsalis’s Pulitzer Prize–winning 1997 composition about slavery, Blood on the Fields, Stanley threatened to clean his ears out with steel wool. “What are you doing here,” he asked a well-known free jazz pianist at a funeral. “I thought this event was for VIPs.”

By the time I became friends with Stanley, a few years later, he’d settled into a less bellicose mood, at least off the page. (His Daily News column, which I ignored, was often embarrassingly reactionary.) After one of our first dinners together in the West Village, we went to his apartment to listen to music. He put on an album by a young pianist, a Marsalis disciple I respected but didn’t find all that exciting. Then he put on Sonny Meets Hawk!, Sonny Rollins’s 1963 album with Coleman Hawkins. As the pianist Paul Bley took a solo on “Yesterdays,” he whispered, “Now, see, this is what the avant-garde cats should be listening to.” Stanley loved Bley, for the same reason he loved Don Pullen: unlike Cecil Taylor, Bley had discovered a way to play free while honoring the fundamentals. Stanley’s lecture didn’t dampen my enthusiasm for Taylor. But he was so eloquent about what he loved that he (almost) made you forget his tirades against what he didn’t.

He spent the rest of the evening talking up his forthcoming novel, Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome, which he expected to be a major event in American fiction and to catapult him into the ranks of Bellow, Ellison, and Roth. (To my knowledge, Stanley didn’t read women novelists.) It was not to be. The novel, about a love affair between a white woman and a black saxophonist, was a critical catastrophe, memorable largely for the demolitions it inspired by John Updike in The New Yorker and Dale Peck in The New Republic. When Stanley subsequently saw Peck sitting in the same restaurant, he walked over to his table and smacked him.

Stanley stood by his book, but he put its failure to good use: for the first time, notes of humility began to appear in his writing. In his 2004 essay on Ellington’s symphonic “tone parallel” to black American history, Black, Brown and Beige, mocked by Paul Bowles and other critics after its 1943 premiere, Stanley wrote movingly of Ellington’s bitter sense of disappointment, which led the composer and band leader never again to attempt a work on such a grand scale. Stanley also argued passionately in defense of Ellington’s once-maligned late suites, which are now widely seen as some of his finest work. But the moment in that essay I find most stirring is its sublime—and, for Stanley, surprisingly austere—description of Mahalia Jackson, who laid aside her resistance to profane music to sing in Ellington’s 1958 recording of the “black” section of Black, Brown and Beige:

Within her marvelous brown being, the entire heritage of the religious music from slavery and the spiritual music that came after bondage was given communicative residence of a special kind. She was a woman of large beauty and regal presence. Her voice was humbling because it was absolutely pure in its impersonality, which meant that it sounded unlike personal expression or autobiography or belief. She possessed the quality that all great religious singers must have—the ability to give the impression that they are not telling you what they believe or what happened to them somewhere in the world at some time, no, but what was always true in every time and in every place.

*

After moving to London in 2007, I lost touch with Stanley. When I saw him on a visit to New York in January 2010, we heard a set of stately, intelligent straight-ahead jazz by the late pianist Mulgrew Miller, at the Jazz Standard. “I went to that same club where we heard Mulgrew Miller and heard what amounts to a miracle of sorts,” he wrote me in May. The trumpeter Wallace Roney (one of the first among a number of jazz musicians to die of Covid-19) had played there with a new band, and Stanley told me, “I wished you were still in New York throughout the set because it would have been quite thrilling. All is well. It was a good omen, with the grand old man Hank Jones having passed away on Sunday at 91.” The next time I heard from Stanley, that August, he told me that he was just reemerging from a terrible depression, and “the feeling of being back in the world has brought many soaring sensations…. I do not believe in therapy, or do not believe it worth my time, but friends remain an invincible position in handling whatever I am faced with and what I must do to get from one place to the next. Thank you again, the fire has been relit under the brain pan.”

When I moved back to New York the next year, he took me to dinner to celebrate. He seemed rejuvenated. He was working furiously to finish the first volume of his long-awaited Charlie Parker biography, while still finding time to enjoy the city he loved so passionately. The exhibit of Picasso’s paintings of Marie-Thérèse Walter at the Gagosian gallery was, he told me, one of the best things he’d ever seen, and I must go. (I did; he was right.) “That was a pure New York talk of the kind I dreamed of before moving out here in 1975,” he emailed me the next morning. “Knowing the right people means the best versions can always happen. I sincerely hope that you find all of the actual happiness possible now that you have moved back home. It will also be good to see you with your child as you unavoidably play the proud father, which is never less than a vital identity—especially when one is not playing.”

Stanley had grown into a new vocation, that of mentor to younger writers. His supportiveness felt authentic, even if it contained the occasional undertone of one-upmanship. When, in 2013, I published an essay on Charles Mingus, he emailed me, “I had never expected to see you climb over that fence and reveal your coming mastery of emitting deeper meanings—profound, fraudulent, accidental and tragic-comic at the end—but it was done and will stand apart from you and everyone else, becoming a truth needing nothing but itself.” Curiously, that praise was followed by an attack on Amiri Baraka, who seemed still to haunt him, and a plug for his forthcoming book on Charlie Parker:

That boy LeRoi decided to descend lower than the icy place where Satan is frozen into an eternal “payback” for his sins of cowardice and “a taste for power,” as Elaine Brown so accurately called it in when describing her career as a black pantherette in the show business of saber rattling. Gone are the days. Kansas City Lightning will expand your ambitions substantially because you will read it very well, the task of all having truest ambition.

Kansas City Lightning, finally published in 2013, had been in the making since 1987. When he first applied for a fellowship to write the book, Ellison’s letter of support remarked that Stanley’s work displayed “an unintended pretentiousness; a temptation to place too much of a load of cultural, sociological, and historical analysis upon the slender reed of Parker’s saxophone as upon the brief and narrow social range of his turbulent life.” (Ellison famously disliked Parker’s work.) But Stanley wasn’t a scholar; nor was he an original thinker like Murray, whose ideas about the blues he popularized (and whose influence he would later, and unconvincingly, try to disavow). Stanley was a cultural mythmaker of rare inspiration. Kansas City Lightning wasn’t the most reliable account of Parker’s early life, but it was animated by extraordinarily candid interviews with musicians who’d known him, perfumed with Stanley’s deep knowledge of the jazz life, and written with greater restraint than usual. Parker remains something of a cipher, but Stanley memorably evoked the epic resonances of his journey from Kansas City to New York, where he changed the face of American music.

I reviewed the book for The New York Review and told Stanley in an email that I heard echoes of Ellison and Murray (who had died earlier that year) in his writing. “But that is no more than sauce,” he replied. “The meat on the bone is all mine. That also is how it goes. VIA, SC.” (He always signed his emails “VIA,” for “victory is assured.”) He doubted that “either Ellison or Murray would have been happy with my book because there are too many original ideas and insights, though they often build upon their work Perhaps neither of them felt as Charlie Parker did, ‘There is always room at the top.’” Unlike Ellison, who, in Stanley’s words, had “lived with a constant, debilitating sense of having failed” because he could never finish his follow-up to Invisible Man, he had completed his great book, or at least its first volume.

But while the reviews of Kansas City Lightning were mostly favorable, they were more respectful than ecstatic. And the hour of triumph was short-lived. In December 2014, Stanley’s beloved sister died. He had spoken to her two weeks earlier, and they had “traded a lot of laughs, going back over the funniest and most foolish and most enlightening memories—tears, laughter, and the most durable facets of experience…. I mulled over how well we had come to deal with each other on the higher side of sibling life, having both lived through the lower and darker side, where all the correct or incorrect anger resided…. Gone was all the trivia, whirling away in a sandstorm of memory. Victoria Maria Crouch, my only sister, is also gone, as vitally unique as any I have ever known.”

In the last few years of his life, Stanley was in almost constant poor health. The deterioration was not only physical. He’d been writing a novel, inspired by the “nighttown” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is set in a brothel. He sent me a few chapters, convinced it was a grand act of transgression:

The girl’s name in the sex business was Praline and her marketing motto was, “Never met a dick I couldn’t take.” She was what Negroes called “thick,” which made her ample calves, thighs, and backside virtues for a frame always accepted as superior to anyone considered far too thin, except for the rare one of virtuoso muscular control and apparently bottomless capacity who could command an anxiety swaddled in shock and awe.

It became much more graphic. I shouldn’t have been surprised: Stanley had often extolled the eroticism of jazz, the “boudoir” ambience that had nourished the music from its early days. Stanley explained that he’d just read the critic Andrew Graham-Dixon’s biography of Caravaggio and was struck by Graham-Dixon’s argument about “concealing a devout message within an apparently profane, secular subject.” That, Stanley said, “is a fundamental blues theme: the spiritual rising up from the muck and dripping filth as it licks itself clean.” The spiritual dimensions of Stanley’s novel eluded me, and I couldn’t see it being published in an environment shaped by increasing concerns over sexism. The problem wasn’t that it was vulgar; the problem was that it was dull. I replied as politely as I could, and Stanley, too proud to say that he was hurt, never brought it up again.

Sadder still, Stanley seemed out of touch with a jazz scene that combined an appreciation of his “fundamentals” with a growing curiosity about the 1960s and 1970s avant-garde he’d pilloried. (When I mentioned the pianist Craig Taborn, he grouchily acknowledged that “he can play.”) Much as I missed hearing from him, his retreat from public life struck me as a kind of mercy. He had become an anachronism.

I saw Stanley for the last time a year ago, at a nursing home in Riverdale, in the Bronx, where he had moved after a fall in his apartment. He was sitting quietly in his wheelchair in a common area when I arrived, unannounced, with the writer Clifford Thompson. When he saw us, Stanley smiled and said, “My day just got a lot better. Come, let’s go to my room.” (Cliff tried to thank him for his work, but Stanley wasn’t feeling sentimental: “Nobody owes anybody anything.”)

For the next twenty minutes, he delivered an obscene monologue about James Baldwin’s intimate life. It was a scene out of one of those Bellow novels that Stanley had written so brilliantly about. Cliff and I looked at each other in disbelief and sadness. Hoping to change the subject, I asked Stanley about his long friendship with Ornette Coleman. Suddenly, all of his lucidity came back, and he spoke with his usual salty lyricism and no-bullshit candor about the man from Texas who’d launched the free jazz revolution.

Don’t believe anything Ornette said about his theory of “harmolodics,” he told us, as if letting us in on the real deal. That was simply justificatory nonsense. Ornette, he said, was a country blues player of genius, not an intellectual. And did either of us know that Cecil Taylor used to go by Ornette’s place to practice in the early 1980s? Denardo, Ornette’s son, has tapes of what they played, which hardly anyone has heard—other than Stanley, of course.

I looked around the room. There were no records. He no longer needed them. They were all dancing in his head.