The Palestinian militant film project emerged in the aftermath of the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, hoping to win international sympathy and solidarity by showing Palestine as one dialect in a global language of anti-colonial struggle. The war—which lasted six days—ended in crushing defeat for the Arab armies and created a new, second wave of Palestinian refugees, as well as an occupation of the West Bank and Gaza that continues to this day. Soon after, Jordan became the main base of operations for the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), which had formed in 1964 and carried out attacks on Israel with passive support from the Hashemite Kingdom. During this time, the PLO, like other anti-colonial movements of the era, also turned to the arts to carry its message to a wider audience—developing a counterinformation program aimed at broadening the battlefield of the Palestinian resistance.

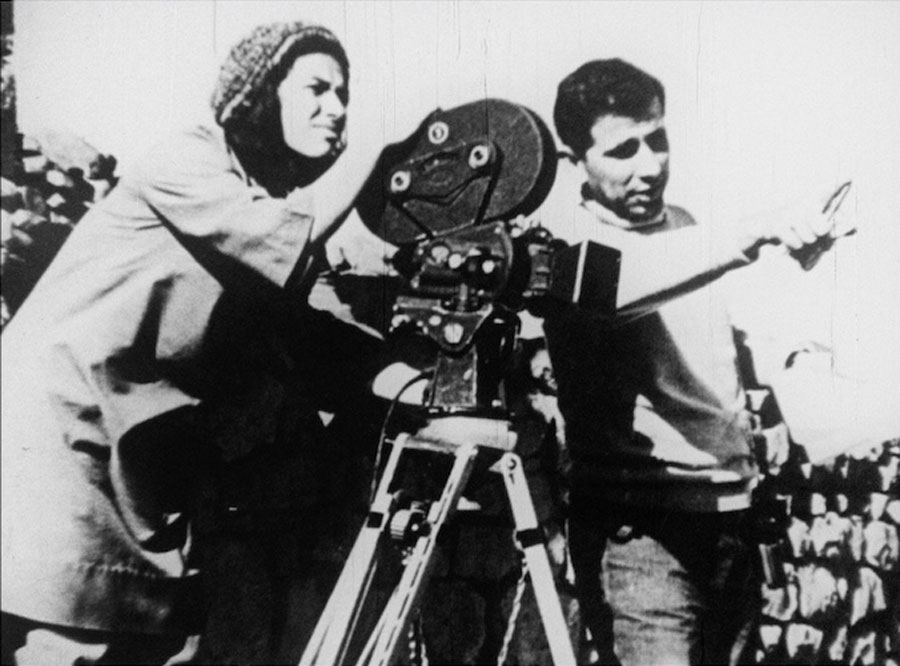

The Palestine Film Unit (PFU) emerged from this milieu. Founded in Jordan in 1968 by Mustafa Abu Ali, Hani Jawharieh, and Sulafa Jadallah—considered by some to be the first Arab camerawoman—the PFU produced many 16mm documentaries over the next fourteen years, which were among the earliest examples of a militant Palestinian cinema. The initial films highlighted material elements of Palestinian disenfranchisement and death, modeling the aesthetics of other anti-imperialist movements at the time, like those in Cuba, Vietnam, and Angola. PLO fighters were notably inspired by their Vietnamese comrades—the fedayeen, or guerrillas, in fact, traveled to Vietnam to learn resistance tactics from the Vietcong, some even taking noms de guerre such as Abu Khaled Hanoi.

Abu Ali, who studied film in London, was interested in what it would mean to make films closer to his own freedom struggle. The PFU’s goal was to document the daily lives of Palestinians engaged in acts of resistance, both large and small, and support the efforts of the fedayeen. The group worked with two cameras at first, developing their negatives in the kitchen of a PLO safe house in Amman, Jordan, drying the prints over the stovetops. The filmmakers developed a body of scenes, shot without a script or, sometimes, a clear purpose. But the intention was cooperative: footage drawn from this reservoir would later be edited together for a particular campaign. Many of these films therefore had striking visual similarities, as they were built from a common collection of visual images upon which the filmmakers could overlay more individual or personal perspectives using editing and voiceovers.

Most of the resulting films, such as Palestine Will Win (1969), were made for non-Palestinian audiences and, like that one—directed by Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan at the behest of General Union of Palestinian Students in France—were made by non-Palestinian directors with connections to the European student movements of the time. Another, Al-Fatah, Palestine (1970), directed by the Italian Luigi Perelli, gained currency with the Italian radical student movement, which printed promotional posters for the film.

The PFU films directed by Palestinians are mesmerizing. Jawherieh’s Training Camp, Jordan (1969) features collaged images of fedayeen in military training, their bodies writhing in dirt and sweat, Kalashnikovs held above the dust in preparation for a coming mission. Abu Ali’s They Do Not Exist (1974), perhaps the most famous film produced in this period, is haunting, its title lifted from a 1969 interview with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, who declared, “It was not as though there was a Palestinian people in Palestine…. They did not exist.” This foundational mythology—of “a land without a people for a people without a land”—is reflected in early Zionist filmmaking, which depicted kibbutzim as sites of heroism, their members tilling the soil, resisting Arab invaders, and building a Jewish state out of the Palestinian wilderness, in a style reminiscent of the American Western pioneer drama.

Abu Ali’s film offers a counternarrative by showing how Palestinian non-existence comes to be. They Do Not Exist opens with children eating ice cream, mothers watering plants—a casual morning in southern Lebanon’s Nabatieh refugee camp. A little girl in the camp is writing a letter to her “brother,” a fedayee fighting for Palestine, sending with it a gift—a towel and a piece of soap—though she wishes she could have offered him “something better.” The film ends with images of the camp flattened by Israeli shelling, and interviews with the parents of some of the murdered children. The fedayee, now seen holding the letter from his sister, looks off into the distance and reflects, “Better for this heart to beat…. What a waste of days without love and loving.” Then, an unceremonious cut to black: “This film was rescued from a 16mm copy, where the last minute was missing.”

Advertisement

Palestinian cinema has always been saddled with the psychic weight of colonization. The Israeli program of relentless settlement building is a process of destruction and construction that not only alters the physical appearance of Palestine, cleansing a land of its people, but also serves as a politicide, a means of delimiting the Palestinian imagination. Film offers liberatory possibilities, then: with the projection of moving images onto a screen, a people can imagine something different, something other.

Or this is one narrative, at least. More likely, the motivation for much of this audiovisual history was more practical. The PLO was engaged in an effort to reconstitute Palestinian life in exile, mobilizing refugees to work in a variety of industries in the camps, and employing its members in the production of cultural objects, like books and posters, with the goal of disseminating a vision of Palestinian life to the international community. The PLO worked with the French Communist Party and its networks in Paris to make copies of the films that could be sent to festivals around the world. Palestinian images came, as Egyptian academic Omnia El Shakry writes, to form “the limit zone between an ideological commitment to a decolonizing internationalism and the pragmatic realities of national liberation.”

As a result, the militant period was one in which Palestinian filmmakers worked in some cases with others to represent their own image. In 1970, Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin visited the Palestinian fedayeen in Jordan and outlined their plans to make a film about the Palestinian struggle. Godard had famously said that his “soul is Palestinian,” and that “the Palestinian struggle is just a part of the general struggle all over the world against imperialism, related to Vietnam, to Laos, to Cuba, to South America.” The duo’s hope was for the tentatively titled Until Victory/Palestine Will Win to become part of the oeuvre of the Dziga Vertov Group, the radical film experiment they’d founded two years earlier, which presented Marxist meditations on the politics of the 1960s and 1970s.

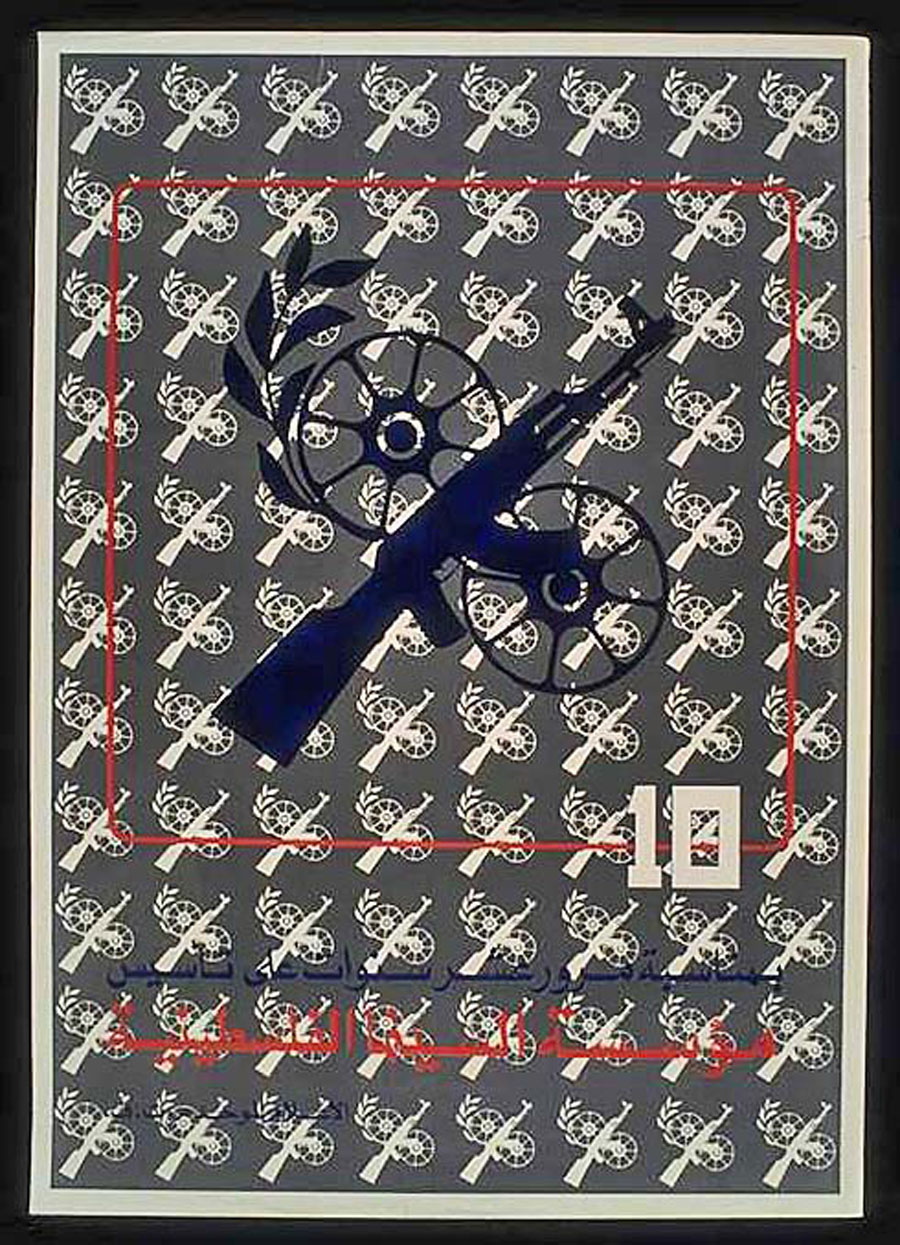

But within months of the French filmmakers’ visit, the PLO clashed with its hosts in Jordan. In the conflict that became known as Black September, the Jordanian army attempted to oust Palestinian leadership from the country. With its fighters driven out, the PLO moved its base of operations to Beirut, in Lebanon, and the PFU was renamed the Palestine Cinema Institute (PCI), becoming one of the several departments in a PLO Unified Media, which included photography, newspaper, radio, and film. In the bloodletting of Black September, many of the Godard–Gorin project’s protagonists were killed, and the filmmakers were forced to abandon it.

This is not to say they were unaffected by their journey. That same year, the pair traveled to New York to do fundraising, a trip chronicled in the film Godard in America (1970). In an interview with the film critic Andrew Sarris, Godard was asked: “Can the camera be an instrument of revolution, or do you need to pick up a bomb?” Godard prevaricated, unable or unwilling to give a definitive answer. Sarris pushed, “So do you consider yourself more a revolutionary or a filmmaker?” Quickly, this time, Godard replied, “I believe in working for the revolution through filmmaking.”

In 1982, the Israeli government used the chaos of the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) as a pretext to invade the country, occupying parts of Beirut and attempting to ferret out and force the PLO fighters from the city. In the course of this offensive, Israeli soldiers seized Palestinian films from the PLO’s Cultural Arts Section, many of which are today kept in the heavily secured Israel Defense Forces Archive. The PLO’s exile from its Lebanese stronghold signaled the end of the militant filmmaking work; without the ability to organize armed resistance to Israel from any contiguous country, the PLO was forced to change its tactics and ultimately opted to pursue a diplomatic, rather than a military strategy in its struggle for Palestinian self-determination. The magnitude of this loss is felt years later; the PFU’s first film—No to the Peaceful Solution (1969)—was never recovered.

According to academics Nadia Yaqub and Laura Marks, many of the films that did escape capture during the Beirut conflict had already been smuggled abroad. Five years before the Israeli invasion, fearing imminent war and spooked by the Phalangist looting of Studio Baalbek—then one of the most important movie studios in the Arab world—in 1975, Abu Ali shipped out hundreds of rushes of unedited film by boat from Sidon to Cyprus, and then by air to a production house run by the Italian Communist Party in Rome. Years later, Emily Jacir, a Palestinian filmmaker, and Monica Maurer, a German filmmaker who had worked with the PLO, got access to the archive and helped digitize the surviving reels of Tel al Zaatar (1977), a collaboration between Italian and Palestinian directors that documented the aftermath of the 1976 massacre of more than 2,000 Palestinians in the Tel al-Zaatar refugee camp. The terrifying images show Palestinians fleeing on trucks, mothers holding their children, a landscape of horror.

Advertisement

This search for a lost archive is a central trope of “post”-conflict cinema, though the end result is not often vindication. In Kings and Extras: Digging for a Palestinian Image (2004), the director Azza El Hassan participates in a hilarious and increasingly farcical romp through Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine in search of Palestinian film archives. They will, of course, elude her. One of the women El Hassan interviews turns to her and says, “Now is not the time to be thinking about cinema.”

Underneath all of this frantic searching, something more complex is buried. Clearly, Palestinian art is not wholly a reaction to its erasure. Nevertheless, if it is the case, as Palestinian academic Rashid Khalidi has argued, that the idea of a Palestinian identity was reignited after the trauma of 1967, then Palestinian art cannot be completely separated from Israel’s efforts to destroy it. In fact, the expectation of impermanence or ruin often colors the production of Palestinian art to begin with—like a cameraperson nearing end of their reel, Palestinian artists must work to make the most of the time they have. These attempts by Palestinians at recovery, then, are part of an effort to glean new meanings from loss.

In Godard’s 1976 film Here & Elsewhere, he reflects on the revolutionary projects of his earlier years. In one scene, he and codirector Anne-Marie Miéville show footage from the unfinished Until Victory of a Lebanese woman who announces to the camera that she is pregnant with a future Palestinian freedom fighter. Miéville then announces in a voiceover that the story was made up.

Fabrications like these were unexceptional in anti-colonial films; the Palestinian filmmakers of the period never intended theirs to be a cinema verité. But can these works even be said to be cinema? It would be easy to dismiss them as agitprop—but Palestinian filmmakers wouldn’t have thought this a bad word. “The best form of propaganda is armed struggle” reads an opening title card for the 1971 solidarity film Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War, directed by Japanese filmmakers Kōji Wakamatsu and Masao Adachi. The movie described itself as a “news film,” according to an officer in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP)—the secular, Marxist–Leninist organization that was then the second largest group in the PLO after Fatah—who adds, in one of the interviews that, “propaganda is in fact information, and information is to communicate the truth.” This can be jarring for some Western viewers. But it is also useful; revolutionary films came to function in a similar fashion to violent resistance, disturbing thought patterns through a tool of rupture.

To avoid a hierarchy between the filmmaker and the subject, the PFU often billed its projects as the collective act of self-representation. Some film credits read, “This film is made by the following workers,” followed by a non-preferential listing of names, while others had no credits at all: the cameraperson and the freedom fighter indistinguishable—both laborers for a cause. This position also led to the building of international solidarity links with other leftist and national liberation movements through film. The members of the PFU and PCI collaborated with filmmakers in Yugoslavia and Chile, lent cameras to efforts in Eritrea and Oman during the Dhofar Rebellion, and assisted Yemeni filmmakers in organizing a documentary workers union.

One might expect the films of militant Palestinian cinema to be self-serious or unrelenting, in contrast to, say, the sardonic distance of Elia Suleiman or Arab futurism of Larissa Sansour, two contemporary Palestinian filmmakers. But the Palestinian films that emerged from that era were also playful and creative, often explicitly feminist and secular, and did not always come with the imprimatur of the PLO leadership—like in A Hundred Faces for a Single Day (1972), which satirized the Palestinian bourgeoisie for its collaboration with Israel. In this way, contemporary Palestinian filmmakers who skewer the Palestinian Authority or who imagine a single state without the shackles of misogyny lean on and improve upon this legacy.

But the clearest continuation of the militant filmmaking ethos today is no doubt the cell phone video, which has been a particularly powerful tool of Palestinian resistance, generating a collective public domain archive, available worldwide, of atrocities committed by the Israeli state, like its routine and growing arrests of children. Sometimes, this footage helps support larger experiments like those by Forensic Architecture, a research agency based out of the University of London, which used the thousands of images produced by Gazans during the 2018 Great March of Return to piece together the IDF’s murder of volunteer medic Rouzan al-Najjar and refute the subsequent Israeli whitewash.

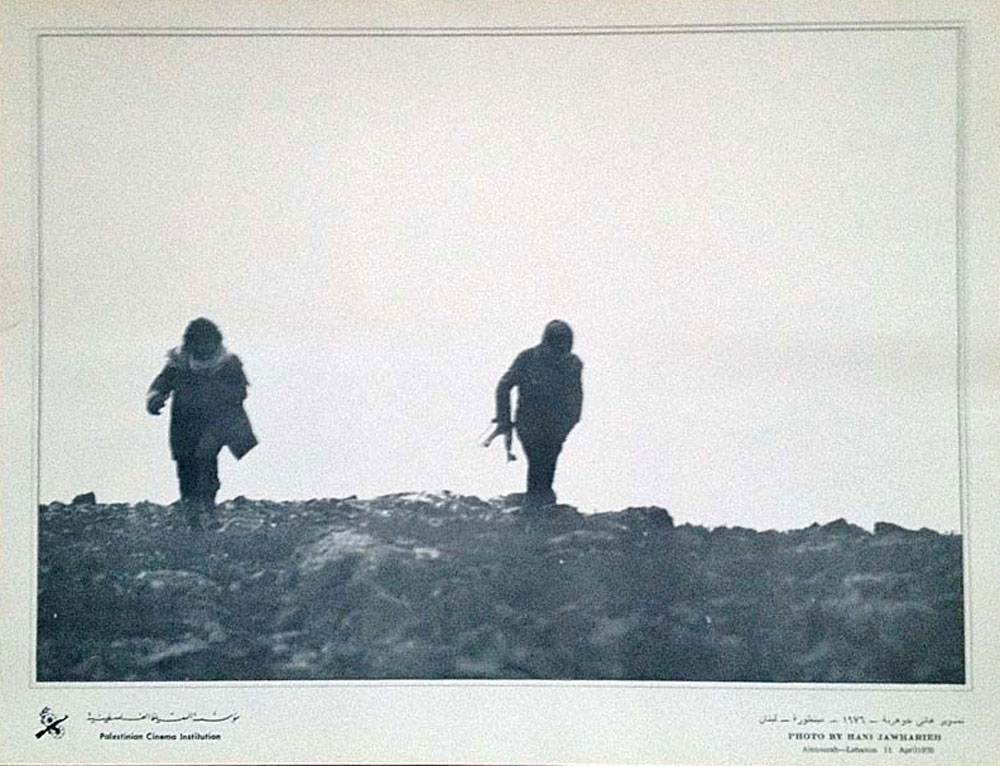

The three founders of the Palestine Film Unit are all now gone. Hani died in service to the PFU, killed by shelling in the Aintoura Mountains during the Lebanese Civil War. His death was memorialized by Abu Ali in a half-hour short called Palestine in the Eye (1976), which included interviews with Hani’s family and colleagues reflecting on his life, as well as footage of the moment of his death, which Hani had inadvertently caught on film.

Sulafa has perhaps the saddest story. Born in Nablus, she first picked up a camera in the girl scouts, and won a scholarship to study cinematography in Cairo in the mid-1960s. There, she fell in with the Palestinian Student Union, photographing fedayeen before they left to the field, in case they died and the PLO wanted to use their faces for posters. In 1970, Sulafa was accidentally shot by another Palestinian at the training camps and was partially paralyzed, prematurely ending her career. She died in 2002, having never made another film.

Loss is inherent to Palestinian life. The death of our mothers, our artists, our art is commonplace. Oftentimes, this develops in us a resilient constitution—a sumud—other times, a lasting grief. For some, the answer is to catalog those griefs, to put them on paper or on film, so that they can change minds or exist as memories. For others, this can only produce an unhealthy nostalgia. Palestinian director Mohanad Yaqubi’s Off Frame: AKA Revolution Until Victory (2015)—shown at the Brooklyn Academy of Music earlier this year, as part of its series on resistance cinema—uses found archival footage to explore how these discoveries alter our understanding of Palestine’s history. Implicitly, the film argues that while Palestinian cinema is inextricably linked to these casualties of the past, the creative potential of the archive does not always lie in the closure brought by rediscovery, but in the imagination made possible by the loss.

This is best encapsulated in the fascinating postscript to the story of They Do Not Exist. The fantasy of what was contained in the film’s last minute came to inhabit the minds of Palestinian artists and writers, becoming a stand-in for the question of that Palestinian chapter, unfinished, lost, meaning different things to different people. Some resourceful Palestinian researchers eventually found the last minute, and Annemarie Jacir (Emily Jacir’s sister) arranged the first-ever premiere of the lost film in Jerusalem, inviting Abu Ali in 2003 to watch his film in the capital city.

After forty-seven years of exile from Palestine, Abu Ali was now living in Ramallah. He had never been allowed back to his old home in Jerusalem because of the occupation, so, to get him to the premiere, the organizers smuggled him in by car. After speaking with Mohanad for this piece, he sent me a link to watch They Do Not Exist in full. I must admit I prefer the unfinished ending; sometimes the searching is the point.