In October 1991, when I was four years old, a sudden firestorm swept through my hometown of Oakland, California. My family watched from below as the homes in the hills above us were consumed. Pieces of ash littered our backyard, and the sky turned black with smoke. The fire was brought under control as the winds that had fueled it died down, but it left twenty-five dead and immense property damage.

For months afterward, we drove through a surreal and disturbing landscape on the way to my preschool: a scuffed refrigerator sitting in the center of a pile of ash, crumbling walls that looked more like castle ruins, a discoloration from the fire’s heat on everything that remained.

I wanted to fix it, so I got to work. I spent hours drawing variations of the same house over and over again: triangle-shaped roof, two to four windows (sometimes with flower boxes), and a door with a round knob. I was trying to undo the fire and rebuild the Oakland I knew. But by the time we moved away two years later, I’d lost interest in the project, distracted by new subjects and perhaps on some level embarrassed. Cute houses seemed to have no place in a boy’s repertoire.

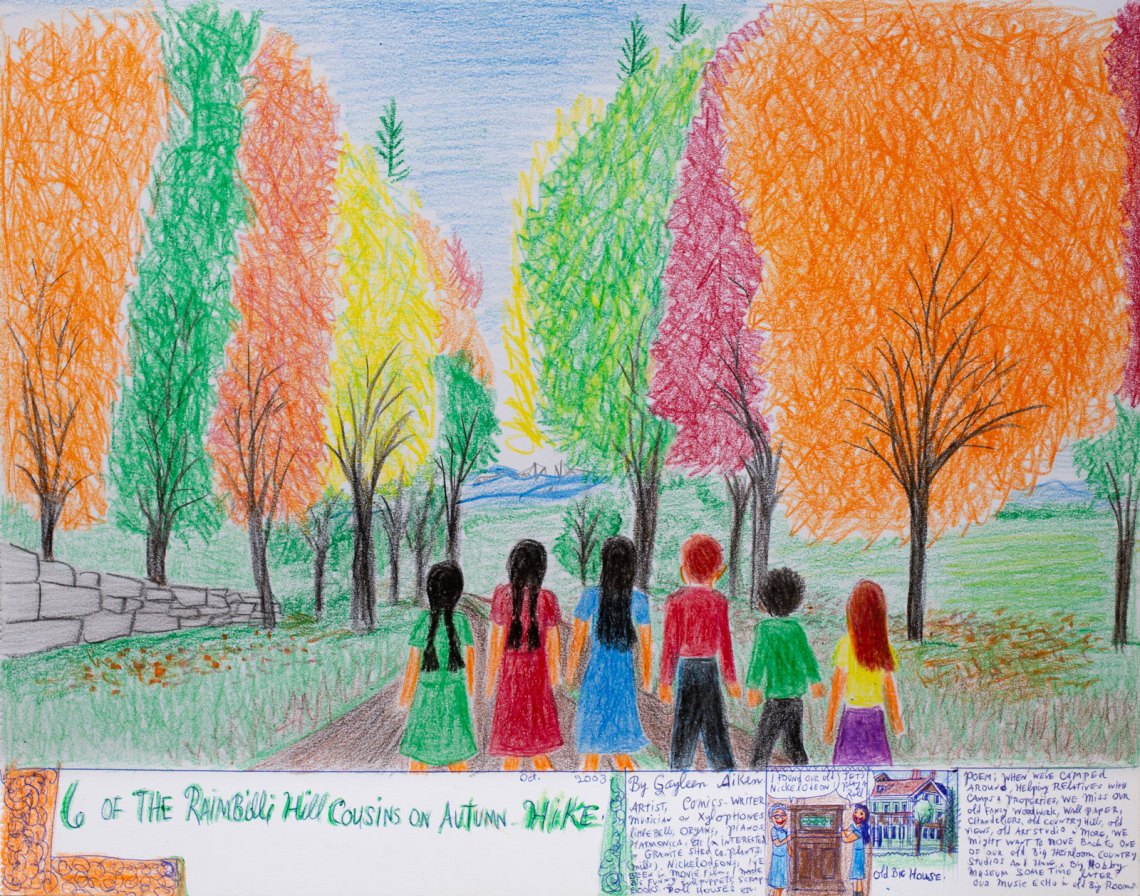

What does it look like when an artist never loses that early vision? The work of Gayleen Aiken provides a powerful example. Born in Barre, Vermont, in 1934, Aiken was an only child, raised by her parents in a three-story farmhouse. She began making art at an early age and invented a family of twenty-four cousins, named the Raimbillis, who appeared in her drawings and paintings throughout her life. Bullied in school, she dropped out after eighth grade and was homeschooled by her parents. Her father died when she was a teenager, and she and her mother were forced to sell the family house, at which point they moved into an apartment in Barre.

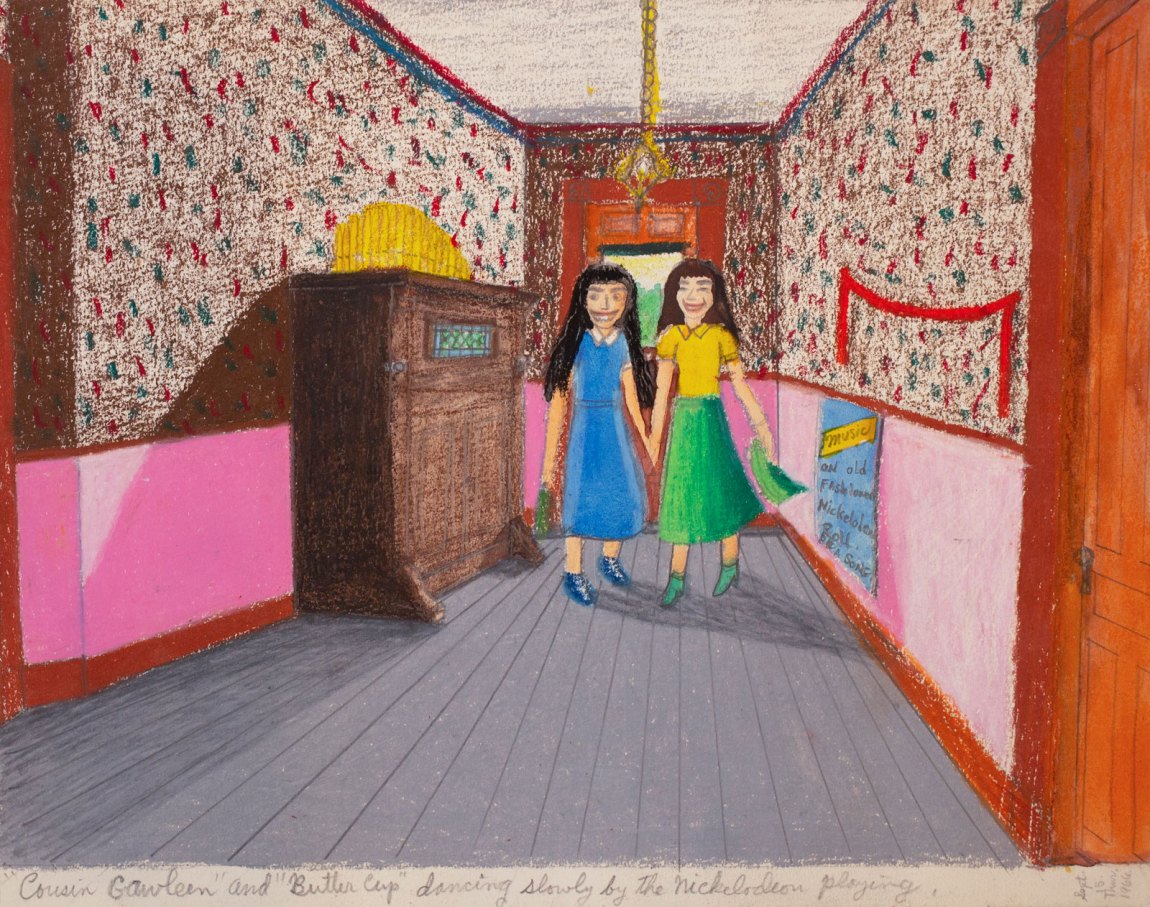

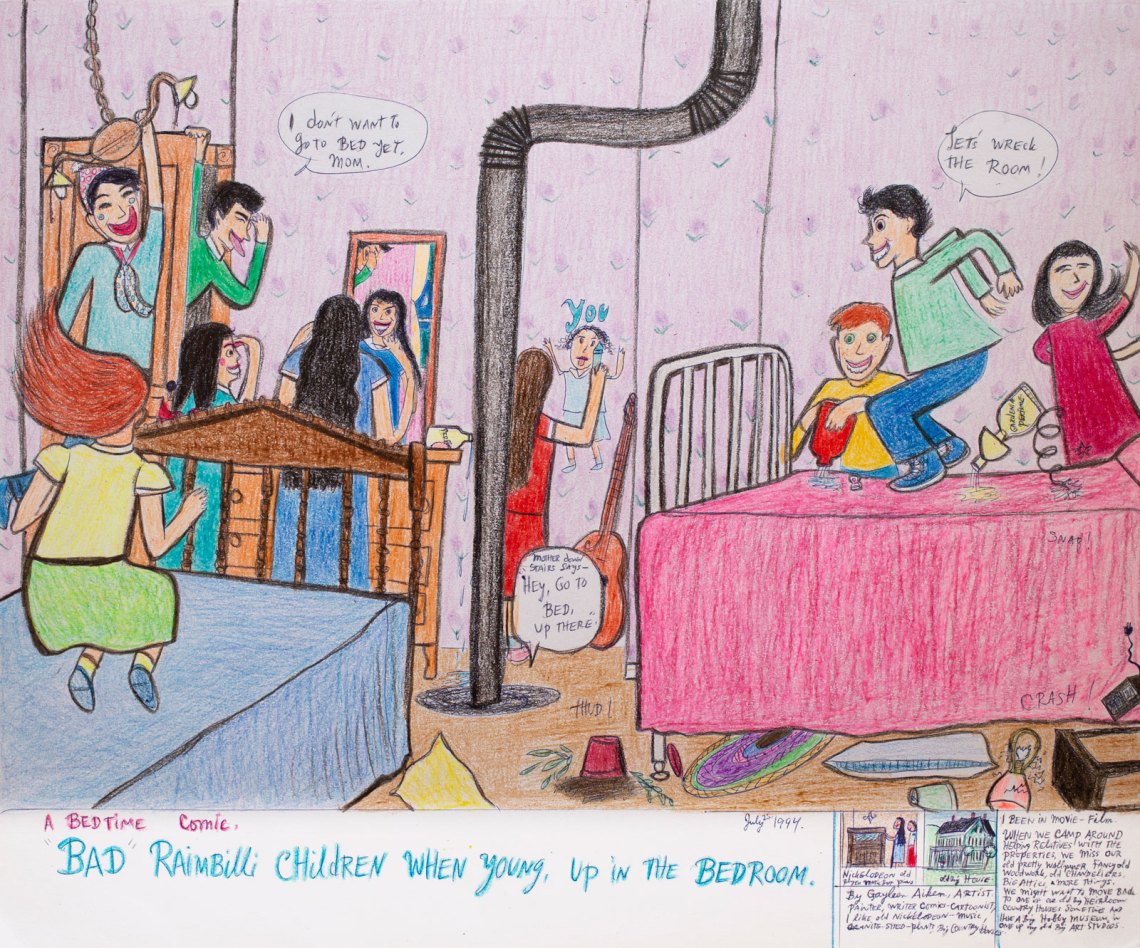

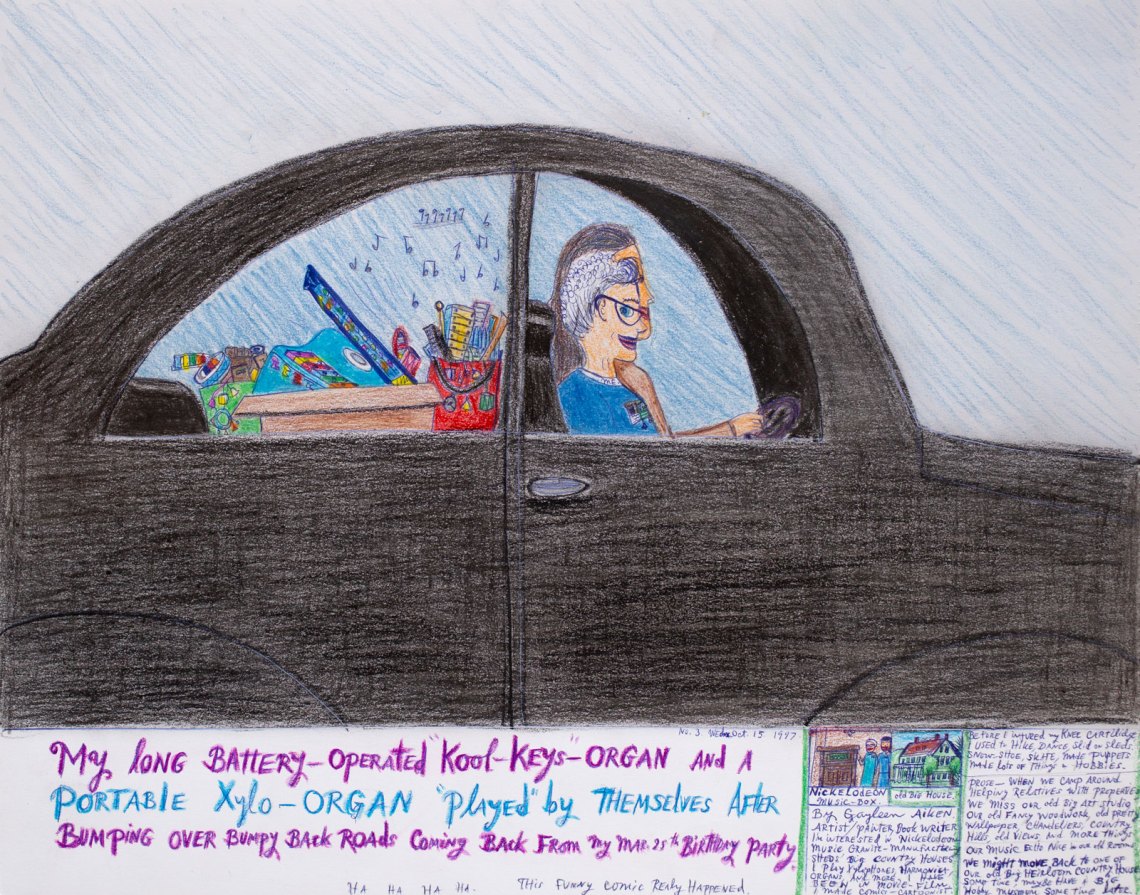

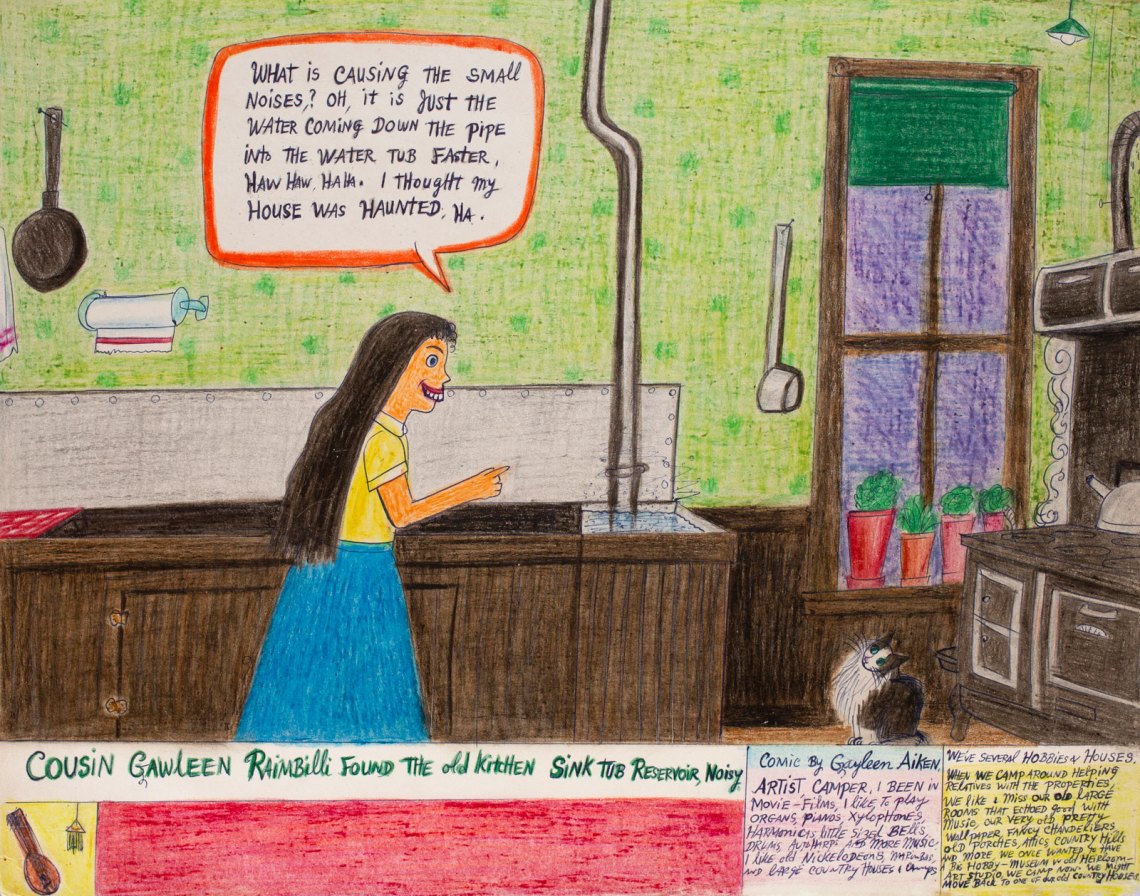

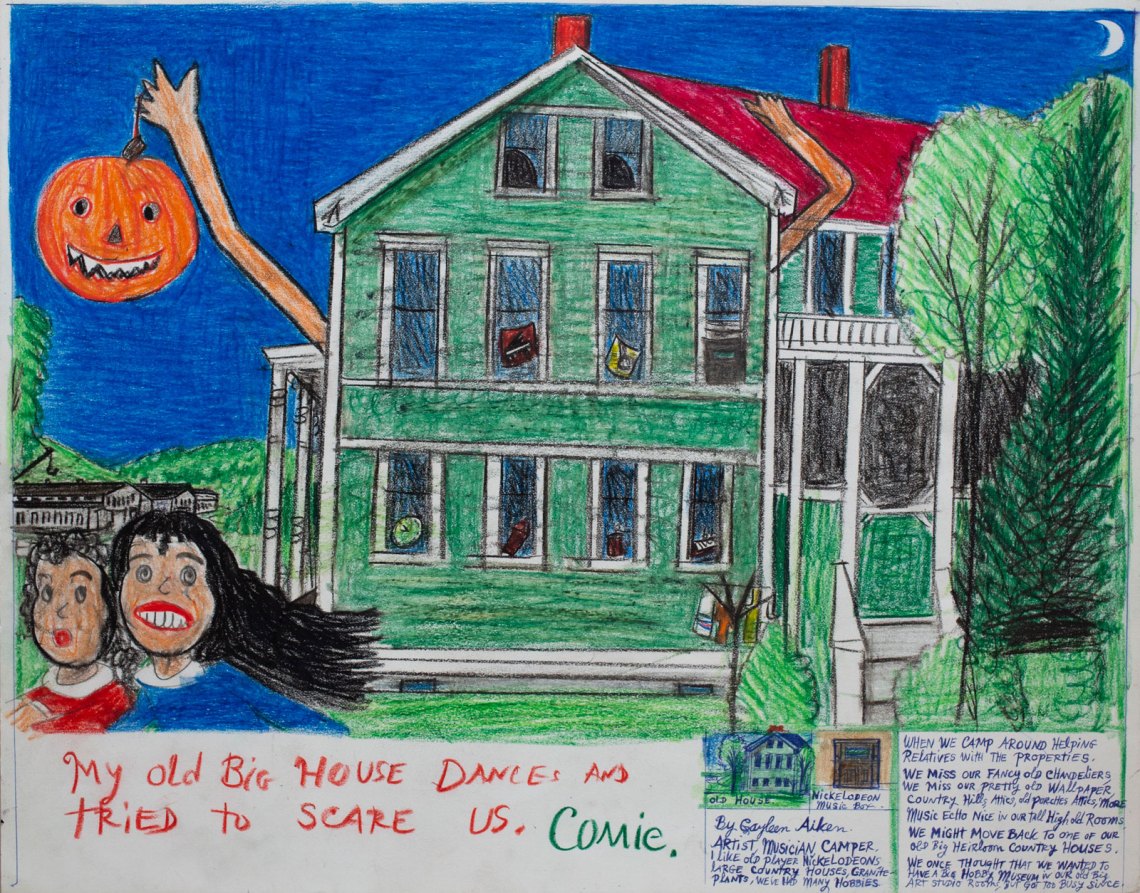

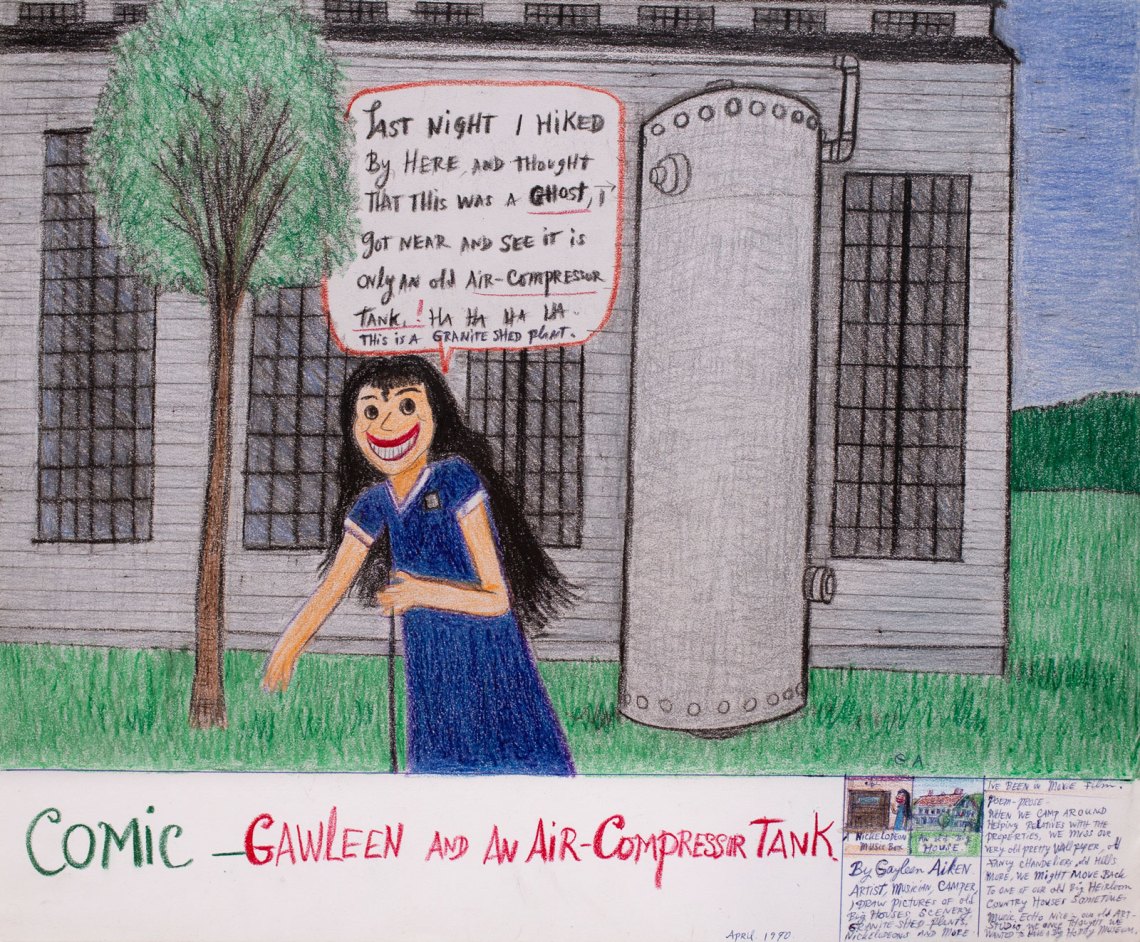

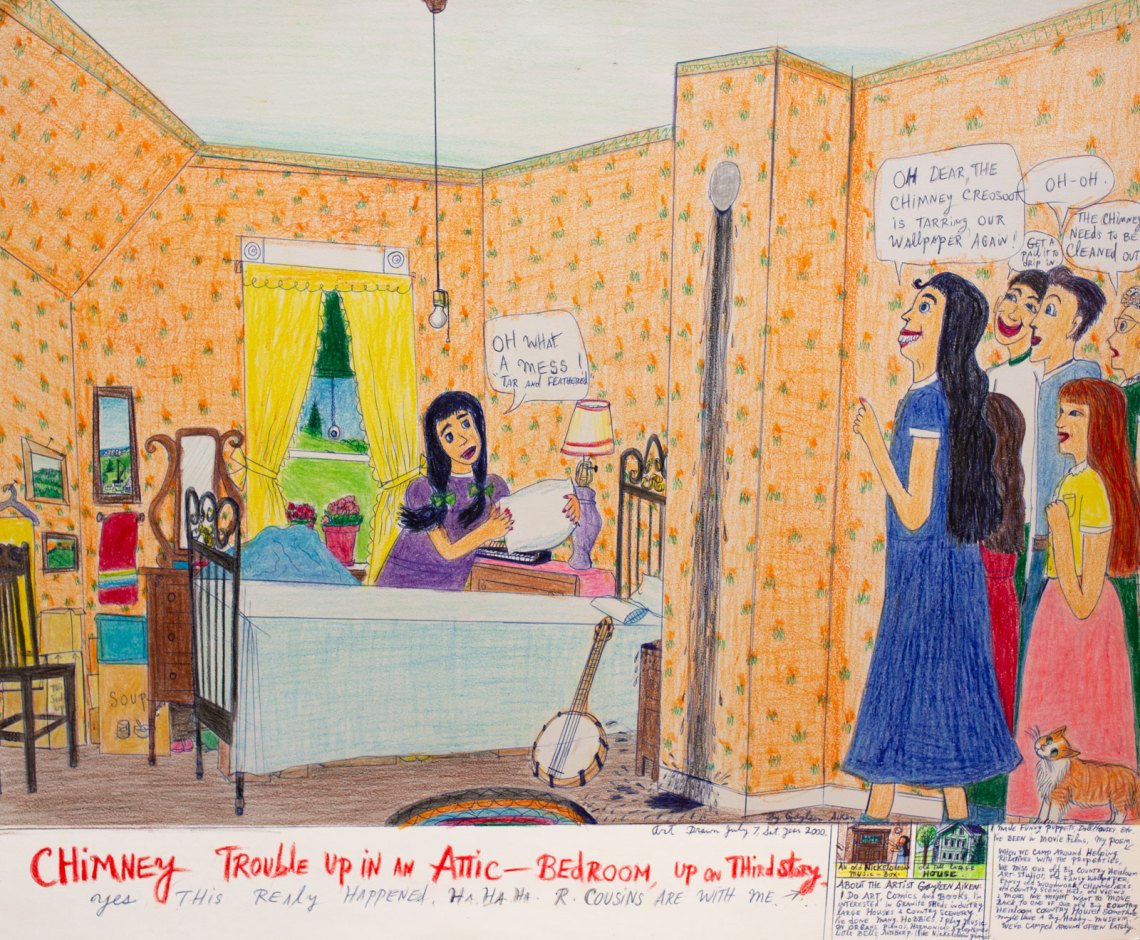

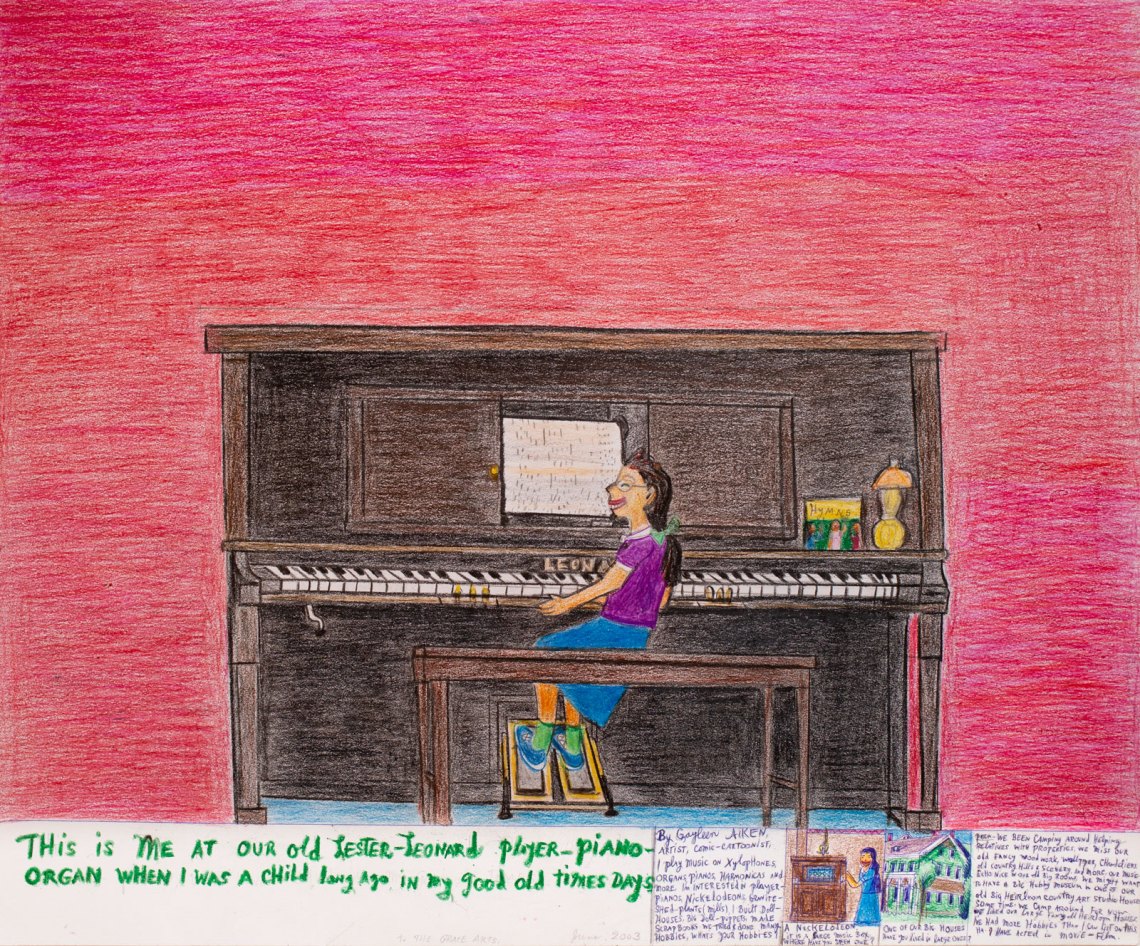

Aiken’s work is filled with bright, enthusiastic colors rendered in pencil, paint, crayon, and pen, often paired with dense handwritten text running across the bottom, like a cable news banner or a food nutrition label. Her images frequently include landscapes of the countryside, scenes from the local granite industry, and Aiken’s family (real and imagined), as well as interiors and exteriors of the farmhouse, seemingly returned to Aiken family ownership.

Some of Aiken’s drawings are on display in “Interiors,” a digital exhibition put on by the Manhattan art gallery Fort Gansevoort, curated by the artist Laurie Simmons. In a short essay that accompanies the exhibition, Simmons writes:

I think I fell in love with Gayleen Aiken’s work when I saw the interiors…. All my pictures from childhood to the present have addressed this, whether formally, literally, figuratively or abstractedly. What I loved about drawing and painting rooms when I was young was the freedom to make things up. Walls could be crimson or spring green (in fact, I made many detailed pictures of Dorothy’s green tinted life in the Emerald City). Furniture could hang from the ceiling or stick out from the walls.

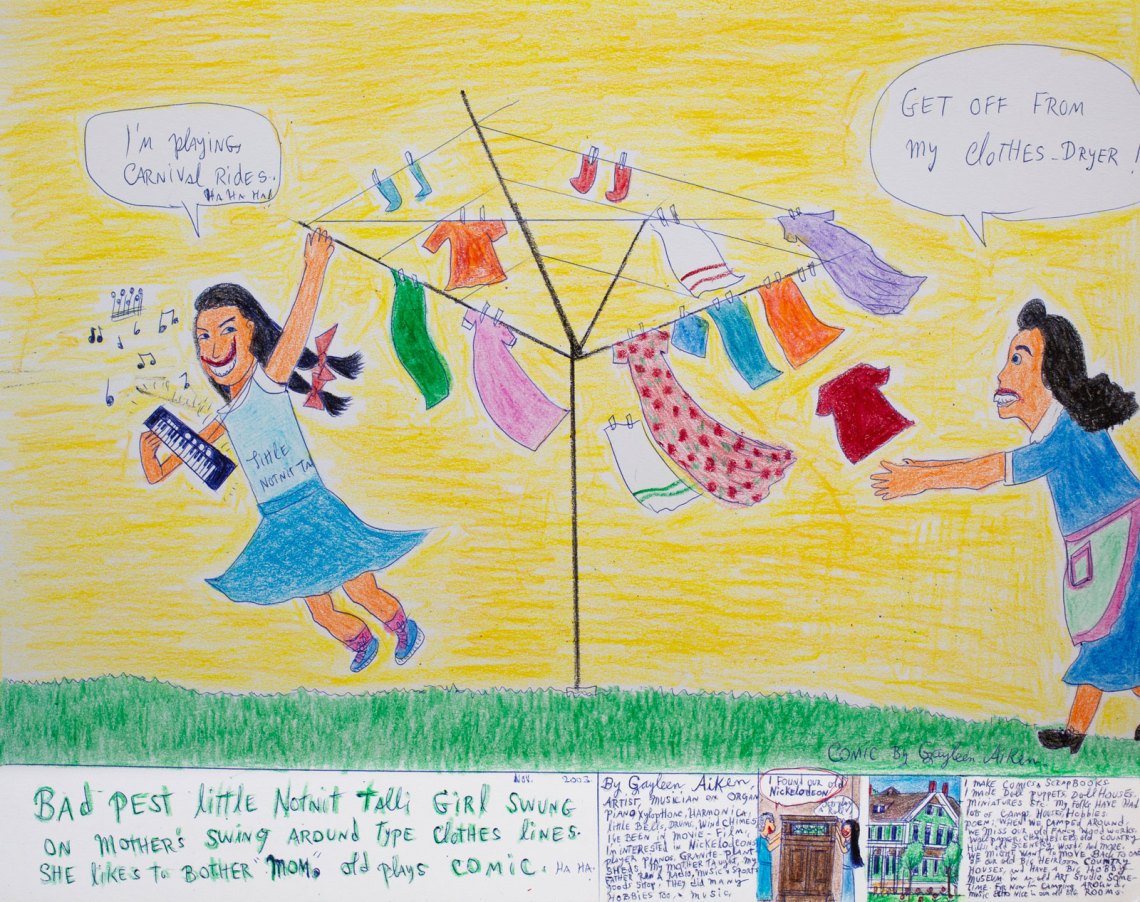

The images in “Interiors” teem with similar, elaborate assemblages: intricate wallpapers, family photos, granite tombstones, chandeliers, colorful lightbulbs, and numerous musical instruments, both working and broken. The titles are often rich and rambling stories themselves: My long battery-operated “Kool-Keys-” organ and a portable Xylo-Organ “played” by themselves after Bumping over Bumpy Back Roads coming back from my Mar. 25th Birthday Party, for example, or Bad pest little Notnit Talli Girl swung on mother’s swing around type clothes lines. She likes to bother “Mom”. old plays comic.

Aiken easily embraced the title “artist,” along with everything else she saw herself as, signing the front of a typical image at bottom right, “By Gayleen Aiken, artist, camper, comic book writer, musician, I like organ, piano, xylophone, nickelodeon–music boxes, large country houses.” Her comfort with the language of comics manifests in many of her works, such as “Nickel-Head” The New Player-Nickelodian Threw Out A Spit-Ball (paper) At A Man who Helps us, when it Rewound A Song Roll Fast, in which an innocent repairman of a player piano sees stars as he’s nailed in the head by a wad of paper, accompanied by the written sound effects “SPIT, WHAM!” Her collages—some of which can be seen on Fort Gansevoort’s website—are also striking, combining items as disparate as a string of sequins, clippings from a home furnishing catalog, a panel from the comic strip Blondie, and scraps of Aiken’s own drawings to create soothing scenes of domestic life, such as one of a child playing piano while a Raimbilli cousin looks on.

Advertisement

The Raimbillis, Aiken’s invented relatives, populate many of these spaces. Simmons describes the origins of the clan:

Gayleen created a complex world of imaginary friends. She claims she made up a story about them when she was 3 or 4 and they eventually became a group of roughly 24 perpetual teenagers…. They exist as both a group of life size cutouts and as characters in drawings, paintings and comic strips.

For anyone disappointed in the liveliness of their own relatives during the holidays, the giddy camaraderie of the Raimbillis is something to envy. Aiken draws playgrounds for her family and lets them run wild: a crowd of delighted cousins dance on the porch of a house at night in the neon green glow of a clock in Cousin Gawleen, Johnio, Gawliver…; a gang of them jump on beds, draw on the walls, and threaten to “wreck the room” in A Bedtime Comic: “Bad” Raimbilli Children When young, up in The Bedroom.

Aiken’s Vermont is not the Gothic New England of Shirley Jackson: all of the Raimbilli adventures are relatively safe, with easy resolutions. Cousin Gawleen (who appears to be a sort of Bizarro version of Gayleen, with a distinctive overbite grin) solves a mystery before the viewer can even investigate it in Cousin Gawleen Raimbilli Found The old Kitchen Sink tub Reservoir, Noisy. (1987). In the image, Gawleen points to a water pipe running from the ceiling to the sink and says, in a speech bubble, “What is causing the small noises,? OH, it is just the water coming down the pipe into the water tub faster, haw haw, ha ha. I thought my house was haunted, ha.”

We hear Aiken’s own voice speak that “haw haw” in Jay Craven’s 1985 documentary Gayleen, audio clips of which are included in the exhibition. Gayleen was filmed at Fox Hall, an empty Victorian manor near Lake Willoughby, in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, when Aiken was about fifty years old. We see her skipping through the fields of the estate with her Raimbilli cardboard cutouts in tow, blowing away on one of her many harmonicas, helping one of her cardboard cousins rock out on a xylophone, making a watercolor painting of a nickelodeon with speed and relish—all while describing her work in excited, rapid, run-on sentences:

I have so many boxes of books and comics I have written all my life, they’re very funny stories about the Raimbilli cousins, a funny old imaginary man that’s just a made up story, and a funny little girl imaginary story, but me and my little friend used to play Notnit Talli the bad little girl pestering Mom on the back porch…

Aiken’s work came to notice in the early 1980s, in part through Vermont’s Grass Roots Art and Community Effort (GRACE), an organization that provides art classes and materials to nursing homes, mental health centers, and adult day centers. Aiken befriended the founder of GRACE, the artist Don Sunseri, whom she gave some of her art to be exhibited and sold. She was the subject of a one-woman show at Lincoln Center in 1986, and today her work is in the collections of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art and the American Folk Art Museum.

Despite the acclaim she received later in her life, Aiken, who died in 2005 at the age of seventy-one, never again got to live in a farmhouse like the one she grew up in. She held out hope that the possibility was still there: “We might move back to one of our big country houses. I miss the wallpaper and the chandeliers—the better things that we used to have—and want to move back.”

Advertisement

She also never got to have the family she wanted: she was surrounded by the Raimbillis on the page but remained alone through her adult life. Sunseri said, in an interview that aired on Vermont Public Radio after Aiken died,

Gayleen [is] someone who shows us the power of imagination. She’ll make a drawing that starts out in her mind, I think, with a painful situation from her past, and she’ll change it into a comic situation. She’ll make it the way it should have been.