In September, The New York Times reported on a concerning surge in Russian ransomware attacks against the United States, including “against small towns, big cities and the contractors who run their voting systems,” the “full scale” of which “is not always disclosed.” Last week, the newspaper further reported that Russia “has in recent days hacked into state and local computer networks in breaches that could allow Moscow broader access to American voting infrastructure,” but said that “Russia’s ability to change vote tallies nationwide is limited,” a caveat that seems more ominous than reassuring. Meanwhile, public officials and voting-machine vendors historically have not always been forthcoming with the public about the extent of security weaknesses and breaches. Election security advocates worry that this lack of transparency may leave the public exposed both to potential election theft and to false claims that election theft has occurred. In an effort to mitigate these risks, grassroots efforts around the country seek to make the 2020 election more transparent than past elections.

In August 2016, according to David Shimer’s book Rigged, “the U.S. Intelligence community had reported that Russian hackers could edit actual vote tallies, according to four of Obama’s senior advisors.” But the only government official who publicly alluded to this possibility was then Senate minority leader Harry Reid. On August 29, 2016, Reid published a letter he’d sent to then FBI director James Comey in which he said the threat of Russian interference “is more extensive than is widely known and may include the intent to falsify official election results.”

Reid has said that he believes vote tallies were changed in 2016. According to Rigged, “Obama’s leading advisors dismissed Reid’s theory, with a catch: they could not rule it out.” James Clapper, Obama’s director of national intelligence, told Shimer: “We saw no evidence of interference in voter tallying, not to say that there wasn’t, we just didn’t see any evidence.”

According to Rigged, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) did not have independent surveillance abilities and just thirty-six local election offices had let them assess the security of their voting systems before the 2016 election. In January 2017, the DHS confirmed that it had conducted no forensic analysis to verify that vote tallies weren’t altered. In June 2017, it again confirmed that it had conducted no such forensic analysis and did not intend to do so. Senator Ron Wyden, Democrat of Oregon, has since said that “As far as I can tell, no systematic post-election forensic examination of these voting machines took place. Whatever the reason for this failure to act, this administration cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of 2016.”

Also in June 2017, The Intercept reported that Russia had attacked our election infrastructure and that the attack was more pervasive than either the Obama or Trump administrations had let on—based on a classified report leaked to the publication by Reality Winner, a twenty-eight-year-old Air Force veteran and National Security Agency contractor. Unfortunately for her, The Intercept published the document in such a way that the FBI was able to identify the source of the leak; Winner was arrested and tried under the Espionage Act. Sentenced to five years in prison, she is still serving her term.

In his duty to report a threat to the republic, the FBI’s director was infinitely less forthcoming than Winner. In September 2016, James Comey testified to Congress that “the vote system in the United States…is very, very hard to hack into” because “[t]hese things are not connected to the Internet.” The same month, the former Elections Initiatives director for Pew Charitable Trusts told Congress that “I know of no jurisdiction where voting machines are connected to the Internet. This makes it nearly impossible for a remote hacker.” Numerous other individuals, including Thomas Hicks, who has served as chairman of the US Election Assistance Commission (EAC) since 2014, have also told Congress that voting machines are not connected to the Internet.

Such reassurances were deeply misleading.

Before each election, all voting machines must be programmed with new ballots. They typically receive this programming via removable memory cards from county election management systems or computers outsourced to third parties. According to election security expert J. Alex Halderman and others, most election management systems can and likely do connect to the Internet from time to time or receive data from other, Internet-connected systems. In Halderman’s view, according to the tech news site Cyberscoop, “a determined attacker could spearphish the individuals responsible for programming the ballots and infect their devices with [vote-changing] malware” that could spread via the memory cards to all of the voting machines in a county or state; and “there’s little visibility into how officials or third parties manage the ballot programming process and whether they use cybersecurity best practices.”

Advertisement

Furthermore, Wisconsin and Florida approved in 2015 the installation of cellular modems in their Election Systems & Software (ES&S) precinct ballot scanners, which are used to count paper ballots (whether marked by hand or with a touchscreen). Poll workers use these modems to transfer unofficial vote totals from the precincts to the county election management systems (which include the county central tabulators) on election night. Official results are typically still transferred from precincts using memory cards or other removable media that are transported to the counties, a so-called sneakernet. Election security experts strongly advise against using cellular modems to transfer unofficial results because they say this practice provides an unnecessary opening for foreign nations and other remote attackers to infiltrate counties’ central tabulation systems. After breaching such tabulators, a hacker could install malware to change not only the unofficial vote tallies but also the official ones.

Federal guidelines for voting equipment are voluntary and do not currently bar the use of cellular modems. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) assists the EAC in developing these guidelines, and the agency is working on the next generation of them. According to a recent report in the Palm Beach Post, a NIST official cautioned the EAC in December 2019 that the use of wireless devices “make the voting system a node on the internet” that “could provide an entryway for remote attackers.”

Vendors and many election officials have ignored such warnings, sometimes claiming (falsely) that cellular transmissions don’t connect to the Internet. Other times, they claim that the connection is so brief that it doesn’t matter. But experts say that exposing an election system to the Internet even briefly on election night provides enough time for a determined attacker lying in wait to enter the system.

Last year, cybersecurity journalist Kim Zetter reported that a team of election security experts led by Kevin Skoglund had discovered that some election systems on the receiving end of these modem transmissions had been left online for months and perhaps years, not just a few seconds. These include systems in Florida (seven counties, including Miami-Dade), Michigan (four counties), and Wisconsin (nine counties).

In September this year, these same states received a letter signed by nearly thirty election security experts and election integrity organizations, recommending that election officials remove these modems. Susan Greenhalgh, the senior election security adviser for the nonprofit Free Speech for People, who led the initiative, told me that these swing state officials have not responded to the letters. Ion Sancho, who served as the supervisor of elections for Leon County, Florida, for almost thirty years and appears in the documentary films Hacking Democracy and Kill Chain, recently wrote follow-up letters to Florida county election officials in a final attempt to persuade them not to use the modems and to disconnect central servers from the Internet.

*

Of course, it’s not just foreign powers that we must worry about. As cybersecurity journalist Brad Friedman told me, “an election commission headed up by President Jimmy Carter found after the controversy surrounding the secret tabulation of the election in Ohio in 2004, that election insiders remain the greatest threat to our elections.” Election management systems, voting machines, memory cards, and USB sticks are among the many things that election insiders could corrupt. The software used in voting machines and election management systems is proprietary to the vendors, making it difficult to obtain permission to forensically analyze them. Experts say hackers could erase their tracks anyway. As a practical matter, the only way to know if electronic vote tallies are legitimate is to conduct full manual recounts or robust manual audits using a reliable paper trail. But most jurisdictions require manual recounts, if at all, only if the margin of victory is less than 0.5 percent. Thus, after the 2016 election, many experts and advocacy groups recommended legislation requiring robust manual election audits in 2020.

Earlier this year, though, Republicans blocked federal legislation, the SAFE Act, which would have required such audits for most federal races. America’s preeminent election-auditing expert, Philip Stark, a professor of statistics at the University of California at Berkeley, told me a few weeks ago that “only a few jurisdictions currently audit elections in a way that has a good chance of catching and correcting wrong reported outcomes. That requires a trustworthy paper trail—primarily hand-marked paper ballots kept demonstrably secure throughout the election and the audit—and [what is known as] a risk-limiting audit using that paper trail. But, to the best of my knowledge, even those states only audit a few contests in each election.” (Emphasis added.) A report by the National Conference of State Legislators confirms that just three states (Colorado, Rhode Island, and Virginia) require risk-limiting audits for one or more races.

Advertisement

As I have previously reported, many election officials have also dispensed with hand-marked paper ballots (pen and paper) in favor of new touchscreen voting machines called ballot-marking devices (BMDs). If voters miss machine errors or omissions on the paper voter records marked by these touchscreens (some call them “paper ballots,” misleadingly), a risk-limiting audit can’t detect that. A recent study found that voters themselves detected only 7 percent of such inaccuracies. According to Halderman, who led the study, even when a poll worker prompted voters to verify the printouts, they detected only 15 percent of such inaccuracies. The only measure that made a big difference was giving voters prefilled slates, such as completed sample ballots, to compare against the printout—at which point voters detected 73 percent of such inaccuracies. It is doubtful many voters know to ask for such a thing.

In February, the Associated Press reported that BMDs would be used by all in-person voters in four hundred counties in sixteen states. Pennsylvania, a crucial battleground state, will deploy them in two of its most populous counties, Northampton and Philadelphia, despite huge problems with them last year. In Philadelphia, per a Reuters report, “Poll workers and technicians reported issues with the new machines at more than 40 percent of polling locations,” yet the voting machine vendor ES&S said that “it was ‘simply inaccurate’ for anyone to imply there were widespread issues.” In Northampton, which has been described as potentially dispositive in Pennsylvania’s presidential race, the local Republican Party chairwoman said that the results of a November 2019 election “can’t be trusted” because of the catastrophic failure of the machines on that occasion. “We think voters were disenfranchised,” she said.

Georgia, which is the only state in the nation with two Senate seats on the ballot, will deploy BMDs statewide in this election. Earlier this month, as reported by PBS News, a few counties found that the touchscreens were intermittently omitting some senatorial candidates from the review screens. The vendor claims to have fixed the problem by installing a last-minute software update on every machine in the state. Georgia’s secretary of state claims that voters can have confidence because it will conduct election audits starting in November. But per a recently adopted election rule, the state plans to audit just one race, chosen by the secretary of state, not at random. According to the Open Source Election Technology (OSET) Institute, Georgia lacks sufficient backup paper ballots in the event that these touchscreens fail.

Voter registration systems also raise transparency and security concerns. In 2019, it was reported that Russia had in 2016 breached Florida voter registration systems in Washington County, as well as at least one other county (Florida officials were obliged to sign a nondisclosure agreement as to the identity of that second county). The FBI told Florida lawmakers that it could not assess with certainty whether or not voter data had been changed.

Since the 2016 election, most states have installed devices to detect efforts at voter registration system intrusion, known as Albert sensors (after Albert Einstein), as a primary defense against hacking. As reported by Bloomberg in 2018, these sensors “have a knack for detecting intrusions like those from Russian hackers” and “funnel suspicious information to a federal–state information-sharing center,” known as the Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing and Analysis Center (an agency run by the Center for Internet Security, which Reuters describes as “a nonprofit that helps governments, businesses and organizations fight computer intrusions”). Per Bloomberg, Albert sensors are “intended to help identify malign behavior and alert states quickly.” But they “can’t block a suspected attack,” and “experts caution that they’re not deployed to most of the 9,000 local jurisdictions where votes are actually cast, and sophisticated hackers can sneak past the sensors undetected.”

Similar security concerns plague electronic pollbooks, the tablet computers that poll workers use to check in voters and, more recently, also to activate the new touchscreen voting machines adopted in Georgia and elsewhere. Although all electronic election equipment is vulnerable, electronic pollbooks are particularly risky because they often rely on a Wi-Fi or Bluetooth connection. Despite these reliability and security issues, use of electronic pollbooks has risen significantly since 2016. In the 2018 midterm election, ES&S electronic pollbooks in Indiana failed due to connectivity issues in five out of seven of the counties that used them; one county clerk called it the worst election she’d ever experienced in her eight years on the job. In Los Angeles County in March 2020, connectivity problems with new electronic pollbooks from a company called KnowInk wreaked havoc, causing delays in voting lines of as long as five hours.

Using electronic pollbooks to activate voting machines creates additional risks. According to PBS, e-pollbooks also caused problems, including displaying the wrong races and randomly shutting down, during Georgia’s primary elections in June. Again, the electronic pollbooks were supplied by KnowInk, whose managing director, Scott Leiendecker, is a former Republican election official. Leiendecker’s wife donated to the campaign of Georgia’s Republican secretary of state before the state announced its contract with KnowInk. KnowInk’s product manager once campaigned for Ed Martin, the president of the Phyllis Schlafly Eagles, which opposes the Equal Rights Amendment. KnowInk’s products are now used in twenty-three states, as well as Canada.

Nor can we count on officials to tell the public if e-pollbooks or other systems are breached. In January this year, the FBI announced a “change of policy,” whereby it will alert state election officials of local election system breaches. It has not explained why it lacked such a policy previously. Nor has it committed to informing the public of breaches even after investigations have concluded. On August 4, 2020, Senator Richard Blumenthal, Democrat of Connecticut, posted on Twitter that he was “shocked and appalled” after leaving a “90-minute classified briefing on foreign malign threats to our elections.” He wrote that “Americans need to see & hear these reports,” which, he said, ranged from “spying to sabotage,” yet Congress had been “sworn to secrecy—unacceptably.” Later that month, Trump and his appointee intelligence leaders cancelled in-person congressional briefings about Russian interference, alleging prior improper “leaks” by Democrats.

*

For his part, President Trump has deflected justified concerns about Russian hacking with unsubstantiated and fantastical claims about vote-by-mail. This includes the notion that foreign countries could counterfeit millions of mail ballots, which is not even a plausible method of fraud since election workers check mail ballots against voter registration lists. The theory was initially floated by Attorney General William Barr, who has admitted he has no actual evidence for it.

Earlier this month, Trump’s partisan director of national intelligence, John Ratcliffe, who cancelled the congressional briefings on Russian interference, held a press conference, emphasizing that both Russia and Iran had obtained voter registration data, and stating that Iran had faked menacing emails from the far-right group the Proud Boys to voters. But voter registration data is publicly available in many states, and Ratcliffe did not say whether systems had been breached to acquire it. A few days later, The New York Times reported that “many intelligence officials said they remained far more concerned about Russia [rather than Iran], which has in recent days hacked into state and local computer networks in breaches that could allow Moscow broader access to American voting infrastructure.” Similarly, in August, House majority leader Nancy Pelosi and Intelligence Committee chairman Adam Schiff warned that “the actions of Russia, China and Iran are not the same. Only one country—Russia—is actively undertaking a range of measures to undermine the presidential election and secure the outcome that the Kremlin sees as best serving its interest.”

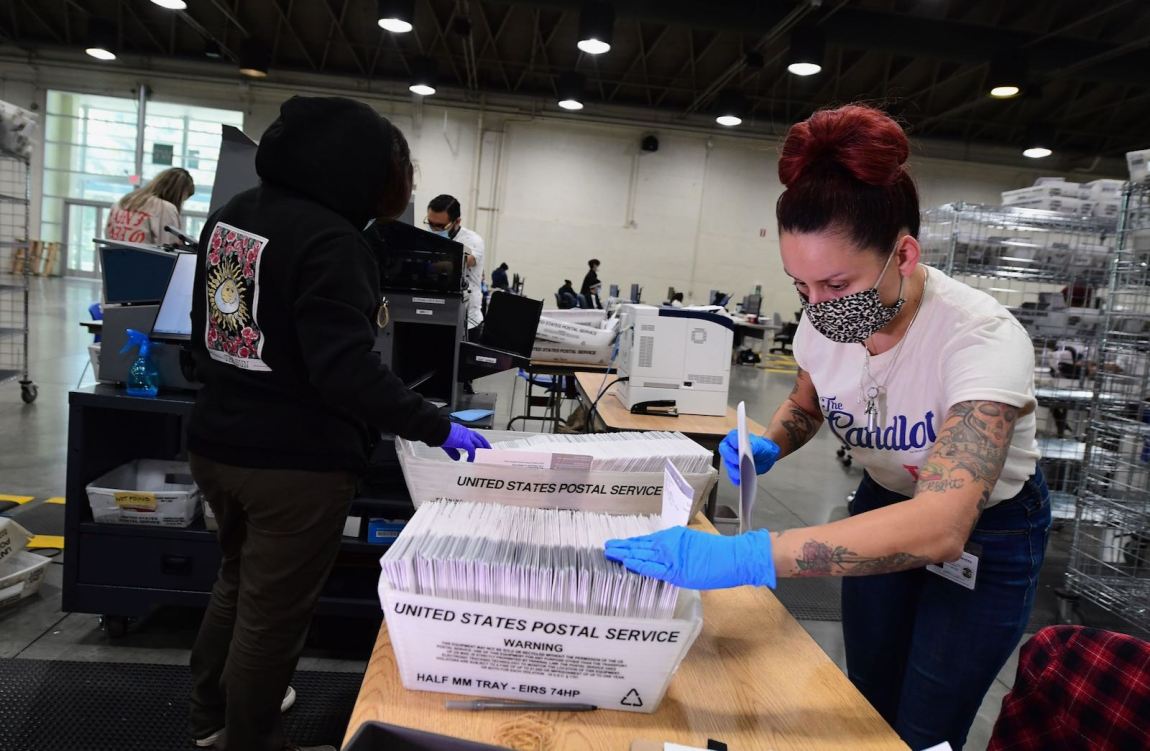

Heading into this election, election security activists are seeking to counteract this lack of transparency regarding the electronic aspects of our election system. Protect Our Votes (a group I cofounded), Democracy Counts, and Transparent Elections North Carolina are all organizing volunteers to photograph precinct totals—as shown on precinct poll tapes—after polls close, and then compare them with the official reported totals for those precincts. Although these comparisons cannot detect hacking of precinct tallies, a discrepancy between precinct totals and reported totals could indicate hacking or other problems involving the county central tabulators.

In late 2015, a poll tape analysis conducted by Bennie Smith, an election commissioner in Shelby County, Tennessee, revealed that votes had disappeared from voting machines serviced and maintained by ES&S in predominantly African-American precincts during the county’s municipal election held in October that year. The Republican county election administrator, Richard Holden, who had previously been investigated by the FBI, abruptly retired after Bloomberg reported the incident. A wave of electoral victories by African-American Democratic candidates for county office soon followed. This was a striking change from Holden’s six-year tenure, during which Republicans had twice swept nearly all countywide races.

Earlier this year, an election integrity group known as Audit USA led efforts to stop Shelby County’s Republican-led election commission from entering into another contract with ES&S. The county’s Democratic-led funding commission blocked the contract on October 12 amid concerns about the bidding process. But Smith, a Democrat, told me that Tennessee’s Republican secretary of state, Tre Hargett, has since given the county election commission new ES&S scanners for use in November’s election. Smith said he has not been able to ascertain whether these eleventh-hour scanners include modems, a measure he said would violate state law.

Elsewhere, an organization named Scrutineers does voter education work that includes various election transparency projects. One such project, called Ask the Voters, aims to conduct postelection affidavit audits of precincts or small counties with anomalous results. Another organization to which I belong, the National Voting Rights Task Force (NVRTF), will document live reported vote totals at crucial states’ county websites to capture evidence of any anomalies, such as vanishing votes. NVRTF’s software program will automatically capture screenshots of the reported results every fifteen minutes. (The citizen task force is still seeking volunteers to assist with this aptly named “Watch the Counties” project.)

Meanwhile, the Columbus Institute for Contemporary Journalism has sent requests to every county in seven states (Florida, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, and North Carolina) to obtain detailed information about the election equipment they are using and who specifically is programming it. The organization is preparing to file lawsuits where viable in the event of election anomalies this November.

In addition, most digital scanners in use today automatically create images of the paper ballots, which can be used by the public to compare against electronic totals. Unfortunately, many election officials erase them, but at this election, Audit USA and Citizens Oversight are leading an effort to obtain these images and compare them with official election results.

Finally, voters can report malfunctioning election equipment, voter suppression actions, and other problems to See Say 2020, which will vet these reports and post details of incidents on an interactive map, both to inform the public and to serve as potential evidence if official results need contesting.

In an ideal world, such independent monitoring efforts and citizen initiatives would not be necessary. Americans could go to the polls, vote, and be sure their ballots would be counted in a free and fair election. But that is not the reality. Instead, we face an unprecedented combination of election interference from hostile foreign powers and a president intent on keeping the public confused and uninformed about threats to our election infrastructure. As another US president liked to say: trust, but verify.