Shutters guarded the airport shops when I got to Vienna. Through the plastic coverings, you could see abandoned Sacher tortes and Mozart magnets, postcards with strapping Alpine blondes, and T-shirts reminding us that there are no kangaroos in Austria. Everything was sparklingly clean, but there was a Pompeii feeling to this place. Instead of a lupanar, there was a Starbucks; instead of a Villa of the Papyri, a Jamie Oliver franchise. I was in the ruins of an empire—that world of frequent flying I once inhabited, and assumed would last forever. On the departure boards, in those late-night connections to Podgorica and Brno and Sibiu, was another world of yesterday. (I was grateful that I didn’t have to wait for the 4:10 AM to Tuzla.) On those screens glowed the old empire of the Habsburgs.

I had a long layover before my flight to Sarajevo. It felt right that, as in olden days, it was hard to get there. The day before, a nurse had shoved a stick up one of my nostrils; Bosnia’s entry requirements mandated a Covid-19 test not more than forty-eight hours old. Then, on the first night I was there, the president of my home country, France, announced another lockdown. In pandemic terms, Bosnia was safer than many countries with a less fearsome history—an affable shade of peach on an angry red map of infection rates. But friends were alarmed: this was no time to take nonessential trips. Yes, it was an honor to have a book translated, they said, but that did not make it an essential trip. It was hard to explain why it seemed essential to me.

And I wasn’t daunted by the difficulties of getting there. Though only an hour from Vienna or Milan, and though it begins within sight of the shiny tourist islands of the Dalmatian coast, Bosnia has always stood apart—“Oriental” is the word the old travel writers used—its borders marking the farthest advance of Turkey into Europe. Just beyond the steep mountains that line the Mediterranean, it lurks—an unassimilable fastness.

In Yugoslav novelist Ivo Andrić’s Bosnian Chronicle, set in the small city of Travnik during the age of “Bunaparta,” the French consul complains about the Bosnians: “This people has some kind of incomprehensible, perverse hatred of roads.” His secretary explains that the Christians fear roads because they will let the Turks in: “Sir, the worse the roads, the rarer our Turkish visitors.” The sentiment is mutual. For the Turks, too, “every link with Christian countries amounts to opening the doors to hostile influence.”

*

I first went to Sarajevo in 2013. It was a smooth jump from the city of waltzes. But as soon as I got there, I found myself on one of the world’s most notorious roads, the long avenue that led from the airport to the center of town. It was called Zmaja od Bosne, but during my youth—when, for several years, it was on television practically every day—it had been known as Sniper Alley. Wide, straight, exposed to artillery fire from nearby mountains, it was a gauntlet that anyone trying to enter or leave the besieged city had to run.

My main memory of the wars that destroyed Yugoslavia was how long they lasted, from 1991 to 1999. Throughout high school and my years in college, we heard about this conflict in a place that—it was always said—was in the heart of Europe. I knew Sarajevo suffered the longest siege in modern history, twice as long as the Nazi blockade of Leningrad in World War II. I remembered footage of people huddled in doorways, hoping shells would land somewhere else. I remembered the images of men in concentration camps, and women digging through mass graves with bare hands, searching for sons, brothers, husbands.

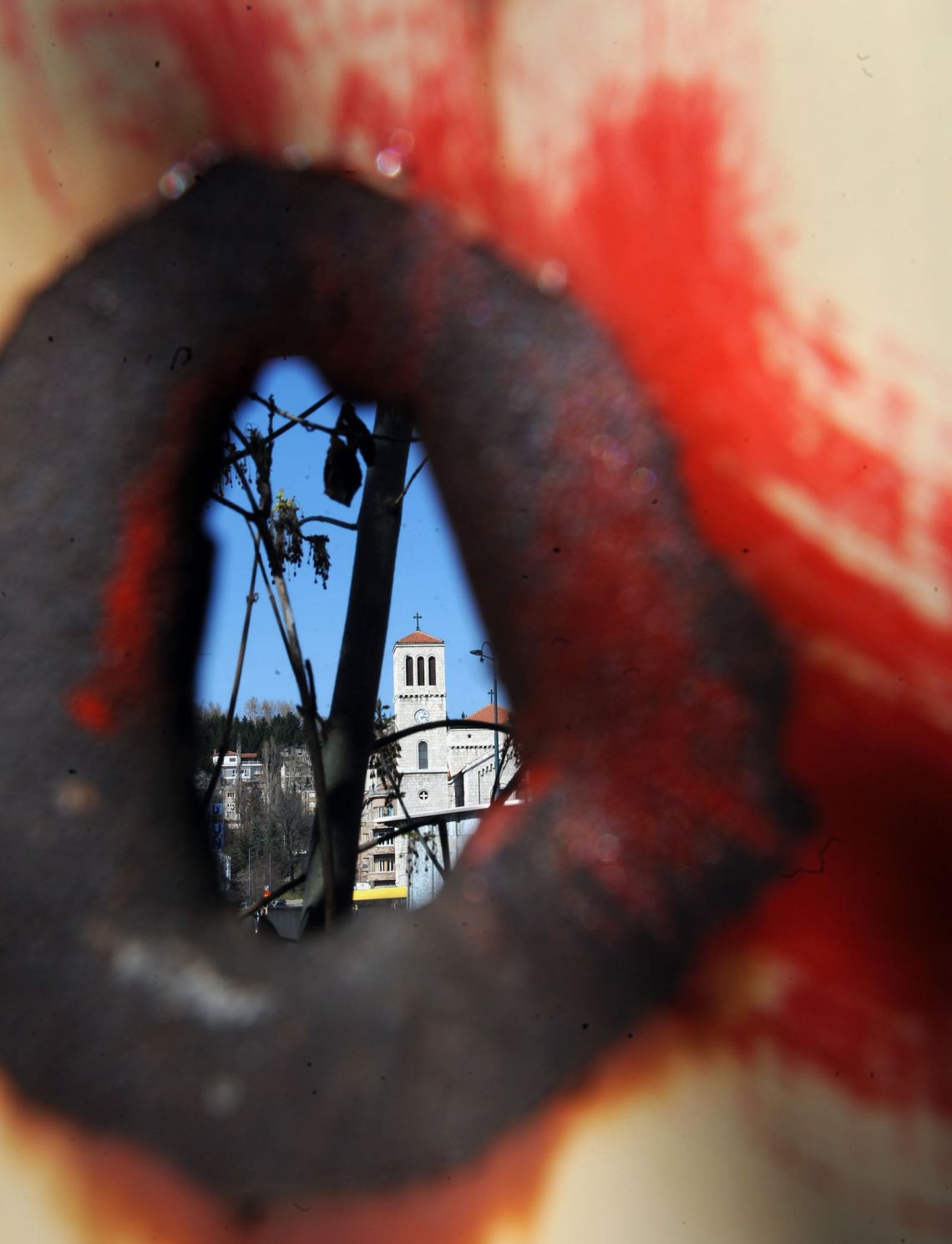

I arrived in 2013, eighteen years and a whole generation later. Sarajevo still bore the scars: there were bullet holes in nearly every wall, the only buildings without war damage the embassies and hotels. “Nobody cares about this country,” the Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr told me.

I was there because of one person who had. The year before, when I decided to write a biography of Susan Sontag, it was hard to know where to start. Where in her work, where in the archives, where among her hundreds of friends (and enemies). But also where. In her generation, no American writer lived such a dizzyingly international life: she’d made movies in Stockholm and created scandals in Bogotá; she dated a duchess from Naples and a playwright from Havana; her sister lived in Maui and her granddaughter lived in Paris. But I quickly understood that no place was so central to her legacy as Sarajevo.

When this was the worst place in the world, amid a genocide, she came no fewer than eleven times. Why? To put on a play, Waiting for Godot. In doing so, she became a Bosnian icon. The square in front of Bosnia’s National Theater is not named for the politicians like Bill Clinton or Tony Blair, who belatedly helped to end the carnage. Instead, it’s called Pozorišni Trg Susan Sontag, after the woman who put on a play.

Advertisement

Really, half a play: Sontag’s Godot ended with Act I.

*

During that first visit, when I came to interview surviving members of the cast, I found a still-living presence. Here, Sontag was less the pope she seemed to be in Manhattan. The stories were more personal. One woman told me how, in the middle of the siege, when an onion was considered a generous gift, Susan brought her a huge bottle of Chanel No. 5. An actor remembered that, for his daughter’s birthday, Susan gave him half a watermelon, which, back then, was “as if someone would give you a brand-new Mercedes!”

After a few days in the city, I thought that I had been spending too much time with the usual suspects—intellectuals, journalists, filmmakers—and wondered how much, if anything, regular people knew about her. I asked a woman selling vegetables if the name meant anything to her. She was offended. “The propaganda against us was so strong that if she hadn’t told the truth about what was happening to us, nobody would have believed it. If I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes, I wouldn’t have believed it myself.”

During the seven years I worked on the biography, I often thought of that woman, and the other people I met in Sarajevo. In New York, people tended to focus on Sontag’s extreme personality. I grew wary of all the “Susan stories,” though it was fascinating to see how Sontag—then dead for less than a decade—was becoming, like John Henry or Lizzie Borden or JFK, a part of American folklore.

The Bosnians had seen the same woman, but they remembered her not as a myth but as a friend. And they saw her at her best, because in Sarajevo she was doing what she had always dreamed of doing. She had always believed that art was worth dying for. As a teenager, she and a friend played a game: “How many more years of life for Stravinsky would justify our dying now, on the spot?” They finally decided that they would lay down their “paltry California-high-school students’ lives” in order to give Stravinsky another four years. “Either one of us was prepared right then and there to die.”

The New York literary world offered little scope for such heroics. But her friends in Bosnia knew that Sontag’s commitment was not a pose. They knew how easily she could have been killed.

*

Sontag was hardly the first visitor to fall under Sarajevo’s spell. In Bosnian Chronicle, a bright young assistant arrives at the French consulate in Travnik: “After only three weeks he informed Daville of his intention to write a book about Bosnia.” The Bosnians have jokes about these literary tourists. For example:

Two journalists run into each other in a Sarajevo street.

“When did you get here?” the first one says.

“Yesterday.”

“When are you leaving?”

“Tomorrow.”

“What are you doing today?”

“Writing a book.”

“What’s it called?”

“Sarajevo: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow.”

During my first visit, I was prepared to be educated—prepared, as you are when you venture to famously awful places, to be shocked. But I wasn’t prepared to fall in love. Bosnia has the magnetism of a place where the world is coming together, and also coming apart. It is to history what Iceland or Yosemite are to geology: places where the world is made and unmade. I know three places like this. One is Haiti, another is Israel–Palestine, and Bosnia is the third. These are the impossible places, the unsolvable places, the places that exist outside of ideas of progress—though they also attract missionaries: someone is always trying to save them. They are maddening, but they are also the most sheerly interesting places, where life feels more intense than anywhere else.

On my first morning of this second visit, I walked down the quays of the River Miljacka. There are few places where the story of Europe’s clashing empires unfolds as eloquently. The city of Sarajevo is not ancient; it was founded around the time of the discovery of America, on a hill beside the river. The houses of the Ottoman settlement climb at slightly different angles in order to expose them to light, giving the whole the layered appearance of a grand mosque, rising in dome after dome.

Advertisement

This is not the geometric architecture at the base of the hill, the town hall, Vijećnica. The dominant decorative note of this building is Moorish, inspired by the architecture of Spain and North Africa, different from the humbler Muslim building of Bosnia. And though it contains nods to the traditions of the local peoples—Serbs, Croats, Muslims, and Jews—it is a creation that dates to the nineteenth century, when Austria conquered a province that did not want to be conquered by Austria. Rebecca West, the greatest of Balkan literary travelers and a hater of all things Austrian, said the result was “stuffed with beer and sausages.” It was from this building, on June 28, 1914, that Franz Ferdinand departed for his appointment with the assassin Gavrilo Princip. “So was your life, and my life, mortally wounded,” West wrote.

The last time I came, it was closed, an empty shell, like so many buildings in this city. Sontag had witnessed that destruction, too: in 1993, Annie Leibovitz photographed her sitting in the library’s shattered ruins. But now, on this, my second visit, it was open, smelling of fresh paint. There was a plaque by the entrance: “On this place Serbian criminals in the night of 25th–26th August, 1992 set on fire National and University’s Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina Over 2 millions of books, periodicals and documents vanished in the flame.” Here was another articulation of the ideal for which Sontag had always been willing to die: to keep books from being burned.

Today, the building has been restored, but it is still mostly empty, awaiting a new purpose. Its fresh restoration brings out the ideology behind the architecture: here is a symbol of one ethnicity, there a typical craft of another, and on the terrazzo floor is a starry monogram honoring the four peoples of Bosnia. It is a strangely politically correct note in a monument built by a foreign conqueror; an imperial crown, or the heraldic arms of the monarchy, might have been more straightforward. But something in the world had shifted. No matter how hypocritically, some ideal had to be honored: an ideal of cosmopolitanism, of a benevolent coming-together of peoples. It must have been felt that old-fashioned invasion, the law of the strongest, which for most of history had been reasons enough, would no longer do.

*

The ideal of the free society can be abused—as it was by an empire that pretended to celebrate the same peoples it was enslaving—yet this ideal (of a city where the mosques and the synagogues and the churches stand peacefully side-by-side; of the freedom to visit the library or put on a play) has outlasted its most hypocritical advocates. The ideal is too powerful to be destroyed. But there are other forces, powerful too, arrayed against it. It persists, but nothing guarantees its triumph.

There are, after all, other options, including some that fall short of outright racial murder. One was the stagnation pressed on Bosnia twenty-five years ago. The Dayton Accords stopped the killing, but created two federal entities, the Republika Srpska, for the Serbs, and the Federation, for the Muslims and Croats. Each group shares in a three-man presidency, a recipe for dysfunction. Every position has become a patronage opportunity, and people applying for most government jobs are consistently forced to identify themselves by the labels Croat, Serb, or Bosniak. Under this regime, Bosnia has become one of those aid-state basket cases where everything is waiting for a green light from this embassy or that.

A few days before the US presidential election, the tension here was palpable. “In some ways, we depend on who’s in the White House even more than you do. America goes on, but for us everything depends on this: my work, my income, my safety,” said a friend whose organization is largely funded by Americans. “And we don’t have a say.”

Bosnians still depended on the whims of a distant empire. No regime change in Washington, though, can answer the more fundamental question of what to do about this place. For the first time, I understood why monarchy might have been a solution. In another age, it might have made sense to ship in some second son of the Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburgs who looked good on a horse. There is, in fact, a viceroy-like figure in Sarajevo, the High Representative, appointed by the European Union and the United States. But few people in the European Union or the United States care about this semicolonial protectorate, so Bosnia presents a sad paradox: abandoned, but not quite independent.

Inside Bosnia, the post-Dayton local politicians—sectarian by definition—have every interest in stoking old divisions. They have been remarkably successful in this, if in nothing else. The Serb population of Sarajevo proper, that once-proud symbol of multiculturalism, today comprises less than 4 percent. The city’s suburb of Istočno Sarajevo, East Sarajevo, has about the same percentage of Muslims and Croats. Its inhabitants call the central city Bliskoistočno Sarajevo, “Near East Sarajevo,” an unfunny joke that refers to the downtown’s predominantly Muslim population. Old allegiances persist. “They would rather die than admit they were wrong,” a friend says of his fellow Bosnian Serbs.

The tenaciousness of the hatred is all the stranger because war and division have benefited nobody. Bosnia today is poorer and more isolated than ever, and, virus or no virus, its young people leave. Can you blame them? Vienna and Milan, after all, are still only an hour away. More than 200,000 young Bosnians went abroad between the end of the war in 1995 and 2018. In the Brain Drain category of the World Economic Forum’s 2017–2018 database, Bosnia ranked 135th out of 137 countries.

*

The country feels as unassimilable as ever. Old solutions have come and gone. But the ideal persists.

On the second night I was there, the Bookstan Festival opened in Pozorišni Trg Susan Sontag. The festival’s motto—No East, No West—affirmed fidelity to the ideal, and so did the people who came to the square. The chairs were far apart and the virus protocols were maintained, but the audience was mixed—Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, Jews—and as the sun set over the still-crumbling buildings, we invoked the woman for whom the square is named.

We invoked her childhood in middle America, how she grew up in the utter absence of role models for intellectual girls, and how she made herself a model for generations to come. We invoked her love for Thomas Mann, whom she met in his Californian exile, and whose steadfast adherence to the highest traditions of his culture remained forever after an aspiration of hers. We invoked the extreme reactions she provoked in the United States and explained how it was possible that some saw her as a figure of liberation and others as a figure of decadence. We invoked her actions in the nearby theater, and how, with the simple act of putting on a play, she had placed herself in the succession of all those who risked their lives for an ideal of human dignity.

Over the last year, as I toured my book from Rio to Utrecht to Dallas to Jaipur, I had talked about these themes a thousand times. Yet they felt different in Sarajevo. This was partly because we were in the place that was dearest to Sontag, partly because we were in a square that bore her name, and partly because many of the people there had known her. As the evening went on, I began to feel that we were evoking something more than život i djelo, the Bosnian subtitle of my book, life and work. Nearly three decades on, the particulars of her sojourns in Sarajevo had started to fade. It was no longer so important that she had brought a friend some perfume or given a little girl half a watermelon for her birthday.

In celebrating Sontag we were evoking the ideal of the free society itself, of individual dignity—and recommitting ourselves to it, despite everything. I realized that Sarajevo is so stirring because it is a place of despites. Despite the war. Despite the divisions. Despite emigration and poverty and pandemic, we came together to honor that ideal. If it can be taken for granted in luckier places, it’s not taken for granted here—and this was what makes Bosnia so alluring. It never seems easy here; it hardly even seems possible. And for precisely that reason, Bosnia is where the ideal seems most alive.

*

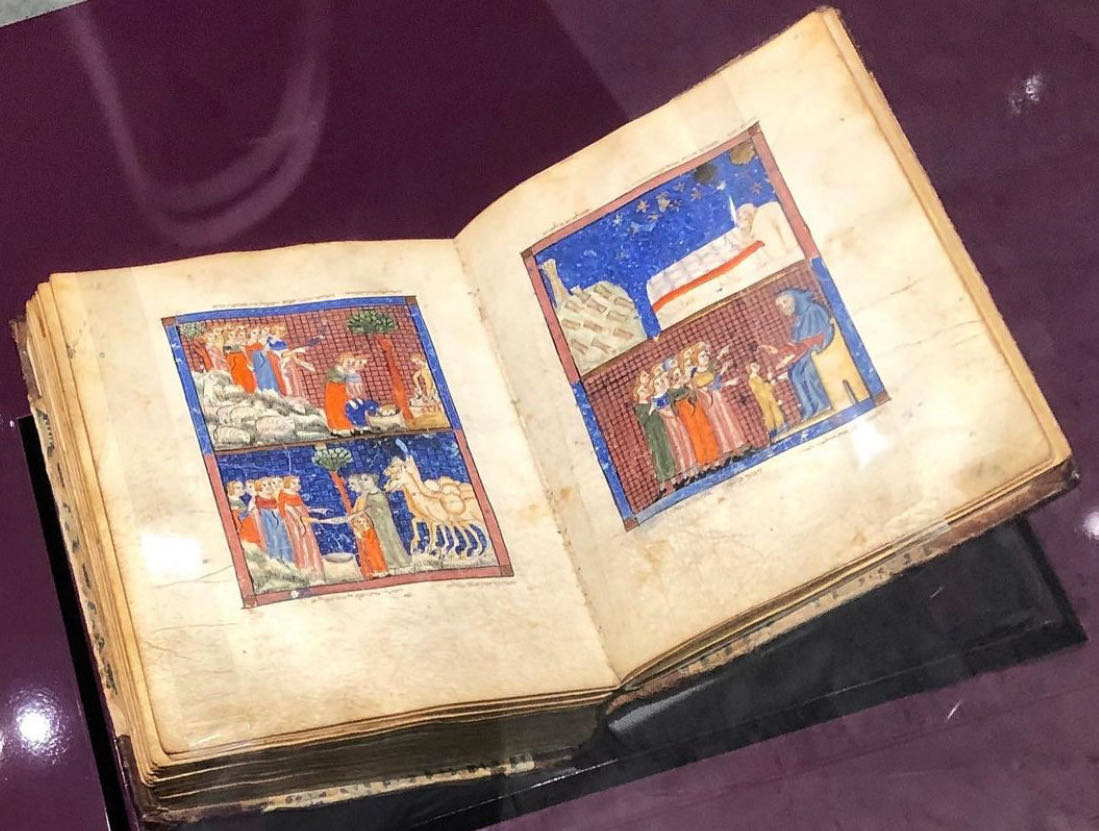

The next day, I went to see the Sarajevo Haggadah, the unrivaled jewel of the Bosnian collections. Created in Catalonia, perhaps in Barcelona, in the fourteenth century, this mysterious manuscript survived centuries of calamities. It escaped the Spanish persecutions and the expulsion of the Jews by Ferdinand and Isabella. It made it to Venice in the sixteenth century and then reappeared at the end of the nineteenth century in Sarajevo, where it was sold by a destitute Jew to the National Museum. During the Nazi occupation, it was hidden by its Muslim curator in a village mosque, and then, nearly half a century later, with the Serb artillery perched just above the museum, it disappeared. There were rumors it had been sold or stolen or destroyed, but it had been whisked away to a bank vault and hidden one more time.

The last time I was here, my wish to see it was foiled: the museum, victim of yet another interethnic squabble, was closed. Now it was open but empty, because of the virus. “Bosnians call to ask when we’re reopening,” the director told me. “I tell them we’re open. But nobody comes.” We walked through the darkened galleries, stuffed with spectacular Roman remains that reminded me how close we were to the Mediterranean, and headed to the safe room that holds the book. The director flipped on the lights, and suddenly there it was.

It is little bigger than a modern hardcover, and it was opened to the story of Joseph. The neat calligraphy is still perfectly legible: va-yachalom yosef ha’shemesh ve’ha’yareach va’echat eser kochavim… “and Joseph dreamt of the sun and the moon and eleven stars.” Beneath a sky of gold and lapis lazuli, a child dreams of eleven stars and eleven sheaves of wheat, symbols of him and his ten brothers. In the next miniature, just below, he recounts his dreams:

For, behold, we were binding sheaves in the field, and, lo, my sheaf arose, and also stood upright; and, behold, your sheaves stood round about, and made obeisance to my sheaf. And his brethren said to him, Shalt thou indeed reign over us? or shalt thou indeed have dominion over us? And they hated him yet the more for his dreams, and for his words.

The next paintings show the brothers’ revenge: they cast him into a cistern, slaughter a young goat on his tunic to convince their father that he is dead, then sell the boy into slavery. But despite his tribulations—despite being younger, smaller, powerless, and hated—Joseph’s is a story of triumph. He rises from Egyptian slavery to become Pharaoh’s most trusted counselor; he eventually is reconciled with his brothers, lives to see his great-grandchildren, and dies, a great patriarch, at one hundred and ten—still true to his ideal.

To see this story, in this book, in this city, is to feel a resonance it would not have elsewhere. Joseph had survived, and so had the Haggadah, and so, despite everything, has the idea of Sarajevo. The empires come, the empires go, but the book glows in the ambient gloom, an urge to recommit—morally, socially, politically—to something that rises above our individual lives.