“This country has no tradition of its own,” Argentina’s master writer, Jorge Luis Borges, told me in an interview in 1975. “There’s no native tradition of any kind since the Indians here were mere barbarians. We have to fall back on the European tradition, why not? It’s a very fine tradition.” The words grate to modern ears, but they seemed true to Borges’s world. His own grandmother, Frances Anne Haslam, had come from Staffordshire, England. And by 1920, when Borges turned twenty-one, over half the population of his native Buenos Aires had been born in Europe, the result of a vast wave of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century immigration.

According to this idea of Argentina’s roots, our capital city of Buenos Aires is “the Paris of South America,” and “we are all descendants from Europe,” as then President Mauricio Macri said at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in 2018. A corollary of this claim is one made by an earlier president, Carlos Menem, to a Dutch audience at Maastricht University in 1993 that, because Argentina had abolished slavery as early as 1813, “we don’t have blacks.” At a later lecture—bizarrely enough, at Howard University in Washington, D.C.—Menem added, “that is a Brazilian problem.”

For me, the myth of a European-only Argentina reached its breaking point last November, with the death of the soccer star Diego Maradona, arguably the greatest player who ever lived. He transcended the world of sports to become a figure of hope and defiance for millions of Argentines.

“For the kind of people I identify with, people working their way up from the bottom, the kind of kids who play ball barefoot in the street, Maradona was the Malcolm X of those people,” the artist Emiliano Paolini told me. The comparison at first surprised me, but then I reflected that in Argentina, the word “negro” (“black,” in Spanish) is commonly used as a nickname for anyone with a slightly darker skin tone. It can be affectionate, but it can also be a term of abuse for a low-class person—one often used by anti-Peronists to dismiss their working-class opponents.

Maradona, who came from a poor family of mixed indigenous Guaraní and Italian heritage, was definitely “negro” in that specialized Argentine sense. But for those who lived in the shantytowns outside Buenos Aires, where he grew up, Maradona was a working-class hero. To his fans, his impudent virtuosity on the field was a way of thumbing his nose at authority and privilege.

As “white” as its national soccer team generally appears to be, Argentina was never as monotone as many of my countrymen like to imagine. Its black and indigenous inheritance is on open view for anyone with eyes to see; and the farther back you go into Argentina’s past, the fewer Europeans you find.

In 1778, when the Spanish carried out their first census of the Viceroyalty of the River Plate, Africans accounted for 37 percent of its 421,000 people. In some provinces, blacks made up more than half the population. Just as its indigenous heritage was made to vanish from the record, though, Argentina’s history of black enslavement has also been erased. According to official legend, the 6.6 million European immigrants who disembarked at the port of Buenos Aires between 1857 and 1940 were greeted by the empty Pampas.

For much of the country’s modern history, that fallacy has proved hard to contradict, partly because Argentina had no dominant pre-Columbian civilization comparable with Mexico’s Aztecs or Peru’s Incas, or a phenotypically discernible black population like Brazil’s, to present as counterargument. From what or whom do the Argentines descend, then? “From the ships” remains the ubiquitous reply, meaning the ships that sailed from Europe in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, not those that sailed from Africa with cargos of slaves over the prior three hundred years.

The erasure of Argentina’s black history was accomplished by a deliberate nineteenth-century policy for the whitening of Argentina, upon which a national identity of whiteness has been grafted. Erika Edwards, an associate professor at University of North Carolina at Charlotte, was dumbfounded on her first trip to Argentina in 2002. “I did not see another black person at all. I was, like, What is this? What’s going on? It was three and a half weeks before I finally saw a black person on the street. We eventually could communicate enough to know that she was from Brazil.” But Edwards would soon discover that Argentina had not always been so white. In fact, the opposite. “What really shocked me was: What happened?” Edwards told me. “Where are they? Where are these people in Argentina who should be looking like me?”

Advertisement

It was a question Edwards repeatedly asked the Argentines she met. “The most common answer I would get was: ‘There are no blacks. They disappeared.’ What? How did they disappear? ‘Las guerras [the wars] killed them all.’ Others said they all died in the yellow fever epidemics of the nineteenth century. The best one, I think, was: ‘They didn’t like it here so they moved to Uruguay, because there’re still some over there.’ I would get all these myths that, at the time, I thought were hilarious, but I didn’t realize that for some people it was their truth.”

Determined to explore the question, Edwards returned frequently to Argentina over the next eighteen years, resulting in a fascinating book, Hiding in Plain Sight: Black Women, the Law, and the Making of a White Argentine Republic, published last year by University of Alabama Press. In it, Edwards writes:

Over time, I made two observations from this short and popular response. First, the phrase “there are no blacks” perpetuated the national narrative of Argentine exceptionalism. Many Latin American countries acknowledge their ethnic diversity, often touting a national narrative of “mestizaje” (mixed identity). Argentina did not fit that model. Instead the image of Argentina remains an exception because of European immigration, which made it a white rather than a mixed country. Second, the answer “they disappeared” suggested that what happened to the black population remained a mystery. If blacks disappeared, then they had previously existed. Based on these observations, a black population does not fit Argentina’s national image.

Reading Edwards’s book and later interviewing her, I felt an uncanny sense of familiarity with her experience. On my own arrival in Argentina in the 1970s, having been born and raised in Washington, D.C., I found myself asking the same question—where are the Afro-Argentines?—only to receive the same answers: “They were killed in the wars of independence.” “There were never many to start with.” In some cases, these answers came from people who clearly had some black ancestry themselves. When I asked about that, my question seemed to provoke discomfort and, often, the rote response, “It’s not black, it’s southern Italian.”

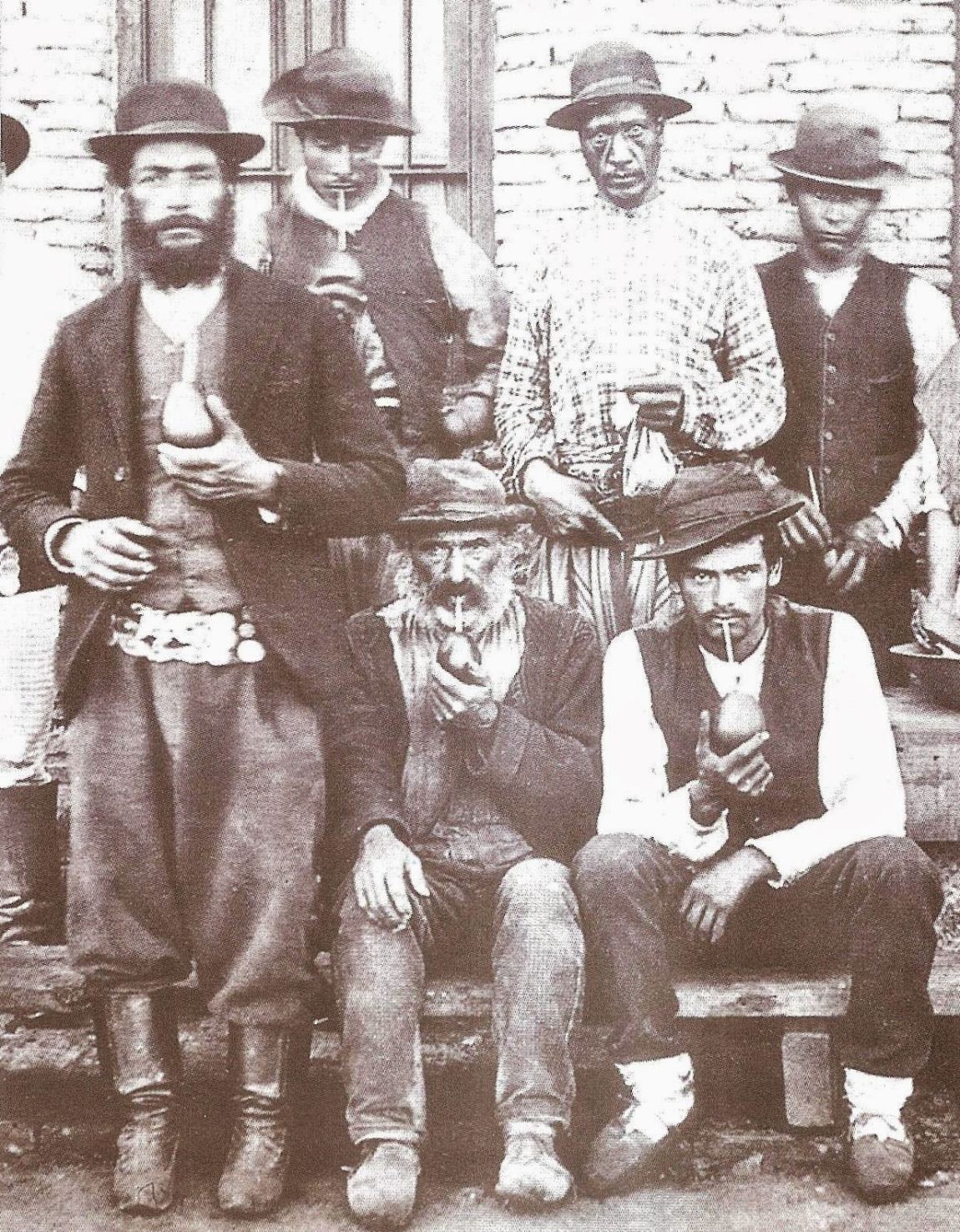

But as Edwards’s book title suggests, Argentina’s black history survives to a large extent in the physical characteristics of many living Argentines; it’s just most people have been trained, or are invested, in not seeing it. Other foreign visitors, long before me or Edwards, noticed this. Their impressions were recorded in George Reid Andrews’s groundbreaking 1980 book The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires. Andrews quotes Alexander Gillespie, a British soldier captured by Argentine forces during the failed British invasion of Buenos Aires, who noted of the city’s population in 1807: “A fifth were white, the rest being a caste composed of various states of mixture and progressive alteration, from the black man to the blondest European. Though color may improve, even in the most refined cases there persists a trace of the features that recall the true origin of many of them.” Another British visitor, Samuel Haigh, wrote in 1827: “Pure whites are not numerous, and the most common is a caste of white, Indian and black, so mixed that it would be difficult to fix its members’ true origins.”

“They [non-white Argentines] didn’t go anywhere,” Edwards told me. “There’s a major whitewashing that does happen because of this huge immigration at the end of the nineteenth century, but it’s a concerted effort from the state to reimagine a country that is raceless and thus blackless, without blacks, without Indians, without anyone who does not fit into a European descendancy. It definitely engulfs a lot of people, what we scholars call this notion of invisibility.” This is how, Edwards explained, a pervasive willful ignorance has become entrenched in the country—a view that black heritage and history just doesn’t exist, when clearly it does.

*

Argentina’s obsession with whiteness is practically unparalleled in Spanish America; other former Spanish colonies have proved far better at accepting their mixed inheritance. Spain’s two major dominions, Mexico and Peru, take some pride in their indigenous roots and have made them a cornerstone of their national identities. Argentina’s close neighbor Uruguay, the only Latin American country with a higher percentage of whites than Argentina, celebrates the existence of its vibrant black community. “I don’t like going to Argentina because I feel really uncomfortable there,” a black woman in Uruguay recently told me.

This is not to minimize the way minority white elites across Spanish America often inhabit a different reality, self-segregated from indigenous and black peoples. In Chile, which shares a lengthy border along the high Andes mountain range with Argentina, people of mixed race are likely to self-identify as white, although Chile has a more varied racial composition than Argentina because of the smaller proportion of Europeans who migrated there.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Argentina likes to parade its immigration-friendly credentials—“Only the United States received more immigrants,” you often hear—but the claim elides an ethnocentric denial of significant indigenous presence. According to British journalist Robert Cox, Argentines used to boast about being “the only white country in Latin America.” When he arrived in Argentina, in 1959, to work at the English-language Buenos Aires Herald, he said, “They made jokes about the ‘Tropicals’ and ‘Monkeys’ in Brazil.”

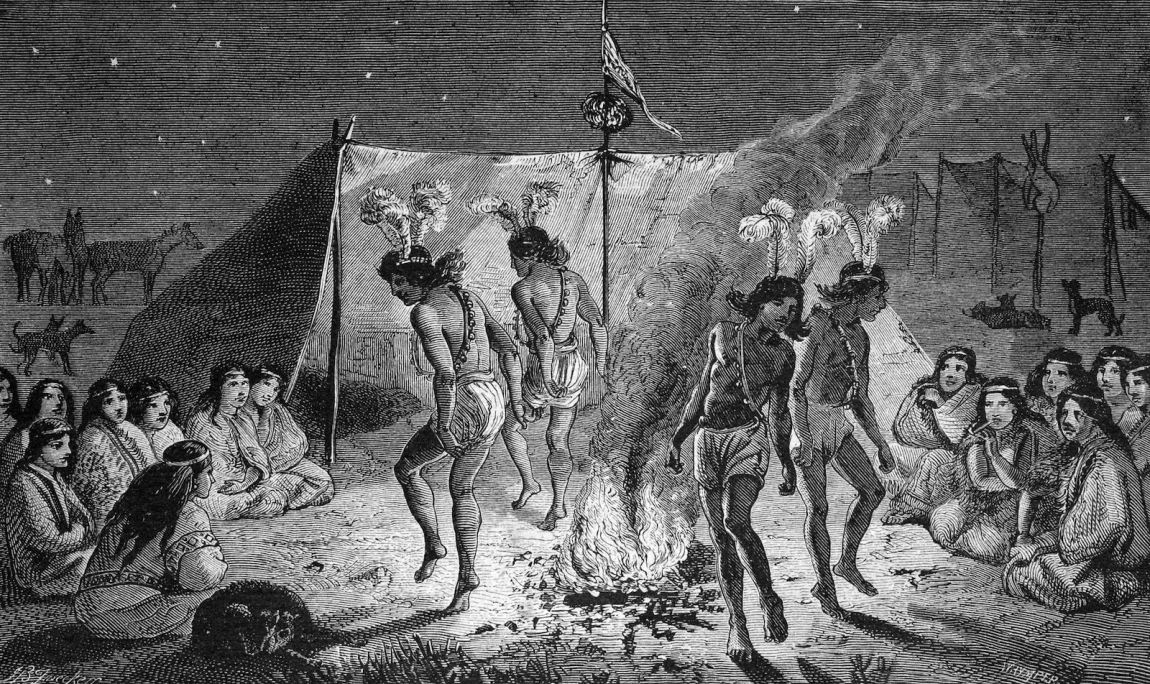

Although they did not find imposing cities such as Tenochtitlan or Cusco, the Spanish did find numerous peoples living in what is now Argentina, when they arrived in the mid-sixteenth century. The Diaguita, who held a large domain in what is now northwestern Argentina, practiced agriculture, bred llamas, and were master potters and engineers who built canals. They resisted the conquistadors until 1667—more than a century longer than the Aztecs or Incas did. That year some two thousand members of the Diaguita’s Quilmes tribe, the last to fall, who had inhabited a stone-built city for more than a millennium, were force-marched over nine hundred miles to what is now a district outside Buenos Aires. The region still bears their name—though the people were declared extinct by the new Argentine revolutionary regime that heralded independence in 1816.

Two decades after independence, following a long period of bloody civil war between landowner warlords with large private armies of blacks and criollos at their command, a group of intellectuals and politicians known as the “Generation of 1837” crafted the European-only “white Argentina” myth when they sat down to frame the republic’s first constitution in 1853 as a deliberate policy to unify the nation.

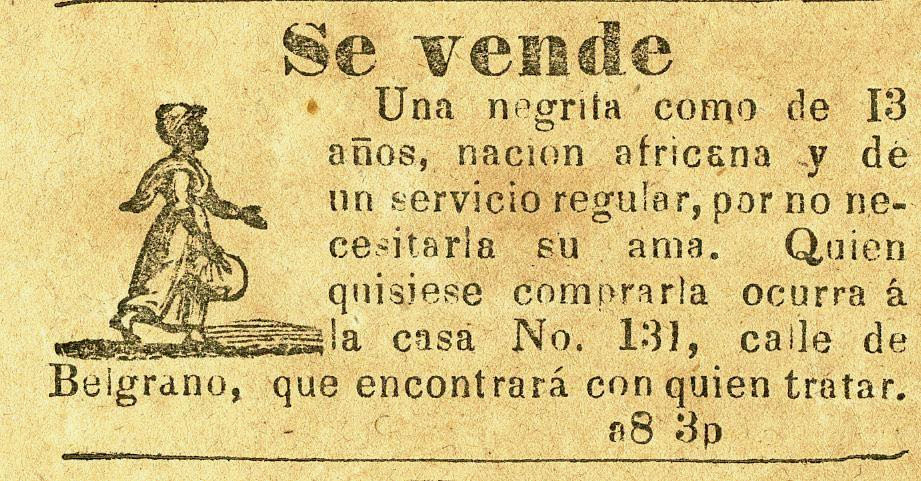

The formal abolition of slavery in that constitution, which took effect nationwide in 1861, came so late that slavery was by then almost nonexistent, as its drafters well knew. To this day, Argentines take pride in an earlier anti-slavery decision, the Free Womb Act of 1813, which ostensibly manumitted the children of enslaved people. But slave owners quickly found imaginative ways to skirt the law. Some took their pregnant slaves to give birth in Brazil, where slavery was not abolished until 1888, returning with those babies as imported slaves. Through this subterfuge and others, slaves continued to be offered for sale in Buenos Aires newspapers well into the 1830s.

Argentina’s 1853 constitution was based on a book published the previous year by Juan Bautista Alberdi, an Argentine-born liberal political thinker aligned with the 1837 Generation. Alberdi’s book, Bases and Starting Points for the Political Organization of the Argentine Republic, was published in Chile, where the thinker had fled into exile from persecution in his homeland. Its central theme revolves around the dictum “Gobernar es poblar” (to govern is to populate), which became the leading principle of the new republic.

It was a maxim that I, growing up first in Washington, D.C., and then in Dublin as the son of an Argentine diplomat, heard repeatedly from the stream of Argentine nationals who passed through our home. Having lived in Argentina only from ages seven to nine, I knew little of my country’s complicated history. To my outsider’s ear, the mantra sounded portentous and faintly Orwellian, yet seemed meaningless.

It was only years after settling in Argentina in 1975, and rereading Alberdi’s book, that I fathomed its true intent. When Alberdi said “populate,” he meant populate with Europeans—as specified in the 1853 constitution’s twenty-fifth article (and retained in the amended 1994 version), which states that the Argentine government “will promote European immigration.” And it was Alberdi who provided the rationale:

The savage is defeated, in America he has neither dominion nor lordship. We, Europeans by race and civilization, are the masters of America…Were it not for Europe, today America would be worshiping the sun, the trees, the beasts, burning men in sacrifice, and would not know marriage. The hand of Europe planted the cross of Jesus Christ in former Gentile America. At least, if only for this, blessed be the hand of Europe!…Who knows a gentleman among us who would boast of being fully Indian? Who would marry his sister or daughter to a nobleman from Araucania [the general term he used for Argentina’s indigenous people] and not a thousand times to an English shoemaker?…Do you think that an Araucanian is incapable of learning to read and write Spanish? And do you think that just by doing so he stops being a savage?

And so forth. Alberdi’s vaunted liberalism operated within an exceedingly narrow range of European primacy. He believed in religious freedom, but only for British and other northern European immigrants to practice their Christian faiths in Catholic Argentina; he deprecated the religious beliefs of Argentina’s original inhabitants. Alberdi believed in an immigrant melting pot, but only one of white Europeans. In a later edition of his book, he added this rider to his maxim: “To populate is not to civilize, but to brutalize, when populating with Chinese and Indians from Asia and blacks from Africa.” Today, there is hardly a town in Argentina without a street named after Alberdi.

Back in the mid-1970s, when I was a cub reporter on the Buenos Aires Herald, and the country was sliding toward the bloody rule of a military dictatorship, I had skipped impatiently through these racist slurs to get to the pages I needed for comfort—the sections Alberdi wrote that seemed to underpin Argentina’s disappearing liberal democracy. Unwittingly, I, too, had bought into the European-only myth—the very same that Borges gave voice to when we spoke back then.

*

Ten years ago, Nicolás Parodi was a thirty-year-old Buenos Aires news photographer who moonlighted by taking pictures at rock concerts. One of the musicians he followed was Carlos García López, a famous Argentine blues guitarist who was giving a concert at the African Diaspora in Argentina Association (DIAFAR), an organization dedicated to raising awareness of Argentina’s black heritage. Parodi approached the association for permission to photograph the event. “No sooner did I walk in than they started telling me I was black,” Parodi says. “I was like, What? How? Of course, I’m not black, I’m just dark.” It took Parodi a long time to understand that his blackness had been invisible even to himself.

“I had lived all my life as ‘El Negro,’ the nickname my friends called me, but I had never thought I could be an Afro-descendant…I knew nothing about black culture or black history. Over time, I slowly began to recognize, in the music that I liked, in my skin tone, that everything I did was related to a certain black aesthetic.”

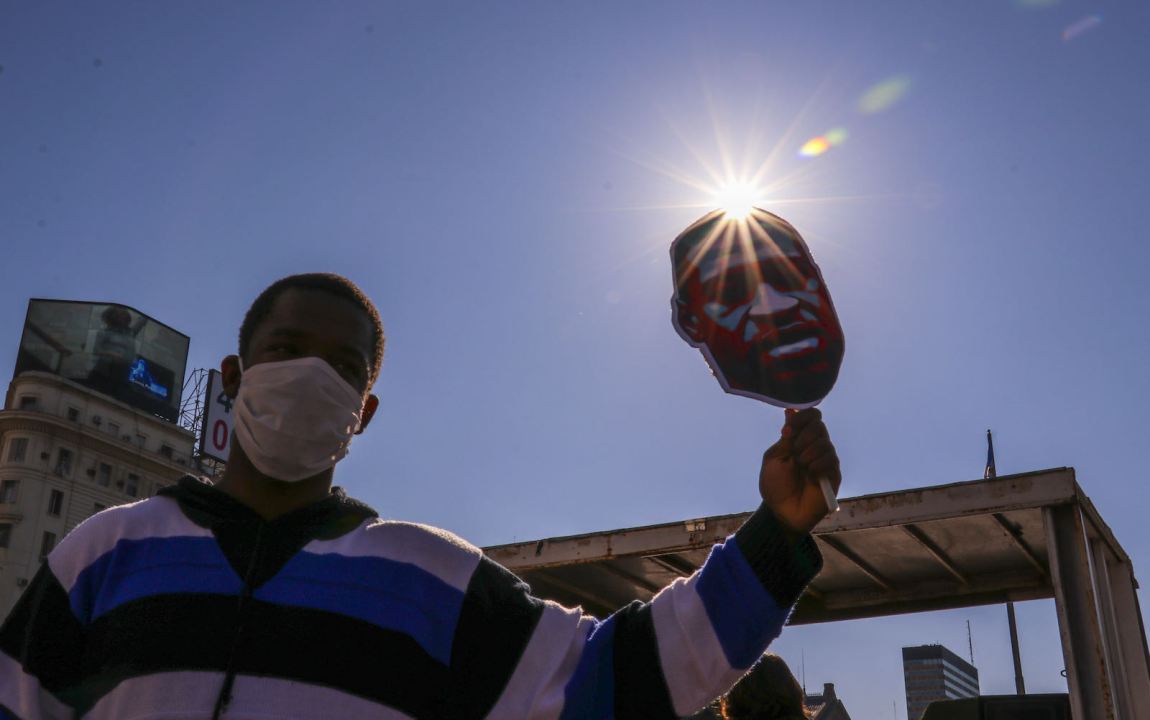

Being an adopted child, Parodi remains ignorant of his biological family’s history, but in other ways his predicament is hardly unique. Although only half of 1 percent of Argentinians self-identified as Afro-descendants in Argentina’s last 2010 census, the real number is believed to be much higher, around 5 percent, according to DIAFAR and more recent government studies. “At DIAFAR, we joke that everybody has a black grandparent hidden in the closet,” says Parodi, who became a leading member of the association.

“It’s difficult if you’ve spent your whole life denying the notion of blackness,” he explains. “There’s no moment at school or university where our black heritage or racism is discussed. There’s so much denial, so much invisibility, that it’s not taken into account.”

People of mixed race often pass as white in Argentina, and it helps to have been economically successful. Indeed, they may themselves be unconscious of their black heritage: the deliberate whitening policies of the nineteenth century forced many black people, especially black women, to “pass” as white in order to marry Spanish colonists or European immigrants. Today, the memory of that practice has frequently been lost even to their own descendants.

“You either are considered to be part of this national imagery of whiteness, or if you don’t fall into that description or characterization, then you are considered to be something else,” says Edwards. “Some people that probably knew they were black went underground about it, kind of kept quiet, kept to themselves. They weren’t going to try and rock this larger boat. Keep your family safe, keep moving. So after a generation or two of ‘miscegenation,’ you just don’t talk about the fact that your grandma was black, and by the third or fourth generation, they don’t even remember her.”

A 2008 study conducted by researchers at the University of Brasilia found that, on average, the genetic makeup of current-day Argentines was 9 percent of African ancestry, alongside 31 percent Amerindian and 60 percent European. A majority of nonwhite genetic markers were inherited down the maternal line. “The preferential occurrence of mating between European men and Amerindian and African women is evident,” the study states. Other genetic studies have found fewer African markers, around 4 percent, but with the same overwhelming sex bias involving black women and white European men. (Historians stress two main factors behind this sex bias. First, the majority of European settlers were male; second, a large number of Argentina’s black men died as the result of the harsh conditions of enslavement and being pressed into military service in the country’s nineteenth-century wars.)

These genetic research projects, a growing awareness among many Argentines of the black roots in their own families, together with the work of a new generation of Argentine academics intent on dispelling the myth of an exclusively white Argentina, have increasingly brought my country’s black heritage into public discussion. In 2013, November 8 was officially designated the Day of Afro Culture. Argentina’s ministry of culture stated that the idea “that the country was forged by white European immigrants is a myth that is slowly being demolished,” and last November a government Commission for the Historic Recognition of the Afro-Argentine Community was created. In doing so, the government acknowledged that “the Afro-Argentine community, made up of more than 2 million people who are descendants of Africans brought as slave labor to what is now Argentina, has historically been invisible, denied and deemed foreign as a result of the structural racism that operates in our country.”

Parodi is proud of a music video made by Afro-descendant Argentine artists to publicize the work DIAFAR does. It features a guitar solo by García López, a musician with whom I became friendly in the 1990s, who also went by the nickname “El Negro.” Sadly, he died in a car accident in 2014, but I remember going for a ride, a quarter-century ago, in the old Ford Fairlane he drove, music blaring through the windows out loud. “I’m definitely black,” he called out, full of laughter. For a moment back then, it didn’t feel as though we were in Argentina at all. Today, it might seem more possible we were.