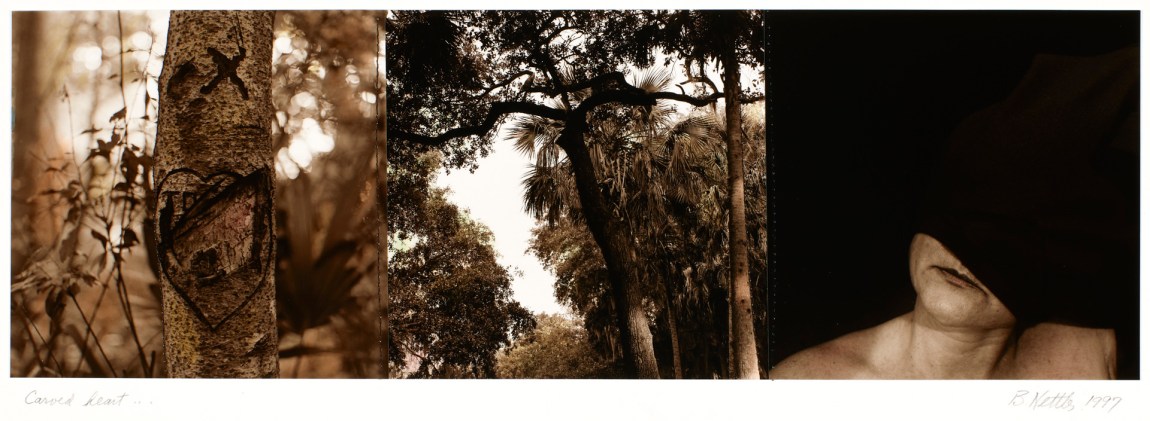

The artist Bea Nettles was born in 1946 in Gainesville, Florida, and grew up with a love of the natural world. A drawing made when she was in grade school contains, she writes in her 1979 photobook, Flamingo in the Dark, the seeds of her mature work: “plants…an exotic bird, moonlight, water, reflections, and the Florida night air”:

As children we spent most of our summers at our lake house. My resourceful father built the house in a hundred year old orange grove on the banks of Santa Fe Lake. Here we found Indian arrowheads, tadpoles, snakes, fish of all descriptions, turtles, weeds, birds, waterbugs and water lilies. The image of a rainstorm moving towards us across the lake, the smell of the orange blossoms while I lay in the shade on cool chickweed, the feel of hot sandy roads and sandspurs under my bare feet, and all the wildflowers I can no longer name are my resources.

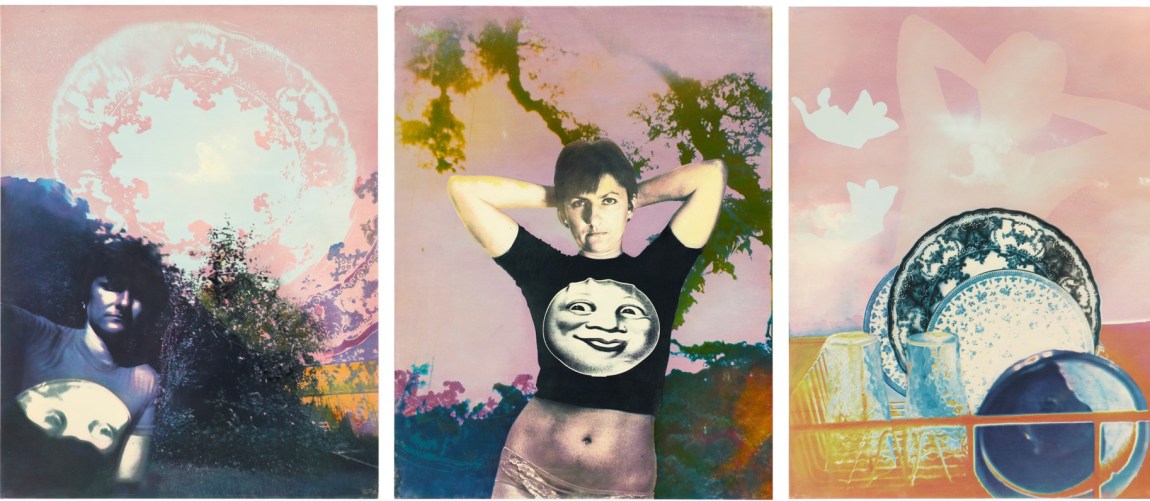

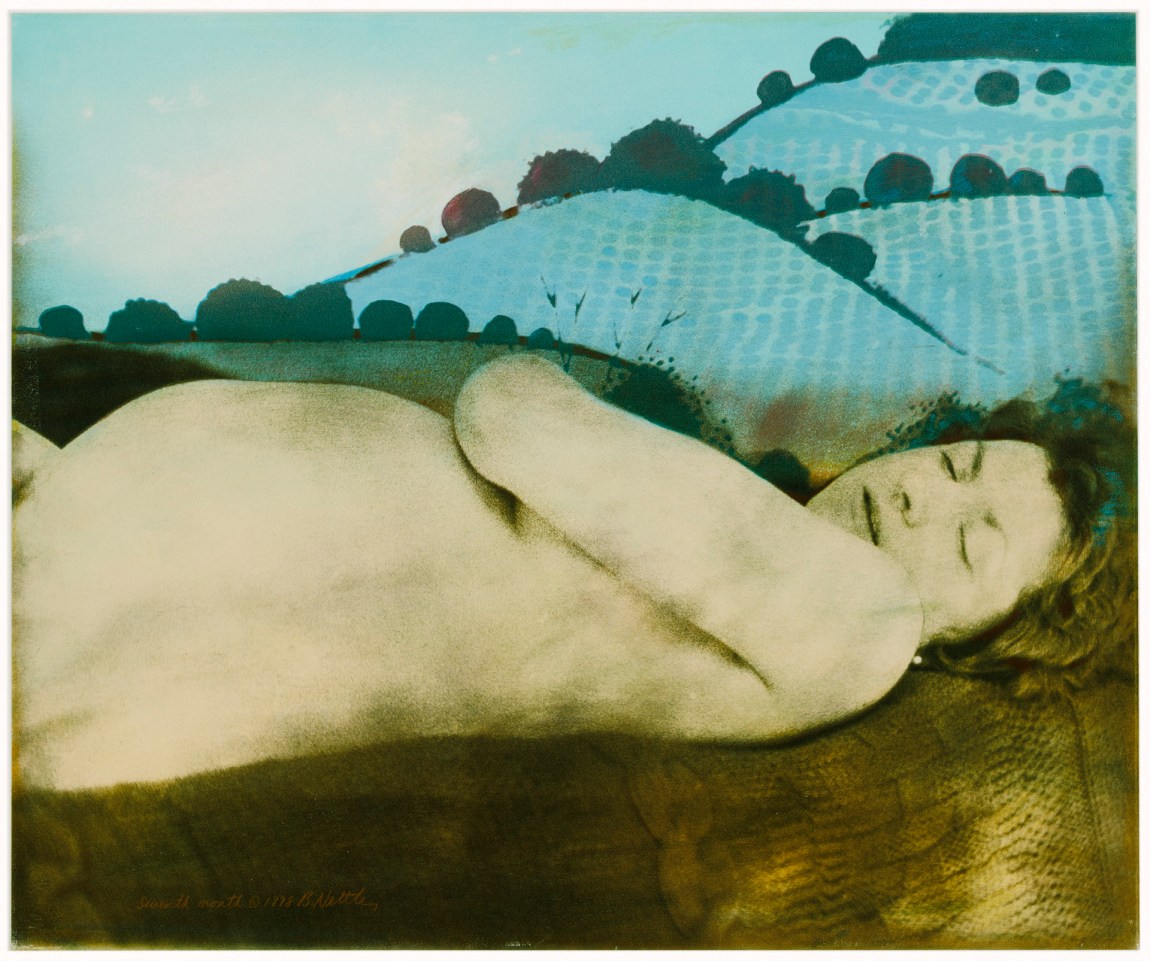

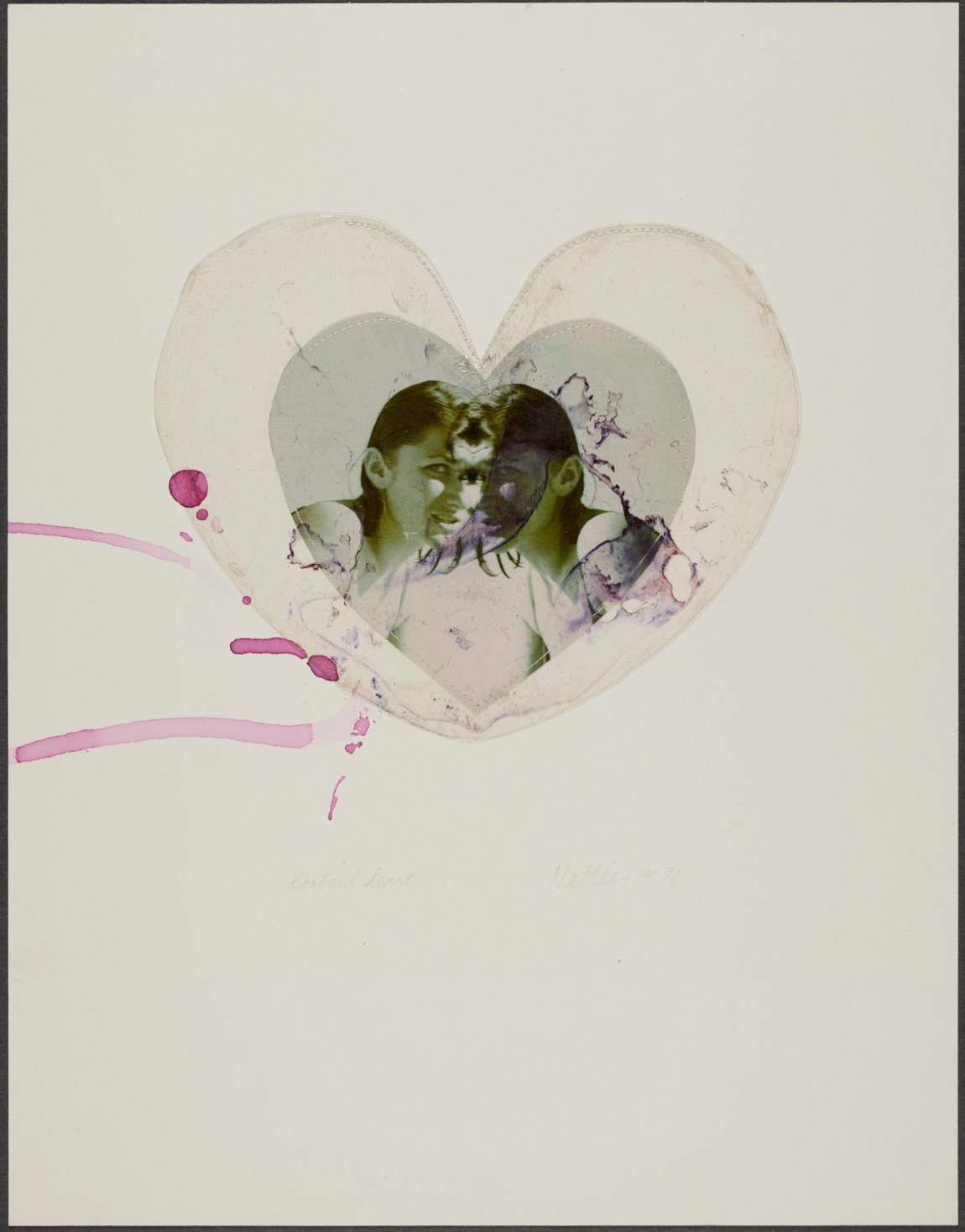

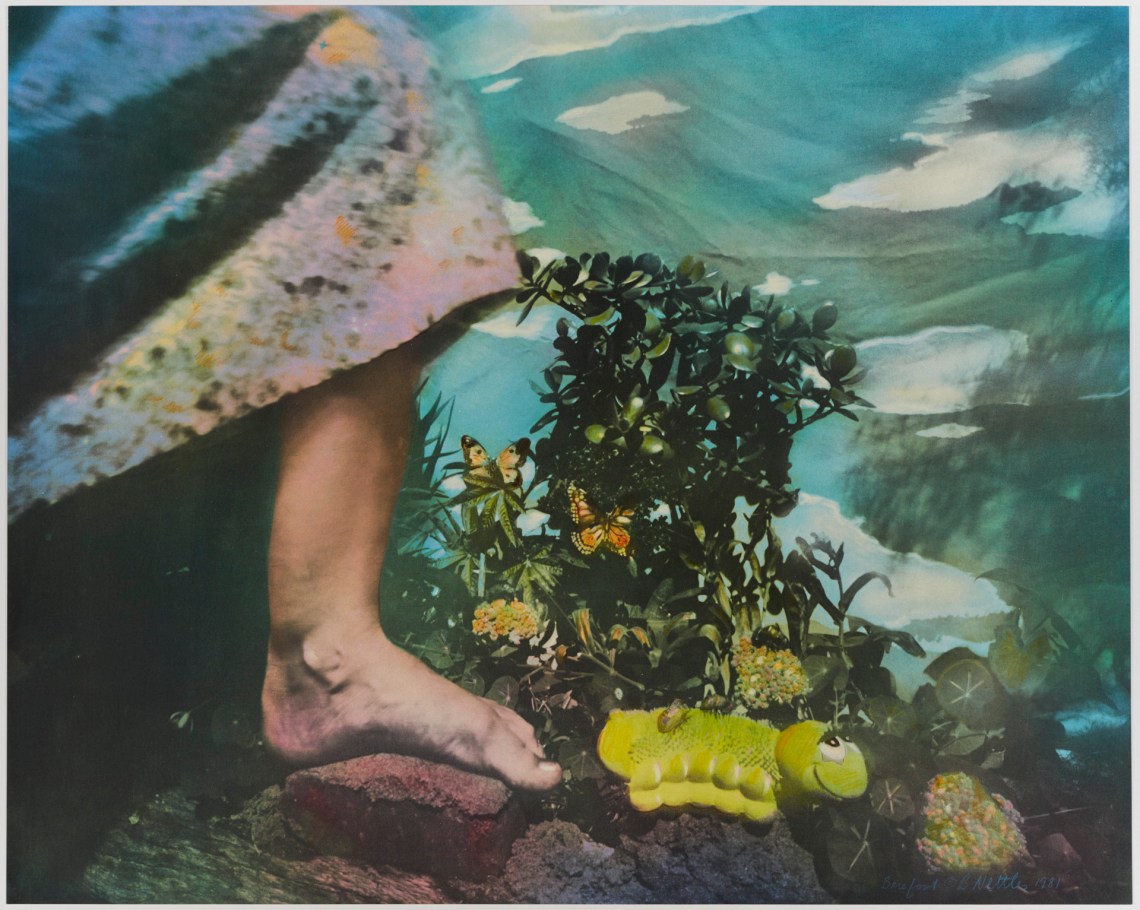

The book’s images were made between 1976 and 1979 using multilayered large contact negatives, including some that belonged to her father, and a light-sensitive, applied-color process called Kwik-Print. Blush pink, goldenrod, burnt orange, and cotton-candy blue predominate, as do rounded forms: saucers, faces, Nettles’s pregnant belly, tomatoes, hills, the moon. Nettles pieced the photobook together from memories, “starting with my girlhood in Florida and starting over again with my daughter Rachel’s first year.” The story is linear—Nettles’s life from childhood to motherhood; palimpsestic—with different photographs layered to make up a single image; and circular—from childhood back around to childhood. She has called Flamingo in the Dark a “visual autobiography,” a phrase that can be applied to all of her work.

Fifty years into an original and prolific career, Nettles is now the subject of her first major monograph, Bea Nettles: Harvest of Memory, which includes nearly three hundred images and accompanies a retrospective, curated by Olivia Lahs-Gonzales and Jamie Allen, that opened at the Sheldon Art Galleries in St. Louis, Missouri, in 2019, traveled to the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York, and is now on view at the Krannert Art Museum in Champaign, Illinois, through March 6. The difficulty in describing her work is that it is so varied—as the artist changes process, her work changes form, often in surprising ways. Primarily photography, it also combines elements of sculpture, sewing, bookmaking, and writing. The results are photographic objects that fold time and space, reflecting on memory, motherhood, nature, autobiography—giving shape to the overlap, particular to women, of domestic, public, and private worlds.

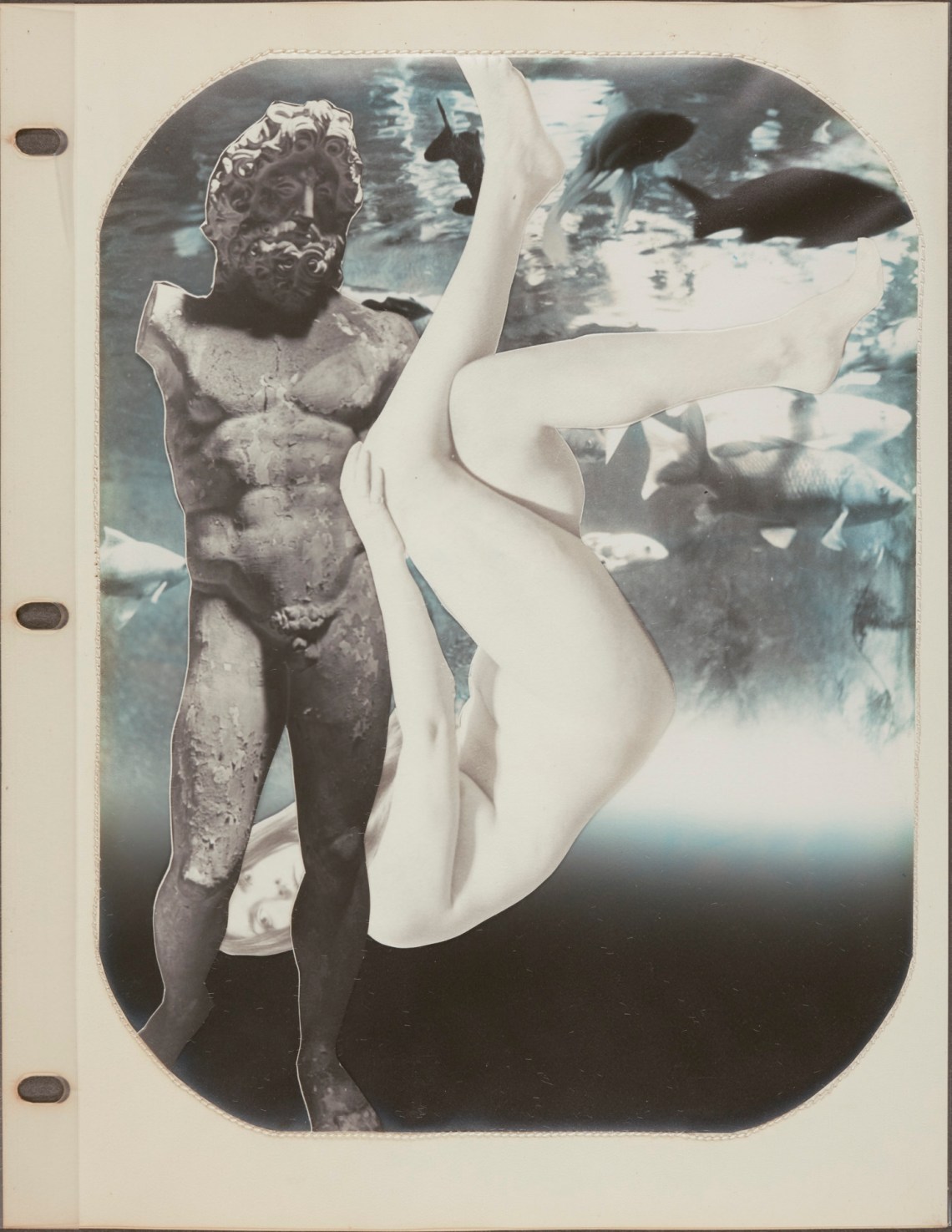

Nettles’s maternal grandmother was a primary influence—she was, Nettles said in a 2012 interview with Mary Statzer, published in Statzer’s The Photographic Object 1970 (2016), “kind of a feminist and an artist way before her time. She used to machine-sew paper together to make books for me, or make lampshades out of laced-up Clorox bottles. I saw her using all of these bizarre materials, so I knew it could be done.” Over the decades, Nettles has taken inspiration from other women in her family—she has used her sisters as models and incorporated her mother’s poetry into her books—and imagined the worlds of lake ladies and other female mythological figures, including Eve, Venus, and Nut, the Egyptian goddess of the sky.

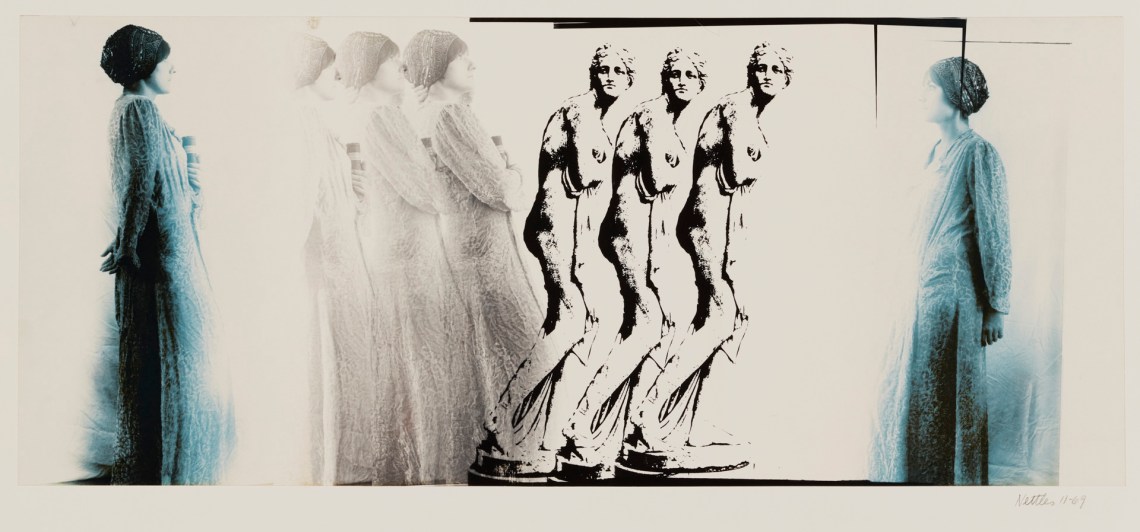

Nettles’s work has always defied categorization. In 1969, when she was in her early twenties, she created several works that combine photography with other media to form hybrid objects. For Swamp Box: Birth of Venus, she used an oak cabinet to house tiers of diminutive floating islands composed of prints, photographs, cloth, and sewn elements. For The Skirted Garden, she stitched lace, nylon stockings, and other fabrics over a landscape painted on fabric and then attached a red skirt and a satin slip (visible when the skirt is lifted) along the bottom. For Imaginary Prairie, she made etchings of pillowcase hems and thrift-store hairnets, printed them serially on muslin, and then stitched three prints together into a long horizontal landscape. The lacy layers, which build to an open space at the top of the piece, appear as both geological strata and a bird’s eye view.

Nettles’s materials, and also the way she returns to certain forms and images—sometimes even using the same negative in different works and incorporating finished works as elements in new ones—remind me of Louise Bourgeois’s art, in particular Ode à l’oubli (2002), a book comprising thirty-two fabric collages that not only incorporate forms (spirals, grids, round shapes, and so on) that recur throughout her earlier oeuvre but are made from the literal materials of Bourgeois’s life: nightgowns, scarves, and monogrammed napkins. The book’s construction includes embroidery, weaving, and appliqué, processes that make reference to a childhood spent at her parents’ tapestry-restoration workshop in France. For Nettles, this way of working was intuitive. In her book The Skirted Garden: Twenty Years of Images (1990), she writes:

Advertisement

To work in materials with an approach labeled feminine was not a conscious feminist decision. Having been educated exclusively by male studio artists with no female mentors, such an idea would never have entered my head. I just knew I felt comfortable sewing and that I had always loved fabric. I also had a lot of self confidence as a result of my upbringing and was unafraid to experiment with ideas I felt strongly attracted to.

Nettles studied painting and printmaking as an undergraduate at the University of Florida and took her first photography course, with the experimental photographer Robert Fichter, during her senior year. In 1970, she earned a master’s degree in painting from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The university was known for being a hotbed of artistic ferment: in 1958, Lejaren Hiller founded the Experimental Music Studio there, and later it was the site of several “happenings” staged by John Cage, including A Passage Without Definition (1967) and HPSCHD (1969). But Nettles didn’t feel their influence. The school’s art departments remained discrete, with painting located off campus, and a formalized photography curriculum didn’t exist, so there was no opportunity for official interdisciplinary experiments. “Cutting and sewing photographs was seen as an outrage,” Nettles wrote in The Skirted Garden. Because she had chosen not to take a straight photography class, she wasn’t permitted to use the school’s darkroom and had to find a private one (in a freezing basement, she recalls, where she printed “in a thrift-store fur coat and gloves”) in order to continue her cross-media pursuits.

In 1970, two of Nettles’s machine-stitched photographs were included in the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark exhibition “Photography into Sculpture,” curated by Peter Bunnell. In that period, and even into the 1980s and 1990s, according to Bunnell, the museum’s departments operated as distinct domains. When he briefed the painting and sculpture department on his exhibition, its curators, in what seems to have been an attempt to cordon off his show, suggested changing the name to “Three-Dimensional Photography.” Bunnell had identified a new direction in photography, referring to the artists in the show as “photographer/sculptors.” At the forefront of these photographic explorations was Robert Heinecken, whose mass media–based work involved a darkroom but not usually a camera. He had established the photography department at UCLA in 1963 and was influential in the Los Angeles photography scene. In fact, the majority of the artists in the show were from the West Coast, from Los Angeles to Vancouver.

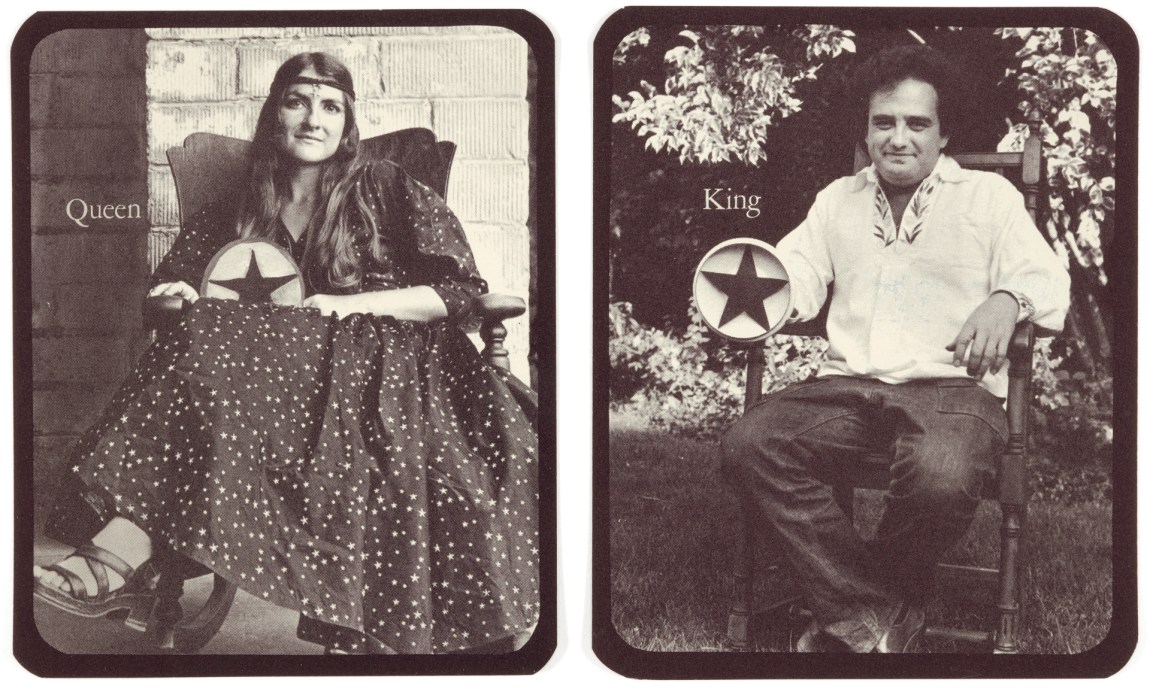

Nettles, however, was far from this world. Before moving to Urbana-Champaign, she spent a brief period studying and teaching at the Penland School of Craft, in rural North Carolina, a community to which she returned periodically over the next three decades and where she began her best-known work, Mountain Dream Tarot (1975), the first-ever fully photographic set of tarot cards and among the many card decks she has made. Her first post-university teaching jobs were in Rochester, New York, first at Nazareth College and then at the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). After a stint teaching in Aspen, Colorado, Nettles moved to Philadelphia to teach at the Tyler School of Art. In 1974, she settled again in Rochester, where her children, Rachel and Gavin, were born. A decade later, the family relocated to the Urbana-Champaign area, where Nettles still lives and makes art, for the remainder of her university teaching career. Her solo exhibition history has been exclusively in the care of regional museums, the small publishers of the institutional art world. That distance from art-world hubs perhaps granted Nettles a freedom to continually reconfigure her medium.

Teaching has been an essential part of Nettles’s practice, and her interest in experimental techniques has served her own work as well as her desire to pass along alternate methods to her students. “It is reassuring to think that sometimes something that I have nurtured and grown, and here I mean an image or an idea, can be split up, shared, and even better yet, transplanted into someone else’s garden,” she writes in The Skirted Garden. She published an instructional record of these many processes, Breaking the Rules: A Photo Media Cookbook, in 1977 and in two subsequent editions, selling some 30,000 copies.

Advertisement

But her teaching career was not without frustrations. Around 1970, when she was applying for jobs, she cut up a photograph of herself into two-inch squares and inserted the pieces at random into the pockets of a 35mm-slide sleeve organizer. Her body is misaligned, like a woman sawn in pieces at a magic show and left askew—no longer the sum of her parts. Harvest of Memory includes that image as well as a panoramic photograph of RIT’s art faculty taken in 1980, when Nettles was an instructor there. The photograph, used for a department-wide exhibition announcement, shows fifty-four men and two women, and as I combed the long line of men—in jackets and ties or shirtsleeves, creating a long, nearly unbroken row of pants—I kept returning to the figures of the two women, separated by eleven colleagues. They are posed differently but wearing identical outfits. They are the same woman: Bea Nettles.

That year, Nettles’s sole female colleague at RIT, Kathleen Collins, was on sabbatical, and Nettles’s repeat appearance in the photograph was meant as a joke. But what’s the joke exactly? That women are interchangeable? That in the wide field of artmaking, one woman’s practice is synonymous with another’s? Nettles was evidently in on the joke, having stood in for Collins, though I’d guess her part was more subversive than her colleagues may have supposed. When she had taught at RIT almost a decade earlier, she was sometimes mistaken for her colleague Betty Hahn. In an interview in 2012, Nettles recalled the department’s inhospitable atmosphere:

Most of the teachers at RIT thought I was kind of flaky. They weren’t rude to me; they just dismissed me. One would always barge in to tell me to wrap things up because his class was going to start in five minutes. Even in some mainstream media, Betty Hahn and I were mixed up and reviewed as Bea Hahn and Betty Nettles. There were teachers at RIT who never learned my name. They called me Betty after she left. We’re two different women. It’s worth learning our names.

Bookmaking became a central preoccupation for Nettles in the mid-1970s. Initially, she assembled sequences of photographs and photographic collages in three-ring binders and notebooks, then began to hand-stitch and self-publish books. Under her imprint Inky Press, she has published more than thirty photobooks. “I loved the technology involved and found my background in printmaking to be very useful,” Nettles wrote in The Skirted Garden. “Bookmaking also allowed me to work in sequences, to incorporate words and images, and to have my work reach an alternative audience.” Even within the form of books, Nettles’s activity has been wide-ranging. Events in the Water (1973) and Events in the Sky (1973), two of her earliest books, are playful taxonomies: snapshots of feet disappearing in a pool and a pair of dogs milling about in a muddy puddle; a sign hung across a street, its rigging invisible against white clouds, and divers suspended midair.

Nettles’s mother, Grace, raised five children and then returned to school at the age of fifty, becoming an English professor and a poet. When Nettles was a child, her mother had imbued in her an attentiveness to sound, developing her “love for spring peepers…the voice of the mourning dove, hoot owl, and red bird.” Between 1973 and 1988, Nettles produced four books pairing her photographic images with her mother’s poems, linking her own dreamlike imagery with her mother’s words, which were also often about the natural world and women’s experiences. In one of these, The Imaginary Blowtorch (1973), Nettles screen-printed photographs on transparent sheets of mylar so that, as the pages are turned, the images seem in conversation with the poems they overlay. In another, Of Loss and Love (1975), the photographs and poems sit opposite one another, both pictures and text alternately cast in gold, sepia, and reddish tones that evoke the wistful qualities of the title. In a poem about mothers, Grace writes,

She showed them ways….

How to hear water crossing stones, make music on a comb,

And wash a dog.

How to pull radishes and ring bells.

How to build fires and how put them out.O yes she taught them things,

But most of all she showed them ways,

And taught them to go out

Looking for ways, habitually.

The imagery in Grace’s poems feels fantastic in its everydayness, a sensation that, along with its confidential tone, recurs in the photographic series Nettles made with her own daughter in the next decade.

In the early 1980s, when the demands of parenting kept Nettles from the darkroom, she began to use a pinhole camera, which allowed to her to manipulate a small scene in a single image, rather than through multiple exposures. Her days were spent in the intimate realm of toys and make-believe, and those objects and elements became props in her series Close to Home (1980–1982). These photographs read like wondrous dioramas, snug and inviolable scenes as a child might compose them. In Dish and Spoon (1980), a ceramic cow in a dress, a soup spoon, and a small plate—a Mother Goose menagerie—traipse over a hillock against a pale pink background of lace, blurred as though in motion.

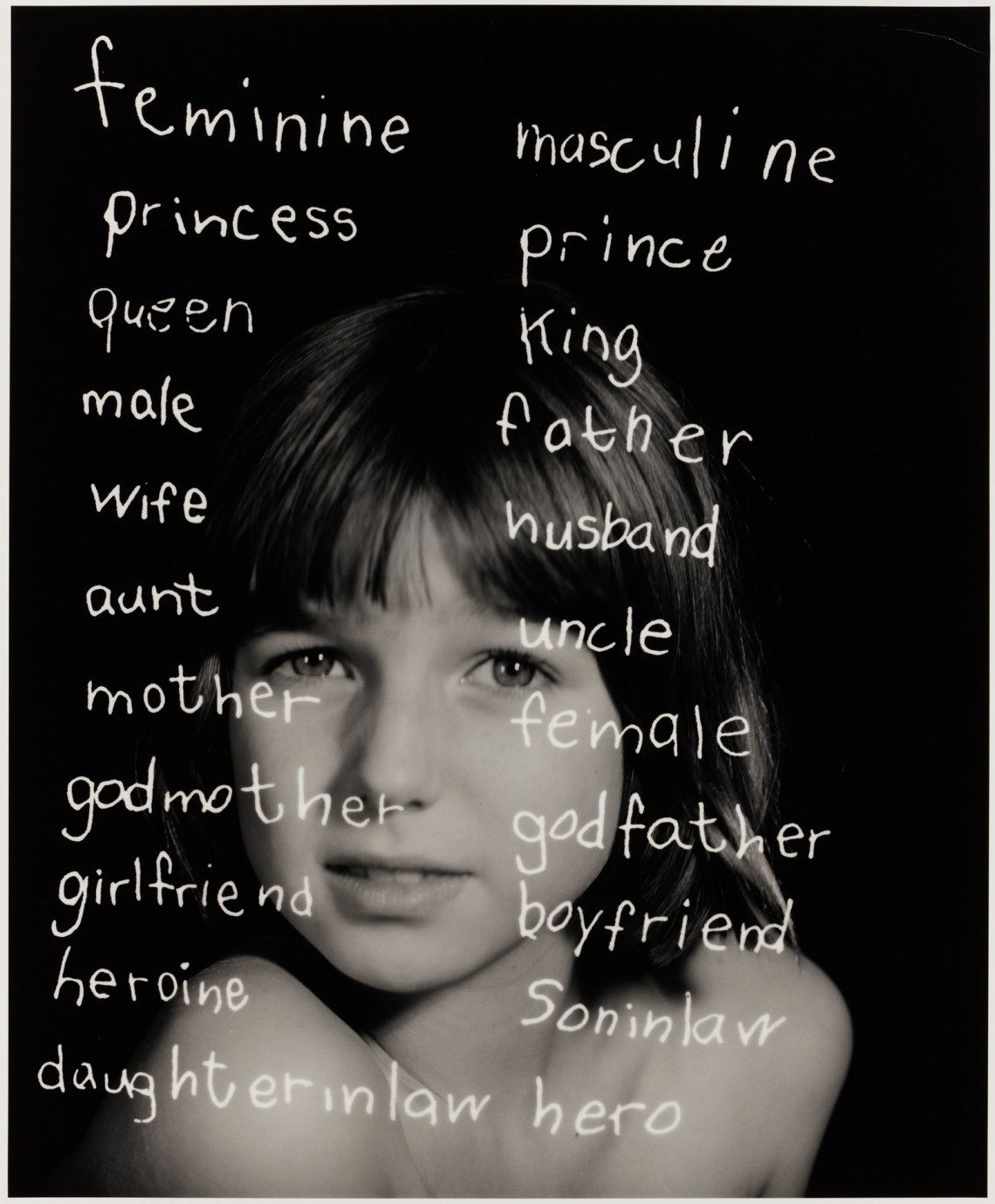

For the series Rachel’s Holidays (1984), Nettles spent more time in the darkroom, using a dye-imbibition process that produced saturated colors. Her daughter was her collaborator; together, they made winsome tableaux—childhood idylls and images that show a curiosity about patterns, textures, and forms. Many resemble still lifes of sand, shells, fabric, and small toys, with Rachel’s body or arms in the foreground, actively arranging the scene or just having done so. Anxiety and worry make their way into this period, too. The book Life’s Lessons: A Mother’s Journal (1990), taken with Polaroid 4×5 and 20×24 cameras and in stark black and white, teases out parental fears—predators and kidnappings, illness and nuclear destruction—and, from Rachel’s and Gavin’s points of view, reflects on identity and social pressures.

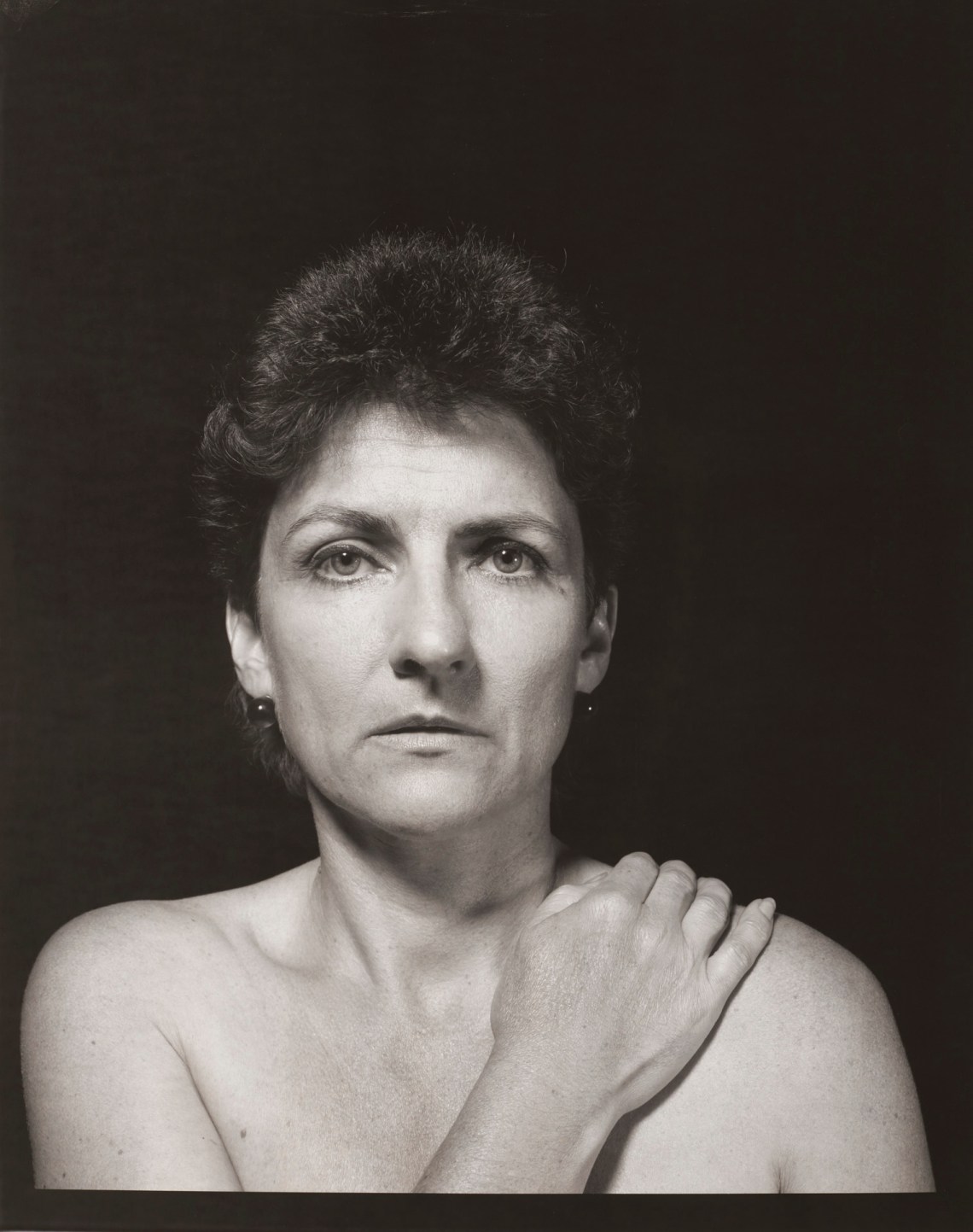

As she got older and her children grew up, Nettles turned her camera more fully on herself again. She produced the book Turning 50 (1995), exploring in black-and-white photographs her changing face and translating into visual terms the physical feelings that accompany an aging body. She sets a photograph of her legs mottled with varicose veins in a triptych with shots of rippled sand on a lakefront and the dappled bark of a knobby tree. The diminutive, spiral-bound book The Observer (2005) presents five self-portraits taken between 1956 and 2000. Each image is printed twice, on facing pages, and the area of the eyes is cut out so that, as the pages are turned, the face on the verso shows through to eyes from 1956, and the face on the recto to those from 2000, erasing the distance between the child and the older woman. Later, when Nettles was diagnosed with cancer, she produced Hair Loss (2007), an accordion-fold book that matter-of-factly records her progressive baldness from chemotherapy and her hair’s slow regrowth, with strands of her own hair embedded in the endpapers.

In 2008, Nettles made a pair of photobooks inspired by Norse mythology after a residency in Hafnarfjordur, Iceland. One of them, Fate, Being, & Necessity, is concerned with the three Norns—the interconnectedness of past, present, and future, represented by a trio of women at different stages of life. It is a flag book, a sculptural book in which each page is cut into thirds that can be turned independently, producing new combinations of the images and mimicking the intertwining of the women who control human destiny. The other, Mind & Memory, is named after Odin’s ravens, Huginn (mind) and Muninn (memory), who fly around the world and report back to the god on what they have seen and heard. Odin worries that Huginn will disobey him, but his greater fear is that one day Muninn will not return. The book’s spine is bound in Icelandic fish leather. Both volumes contain painterly photographs—marbled swirls of gray, brown, and black earth, water, sky, and stone.

In 2010, Nettles began photographing surnames on tombstones that also serve as standalone words. From this collection, she composed stories and poems (“KEEN DEW WATERS ELDER BERRY BOWERS” and “EAGLE FEATHERS CROWN RIDGE RIDER”), collapsing the difference between written and visual languages. Though predicated on a sense of mortality, this single form has allowed Nettles to make works that comment on language, literature, the seasons, history, and current events. Last summer, she created the accordion-fold book Head Lines: Worlds Warning, a chronology of the Covid-19 outbreak.

There is a kind of magic in Nettles’s work, as though she isn’t recording reality in her images but creating it. This feels true of her process as well—its unique combination of chance and manual manipulation. The focus of much photography is the outside world; Nettles turns the camera on her interior life, producing images that are reflective and representative of her memories as well as of her feelings. As she made her own aging body the subject of her work, she continued to reflect on her past art—in particular, the task she had set for herself early on of apprehending the plurality of women’s experiences. “Through our art, teaching, and very lives,” she wrote in her book Complexities (1992), “let us confirm our cycles, the magic of our bodies, our abilities to make a whole out of parts.”