Shortly after September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush announced a new policy required by a new kind of war. Alleged al-Qaeda terrorists would be tried by military commissions that offered few protections for the accused; ordinary courts with the standard full-dress guarantees and protections would be out of bounds. Detainees would have to be “treated humanely,” the order stated, and the trials would have to be “full and fair.” But no rules of treatment for accused “terrorists” reflecting international standards were specified.

“Well, this is fucked up,” remarked civil rights lawyer Joseph Margulies to his wife, Sandra Babcock, a public defender with a deep interest in global human rights, as they sat at their Minneapolis kitchen table reading the newspaper over breakfast. Bush’s announcement seemed like a transparent attempt to create a second track of justice for terrorists, one that would not require the familiar safeguards of the criminal process, or even the wartime rules prescribed by the Geneva Conventions of 1949.

“We should call Michael Ratner,” Sandra replied.

They did. Ratner, a former antiwar student activist of the Vietnam era, had spent his entire career at the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), where he had become well-known as a leading litigator. By 2001, he was the group’s president; to many, he in effect was the Center for Constitutional Rights. Ratner considered the Bush order unequivocally “the death knell for democracy in this country” and threw himself into action.

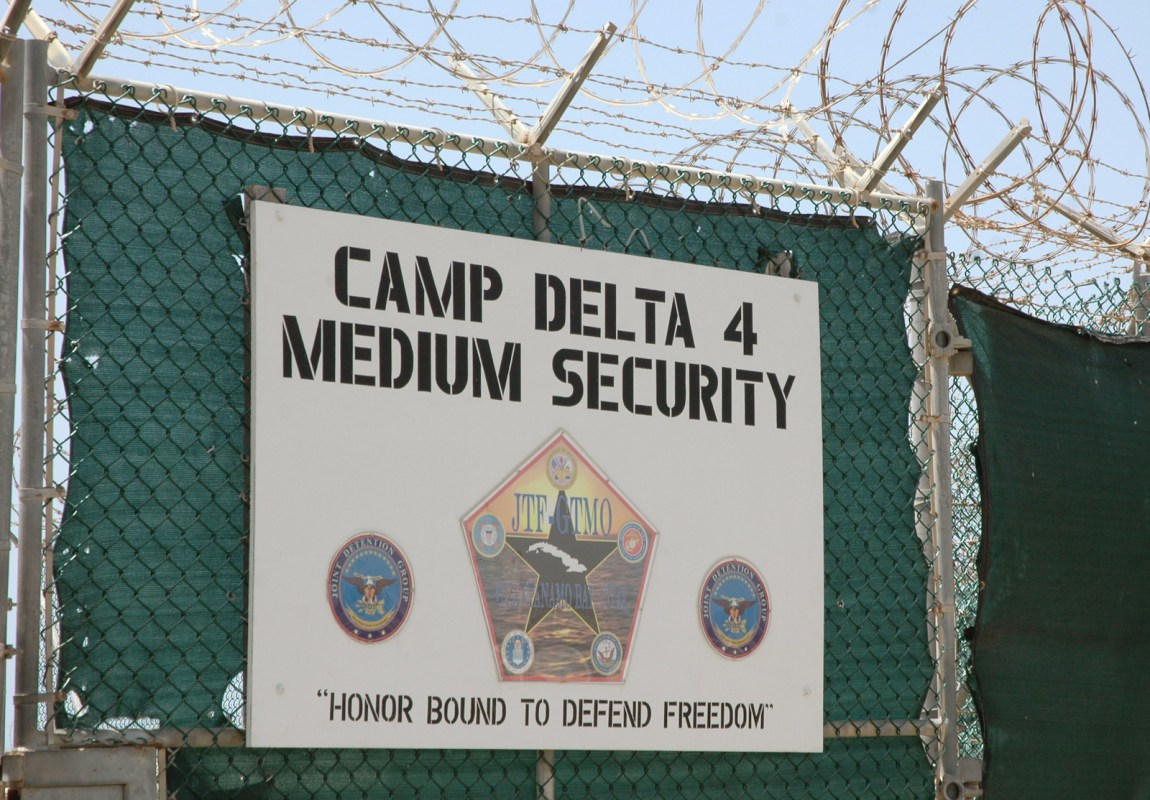

Three years later, the desperate legal challenge Ratner led against the military commissions scheme seemed to be paying off. Already, Shafiq Rasul, a British citizen whom Americans had rounded up in Afghanistan in 2001 and interned at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, had been released, without being tried, and returned home. But other plaintiffs remained in the case of Rasul v. Bush that Ratner had brought. Ruling in the case a few months after Rasul left, the Supreme Court held 6–3 that federal courts could exercise their power to issue writs of habeas corpus, and thereby review the detention of accused terrorists being held indefinitely. Providentially for Ratner’s litigation, just days after the Supreme Court had heard oral argument in the case, scandalous photos of prisoner abuse by American forces at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were leaked. No doubt, this had a bearing on the court’s decision.

Despite Ratner’s apocalyptic initial view of the Bush order, that victory and a few others helped dispel worries that the so-called war on terror was going to be fought in a “state of exception” without legal constraint and legitimation. The same justice who authored Rasul, the late John Paul Stevens, followed up in 2006 with an epoch-making opinion in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, which clarified that—at the very least—the Geneva Conventions Common Article 3 applied to the war on terror. And because that article requires trial of detainees by a “regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples,” the military commissions Bush had planned since 2001 were inadequate. The decision implied that whatever global struggle the US wanted to wage against terrorism would have to be conducted under the applicable international law—because nothing less than the war’s legitimacy depended on it.

By the time of Rasul, in 2004, hostilities had expanded from Afghanistan, the home base from which al-Qaeda had planned and executed the September 11 attacks, to Iraq—despite the nonexistence of any connection between the country’s leader, Saddam Hussein, and those attacks. When the Hamdan decision came down, the invasion of Iraq and the capture of Saddam had given way to a failing bid to pacify that country, with hundreds of thousands of civilians dying in the carnage and disorder. The international law governing the conduct of hostilities, enshrined in the Geneva Conventions, had become central to Americans’ sense of limits. But if there was any international law rooted in the United Nations Charter’s prohibition of aggressive force that forbade the Iraq intervention in the first place (since the US Congress had approved the war under domestic law), it was not a limit that activists pressed successfully, or one that the Supreme Court ever enforced.

The debate about commissions had, indeed, grown into a full-scale bout of soul-searching over the treatment of detainees, because of the other policy choices—especially the approval of torture—that Bush had made in the weeks after September 11 but kept secret until details were leaked. As the Iraq War began to go sour, there was a moral reckoning in the US around the mistreatment and even torture of prisoners, but it did not result in any constraint on the war on terror’s expansion and extension. Instead, the outcome of the debate over the fate of prisoners would permit many to bless US belligerency, foregrounding America’s concern for legal propriety and the humane standards of international law.

Advertisement

It is for this reason that the early years of the war on terror were crucial to its perpetuation even now—and not merely as the time of a heroic assertion of law, by left and right, in the name of humanity. In contrast to what occurred after the My Lai revelations in the Vietnam era, American public awareness of war crimes did not end a war but helped reset one: the US reclamation of humane standards in fighting helped make war more durable.

This was a tragedy for America—and, God knows, for those living across a wide arc of the globe as the war expanded and the years passed—but it was also a tragedy for Michael Ratner.

In the years after September 11, 2001, Michael Ratner set aside the why, whether, and how long of America’s global wars and concentrated instead on legally battling for controls on how they proceeded. In the annals of recent history, no one, perhaps, has done more than this leader of the Center for Constitutional Rights to enable a novel, sanitized version of permanent war. By legalizing the manner of the conflict, Ratner paradoxically laundered the inhumanity from what began as a brutal enterprise by helping to recodify a war that thus became endless, legal, and humane.

The two Boeing 767s that al-Qaeda terrorists crashed into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York, and the third plane that slammed into the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., were the catalyst—it was no wonder that the US responded by activating the military supremacy it had enjoyed around the globe since World War II. The scenes from Lower Manhattan, where nearly three thousand died, were nightmarish. Not for centuries had a foreign adversary inflicted such losses on the US mainland. Within ten days, President Bush promised justice in response to an “act of war” by terrorists.

From near the start, it was clear that international law—at least, the part that dealt with regulating fighting—was going to be at the center of debate, more so than in any American war before. Bush’s lawyers, led by the now notorious John Yoo, worried enough about international law’s prohibitions that their first move was to reinterpret them as not applicable in this new scenario of global counterterrorism measures. And so, in a backhanded, revealing acknowledgment of the rising relevance of international law, they tried to lift its requirements. The expectation of “humane” war had become such a powerful cultural norm and legal imperative that it became essential to construct an escape hatch at the last minute.

Bush, nonetheless, had little trouble going to war. After Congress rapidly authorized armed force against al-Qaeda and the Taliban, the United States offered almost no argument about the propriety under international law of attacking the latter to get to the former. To object to US intervention in the fall of 2001 would have been spitting in the wind. Almost all international leaders felt the obligation of solidarity toward the victims of terrorism in the country’s moment of mourning, allowing the first domino to fall in what would become a state of permanent war. The world looked on tolerantly as the US and the UK formally commenced Operation Enduring Freedom less than a month after September 11: the campaign started with air strikes in Afghanistan on October 7.

It would give John Yoo, and his ilk, too much credit to suggest that he intended to guarantee the propriety of the war on terror by stooping to conduct, like torture, so vile that its critics were baited to remove it—at an ultimate cost of leaving the war otherwise intact. Nevertheless, that was the result.

One reason for this, whatever Yoo’s intentions, is that his arguments gave some who supported America’s wars a highly idealistic mission: to return virtue to a foreign policy globalism that had gone awry. In the critical years of the mid-2000s, a genuine longing for humane American war became widespread, especially among early supporters of the war on terror, and the disastrous Iraq intervention in particular, looking for a moral sequel to redeem their earlier mistake. As for those more doubtful about America’s wars, the contest over the humane treatment of prisoners and its outcome posed the challenging question of what risks they courted in stigmatizing those wars’ conduct if they could see no practical way of opposing them. Michael Ratner offered an especially vivid example of this dilemma.

*

“I was born during the war,” Ratner commented, in a posthumous memoir that he finished drafting only as far as the years before 2000. “But as someone born in the United States, which has been at war for more than seven decades, this hardly narrows it down.”

Advertisement

Ratner’s Jewish parents had immigrated to America from Bialystok, Poland, in the 1920s, and settled in Cleveland, Ohio, where their son was born in 1943. A generation older than his Bush administration antagonists, Ratner’s consciousness was formed as a twenty-five-year-old student at Columbia Law School on a campus rocked by student activism against the Vietnam War. “Like so many people around the world,” he later recalled, “I was politicized first in 1968.” After he graduated, Ratner joined the Center for Constitutional Rights in 1972. The organization, founded in 1966, was still a new actor in the realm of civil rights; Ratner would work there, on and off, until his death from cancer, in 2016. Less kempt than his conservative and straitlaced adversaries, Ratner would nevertheless don a suit for court, accepting the rules of the lawyerly game as the price of victory.

Ratner’s brother became a real estate magnate, and his sister a Fox News commentator, but his identification with leftist causes remained unwavering throughout his life. He idolized Che Guevara, the Argentine hero of the 1959 Cuban revolution, and himself traveled to Cuba in the 1970s to work for the country. In the late 1990s, Ratner promoted a lawsuit filed in Havana City against the United States for $181 billion in damages, to make up for forty years of “acts of aggression.” On one occasion, when he was being interviewed in 2013, on the day after the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, Ratner remarked in passing that September 12 was, in fact, the date of the 1973 American-supported coup against Chile’s social-democratic president Salvador Allende.

Ratner became an associate of famed radical lawyer William Kunstler, a cofounder of the CCR, who would later marry Margaret Ratner, Michael’s first wife, after their divorce. Kunstler was well-known for defending unpopular agitators, from the rioters at the Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968, to draft card burners the same year, to Black Panthers and Weathermen later.

Unlike the mainstream of the human rights movement, Ratner always put peace ahead of humanity in war. One of the greatest causes in his early career was the attempt to enforce the War Powers Resolution, a 1973 act that attempted in the dying days of Vietnam to restore some congressional authority over foreign wars. Among other things, the act mandates a cutoff after only sixty days for “hostilities” that the president initiates without legislative signoff. Ratner later joined the progressive Catholic priest and former congressman Robert Drinan—who was originally elected on an antiwar platform in 1970 and had voted on the resolution when it passed—to sue the Reagan administration in an attempt to have the law enforced after the president had sent “military advisers” to El Salvador in 1982. They lost the case, but they did not give up on the law controlling war.

Ratner’s activism on this front continued through the turn of the millennium. He hoped that the end of the cold war would mean a reset, allowing Congress to rein in a belligerent executive. In the early 1990s, he helped another group of congressmen, led by Oakland’s Ron Dellums, to sue George H.W. Bush in a test case to require legislative authorization for military intervention before the Gulf War formally began. Ratner lost again, yet he persisted with such litigation for the rest of the decade, including under Bill Clinton’s presidency.

Ratner and the Center for Constitutional Rights behaved in this period quite differently from Human Rights Watch and other groups that focused on atrocities in war, avoiding a search for limits to the starting and waging of war in order to maintain an officially apolitical stance. Such humanitarian outfits had long ago resolved to monitor whether wars were being fought legally, but almost never to take sides on whether they had a legal basis, or needed to stop. Ratner, on the other hand, trained his sights almost as much on America’s violations of international law’s prohibition on force as on the damage he decried to domestic law controls such as the US Constitution and the statute governing war powers. In May 1991, he gathered in New York City with dissident former attorney general Ramsey Clark and others to stage a rerun of the mock war crimes tribunal that the philosopher and peace campaigner Bertrand Russell held during the Vietnam War. Like Russell, Ratner followed the priorities of Nuremberg’s indictment of Nazi leaders after World War II in condemning America’s “aggression” as its worst war crime, rather than isolating violations of humane standards during the 1991 invasion of Kuwait.

Almost five years before the Iraq invasion under President George W. Bush, Ratner rightly complained that President Bill Clinton had pushed far beyond what the UN Security Council resolutions controlling Saddam Hussein’s weaponry permitted, in a flagrant violation of the international prohibition on the use of force. Along with his frequent ally and CCR colleague Jules Lobel, Ratner predicted that America’s “tendency to bypass the requirement for explicit Security Council authorization, in favor of more ambiguous sources of international authority, will probably escalate in coming years.” The ink on this warning was still wet when the United States bombed Iraq for four days in December 1998, illustrating, as Ratner and Lobel said, a “painful reality of superpower unilateralism.”

For all Ratner’s efforts to invoke law that forbids starting wars, however, the reality was that the cause died a slow death after Vietnam, even among progressives. In a 1999 op-ed about war powers for The Wall Street Journal, John Yoo asked mischievously, “Where Have All the Liberals Gone?” as he reviewed the abandonment of what was becoming a concern as idiosyncratic on the left as it was on the right.

Ratner wholly rejected any romance of American war as an idealistic and moral tool. Breaking with many fellow progressives, he was particularly upset by the rise of “humanitarian intervention” in the 1990s, protesting the US and NATO’s illegal bombings of Kosovo in 1999, which the United Nations had never approved. Exceptions to the rule against using force were generally used as pretexts, Ratner insisted; and even if they were not, they led to abuses by less high-minded powers, once precedents were set for breaking the law in a just cause. It had been Adolf Hitler, Ratner and Lobel wrote, who most notoriously claimed “to intervene militarily in a sovereign state because of claimed human rights abuses.” Although “NATO is obviously not Hitler,” they went on, “the example illustrates the mischief caused when countries assert the right to use force on such a basis.”

Through the late 1990s, Ratner’s essential concern remained war itself. The US had disdained even the pretense of compliance with international rules governing the use of force in Kosovo. In the international policing of Iraq during the 1990s, “at least the US at that point was making a claim that had some kind of implicit authority from the United Nations,” Ratner commented to Amy Goodman in a 1999 episode of Democracy Now! No more. “International law is a dead letter to a large extent with regard to intervention,” he reported glumly. “We’re living in Rome right now.” On another episode, Ratner denounced the intervention outright as “a crime of aggression.”

Ratner was gloomy about the geopolitical implications. “What can you say except [that] the United States is becoming a rogue superpower?” he asked his host. What Michael Ignatieff called the “virtual war” of Kosovo—in which NATO forces led by the United States Air Force enjoyed a lopsided superiority from the air, bombing the forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia with little exposure to risk—Ratner found disturbing. He chillingly anticipated the coming of a new, cleaner form of conflict that would replace the dirty, hands-on methods against which Ratner would turn to campaign after September 11, 2001: “You can basically push buttons and bomb people.”

*

On September 11, 2001, Michael Ratner was jogging past the World Trade Center near his Lower Manhattan apartment, when the first plane struck. His brother was in 7 World Trade Center that day, and survived. Afterward, Ratner said that he, too, shared the mood “of obviously wanting to stop this, to never have it happen again, and to punish the people who did it.” He wasn’t as sure, this time, that there was a choice other than war. But the sorrow of a school friend of his children’s who lost her father in the attacks also inspired in Ratner this thought:

Unfortunately and sadly, people around the world have lost parents forever, whether that be in Israel or Palestine, or in Lebanon, or in Cambodia. And what it did really, in a way, thinking like that, actually deepened my resolve that we have to try and find alternatives to the use of military force.

Ratner rued the day that Congress approved force against not a defined foe but a general method of violence—terrorism—without prescribing any end date. Three days after Congress voted, providing authority for a war on terror that has not been revoked since, Ratner appeared on Democracy Now! to worry about the “rhetoric” of “revenge,” of “pulverizing other countries,” and “bombing them into submission.” And without time limits, he said, Congress had allowed that “the president, under this resolution, can make war forever.”

Ratner may have been right that stopping the war on terror was not then realistic, but in this moment, he also chose to drop any litigation testing the legality of wars. Instead, he turned single-mindedly to defending the rights of those abroad who were swept up, sometimes innocently, in the conflict. What was the point of pursuing his old advocacy against war itself? There was no hope, as Ratner saw it, in returning to court for that thankless task. “We just gave up,” he told the Harvard law professor and former Justice Department official Jack Goldsmith, in 2010.

Not that Ratner’s legal activism against the conduct of the global war on terror—initially, itself a lonely undertaking—was much more likely to succeed. He faced opposition within the CCR for doing something so controversial as to defend the rights of individuals America had defined as “enemy combatants,” not to mention in the broader community of civil libertarians. When asked at the time, in 2004, by David Cole, his disciple and later national legal director for the ACLU, if Ratner thought his filing in Rasul had a chance, he replied: “None whatsoever.” Yet he doggedly pursued that tactic in the years that followed, even after successive losses in lower courts.

His persistence paid off. Despite the long odds against making America’s wars after September 11 legal in the way they were fought, Ratner enjoyed providential success. In part because of the bold extremity of Yoo’s denial of the relevance of law to the fighting of the war, the Supreme Court awarded Ratner a surprise win in Rasul. Both before and after that breakthrough, Ratner led the creation of a so-called Gitmo Bar that filed hundreds of habeas petitions for those interned at Guantánamo, and he publicized the victimization of his clients tirelessly. But Ratner’s victories in cases like Rasul and Hamdan coincided with the increasingly popular move, especially as the Democrats angled to succeed to the presidency, of fixing America’s post–September 11 posture without undoing it altogether.

*

This is why the responses to the Iraq War—starting in 2002–2003, and becoming only more contested over the years following the Abu Ghraib revelations in 2004—were the true crucible for endless if more humane war. In the fall of 2002, the Authorization for the Use of Military Force in Iraq garnered the votes of a full three-quarters of America’s legislators. The Bush administration offered a grab-bag of explanations for the need to invade, including Saddam Hussein’s supposed connection to international terrorism, the crimes of the Iraqi state against its people, epitomized by his “rape rooms and torture chambers,” and, at the top of the list, his development of weapons of mass destruction.

A few doubted whether enough evidence of WMD existed, but most American experts, right and left, gave Bush the benefit of the doubt. By the time Operation Iraqi Freedom began on March 20, 2003, American popular support for the spectacular invasion was running high. In fact, it took two long years to cool even to tepid levels. Ratner may have been right to conclude that his antiwar activism, which had by then failed for decades in the US, consisted of cries in the wilderness.

Although his work had generally shifted its focus to making the war on terror humane, Ratner did revive his old commitments as the Iraq invasion loomed in the summer of 2002. In a letter to the editor at The New York Times, he and his colleagues at the CCR wrote that the “prohibition on aggression constitutes a fundamental norm of international law and can be violated by no nation,” and he circulated among followers a primer against the coming military action.

Nor was he alone. Americans had taken to the streets, joining the world in what was, judging by numbers of people participating, “the largest antiwar movement that has ever taken place,” as Barbara Epstein (a professor at the University of Santa Cruz, not the former co-editor of the New York Review of Books) noted in Monthly Review. On February 15, 2003, coordinated marches clogged avenues in most American cities, although they were dwarfed by the tens of millions who protested outside the country, especially in European capitals, decrying the coming storm. But as the historian Andrew Bacevich mordantly remarked, “the response of the political classes to this phenomenon was essentially to ignore it.”

It wasn’t until after April 2004, when CBS News broadcast details of the sickening visual mementos of abuse and torture that US troops had taken at Abu Ghraib, an Iraqi prison used by the US military as a detention facility, that a genuine phase of national soul-searching occurred. The noble attempt by Ratner and an increasingly large number of concerned citizens, doubting journalists, and movement activists to stigmatize the worst excesses of the war on terror, which had begun with nary a second thought in 2001, took the form of a protest against inhumanity.

With the US already engaged in a metastasizing conflict, Ratner emphasized the courts as places where blows for justice within the continued war were still credible. Dreadful images of prisoner abuse, along with reporting about conditions at America’s Guantánamo facility, were more horrifying and persuasive than abstract and contested claims about the legality of America’s wars. Many, indeed, found the mistreatment and torture a useful bridge to indirect opposition to an enterprise they had not previously repudiated. But the timing of the critics’ attempt to anathematize its cruelties, coming out against the war after the fact, meant that their approach could and did work to enable the war’s continuation.

Abu Ghraib, Guantánamo, torture: these became the watchwords of a generation. Barton Gellman and Dana Priest of The Washington Post had reported on rumors of abusive practices as far back as December 2002, but to most Americans, it was not yet credible that the US could stoop to atrocities. That, eighteen months later, the Abu Ghraib photos had the effect they did was due not so much to the visual confirmation of abuses they provided as to the fact that the Iraq “triumph” had by then revealed itself to be another costly quagmire. Consciousness of American immorality and worries about the illegality—if not of war itself, then of its brutality—spiked. And leaks of memos confirming that Yoo and others had sidestepped the law nurtured this belated discovery of moral insight.

Even then, it was a highly partial insight. What The New Yorker journalist Jane Mayer memorably called “the dark side,” appropriating a saying of Vice President Dick Cheney’s, came to refer across several momentous years of moral panic not to war itself but to its means and methods.

In the ensuing debate, Yoo was criticized not for opinions declaring wars legal under international law after 2001, but for ones attempting to exempt the war’s conduct from it. Far more flagrantly than the beginning of the forever war in Afghanistan two years earlier, the Iraq intervention had been illegal under the applicable international law prohibiting force. In defense of the 2003 invasion, Yoo relied on prior authorizations from the Security Council—dating from as far back as 1990—as permission slips for this new war and, indeed, regime change.

Unlike the memos permitting the country to conduct the fight without constraints, the opinions Yoo wrote explaining the legal justification of the Iraq War never attracted much controversy in America. Barack Obama ordered Yoo’s torture memos shredded on his first day in office—but his equally radioactive ones authorizing the entire era of war remain on the books even today. Yoo’s claims were accepted by America’s coalition partners, though it is now known that the intense resistance of Britain’s Foreign Office lawyers was overcome by their own minister on the road to the intervention. In America, the contrast between the disparate responses to, on the one hand, the Bush administration’s lifting of international law on the conduct of the war on terror and, on the other, its twisting of international law to enable the Iraq War was extremely striking. One stirred national passions; the other went largely unremarked.

*

Even when focused wholly on detention, Ratner’s objective was never really to make American war more humane, though he certainly found some of the American practices he learned about sickening. Ratner burned with rage over the “horror” (his word) of Guantánamo, but what he cared most about was not diminishing suffering in potentially endless war but ensuring that civil liberties did not die; and he wished to ensure that the legal system remained a forum for challenging power. When his son was studying the Magna Carta in high school, Ratner was struck by its promise that no man is above limitations—it was “about the king obeying the law, or the president obeying the law,” Ratner wrote.

In a reflective later moment, Ratner came to the conclusion than his most agonizing failure had been his failure to destroy “the war paradigm.” This, he told Goldsmith, was “the biggest loss we’ve had.” Stuck with that paradigm, and despite coming from the far left, he occupied a position strikingly similar to that of some conservatives who, in contrast to Yoo, wished to place the war on terror on a solid legal foundation. Ratner differed only in his insistence on constraint not to buttress power, and on legalization not to secure legitimacy, but rather because power without limits is tyrannical.

By the end of his life, Ratner was reviving, one final time, the cause of trying to place constraints on using force abroad, ones he had once hoped to give some teeth. As intervention loomed in Libya, in 2011, under President Barack Obama, Ratner inveighed against the policy debate that was taking place in Washington, D.C., with no mention that “such an action would be illegal,” regardless of any justification of it as a humanitarian intervention. Two years later, when Obama decided against intervening in Syria without congressional support, Ratner called it “the first time I’ve actually seen resistance to going to war in this country since 9/11.” And he returned to the thankless task of seeking enforcement for the War Powers Resolution, a statute that had been all but shredded in the meantime.

No wonder: Ratner feared that the war on terror, even if conducted more humanely, could have long-term effects in degrading American life. As he reported in 2005, he kept before him the specter raised by the ancient Greek historian Thucydides of “Athens expanding its empire,” bringing “tyranny abroad and eventually tyranny at home.” What would follow, he wondered, for a United States that had become “an incredibly imperialist nation right now, at war all over the world”?

Ratner saw no reason to change this verdict, even during the Obama years, though—thanks, in part, to his intervention—America’s wars had become less glaringly vicious in their conduct. “[Obama] doesn’t really give any way to end continuous warfare, because he never addresses the very reasons…as to why the US is in continuous warfare,” Ratner observed of the president’s public explanation of the lesser evil of the drone warfare that he had embraced. “He doesn’t talk about the fact that it’s about US hegemony, domination, control.” Obama frequently insisted that torture is not “who we are.” But what about war itself? As Ratner concluded, writing in 2013: “Yes, that’s who we are.”

Ratner died from cancer in 2016. He had lived with the knowledge that the war on terror had evolved into something different, because the very law he had helped impose made the conflict easier for others to continue sustainably. With fewer enemies captured, no one tortured, and the Guantánamo camp increasingly a shadow of its former self, the causes that lit the furnace that forged a legal war were increasingly things of the past. The war, now debugged and legalized, was developing in an ostensibly humane form, not ending. If there had been a chance to place limits on the war itself, it had been missed.

That the dictates of humane war were so soon reasserted after the Bush lawyers’ attempts to lift them from American operations was a testament to how powerful and controlling they had become. International law governing the conduct of war had once been extraordinarily permissive to the great powers that had crafted it with their global imperatives of security and rule in mind. And in those days, even when it was broken, that had not interfered with the public legitimation of war.

What had changed for Americans, by September 11, 2001, was that inhumane war had become almost impermissible, while humane war without end was now entirely viable. The few years of brutality after that date proved to be not inhumane war’s frightening return, but its last gasp for the foreseeable future. It is not to minimize the outburst of atrocity and the dubious practices in America’s ongoing wars even today to suggest that selectively attacking them has had paradoxical consequences. The decline of brutal war turned out to be intimately related to the rise of endless war.

Have the rise of Donald Trump and his move to withdraw from Afghanistan or Joe Biden’s controversial decision to see that decision through interrupted these patterns? That remains to be seen. It was notable that, for two years, Trump deployed drones and special forces even more intensively than President Obama had; under Biden, the drone policy is merely under review. As yet, however, none of the legal authority to wage war arrogated since 2001 has been relinquished.

Ratner was caught between his ultimate hopes for an America beyond war and his practical actions to make American war humane—even at the cost of perpetuating it. Twenty years and counting after September 11, 2001, so are we.