For the past twelve years, I have lived in New York’s Financial District. When I first moved in, during the crash of 2008, I listened for crowds on the street below my apartment. If I heard them, I would imagine that they were the sort of mob that surrounds the castle of a wicked lord at the end of a horror movie, ready to deliver justice while the credits roll. I was always disappointed. When I poked my head out the window I’d see a gaggle of sports fans, or just one noisy person hawking a brow wax.

I kept waiting for the pitchforks. On September 17, 2011, they finally came, in the form of Occupy Wall Street. The protest movement would change both me and the country in ways neither of us could have imagined.

Occupy Wall Street was a child of the Great Recession. In 2008, America’s largest banks had wrecked much of the world economy with an orgy of predatory lending, crazily repackaged debt, and naked fraud. Within months, some 10 million Americans lost their homes. Like many of the people who later joined Occupy, I threw my energy that year into the presidential campaign of Barack Obama. We hoped Obama would bring a change from the humiliations of the Bush era, staunch the economic misery, and end America’s murderous War on Terror. Instead, the banks got bailouts and the wars and foreclosures went on.

By 2010, popular revolts were shaking the world. In May, mass student strikes shut down the University of Puerto Rico in Rio Piedras over tuition hikes. Later that year, students with similar grievances occupied universities across the United Kingdom, and were met with police violence. Then, on December 17, a young Tunisian fruit seller named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after a police officer confiscated his cart. When he died of the burns, three weeks later, all of Tunisia joined in revolution. The country’s repressive but moribund dictator fled.

By early 2011, protests had spread throughout the Arab world—from the Maghreb to Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Yemen, and Bahrain. And with them came protest camps in city squares, which, when anti-austerity protests started in Greece and Spain, became models for their occupations. These camps grew into microcosmic societies, with clinics, soup kitchens, media centers, even libraries. Despite running the gauntlet of police batons and tear gas, many protesters viewed these improvised communities as laboratories for a leaderless, prefigurative, even utopian sort of politics. Tent cities would be the provisional wing of a better world.

Even North America, global center of neoliberalism, was not immune from the new mood sweeping the world. On July 13, 2011, the Canadian anti-consumerist magazine Adbusters asked a question that capitalized on the zeitgeist. “Are you ready for your Tahrir moment?” Beneath the hashtag #OccupyWallStreet, the editors ran a photo of a ballerina balanced atop the Wall Street Bull. She stood on pointe, one leg raised behind in an arabesque, the righteous hordes of the revolution behind her. Adbusters called for 20,000 people to flood the Financial District and set up a peaceful protest camp based on their notions of the Egyptian revolution. They made no demands.

Although Adbusters had no institutional basis in the political left, it had impeccable timing. So it was that a decade ago this week, on September 17, a first wave of two thousand people heeded the call and gathered in front of the Museum of the American Indian in Lower Manhattan. I was among them. Later that evening, a group of anarchists, including the radical anthropologist David Graeber, led about a hundred protesters to set up camp on an unlovely slab of concrete in the shadow of corporate towers called Zuccotti Park.

*

Occupy did not impress me at first. Although I’d often marched against the Iraq war, in the intervening years I had only occasionally attended protests. My friends considered it an embarrassing hobby, akin to going to dog shows, so I usually went alone, stood around awkwardly with my fellow weirdos, and eventually left. I protested the way an agnostic attends church: it would probably accomplish nothing, but one ought to do it anyway, on the chance it might matter. The first day of the Occupy action struck me in this same vein. That night, when I dropped off tarps at Zuccotti, I saw the same desultory drum circle and empty info table that marked every other futile protest scene. Tahrir Square this was not.

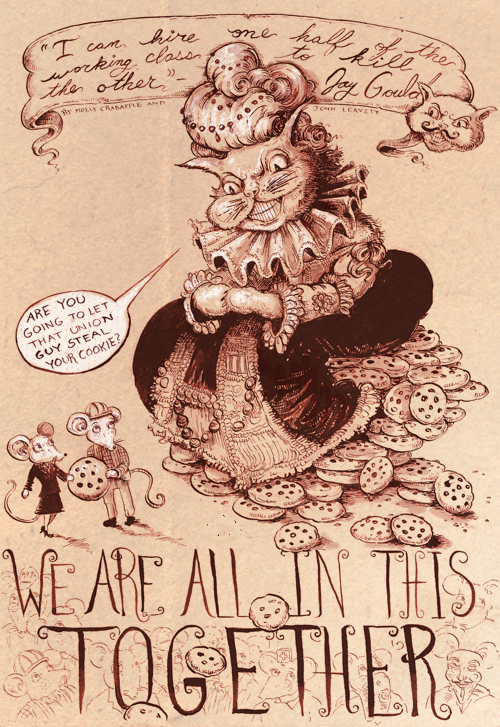

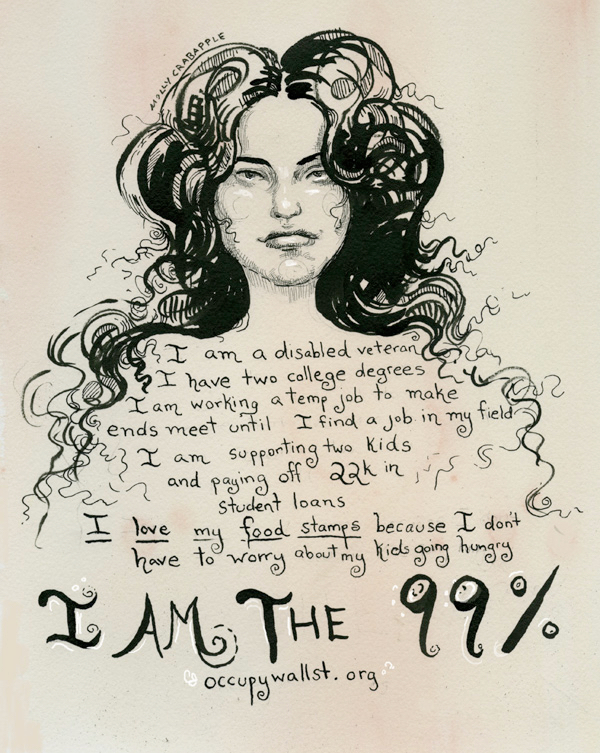

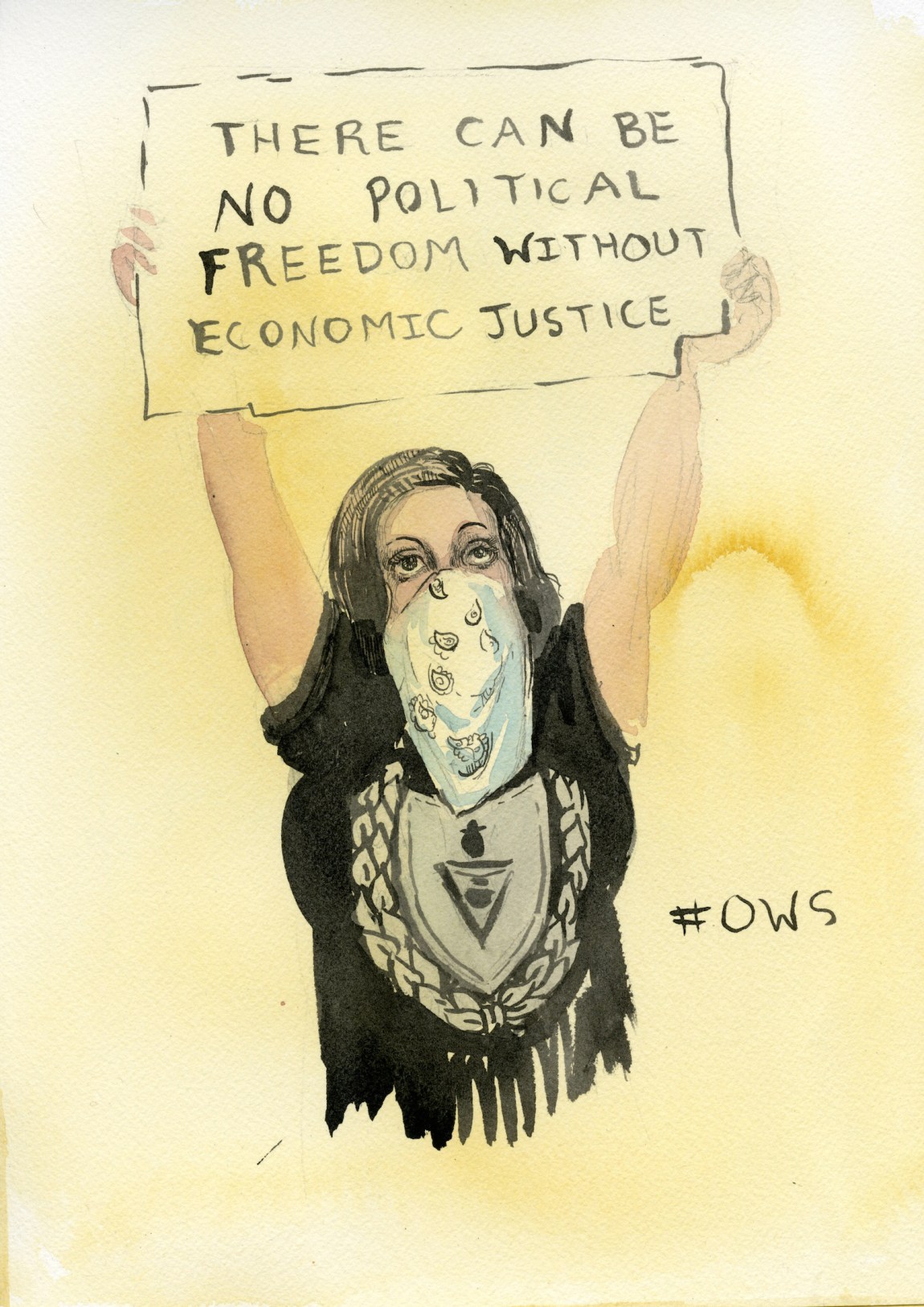

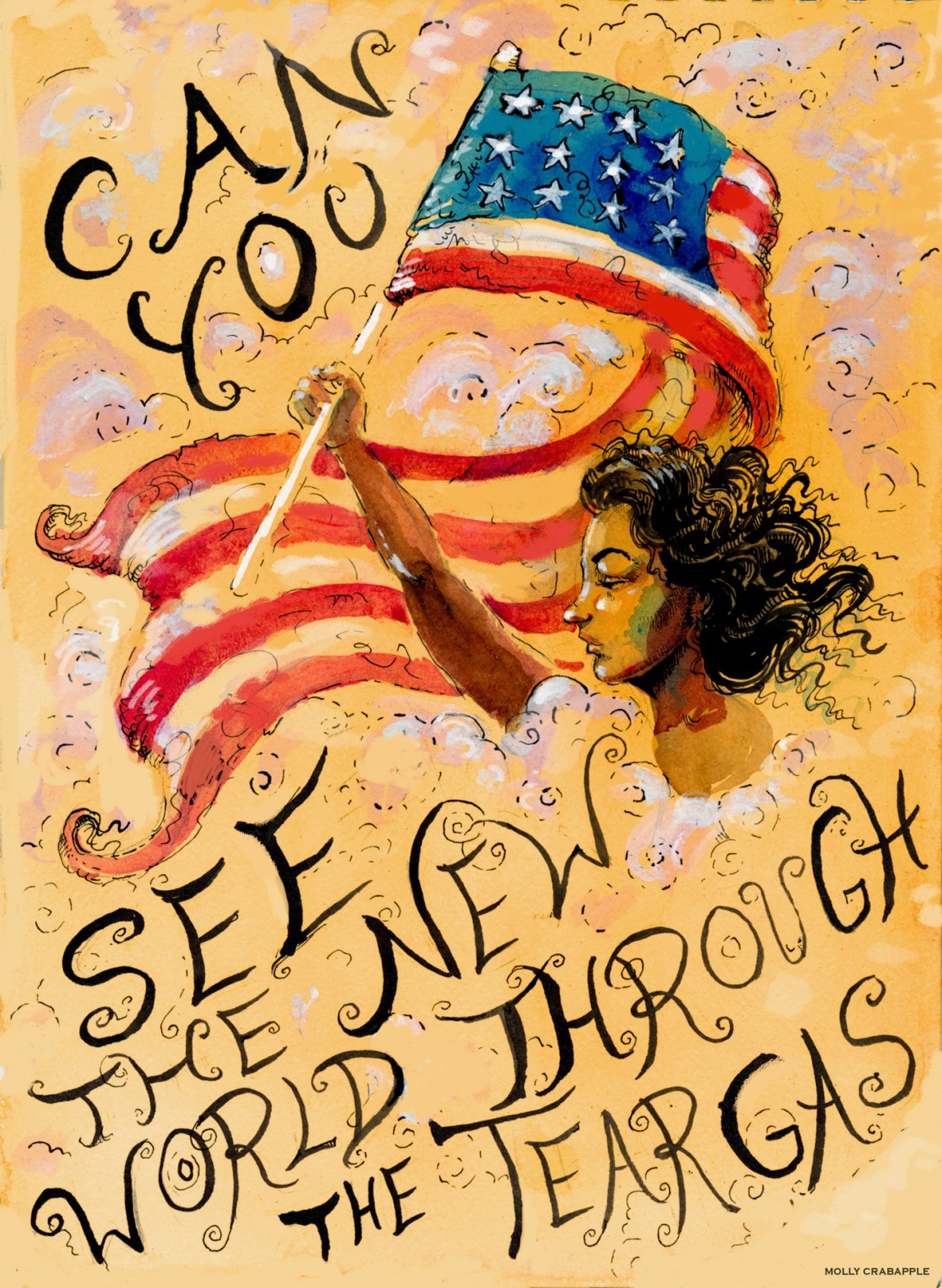

Still, I kept coming back. At first, it was just a few punks in sleeping bags, but within a week, Zuccotti Park was transforming itself into the locus for something bigger than any seasoned activist, let alone a jaded one, expected. All sorts of people—from grandmothers to Iraq war vets to junkies to disaffected finance workers, many having never participated in a protest before—started to arrive. The chants give a hint as to why. “Banks got bailed out! We got sold out!” was an anguished cry of dejection at the 2008 bailout, while the jubilant assertion of “We are the 99 percent” welcomed everyone except the ultrarich. Each day, hundreds of people marched out of the square shouting these words—to be kettled, clubbed, and pepper-sprayed by the New York police. Every police attack was filmed on camera phones and uploaded to social media, where they served as an advertisement to bring more people to Zuccotti Park.

Advertisement

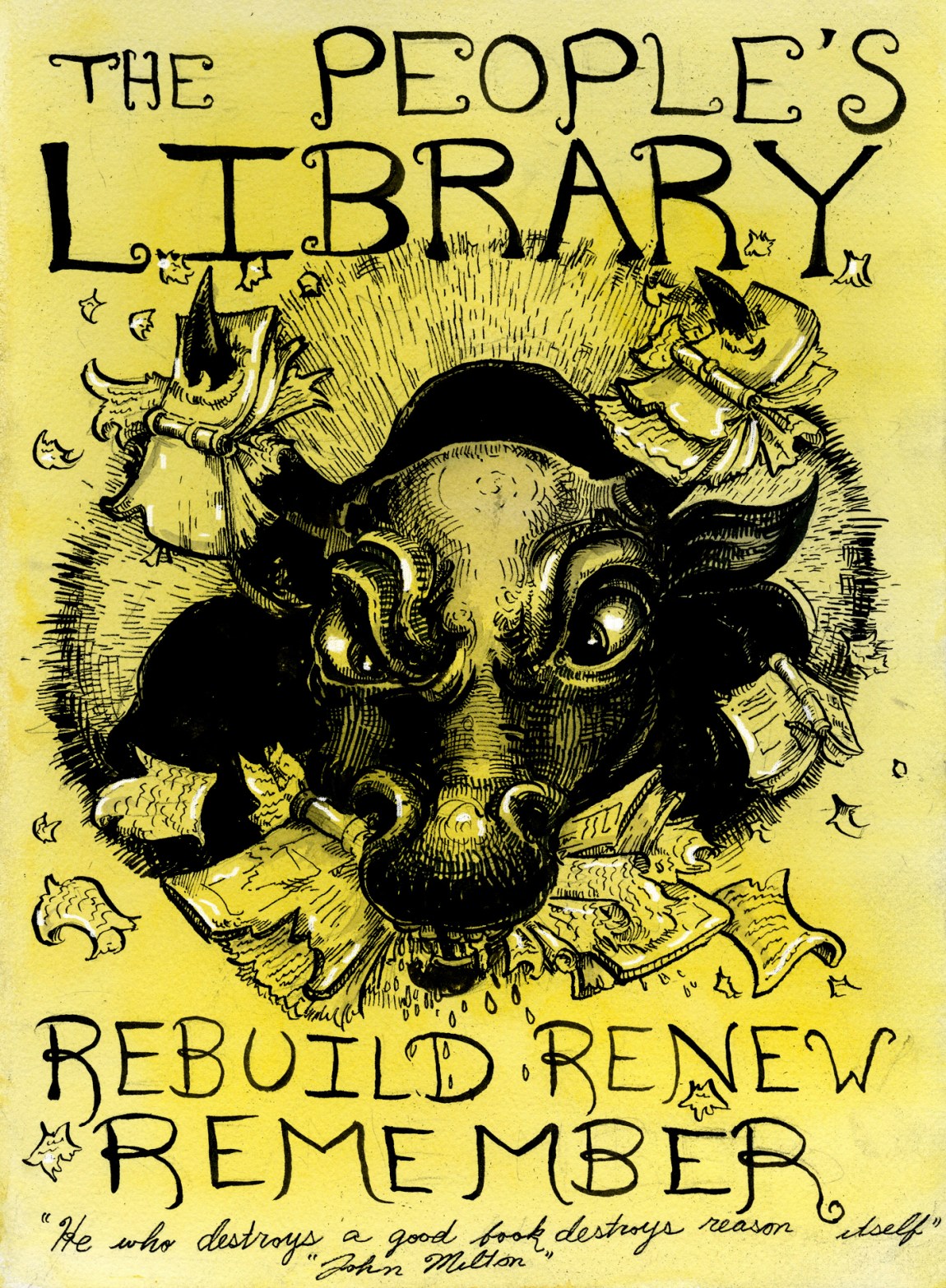

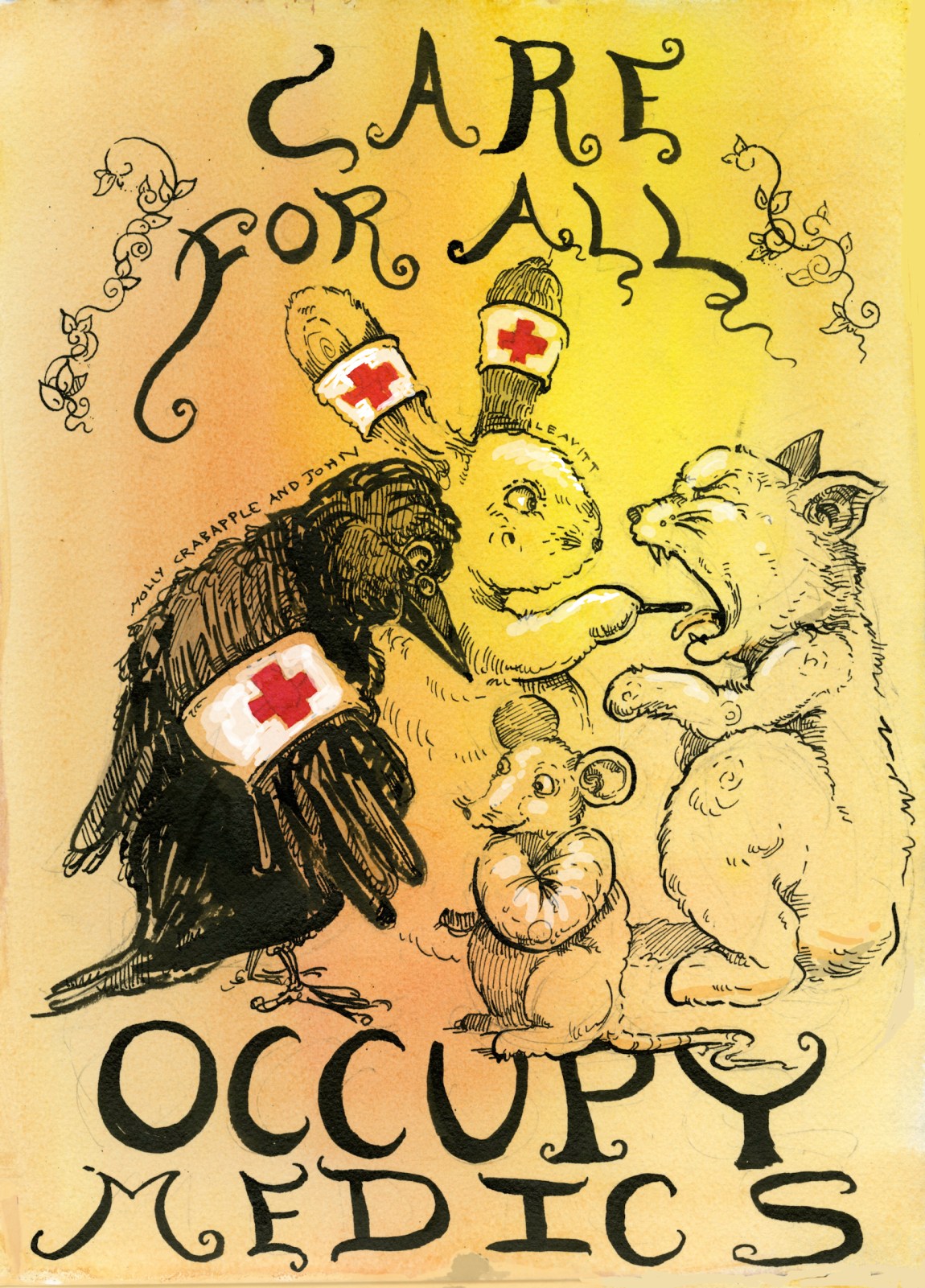

The park had quickly evolved into another island in the long archipelago of world protest—it too had the clinic, the library, the kitchen, and the media tent with its tangle of wires. Not only that, but it was inspiring other Occupy encampments to spring up across the country and on other continents. Activists from its forebears in Egypt and Spain came visiting. Famous writers delivered open-air lectures. Punks gave out hand-rolled cigarettes.

Above all, Occupy was participatory. Anyone could join, just by turning up. There were assemblies where, because of a ban on amplification in the park, the audience repeated back each of the speaker’s phrases (a technique known as “the People’s Mic”). But because of the unwieldly nature of decision-making at these endless, open meetings, far more was accomplished by smaller groups of people acting on their own initiative.

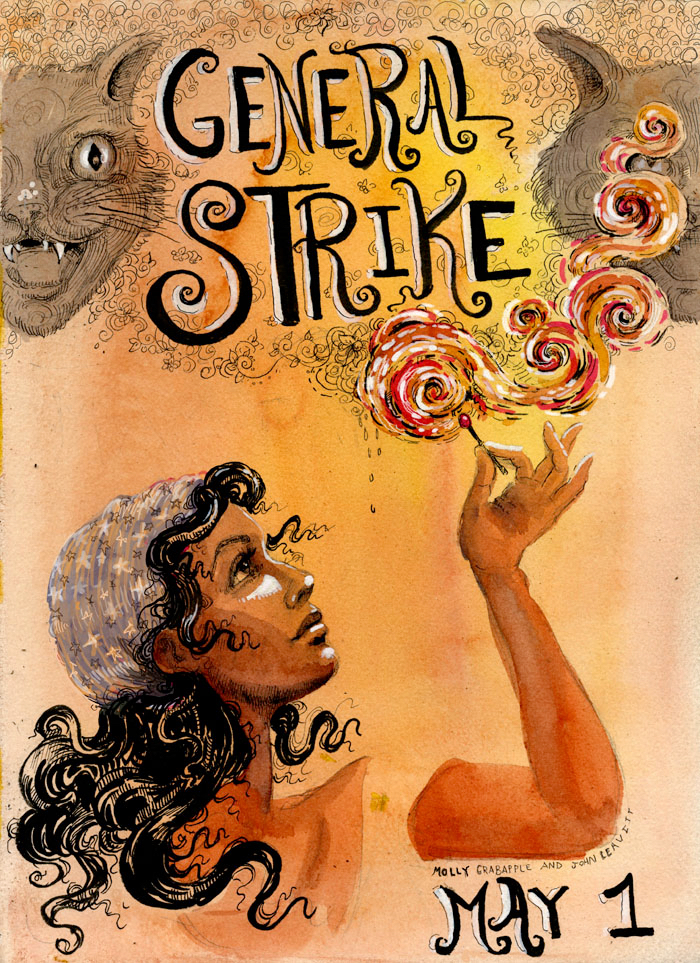

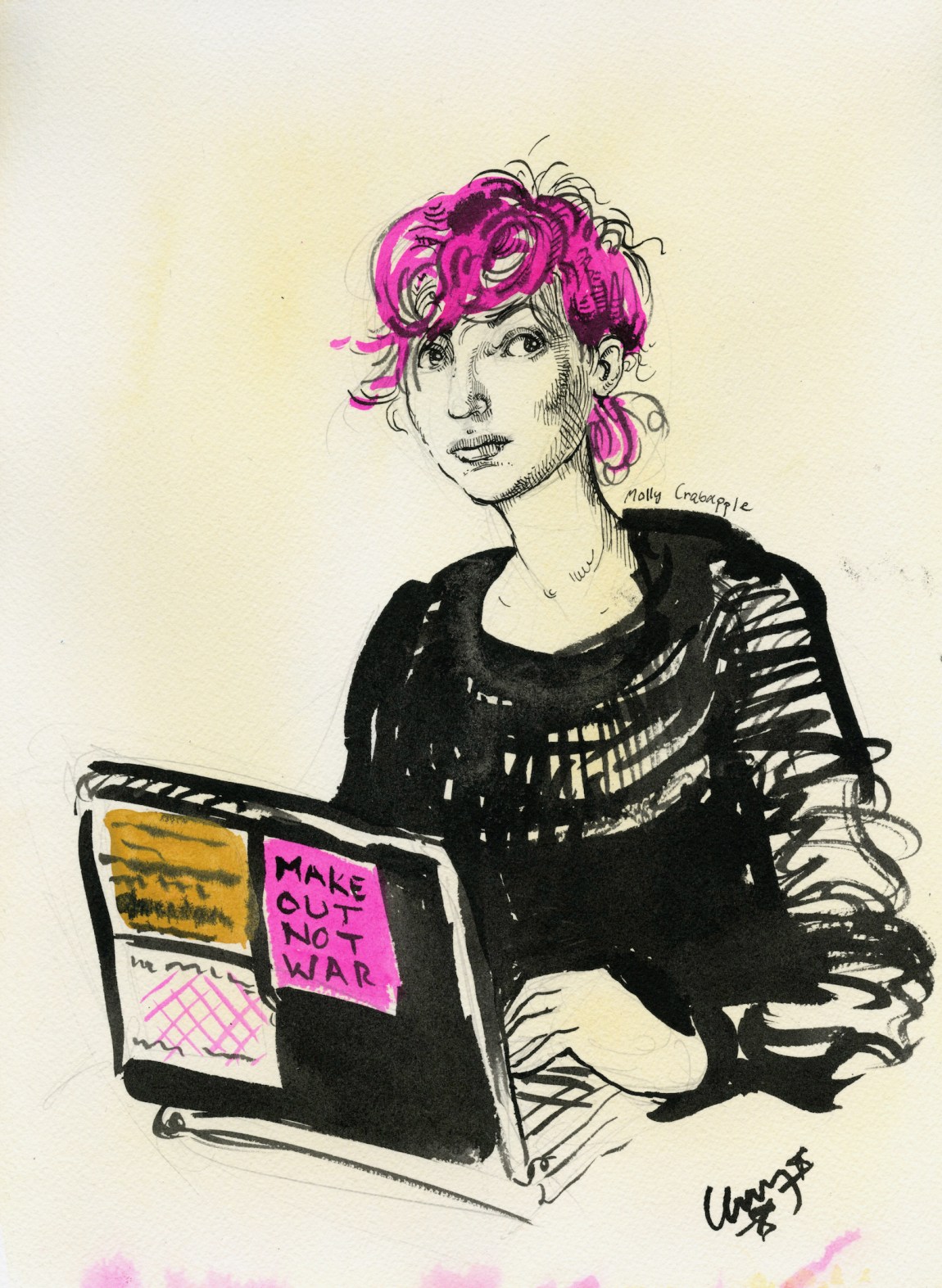

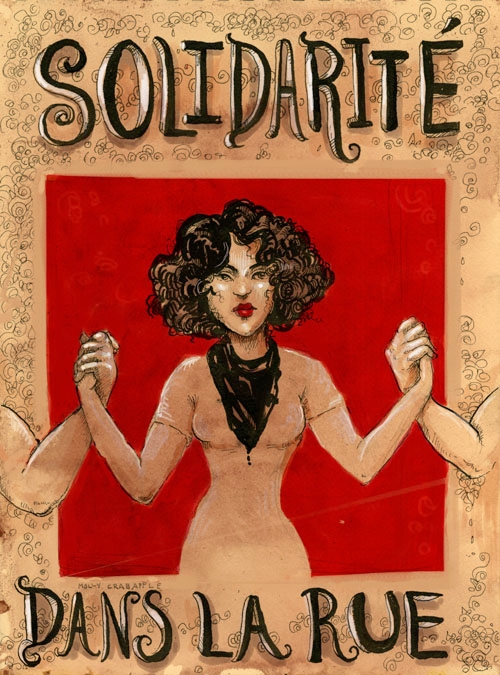

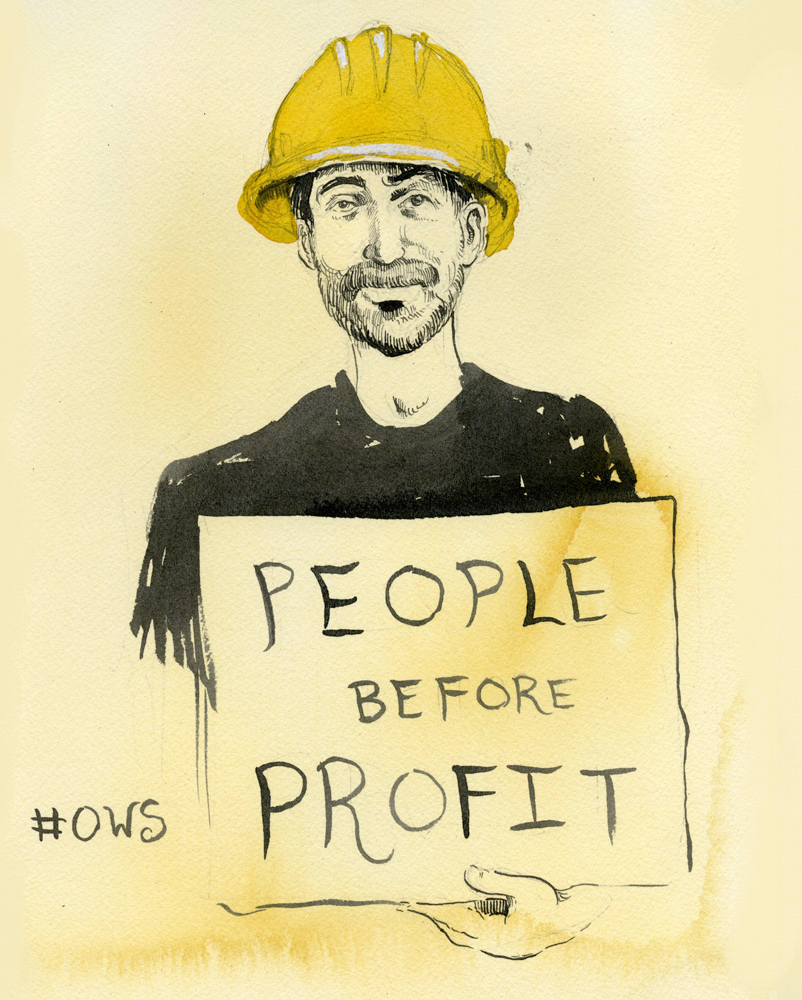

I began drawing the protesters. But soon, I was participating. I sold art prints to raise money for bail funds and created protest posters. I sent these as scans to organizers; within hours, they were on the street. Since my apartment was just down the block, I offered it as an impromptu pressroom, and the floor of my living room filled up with journalists who drank my coffee while filing their copy. And by spending so much time around them, I slowly learned to write.

Responsible citizens did not like Occupy. At a moment when cops were gleefully cracking skulls, Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show devoted an entire segment to mocking the occupiers. We were stupid, dirty hippies, most of the media said. We had iPhones and drank lattes, like hypocrites. We knew nothing. We didn’t want to work. We did not participate sufficiently in electoral politics. We did not make proper demands.

The last part was only partially true. Occupy did not have a PowerPoint of action items, but anyone who went down to Zuccotti Park would have found demands aplenty. They ranged from calls for specific policies, such as the reinstatement of the Glass‑Steagall Act and the overturn of Citizens United, to the goal of debt forgiveness, to cries for bankers’ arrests. It depended on whom you spoke to. But what united occupiers was a well-founded belief that the US government served only the 1 percent, a corrupt and rapacious elite, and not the other 99 percent of the country—a belief reinforced by every police barricade that ringed that tiny park.

Zuccotti Park came to enchant me. I think back to the hurry of meetings, the scramble from protest to jail support, the rush to draw something fast enough to meet the deadline for a newspaper published out of the park, the long hours on fire escapes with those people who remain my tightest friends, talking as if we could figure it all out, right then and there. I remember the ferocious solidarity with strangers, as if we would do anything for one another, as long as we were all shoved shoulder-to-shoulder on the wrong side of a barricade. I would sit in the park late into the night, and read a book from the People’s Library while a violinist played. Sometimes, in the unseasonable warmth that fall, I could feel the possibilities of a new world stirring, out of all proportion with the smallness of my actions.

I have talked to many veterans of protest camps, whether in 2011 New York, Greece, Egypt, or, later, in 2013, in Turkey’s Gezi Park. All speak about them as the most beautiful events of their lives, though those movements were bludgeoned into silence. To those who have never felt it, this romance is the hardest to convey. For outsiders, the transience of these movements is too apparent, their failures too pre-ordained. And yet, any account of the Occupy experience is fundamentally dishonest if it does not mention this love.

Romance, combined with stubbornness, powered Occupy into October, when winter came early and coated the streets with gray, dispiriting slush. The police seized the generators brought in to heat the park. By then, they had arrested hundreds of protesters. They beat Black occupiers with a particular viciousness. They attacked journalists. Across the country, police and the FBI had many of the hundreds of Occupy encampments under surveillance as potential terrorist threats. In Oakland, police shot a bean-bag round that hit a veteran named Scott Olsen in the head, putting him in a coma.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, the assemblies, as tends to happen, devolved into factional recrimination. But when then Mayor Michael Bloomberg threatened to evict campers from the park on October 14, in the name of public hygiene, a group of sympathizers, including union members and journalists, converged that night on that frozen square of concrete and cleaned it until it shined, all under the eyes of the police. When the sun finally rose, Mayor Bloomberg blinked. The cops did not charge. Even if the occupiers had no idea what winning might look like, that morning felt like a victory.

One month later, just after midnight, police sealed off Lower Manhattan and destroyed the Occupy Wall Street encampment. They arrested seventy people, tore up the tents, threw the books of the People’s Library into dump trucks, and punched in the face any journalists who tried to get too close. Afterward, it would never be the same. The marches continued, with attempts to take this little park and that. The police routed us each time. They corralled us with barricades. Protesters screamed they were not afraid. On St. Patrick’s Day, 2012, an undercover cop stood behind a young protester named Cecily McMillan and grabbed her breast. She elbowed him instinctually. Wading in, cops beat her until she had a seizure. Cecily was charged with assaulting an officer and spent fifty-eight days on Rikers Island.

My turn came on Occupy’s first birthday, September 17, 2012, when a police officer pulled me into the street and then arrested me for blocking traffic. It was my first arrest, and not a bad one as far as arrests go: eleven hours in a holding cell; no cops hit me. It is a salutary experience for anyone with white skin and a middle-class upbringing to spend a day confined in an stinking cage, where they are treated with the slack-jawed contempt that police so excel in. After all, this is how America treats its poor, Black, and Latino inhabitants daily. Following the arrest, I wrote an account of the encounter in an article that was published in CNN, setting me on course to becoming a journalist. By then, though, even I knew that Occupy was dead.

*

Such was the fate of every beautiful uprising of 2011. Each was outflanked, outlasted, or bloodily crushed. Bahrain put down its rebellion with the help of Saudi tanks. Egypt’s finest activists rot in the jail cells of their military dictatorship. Syria became a charnel house, and Yemen the worst humanitarian crisis on earth. Even Tunisia, the Arab Spring’s only success story, recently suffered a coup. In Europe, the consequences were milder, but the defeats still real. Students in the UK lost their fight against austerity. The EU kept its fiscal pressure on Greece, a country now led by the Harvard-educated hard-right of the New Democracy Party. In Spain, the third-largest political party in parliament is the fascist Vox.

Most uprisings fail, of course, if overthrow of a regime is the measure, and governments are sturdier machines than protesters give them credit for. Protest camps are no match for the armed force of the state, as in Egypt, let alone aerial bombardment, as in Syria. In Occupy’s case, though, despite the police repression it faced, I blame its failure on the movement’s amorphous, leaderless nature as well. In an essay written in the summer of 2019, after mass protests brought down Puerto Rico’s governor, Ricardo Rosselló, the socialist intellectual Rafael Bernabe celebrated the uprising, but warned of the dangers of “anti-politics”: a worship of seemingly spontaneous mass action that leads people to discount the importance of coordinating structures and of political programs, and to dismiss electoral politics as always suspect and tainted. Without these, the same old scoundrels stay in power forever.

I agree. Occupy grew fast, but it was not solid. Its strengths were also its weaknesses. The openness allowed certain grifters to ride its fame all the way to Davos. Its wild creativity let independent projects use Occupy’s name and then collapse into unfathomable disorder. General assemblies gave many people their first opportunity to be heard in a democratic forum, but they often went in circles until only the most infuriating participants remained. The lack of an agreed list of demands meant there was no way to know if the movement had won anything. Without practical gains, most people ended up drifting back into their regular lives—assuming regular lives were still an option for them.

And yet. Many were too eager to bury Occupy without praising it. Many projects that came out of Zuccotti still reverberate today. When Hurricane Sandy devastated parts of New York in October 2012, Occupy volunteers were there to clean up the wreckage. Across the country, Occupy Our Homes activists continued to defend hundreds of homeowners from foreclosure. Both actions prefigure the mutual aid and anti-eviction defense efforts we see today. Occupy veterans such as Astra Taylor established the Rolling Jubilee, an organization that to date has bought and forgiven more than $31 million of personal debt—an initiative that has since been copied by John Oliver.

Even greater was the change Occupy wrought to the larger culture. With its slogan “We are the 99 percent,” Occupy shattered the American taboo against talking about class. It made Americans see that their poverty came not from their own stupidity or weakness, as they’d always been told, but was the result of a system rigged for the benefit of a very few. And it showed them that the system could be contested. Occupy spoke plainly about class conflict, in a way that opened the door for the presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders—as historic in their way as they’d once have seemed improbable.

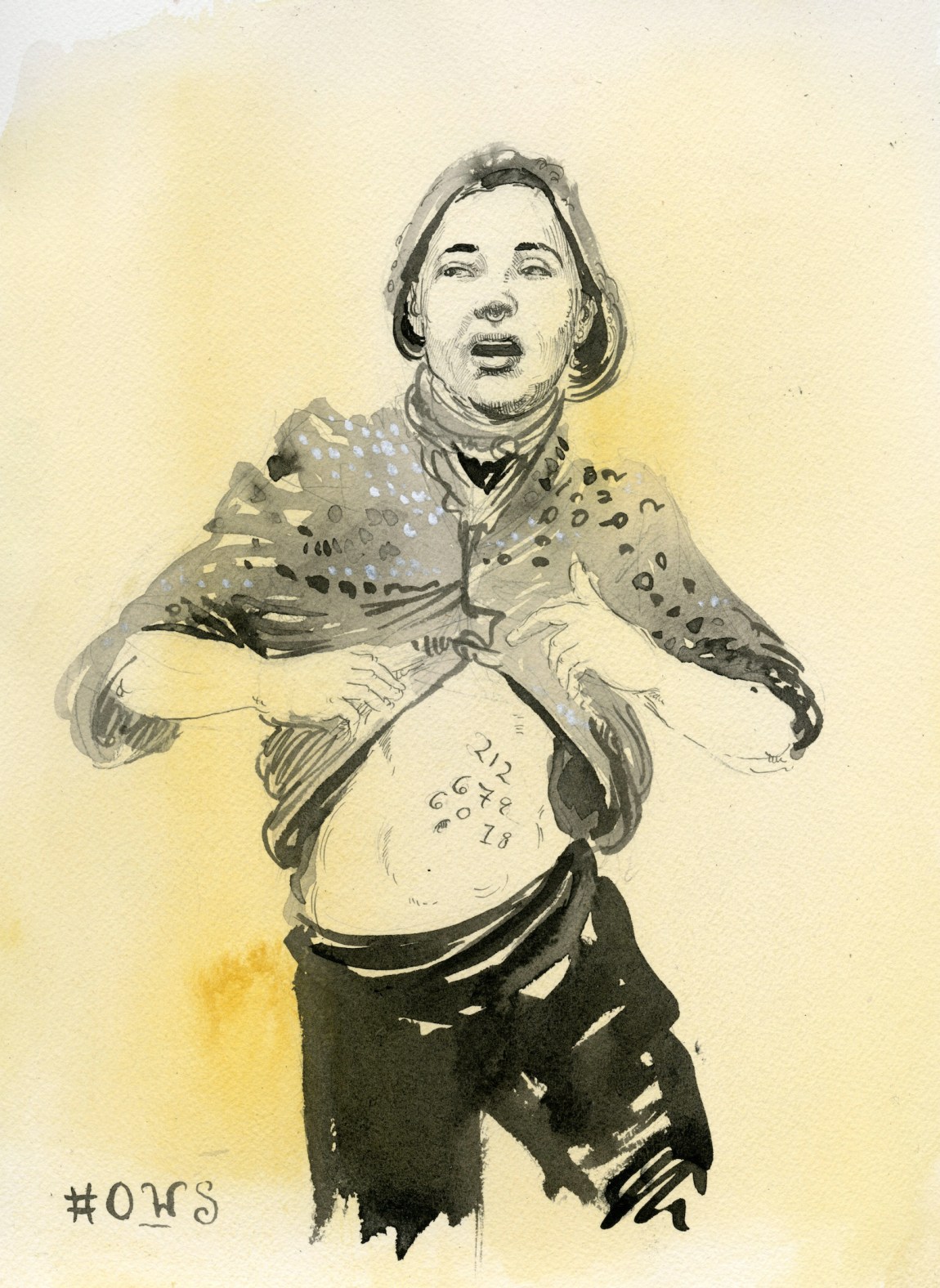

Lastly, there is the alchemy a movement works upon its participants. Occupy may be dead, but occupiers are very much alive. Occupy taught thousands of people the tactics of protest: to write the Lawyers Guild phone number on their stomachs, to pour milk in their eyes after they’ve been pepper-sprayed, to use their bodies to shut down an overpass, to say nothing to the police. It taught them grit, courage, and skepticism of authority. Those people did not go away.

In 2014, after a white police officer named Darren Wilson murdered a Black teenager named Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, antiracist protests broke out across the country; in New York, my friends from Occupy were on the streets. I hesitate to compare the Movement for Black Lives to Occupy Wall Street: with the former, there is no shortage of demands, or of leaders; its protesters are braver and more militant, and the crackdowns they face far more extreme. But there is some enduring kinship between the two movements.

One night of that hot 2020 summer that followed the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, I sat in New York’s City Hall Park, which had been taken over by a new protest camp. #OccupyCityHall began as an action by Black activists in progressive nonprofits—though they soon struggled for control of it with numerous young, unaffiliated, mostly Black and brown protesters. For me, it could not but evoke memories of the long-lost #OccupyWallStreet. Over several weeks, I stopped by every day to clean, deliver home-cooked meals, or just to hang out with other people after those miserable months of the pandemic lockdown.

At Occupy City Hall, there was the familiar infrastructure—of media tents, libraries, clinics, free stores, and kitchens (albeit better done)—and much of the park was given over to the artistic memorialization of Black people killed by the cops. The nonprofits did have a demand: to cut a billon dollars from the police budget. Many protesters called more ambitiously for the police to be abolished. Finally, the City Council voted on its budget. A billion dollars were not cut. A few nights later, the nonprofits pulled out. The cops were, as ever, primed for attack.

I watched this new generation of protesters build barricades out of the city’s detritus. Behind the barricades, bikers arranged their bikes like shields. Then came rows of young people with locked arms, wearing hard hats and goggles. Behind the frail safety of these defenses, silhouetted against graffiti-covered statues, the entire park seemed to be dancing. And why not? They were young and beautiful and had just survived a season of plague. By the next summer, a centrist Democrat, a former police officer who ran on a platform of law and order, would win the primary to become the next mayor of New York, but that night belonged to the protesters once more. “Whose streets? Our streets!”

Beyond the cultural successes and practical failures of Occupy Wall Street, and the arguments about what its legacy has been, I think back to this one, simple demand. These streets on which we stand are not private property, the preserve of the wealthy, mere arteries for conspicuous consumption, patrolled by their goons. They are ours, they are the public square that belongs to all of us. And that goes for the country, too.