Two poles of Todd Haynes’s documentary film on the Velvet Underground, a band—Lou Reed, principal singer and guitar; John Cale, viola and other instruments; Sterling Morrison, guitar; Maureen “Moe” Tucker, drums—that formed in New York City in 1965, came under the sway of Andy Warhol and the denizens of his Factory, released its first album, The Velvet Underground and Nico, in huge letters “PRODUCED BY ANDY WARHOL,” in 1967, its fourth and last, Loaded, in 1970, and disbanded that year, after Cale had already been excluded from the group in 1968:

One pole is John Cale, first shown in footage of a 1963 episode of the CBS quiz show I’ve Got a Secret. His secret was that he was one of eleven musicians to take part in an eighteen-hour, eight-hundred-and-forty-part performance of Erik Satie’s Vexations (with him on the show was Karl Schenzer, whose secret was that he sat through it). He speaks now about composing with the sound artist and critic Tony Conrad in an apartment on Ludlow Street in the Lower East Side that Conrad (“I didn’t want to be part of the economy”) rented for $22.44 a month: “The most stable thing we could tune to was the sixty-cycle hum of the refrigerator. Because to us, the sixty-cycle hum was the drone of Western civilization.” On Haynes’s split screen: Cale himself, a view of New York pedestrians as seen from above crossing the street in a diagonal pattern, cars, apartment buildings, telephone poles, tall buildings.

The second pole is Lou Reed, who has been heard early in the documentary on the music that most inspired him as a boy growing up on Long Island—rockabilly and especially doo-wop, or street-corner group harmony (“The sounds of another life,” he said in 1989, inducting the Bronx singer Dion into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, “the sounds of freedom”)—and on making his first record, a doo-wop ballad, at fourteen, having it played on the radio (he received a royalty check for $2.79, more, he says, than he ever made from the Velvet Underground). Here he is speaking over a neatly typed lyric sheet for his song “Heroin,” which appeared as the first song on the second side of The Velvet Underground and Nico. As framed on the screen, the lyric sheet looks more like a grid, with two lines partially crossed out and new words scribbled over them: “I was writing about pain. Reality as I knew it. Friends of mine, things they had seen, things I had seen, or heard. I was interested in communicating to people who were on the outside.”

*

Jean-Luc Godard, in his review of Bitter Victory in Cahiers du cinéma, January 1958: “There was theater (Griffith), poetry (Murnau), painting (Rossellini), dance (Eisenstein), music (Renoir). Henceforth, there is cinema. And the cinema is Nicholas Ray.” With a little absolutism scraped off, and without excluding anybody else, the same could be said of Todd Haynes. He thinks in movies—not in terms of knowing everything in the history of the movies and how to put it to use, but as a way of seeing, and transforming, the world. From the start, in 1987, with Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, the notoriously and, less often noted, overwhelmingly moving film staged and acted out solely with Barbie dolls, he celebrated the fact that a real movie could be made out of anything. His eye is so drawn to detail, and his direction so open, that in his strongest work you can’t see everything on the screen at once: not in the New Age healing drama Safe (1995); the drama of postwar racism and homophobia in the suburbs, Far from Heaven (2002) (as one writer put it, even the leaves on the trees look as if they’re from the Fifties); I’m Not There (2007), in which fictionalized portraits of Bob Dylan are played by six or seven different actors, including an African-American boy and one or two women, depending on how you see it; and, most entrancingly, not in Wonderstruck (2017), in which an entire narrative sequence is (to save money? Just for fun? To make an argument about storytelling?) animated in miniature and enacted by figurines, and so vividly you barely notice they’re not actors. You can go back to his movies years after first seeing them and feel as though you’ve never seen them before, because you notice so much you didn’t see the first time. Not because details were hidden, or masked in some kind of code you’ve now deciphered, but because, in Haynes’s pictures, life is plainly that shaded, language is by nature always incomplete and cryptic, and a story well made, playing out in the imagination of the viewer, is never really over.

In that sense, all of Haynes’s previous films can feel like a warm-up to Velvet Underground. Here there is nothing that doesn’t feel it’s not part of his ordinary cinematic speech: his own filmed interviews with those still living (Sterling Morrison died in 1995, Lou Reed in 2013), archival interviews used as voice-overs, performance footage of everyone from the Velvet Underground to the Everly Brothers, bits of gay porn movies, sequences from the anthropologist and idiosyncratic record collector Harry Smith’s 1950s painted-frame films and his 1962 all-manipulated-image-objects movie Heaven and Earth Magic, Andy Warhol screen tests, footage from Warhol’s Factory, abstract designs and frames with dancing lines, still photos fixed and panned, stock footage, and dozens if not hundreds of other sorts of images, usually presented in double or triple or quadruple split screens. At one point, to illustrate the avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas’s celebration of the cross-cultural ferment of “the Sixties”—here an idea more than a period, a time not an era—Mekas’s Gesamtkunstwerk-in-the-streets appears across twelve split screens in a montage of faces, galleries that keep changing to the point that you want to stop the movie to see who everyone is, even if, even then, you will probably never find out.

Even more memorable—something that could not appear in any ordinary documentary—is a composition. With John Cale on the left in his Warhol screen test, describing his cold childhood in Wales, on the right is a changing constructed image. His mother has breast cancer; she’s taken to an “isolation hospital.” Haynes shows us a black-and-white still of what looks like a windowless stone prison on a high hill, a place no one ever leaves, not even the people who work there—with a little Giorgio de Chirico train painted red running across the bottom of the image from right to left. “She vanished,” Cale says. In what could be two seconds from a horror movie, or some kind of training film, a woman’s face appears and falls out of the frame.

That is the sort of weight the film can carry, that it can enact. And there are equally strong juxtapositions that are more deeply effective as narrative than the almost always interesting scene-setting from talking heads. Following Cale playing Vexations—once—on I’ve Got a Secret, Lou Reed appears in his screen test (hold still, don’t blink, don’t sigh, be a still) on the right, while on the left there’s footage of a family gathered by the radio, Fifties record stores, a sped-up Chubby Checker dancing on a piano, rock ’n’ roll crowds—but it’s the soundtrack that makes the real counterpoint. As Reed describes his first music lessons, his first musical loves, you hear “The Wind” by Nolan Strong and the Diablos, from Detroit in 1954, the most ethereal doo-wop record ever made. It is wind—and immediately you can grasp the affinity between 1950s doo-wop and the abstractions of twentieth-century avant-garde composition. The same thing happens when Haynes, coming off a sequence on the Warhol films Kiss (1963) and Empire (1964), and Tony Conrad describing his rock ’n’ roll record-collecting fetish (“I was dazzled by the pure harmonies”), puts Bo Diddley on the screen: the master himself, with his deadpan sister, Lucille McDaniel, on guitar and a ducktailed blond bass player in a sweater who looks like a refugee from a college glee club, roaring through “Road Runner” in about 1959. It sounds just like the Velvet Underground at its most daring, and you realize that as an experimental medium, rock ’n’ roll was years ahead of anything coming out of the Factory or downtown New York: that the drone Cale was pursuing was already there in “Road Runner.” It’s a thrill to see Haynes put that truth on the screen.

*

The Velvet Underground became a legend because on record they made, and on stage acted out, music that was, and remains, irreducibly heedless, corrosive, and convulsive—with “Heroin,” “White Light/White Heat,” “Sister Ray,” “What Goes On,” as it played out in performance, and a few more—the most successfully communicative and consciously extreme music of the postwar period, which is to say, the last seventy-five years. Part of that legend was the embrace of self-destruction as a means of salvation—as deliverance from the inevitable destruction of the soul by a world of—as New Order, one of thousands of bands unthinkable without the Velvet Underground, titled an album in 1983—power, corruption, and lies. Todd Haynes’s film at once illustrates and dances around questions of Lou Reed’s homosexuality, shock treatment, and heroin use, both because, in the course of his life, Reed said a thousand contradictory things on any subject any interviewer chose to bring up, and because Haynes is more interested, visually, musically, and intellectually, in questions than answers, as maybe Reed was, too. “I’ve had some strange experiences since returning to ny, sick but strange and fascinating and even, sometimes ultimately revealing, healing and helpful,” he wrote in late 1964 or early 1965 to Delmore Schwartz, Reed’s teacher, friend, and idol when Reed was in college at Syracuse in the early Sixties. Reed was working as a contract songwriter for the budget label Pickwick, cranking out genre tunes for budget albums of hot-rod and surf music and the like. He went on:

Advertisement

The record industry is as vicious as most businesses, but this one is a little more so. ny has so many sad, sick people and I have a knack for meeting them. They drag you down with them. If you’re weak ny has many outlets. I can’t resist peering, probing, sometimes participating, othertimes going right to the edge before sidestepping. Finding viciousness in yourself and that fantastic killer urge and worse having the opportunity presented before you is certainly interesting. Interesting is not the word.

Haynes lets Shelly Corwin, Reed’s college girlfriend, tell the same story with a sharper edge: the artist as observer, witness, and thug. First, Alan Hyman, one of Reed’s bandmates at college, talks about the gay themes—“Really dark gay themes”—in the poems Reed was writing while studying with Schwartz, and that Schwartz had gotten published in the Evergreen Review, the leading site for younger Beat writers. There’s a clip from Kenneth Anger’s 1963 film Scorpio Rising of a louche man lounging against a wall covered with pictures of James Dean, porn footage of a man maybe being raped or maybe taking part in a gay gang bang, and then Corwin, on the screen, talking about Reed’s taking her to a gay bar, trying to make her dance with women as he looked for men, about her being neither offended or even that uncomfortable. As if to raise the stakes, to see what her limits are, Reed takes her to an apartment on 125th Street and St. Nicholas, presumably to buy heroin: “He liked taking me to a place that was not safe. And he was just setting up a scenario that then he would have something to write about.” That and a drone led to music people had never heard before. “I knew that we had a way of doing something in rock ’n’ roll that nobody else had ever done,” John Cale reflects—in his talking head interviews throughout the film, he is engaging, funny, reflective—laughing quietly, his words serious and final. “And all that had to do with detuned guitars, that I was really proud of because I’d say, ‘Hey, Lou, nobody’s going to be able to figure out how the hell to do this.’” You can feel the pleasure of the moment, then, and now.

*

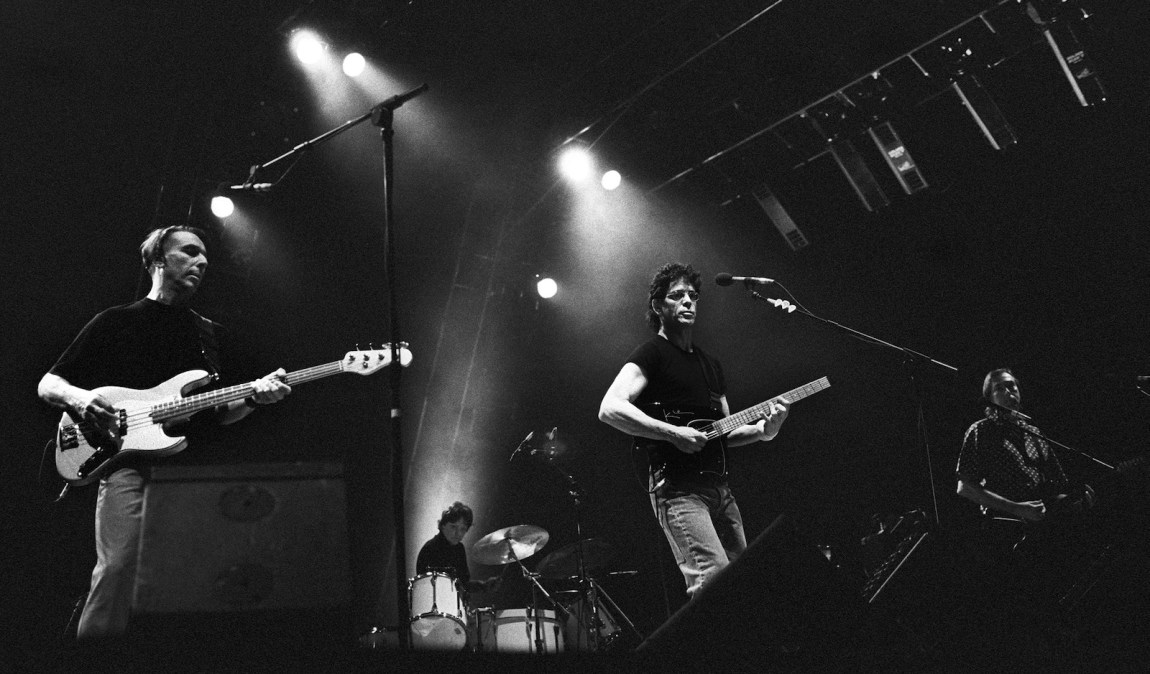

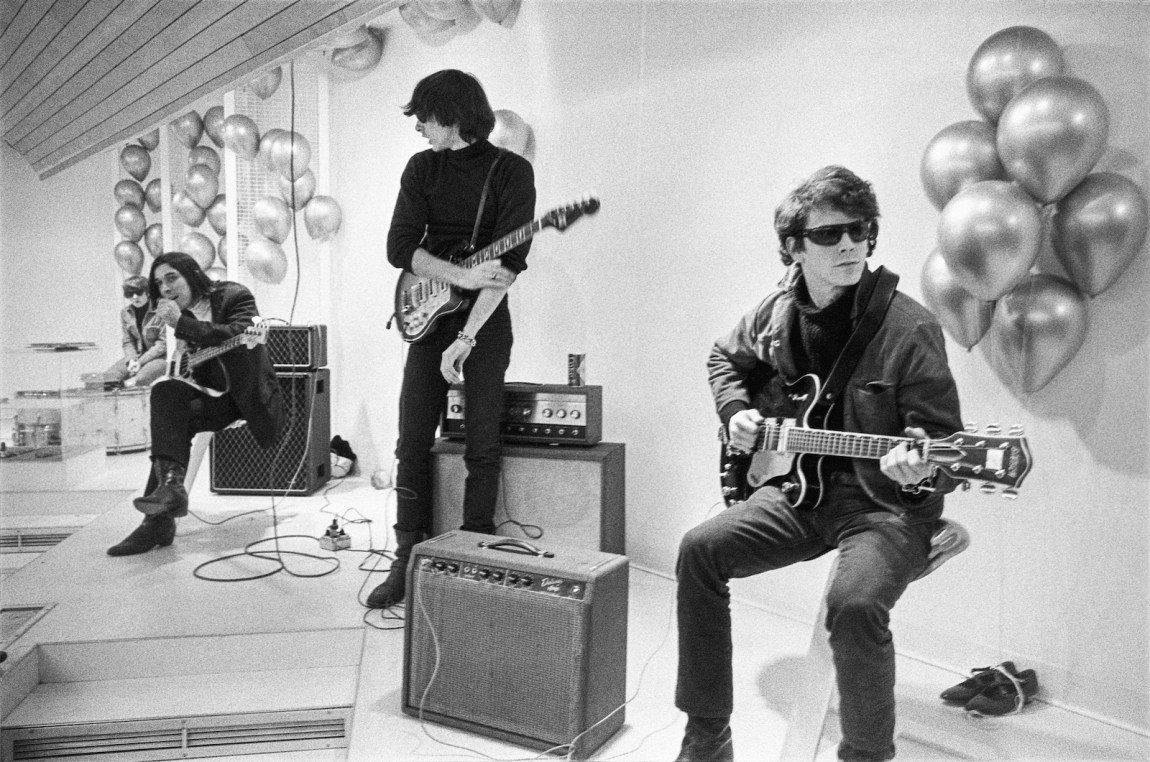

Haynes shows the band forming. Fame in the art world (their first tour was of galleries, Moe Tucker says mordantly: “We were the exhibit”). The German actress and singer Nico (who died in 1988), brought in because Warhol’s aide-de-camp, Gerard Malanga, thought the band needed something exotic to go with its unsmiling faces. So blond and icy you can imagine her in an SS uniform in a Nazi porn film, she brought a deep-voiced, drown-in-my-eyes allure to “I’ll Be Your Mirror” and “All Tomorrow’s Parties,” but it was also like making Leni Riefenstahl part of the group. The rush of the first album and, with Nico gone, the far more harsh and explicit noise of the 1968 White Light/White Heat. Reed’s firing Warhol as the band’s manager and then firing Cale. Reed’s bringing in another guitar player and singer, Doug Yule, who looked like a Monkee. The once intimidating ensemble—the men in wraparound dark glasses, looking like hit men; Tucker just as scarily impassive, sitting behind her small drum kit and methodically bringing her mallets down—now posing in smiles and paisley shirts. The implosion of the band, not from enormous success but because the music had lost its difference, its reason for being, after four years still playing the same clubs, to the same audiences. The reunion tour in 1993, in Europe and the UK nearly a quarter-century later. Out of all that, Haynes’s greatest challenge was to avoid the pull of Behind the Music, that magically addictive VH1 story-of-the-band series from the 1990s, the most formulaic show in the history of television—even on Wheel of Fortune, you didn’t know exactly where the numbers would fall or when. Every story was the same, every real-life adventure followed the same script—rise, fall, redemption—to the point that, watching one episode after another all night, it became hard to imagine any other story. Hayne escapes out of his own love of what can go on a screen, his inventiveness, his trust in the audience. He does so most strongly by focus—in the way he makes the story revolve around one song.

“Heroin” is the testimony of someone who has made a decision for addiction and death. The song is sardonic and bitter—“And I guess that I just don’t know,” is the repeating line, which really means “And I guess that you just don’t know.” Its imagery is florid and stirring—a little boy dreaming of clipper ships—and its phrasing has become part of the language, because it seems to make its own truth: “When I’m rushing, on my run/And I feel just like Jesus’ son.” Does Denis Johnson’s book of stories that took that final phrase as its title even begin to speak without that kick from Reed into his heavenly wasteland?

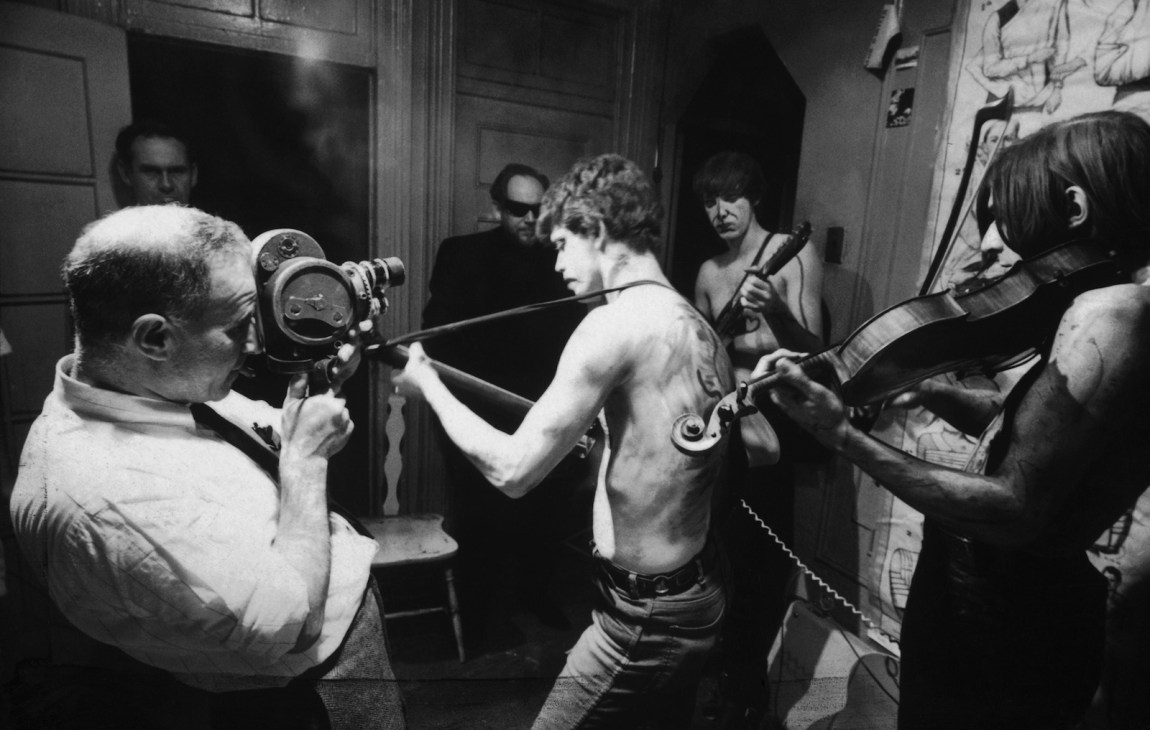

Near the end of the song, Cale’s electric viola and Reed’s and Morrison’s guitars throw up a cross fire of noise that builds on itself until any sense of individual or even collective agency burns up. The music seems to be making itself, a nihilistic manifesto that enacts in sound what Reed has already sung in words: “I’m going to nullify my life.” We first hear it about a quarter of the way through the movie, Reed reading it as a poem under his screen test—in which he blinks, then turns his head to the side, mug-shot style. Then there is the typescript. And then there is the Factory. In late 1965, the filmmaker Barbara Rubin brought Warhol to see the band play; Gerard Malanga—in Cale’s words “the diplomatic face of the Factory”—invited them over the next day.

At fifty-three minutes into the film, “Heroin,” as the Velvet Underground would record it, begins. It seems unlikely that many people who’ve never heard the song would watch a movie about the Velvet Underground, so, as Haynes dramatizes the music—that slow, deliberate, building screen of separated guitar notes, each one sounding a gong on the scale of the drone of the song—it becomes part memory, part the lift of finally hearing the song you came to the show to hear, and part event. It is foreboding and concluding all at once, pure fatalism: this story is set in stone, and nothing can alter it. Then the Factory actress Mary Woronov narrates, as a talking head: “Barbara Rubin brings them in, they’re all dressed in black. And they started playing. They played ‘Heroin’”—her voice giddy with the absurdity of such a musical handshake, or the daring—“We were like…” and her expression fills in the missing word, “WHAT?” With the song still finding its footing—Haynes uses four minutes of the song’s seven, but it feels complete as he weaves it in and out of what’s on the screen, bringing the sound down when people are talking, up when only pictures flash by—he shows footage of Woronov in the Factory. We see Malanga with his whips, with Cale in a voice-over as Warhol lays a framed painting on the floor: “The thing that was so encouraging and inspiring about the Factory was, it was all about work.” Lou Reed in a voice-over, over his own music, describes Warhol as a leader, pushing him to go further: “Every day he’d say to me, ‘How many songs did you write?’ ‘I wrote ten.’ ‘Oooohhh, you’re so lazy. Why didn’t you write fifteen?’” There’s a montage of Factory people, with Cale in voice-over, while the song is still opening, before any singing has begun: “People would come in, faces would come in, that you recognize, faces would go…and it was all commerce.” There is a menacing black-and-white photo of Warhol in dark glasses. In “Heroin,” Reed begins to sing, and a split screen opens off the Warhol image, filled with sped-up color footage of Warhol talking like a machine wound up too tight. Then again, in color, two montages: on the left, again sped-up film of the Factory, Warhol works mounted on the walls; on the right, other work on the floor. As the tempo of the music picks up, both screens quicken even more in a montage of constant busyness, hurry, time running out, what’s cool in art and hair and clothes changing so rapidly that if you don’t get it done today it’ll be out of style tomorrow. Faster on the screen, faster as the band plays. There are iconic Warhol images: Jackie, Elvis, flowers. On the left, a huge chandelier; on the right, Tucker and Reed on a couch as Cale plays. “Andy, he’s a divinity,” says the Factory person Danny Fields in a voice-over. “He [Warhol] was like a father always saying, ‘Yes, yes, yes,’” says Jonas Mekas in another. As frenzy begins to take over the music, there are split screens of Warhol focusing his film camera, Factory people dancing, lounging, being seen, posing, auditioning for Warhol movies by lounging, Malanga and the filmmaker Jack Smith dancing, Bob Dylan in his screen test, looking down, dour, outside the scene. With the music feeling louder, even if it isn’t, the Factory star Edie Sedgwick dominates one screen while an image of Warhol behind his camera holds at the top. Warhol saying, “You don’t have to do anything, just what you’re doing,” but very much directing, putting both confidence and doubt into the people looking at the camera. Sheafs of art materials. With the music still rising, there’s a pan to a huge Jackie on top of stacks of work. With Warhol behind the camera, Woronov appears in her screen test, with a voice-over: “There was no direction. Warhol never made a sound. But his presence was a sound.”

The music goes down, leading into the final conflagration, a complete contradiction and erasure of the still-life screen tests of people playing dead. “And I’m better off than dead,” Reed sings under a rushing montage of Warhol as a satanic cult leader, Sedgwick applying makeup, Warhol in a triple, autocratic image, men in dressing rooms, faces against a wall as Cale’s viola begins to screech, more Warhol, footage of the band playing, Warhol and Reed in dark glasses, the song heading into a last “And I guess that I just don’t know,” Warhol against a black background, head held back, mouth open, leather jacket, mirrored glasses, Reed in a close-up that zooms in and out, face to eyes to face, then a single eye, then Warhol talking over the music of his own Gesamtkunstwerk: “We have this chance to combine music and art and films altogether—we’re still working on—the biggest discotheque in the world.” And then Nico in her screen test as the song nears its last notes, notes that play finality. At first, there’s just the top of a blond head, then her full face, looking as if to affirm impassivity as a ruling value. She leans back, crosses her legs, tilts her head to the side, as if nothing could impress her, not even the song, which is over, but which has, in this long sequence, left its fossilized footprint in ancient mud to be discovered millions of years in the future.

All the different representations of “Heroin” up to this point make the song feel different from any other, a thing in itself, with the person who putatively wrote and sang it merely part of its story, not its author. You can hear the revolution take place, in the length of a song. You enter into history, Václav Havel’s proclaiming the band the inspiration for Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, as today people are still living it out as a sign of another life, a sign of freedom. Caught between Cale’s refrigerator and Bo Diddley, it’s a fable, a dream realized in a sound overwhelmingly grand, the words standing out like bodies, that clipper ship, the chance to feel like Jesus’ son. It makes addiction—putting a substance in your body so it can replace your soul—sound heroic, and it brings to mind that old line about how the first Velvet Underground album only sold a few thousand copies but everyone who bought it was inspired to start their own band. How many heroin addicts did that first album inspire? The band members might have cared, when junkies with bones all but sticking out of their faces came up to tell them how “that song changed my life.” The song didn’t care.

*

With Cale gone, with the drone out of the sound, the film does become Behind the Music. “They were unique in the beginning,” says the onetime Warhol assistant Joseph Freeman as a talking head. “Every member was an equal contributor in their own right. Now they were like a regular rock ’n’ roll band. And they had a brilliant creative person totally in charge.” They went on—leaving, on their last album, the beloved songs “Rock ’n’ Roll” and “Sweet Jane”—but up against “Heroin” these were novelty records.

Haynes shows the band members old. There are death notices. And then there is Lou Reed, on a stage, playing “Heroin” on acoustic guitar, all sensitivity and wistfulness, as if it’s a confessional ballad by James Taylor. The performance feels hollow, old hat. There’s nothing to see here, nothing to hear, nothing left. Go read Jesus’ Son instead. But then, inexplicably, it grows in strength, and you see that Reed is there with Cale, his viola playing quietly, and Nico, her hair brown, looming behind them. The song grows a body; it grows into its own body. The scene is from 1972, at the Bataclan in Paris. You realize—Todd Haynes, finding this footage, realized—that the song can take any form, and will. By the end, you might think you are privileged to have seen the best performance the song ever received. Todd Haynes has made a film about a song, and the song has made the film.