In June 1971, Rosemary Mayer began attending a women’s consciousness-raising group in New York City. She went with her friend, the artist Adrian Piper, and sometimes with her sister, the poet Bernadette Mayer. In her journal she wrote that at one meeting, Bernadette “kept talking abt. how being an idealist should not be a comment but a step to other goals. She had no idea what should come next but just that things might be different & there should be something to do to change it all.” What might come next was the big question.

Mayer was born in the Queens neighborhood of Ridgewood in 1943. Her father did upholstery work and her mother sewed; one uncle was a ribbon salesman and another worked for a fabric manufacturer. She and Bernadette were raised in a Catholic household, and Rosemary later said that her artistic work was influenced by “all the variety of textures…marble, gilding, polished wood, painted ceiling, the statues” in the church the family attended. In college she studied classics, becoming fluent in Latin and Greek, but turned down Harvard’s offer of a graduate fellowship in order to pursue art. In 1967, at the School of Visual Arts, she met Piper, who immediately noticed Mayer’s uncanny command of intellectual subjects, physical materials, and color.

Mayer’s journal from 1971—excerpts of which were edited by her niece, Marie Warsh, published in a limited edition in 2016, and reissued in 2020—documents the period when she was twenty-eight and living in a loft in Tribeca. (Bernadette produced Memory, a monthlong photographic and textual record of daily life, the same year.) It shows her amid a slew of worries, including about money—“I should cut my pair of pantyhose to shreds—& mail them to who’s responsible for people having to work”—and about time, both its scarcity and glut. She wishes she woke earlier, did more during the day, was thinner, had more fulfilling love affairs, and came up with more ideas for art: “Man…do I need ideas. Worse than I need a lover.” She is frustrated by the deficiencies she perceives in her work and disconcerted by her desire for artistic fame. During its run from 1967 to 1969, she had contributed text-based conceptual pieces to the downtown magazine 0 to 9, which was edited by Bernadette and the performance artist Vito Acconci, to whom Rosemary was briefly married: a page of tally marks measuring the time it takes to smoke a Chesterfield King Size cigarette; a proposal to redirect the mail sent to one side of a New York City block to the opposite side and vice-versa. She had also begun to experiment with deconstructed paintings made on canvases that had been removed from their stretchers.

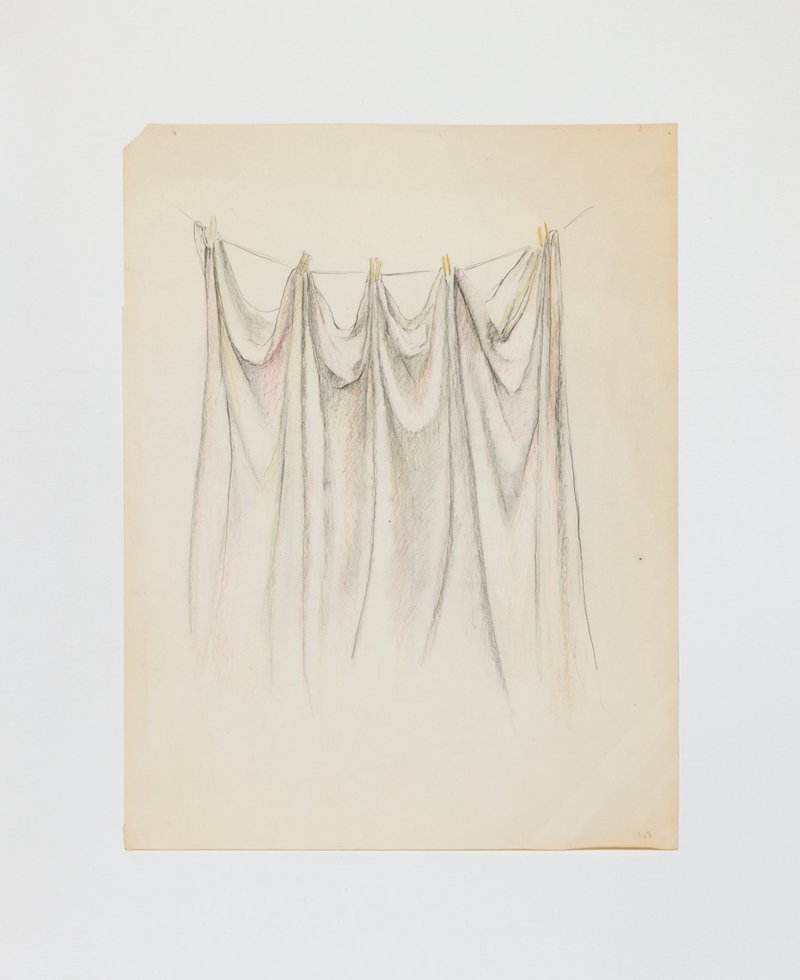

In her journal Mayer thought through specific problems related to her art, such as the vexed relationship between paint and fabric, concerns that a work’s beauty distracted from its seriousness, and how best to incorporate knots into her new fabric sculptures. She also addressed these issues in her sketchbook, exploring what she called “impossible” pieces. These drawings afforded, she writes, “a chance to play w. colors & all the possibilities of draping, tying, sewing, etc…w.o.$ & they can be unfettered by space & size.” This was a pivotal year for Mayer, in which she was developing her future artistic community and discovering a set of materials and a vocabulary that were expressly her own. Hints at what is to come are little thrills for the reader, as when she writes, “Art pushes the boundaries where afghans & scarves & pillowcases don’t. Could they?”

In 1972, Mayer and nineteen other women—among them Nancy Spero, Agnes Denes, Howardena Pindell, Louise Kramer, and Barbara Zucker—founded A.I.R. Gallery on Wooster Street in SoHo. It was the first cooperative gallery in the United States run entirely by women, a collective space of their own. Mayer’s contribution to the inaugural exhibition suggests that she had found a way forward amid her journal’s thicket of questions. Named for the fourth-century philosopher and astronomer, Hypatia (1971–1972) was a wall-hung sculpture consisting of a pair of nearly ten-foot-long cascading panels of cheesecloth and champagne-colored satin—each intermittently ruched with rope and gradually overlapping like the separate halves of a diptych slowly merging. The next spring, A.I.R. hosted Mayer’s first solo show, which featured three more large fabric sculptures—Galla Placidia (1973), Hroswitha (1973), and The Catherines (1972–1973)—each, like Hypatia, named for historical figures: the fifth-century Roman empress, the tenth-century German poet and playwright, and a legion of Catherines, including the fourteenth-century mystic and papal adviser Catherine of Siena and the fifteenth-century Cypriot ruler Catherine Cornaro. These were women, Mayer wrote in 1977, “who wouldn’t comply,” and she pictured them “enveloped in huge gowns, over centuries.”

Advertisement

Galla Placidia is the most ambitious of these draped fabric sculptures, and one of three displayed in “Ways of Attaching,” the Swiss Institute’s impressive new survey of Mayer’s drawings, sculptures, and “temporary monuments” (a series of outdoor installations that she worked on between 1977 and 1982). Peach, spring green, lavender, purple, and ochre layers of satin, rayon, nylon, cheesecloth, and netting are draped over a minimal structure of curving wooden rods, and the whole piece—a commanding nine feet high, five feet wide, and ten feet long—is suspended from the ceiling, though it equally appears to rise up from the floor. In works like Galla Placidia, Mayer was interested in creating complexity through simple means and subtly revealing the vulnerability of the work to gravity and air currents.

When I first saw Galla Placidia I thought of a rowboat whose underside is continuously cleaved by a vertical curtain of water. Mayer’s manipulation of the different fabrics creates the illusion of both solidity and flow. Light fills the blousy curves of the netted sides, while the opaque “curtain” plunges heavily to the floor. Yet for all its paradoxical voluminousness, the sculpture is ethereal, a floating object that seems to have only partially materialized in the room. In an unpublished essay from 1973, Mayer wrote:

Like liquids and natural phenomenon, fabric too is subject to gravity and natural forces. Its forms are accidental and inevitable. Like waves in water or leaves on trees, in reality fabric forms are never the same. Only when reproduced in a two dimensional medium can fabric forms be seen still and definite.

The textures of her materials not only reference the clothing of the women she honored but describe their contingent existence. “All their colors, the textures of their garments,” she wrote, “the hazy voluminous shapes they leave now hovering…. Presence caught in thin veils, films of color on color.” That women could be at once present and absent socially, politically, and artistically—the “51-percent minority,” as Shirley Chisholm articulated in 1970—was a central complaint of the feminist movement’s second wave. Mayer’s work is not only feminist but humanist, concerned with impermanence and seasonal cycles, redefining monuments and memorials, and linking the great spans of time and space to individual experience.

*

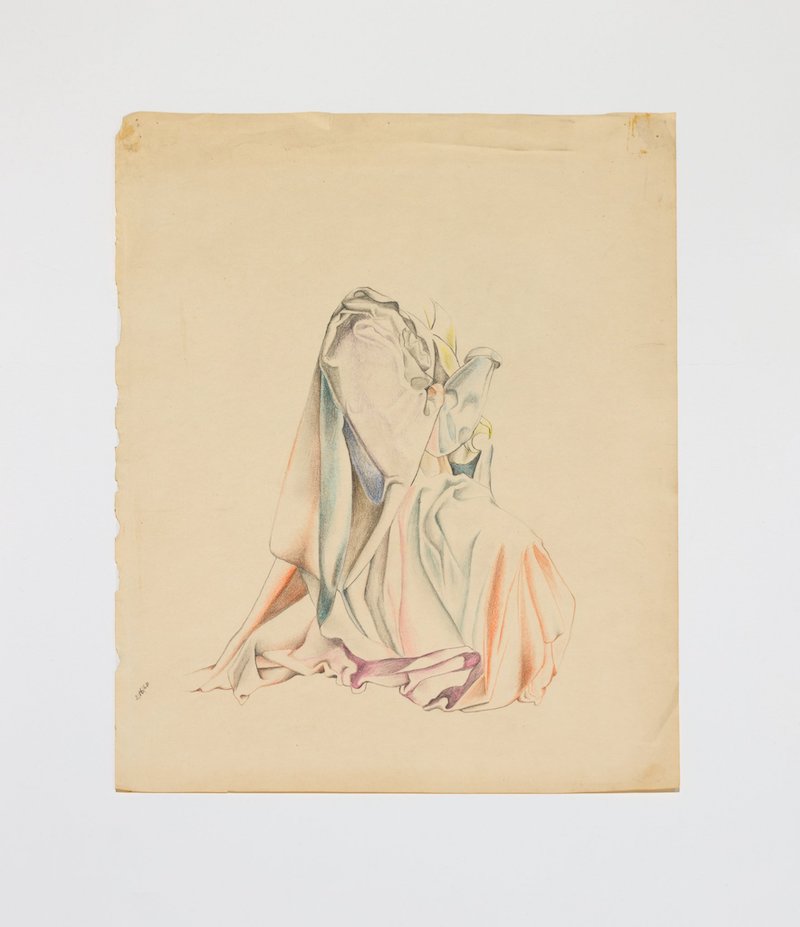

Mayer made her last draped fabric sculpture in 1973 but renewed her interest in the “impossible” pieces she had sketched only a few years before: the knotted networks of cloth became detailed, abstract renderings of fabric, by turns billowing and tightly compressed, drawn in colored pencil and ink. In this medium she continued to explore the lives of women, using diaphanous layers of blue, orange-red, yellow, and purple in Lucretia in Ferrara 1509 (1973) to depict Lucrezia Borgia, an arts patron and member of the notorious Italian Renaissance political dynasty. There are no known portraits of Borgia, and Mayer imagines her instead through her disembodied garment. Her resurrection of such women “lost” to history is only ever partial; her subjects remain in a contingent, transitory state.

On a trip to Europe in 1975, Mayer saw work by the Mannerists Parmigianino, Matthias Grünewald, and Jacopo Pontormo—reproductions of which she recalled seeing as a child. She felt a particular kinship with Pontormo, and later told the art historian Gillian Sneed, “I was living in Post-Minimalism, a time after a time of clarity, and Pontormo was in a time after the clarity of the Renaissance.” Pontormo’s rendering of drapery directly informed the play of form and formlessness, volume and light in Mayer’s drawings and sculptures. “His figures and drapery have the same unease, equally tentative, without mass,” she wrote in 1977, as in his painting Deposition from the Cross (1525–1528), whose figures seem to float upward rather than descend toward the ground as the title implies. They possess a buoyancy that is evident, for instance, whenever Pontormo paints a figure whose knees are slightly bent: the ballooning orange- and pink-robed figures in Visitation, and Mary in Annunciation that accompanies Deposition in the Capponi Chapel in Florence. Back in her studio, Mayer produced a series of small “formless” wire sculptures using aluminum screening torqued and twisted into coils. The colors of her palette here gain an additive aspect: in Crescentia (1975), on view in “Ways of Attaching,” a peachy-orange section of mesh visible through a lavender one becomes a pink suggestion.

In 1976 Mayer began translating Pontormo’s diary, and in 1982 she published a book that included her translations of his entries from the last two years of his life (1554–1556), accompanied by color plates of her own work. “I wanted his language and mine to disappear into his days,” she writes in a brief essay for the book, which is displayed in the Swiss Institute’s reading room. Pontormo’s diary is surprisingly tedious, an austere accounting of meals and only occasional artmaking: “On the 15th of March I started the arm that holds the belt, that was on Friday, and at night I had an omelet, cheese, figs and nuts and 11 oz of bread.” Even when he mentions the cycles of the moon and the seasons—subjects that were of significance to Mayer—they are made in relation to his digestive health. “All waxing moons are harmful if you’re full of mucus,” he counsels.

Advertisement

Why was Mayer so enamored of Pontormo’s diary? Perhaps she found the steady progression of dailiness reassuring—that art and life could so neatly coexist. In a letter to her sister from December 1976 (published in Letters of Rosemary and Bernadette Mayer 1976–80, a new collection of correspondence edited by Sneed and Warsh), she writes,

I really want to have a life, not just art. I’ve done just about all I decided I wanted, needed, to do, several years ago. I have the studio, involving concerns, enough of a reputation. But I feel there isn’t much else. It’s the same sort of thing I’ve been thinking about for at least a year. Jobs, my own work, whatever, get me so busy there is little else.

Like Pontormo, Mayer was an orphan. Her parents died within two years of one another, when Rosemary and Bernadette were in their early teens. In an unpublished artist’s statement from 1983, Mayer wrote:

Between the time I was ten and when I reached twenty almost everyone in my family died. I know I was much affected and still am by the loss and sorrow which permeated my childhood. Escape from the horrors of the everyday was a continuous goal of my adolescence…. I am also left with an overriding sense of the transience of every thing, person and circumstance.

She recognized the effects of this loss in her sister, too. In a letter to Bernadette in October 1977, Rosemary asks, “What is the fascination you have, and I have too, with past thoughts, events – we never each in our own way let go of it – I try to understand my reorderings – reusing. How do you think about yours?”

This question is most interesting in relation to Mayer’s subsequent works, a series of transitory outdoor installations documented in the 2018 book Temporary Monuments: Work by Rosemary Mayer, 1977–1982. The first of these, Spell, was installed on April 8, 1977, in the farmers market in Jamaica, Queens. Mayer tied fabric and ribbons to three white weather balloons, on which she painted the phrases “Iris Return,” “Crocus Return,” and “Hyacinth Return” as a way to conjure springtime and encourage vegetal growth. “Iris is written in red,” she explains in an essay about the work. “Orange-reds and greens hang from the balloon. Others are spread on the blacktop. The wind moves them less as the rough ground catches more of their surface, tangles the colors in pebbles and fences.” In a photograph of the installation, two lines of orange-red fabric angling skyward with a large white balloon hovering at their apex, while trails of the fabric snake across the asphalt.

Given Mayer’s written description, it’s possible to omit, in the mind’s eye, the rest of the scene—the people, detritus, and buildings in the background of the photograph. The colored lines of the fabric swags climb toward the blue sky, the balloon mixing with the clouds, unfettered. Pontormo’s diary may have been a model for grounding oneself while lifting off from the earth, a way of feeling free without letting go completely. Mayer writes:

He made himself a static, withdrawn life; made convoluted, floating work. He used his diary to know which days were passed, what foods had kept him well enough to work. A thing to hold onto the way kids hold balloons, but not like the balloons, like the tension in the hand that holds the cord, wraps it around a few fingers or the spread of joints where the hand and fingers meet.

She imagines being not the balloon, but the tension in the hand, connecting the drifting object and the earth.

At Christmas 1977, Mayer subscribed to Scientific American, Archaeology, and Sky and Telescope. For her next temporary monument, Some Days in April, installed during the week of April 17, 1978, in Hartwick, New York, she tethered seven balloons to beribboned stakes in an open field, without an audience. She wrote names and dates on the balloons to memorialize friends and family members who shared birthdays in April. She also wrote the names of flowers then in season and the stars that were visible in the sky. Beyond seasonal coincidence, she saw the flowers and the universe as linked in a cosmic flow of matter: the former, crushed and decaying, “stopped to slowly turn to oil and lavender gases.”

Mayer’s method of reordering, as she puts it in her letter, is cyclical in these monuments, immersed in the seasons and the phases of the moon. In February 1979, she made Snow People in the yard of the public library in Lenox, Massachusetts, where her sister was then living. Fifteen snow men and women populated the garden, each bearing a sign with a name in plural—Ediths, Annas, Fannys, Williams, Adelines, Thomases, and so on—all names of nineteenth-century inhabitants of the town. Each body stands in for many bodies; each memorial is many memorials, collapsing time and history until the snow melts.

Two months earlier, Bernadette had composed her sublime book-length poem Midwinter Day, a record of a single day—December 22, 1978. In that poem she writes about small moments folded within a larger view of her own life, at once nestled in intimacies and exploding with revelations about love, memory, dreams, and seasons. In a letter from May 1979, she tells Rosemary,

I read nothing lately but what has been written by women. It all came out of writing MIDWINTER DAY where in the last part of the poem, where I had planned to talk about aesthetics, I wound up talking about art and family, writing and being a woman and my wonder at how little information about the past has been transmitted and made available to me through women, so I could know, say, what a mother felt like in the Middle Ages or even literate ancient Greece.

Bernadette hits upon the same desire for interconnectedness that stimulates her sister’s evanescent monuments—threading personal memorials within the long span of history, thereby giving form and shape, however tenuous, to the residual traces of a life, whether their own lives or those of women in the past.

*

“Where is all the knowledge – astrology, myths, magic, feelings, that my work now doesn’t allow?” Mayer asked herself in her 1971 journal. There is no clearer answer than in Moon Tent, a temporary monument made over two days in October 1982. A friend of hers, the art historian Robert Hobbs, owned a house in Lansing, New York—a one-room cube built into the side of a hillock facing Cayuga Lake and topped with the wooden frame of a pavilion, like the skeleton of a Greek temple. Mayer wrapped the frame in translucent glassine paper (“the paper resembled a baroque confection—architecture as whipped cream or cumulus clouds,” Hobbs recalled) and invited friends to sit under it from dusk till dawn. The installation, lasting only one night, provided a communal experience in a liminal space, an open temple for tracking the seasons and the weather, the flora in the surrounding landscape, and the constellations in the sky above—always present, but in another sense only present when time is taken to observe them. It is a chimerical work, encompassing many of Mayer’s lifelong concerns—an elevation of humble materials, an assemblage of textures, a linking of the everyday and the universal—and so ephemeral it seems hardly to have existed at all. Writing about it, Mayer summons a host of primal feelings:

Imagine living, as people once did, with the bodies of all in your family who died before you buried below your floor or just outside whatever shelter you lived in. Imagine presents of food or drink or flowers or some substance considered sacred to the believed-to-be-present spirits of these people who had together produced you. The dead could live when it was thought they did. Like ghosts, floating in somewhat human form, seen from the corner of an eye, resembling figures known in dreams. They could glitter, change colors, fade past transparency to disappear.

Mayer died in 2014. She continued to make work through the last decades of her life, but was largely left behind by the art world, a casualty of proliferating commercial galleries and a fervid market that had little use for her ephemeral works. In her letters to Bernadette in the 1970s, she writes of the exhausting negotiation between managing her art career and editing math textbooks for money. In 1982, she complains to a friend about the difficulty of finding freelance work and of her new full-time job at an advertising agency. It was all time spent away from making art, and her omission from the art world feels brutal, if also terribly mundane.

Yet in the spirit of seasonal changes, she’s back, if only for a time. The renewed interest in Mayer’s collective memorials, modest celebrations of the changing seasons, and documentation of fugitive details feels apt in this era of isolation and quarantine. In addition to “Ways of Attaching,” Mayer’s work is currently on view in “Greater New York,” at P.S.1. The exhibition includes four of her “Noise Drawings” from 2001, each an accounting of a single day’s sonic haul. She translated each sound—an onomatopoetic feast of words such as “hiss horn hum” and “lightning thunder rain wind chime”—into riotous grids of color. They are aural diaries and synesthetic inventories alert to all the elements of life.