São Bernardo do Campo—In early December, Luiz Inácio da Silva—the former president of Brazil universally known as Lula—took the stage at the ABC Metalworkers’ Union, in greater São Paulo, before a screening of the film Marighella. All of the symbolic elements lined up. This was the place, in Brazil’s industrial heartland, where Lula began his career as a labor leader back in the 1970s; and it was the building from which he had been hauled off to prison by federal police in 2018.

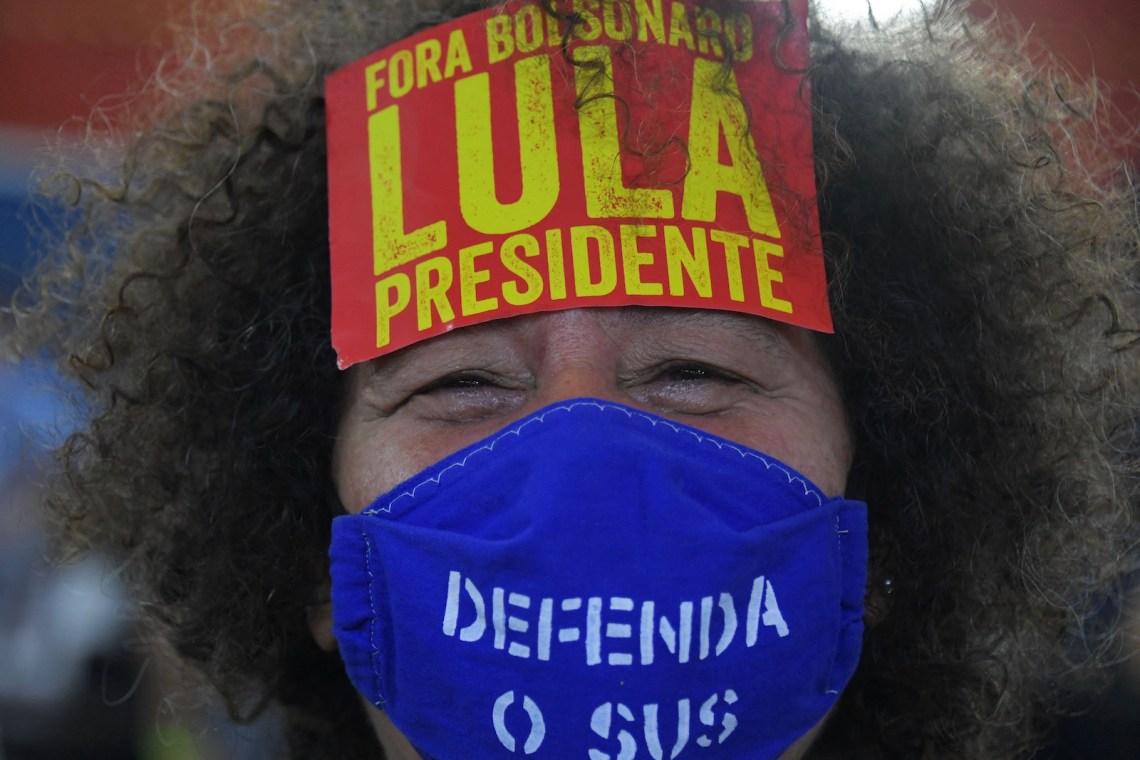

The movie, about Carlos Marighella, a Communist dissident who was murdered in 1969 by the US-backed military dictatorship, had had its release delayed for two years because of censorship by the extreme-right government of President Jair Bolsonaro, according to its director, Wagner Moura (the star of the Netflix drama Narcos). Today, Bolsonaro is weakened, while Lula, his corruption conviction thrown out, is once more free to contest the presidency, an office he last held more than a decade ago. At the screening, he greeted throngs of his blue-collar supporters, taking selfies and giving hugs, as the cast and crew assembled to celebrate lives of determined resistance, the kinds of stories that constitute the ideological foundation of Lula’s own Workers’ Party.

In an address, a pastor named Henrique Vieira made an even more forceful comparison. He started by saying that even though Brazil’s evangelical Christians were often dismissed as conservative, they are working-class people, and they are suffering. Many may have voted for Bolsonaro, but their true place, he said, is within a renewed left. Then he began to speak about Jesus Christ. He is a skilled preacher, and I could see that his words electrified the audience. “Remember, the Gospel did not end with the crucifixion,” he boomed. “The Gospel ends with the resurrection!” Bella Camero, an actress who plays a young guerrilla in the film, began to weep behind her coronavirus mask and dabbed the tears from her eyes.

Lula is back at the center of Brazilian politics. These days, he often dominates headlines, even more than Bolsonaro. Ever since the Supreme Court annulled the conviction, last year, that had put Lula behind bars—and ruled that the judge who convicted him, Sergio Moro, had conducted the case in a biased manner—the veteran campaigner, now seventy-six, has been indefatigable. Railing against the embattled far-right president, Lula is offering many Brazilians the hope of a return to normalcy, if not also to the good years that many remember from his two terms in office, from 2003 to 2010. Every poll on voting intentions currently suggests that he would beat Bolsonaro in a landslide (and trounce every other likely contender, too). Another, less conventional measure of Lula’s popularity is that, according to Spotify, his interview with Mano Brown of the legendary São Paulo rap group Racionais MC’s was Brazil’s most-streamed podcast episode of 2021.

If all that counted were popularity, Lula would likely have won back the presidency in 2018. He had left office eight years earlier with an approval rating of over 80 percent, and he was well ahead of Bolsonaro in the polls when he was taken to prison at the height of the hard-charging and unscrupulous “Lava Jato” (Operation “Car Wash”) anticorruption crusade. But back then, in 2018, the courts upheld his imprisonment. At the same time, the head of the army—in two notorious tweets—implied that the Brazilian military would not accept any other decision.

Powerful institutional forces worked to keep the Workers’ Party out of the presidency in recent years: a politicized judiciary, a military that has once again under Bolsonaro become entrenched in government, and a parliamentary body willing and able to end a democratic presidency on a technicality. In 2016, Congress chose to remove Lula’s chosen successor, Dilma Rousseff, from office, in a move that many Brazilians considered a parliamentary coup. While Rousseff was unpopular at the time, no one ever voted for her vice president, Michel Temer, to take power and install a completely different, much more conservative government.

In weighing whether Lula might return to govern in 2022, it is crucial to understand how and why Brazil’s varied institutional forces—where power actually resides in moments of crisis—might be willing to let him.

*

Brazil is so worn out by the pandemic, and by the incompetent and embarrassing Bolsonaro, that conservative elites may decide Lula is, after all, someone they can deal with, someone who at least knows how to run this country. Bolsonaro, fervently antidemocratic throughout his entire public life, has always made it clear he would lead a coup d’état if he could pull it off. But Lula has a great deal of support, and given the alternatives—either a more entrenched and reckless far-right government or an uncertain future with some other unpopular figure—it may be easier for the powers that be to simply let democracy run its course.

Advertisement

This could end the instability that has plagued the country since the middle of the last decade, and it would, with luck, deliver a president with full democratic legitimacy for the first time since then. But it would only take one institutional actor to disrupt this balance once more. Besides the judiciary, the armed forces, and Congress, the most powerful force in the land may be the local “business community”—or, to use language favored by Marxist intellectuals when the Workers’ Party was founded back in 1980, the “national bourgeoisie.”

“Brazil being Brazil, you can’t do anything without the business community on your side,” economist Monica de Bolle, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, told me. “At the same time, you can’t do anything without legitimacy. You need the electorate on your side, too.”

It is now widely accepted that Bolsonaro had the backing of much of this economic elite when he won the election in 2018, but he has lost a significant part of that community’s support during the pandemic. He tried to put growth ahead of public health—dismissing both the threat of Covid-19 and the efficacy of vaccination in a Trumpian fashion that appealed to few Brazilians—but failed on both counts. Brazil went through four health ministers, as even avowedly right-wing doctors said they could not work with the unreasonable president, and more than 600,000 people have lost their lives. The state of the economy is also a huge problem, especially for working people: the price of basic goods has shot up and widespread hunger, not seen at these levels since before Lula took over, is decimating the country.

The business class can recall that it did very well under Lula’s pragmatic, results-oriented administration. Buoyed by a commodities boom in the 2000s, the Brazilian economy made the rich a lot richer, while social programs helped pull tens of millions of normal people out of poverty.

It is not hard to guess at the desires of the economic elite, as its views are well represented in the national press, but in October a leaked conversation between the powerful banker André Esteves and his investors gave a sense of how this thinking works behind the scenes. He said that Bolsonaro would remain the favorite for 2022 if he could only “keep his mouth shut,” but that if Lula indicated he would adopt pro-business policies, he could be the best option. The problem, de Bolle told me, is that twenty years ago there was a convergence between what the business community wanted and what regular people demanded. The priorities of these two constituencies have diverged widely during the pandemic, she said, with the elites in this wildly unequal country insisting on nebulous free-market “reforms,” while ordinary Brazilians clamor for the basic security of jobs, housing, and food. “The question I keep asking myself,” she said, “is how do you bridge that gap?”

Bolsonaro himself has little interest in economic policy (his project is purely political: the annihilation of the left), handing that off to a Chicago-trained economist named Paulo Guedes, whom he named as his finance minister in a signal that the markets would get what they want. But the administration has managed little more for that constituency than a pension reform, before the virus arrived. Another thing that worries the business class is that Bolsonaro has recently aligned himself with the so-called centrão, or big center, a cluster of ideologically flexible parties in Congress. In its pejorative sense, centrão denotes the group in Brasília that will make a deal with anyone in exchange for pork. It is not so much Bolsonaro’s ideological extremism that has alienated the elite—the business class and the media backed the military takeover in the Sixties—but his failure to deliver economic stability.

The loss of national prestige under Bolsonaro has added insult to that injury. In October, a clip of the president at the G20 summit in Rome went viral in Brazil. He wandered aimlessly around the room, ignored by other world leaders, until he eventually settled on chatting with a couple of waiters, whom he tried to interest in his Italian heritage.

For his part, Lula pulled off something of a diplomatic coup a few weeks later, when he was received in grand fashion by President Emmanuel Macron in Paris, and then by Olaf Scholz, soon to be Germany’s new chancellor, in Berlin. For many Brazilians, this split-screen was a clear sign that while the big gringo countries rejected Bolsonaro, they accepted Lula; and it was a reminder of the days when the former union leader used to travel the world, spreading the good news of a bright Brazilian future. On social media, Brazilians joked that since the bosses wouldn’t get on and hire a new one, Lula was being forced to “freelance as the president.”

Advertisement

Economic insecurity is a theme that Lula, in his constant public and media appearances, lands on all the time. He almost always traces his own path from abject poverty to the presidential palace, saying that, even as a poor child, at least he could look forward to the possibility of a stable job. The one he landed, at a unionized factory, gave him prospects no young Brazilian can expect today. With workers’ rights destroyed by Temer and Bolsonaro, he argues, Brazilians are forced to hustle, doing gig work for apps, never sure how long they can make a living. At a meeting last month of small-scale food producers in São Paulo, Lula sat and listened to farmers and fishermen for hours. Then he took the podium, denounced the impoverishment of the country, and railed against tech companies that mistreat workers as their owners in the United States get rich.

Lula likes to relate how, during his 580 days in prison, he read about the history of slavery in South America, and he ties that story of oppression—and his own biography—together with conditions in present-day Brazil. “This has always been a very undemocratic country,” he said in his speech at the union hall. “Every time someone appears who defends the poorest and the needy, that person is punished. They are put in jail, or killed, or hunted down.” On a recent trip to Spain, he got specific about who was to blame for his own imprisonment: it was, he said, “a joint effort carried out by the United States Justice Department, the Brazilian judicial apparatus, and the media.” Principal figures in the Lava Jato investigation collaborated with US officials before and during the operation.

At the same time, Lula is seen as a man who doesn’t bear grudges if they get in the way of results. In recent weeks, he has made noises that he might team up with former São Paulo governor Geraldo Alckmin, a longtime member of the center-right PSDB party, as his vice-presidential running mate. Whether or not that happens, it is a signal that he will be willing to work with people across the aisle. The PSDB supported the 2016 impeachment of his protégée Rousseff.

In Congress, Lula can count on more friends than Rousseff had. Bolsonaro, after failing to create a party of his own, is now in the process of joining the big-center Partido Liberal, but there is little appetite in that party for any embrace of fire-breathing Bolsonarismo. Indeed, its Senate leader, Carlos Portinho, told me in December that the party sees itself as a stabilizing force in Brazilian politics. “I think the 2022 election will be less ideological than the 2018 election,” he said, “and that would be a good thing.” Four years ago, many in Bolsonaro’s camp would have considered it an affront to the republic for Lula to run for president. Portinho is fine with his candidacy: “If the judiciary allows him to run, then he can run, and it will be the voters who pick the legitimate winner.” After all, he noted, the Partido Liberal had worked very productively with Lula in the past.

*

There is one grudge Lula has no reason to forget. In December, he blasted Bolsonaro as a “fascist” and, in the same breath, Bolsonaro’s former justice minister, Sergio Moro, as a “neofascist.” Moro entered national consciousness as the face of Lava Jato, and it was he who, as a judge, put Lula in jail in 2018. In 2019, The Intercept Brasil revealed that Moro had collaborated with prosecutor Deltan Dallagnol, obviously throwing impartiality to the wind. The high courts will be much more hesitant to intervene in presidential politics now, according to Eduardo Mello, an assistant professor of politics and international relations at the Fundação Getulio Vargas in São Paulo. “Anything could happen,” he said, “but the probability is low that the judiciary would make a decision that keeps Lula from running.”

Few defenders of the Workers’ Party, speaking frankly, will deny that corruption has been a part of Brazilian politics since the military dictatorship that ended in the 1980s, and they admit that Lula chose to work with a messy system in order to get things done. But in 2018, Moro threw the former president in jail on a very weak accusation, ruling that an apartment in a middle-class beach community—which Lula had never lived in, let alone owned—had constituted a kickback. It all seemed like a desperate attempt to remove the man from contesting the election. Pope Francis joined other voices in South America condemning “lawfare,” the use of courts to crush democratic movements, in the way that the Brazilian military used to do in the twentieth century.

Usually, top judges would block any low-level investigation that had committed any kind of procedural error, said Mello. But for a number of reasons, including enormous outside pressure, Lava Jato took place during an exceptional period—one that is probably over. “Corruption is a much less important theme for regular people than it was a few years ago,” he said, “with people instead focused on poverty, and the economy—so things have gone back to normal.”

Moro lost much of the Bolsonarista movement after a public rift with the president in 2020. He is now running for president himself, joining forces this time with Dallagnol, who is a candidate for Congress with the Podemos party, and Lava Jato has become the openly right-wing political project that its critics always accused it of being. Podemos will vie with the Bolsonaro movement for voters.

On the left, forces are more unified. Sâmia Bomfim, a congresswoman in the left-wing Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), wants her party to field a candidate this year, but if it comes down to a choice between Lula and Bolsonaro, her position is clear. “A super-wide united front will come together to fight against a genocidal president,” she told me. “I have no doubt that in a possible second round, we would actively join Lula’s campaign.”

Bomfim, who participated in mass protests in 2013 that ultimately rocked the Workers’ Party, calls the 2016 removal of Rousseff an “institutional coup.” She said that she thinks Lula’s moves toward the center are an error. “No matter what he does, the right will demonize him. I don’t think there is a good reason to trust in the enemy once more, in the same people that carried out the impeachment or even made possible his own imprisonment.” But she recognizes that articulating a sustainable left position in Brazil is a delicate, even risky matter. “I do believe that there could be another coup.”

This is no left-wing hallucination. In Brazil, especially in the Bolsonarista imagination, the military has always been the natural vehicle for a coup. Senior officers from the armed forces are even more present in the government today than they were during years of actual military dictatorship. Many of these figures, including Bolsonaro himself, trace their roots to a radical dissident faction within the dictatorship that believed the high command was too democratic. Bolsonaro has repeatedly threatened to carry out a golpe during his presidency. A rally in September seemed designed to demonstrate the masses that would back him—except that far fewer people showed up than expected.

Given Bolsonaro’s current levels of support, it appears unlikely that the military would back him in a desperate attempt to hold on to power, said Roberto Simon, a political analyst and author of O Brasil contra a democracia, a recent book on the Brazilian military as a geopolitical player in the twentieth century. In 2018, General Eduardo Villas Bôas issued a statement that the army was paying close attention to the “yearning of all good citizens to repudiate impunity and disrespect for the Constitution,” in what was widely understood as a message that the Supreme Court should dismiss Lula’s appeal and keep him in jail.

Whether or not they view Lula as an acceptable outcome in 2022 or as a real threat may depend on which Lula is put forward in the campaign. “Lula has many faces,” said Simon. If he appears moderate, with the backing of business elites, that is less likely to provoke the top brass. “I know that Lula has been trying to reach out to the generals and create direct lines of communication. I think this is the most likely scenario. Things will be different if he embraces more radical positions.”

Despite the institutional intrigue and political crises of the last few years, it is still true that the more mass support Lula has, the less power other political players will have to impose their will on the country. He spent 2021 building a remarkably wide coalition of constituencies, in a very large and divided country. But Lula himself knows that much of this game is about chance. In another of his recent podcast appearances, he complained that his opponents always say, “‘Oh, Lula got lucky, Lula got lucky.’” But he joked that in soccer, it’s natural to pray that your goalkeeper stays lucky—and politics is not so different. “We need a president that can be lucky!”