In the years following Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviet Union exhaled. It was a period known as the Thaw, and Natalya Gorbanevskaya, an aspiring young poet, was—along with many of her generation—shaped by the sliver of openness it brought after the long years of pervasive fear and murder. Nikita Khrushchev, the new leader, delivered his “secret speech” in 1956 denouncing Stalin’s cult of personality and repressive rule. New thinking, new shapes and colors, made their way in. Picasso’s paintings were exhibited in Moscow and Leningrad, and Natasha, as she was known to all, rushed to see them with her friends from university.

But for the intelligentsia, this dizzying moment also presented a new set of complications. Just a few months before cubism made its way to the Hermitage, Soviet tanks had brutally crushed the Hungarian revolution. Under Stalin, testing the limits of freedom meant possibly being sent to a Siberian Gulag or marched downstairs to a prison basement and shot. But how far could you go now? What would set off the regime? How critical could you be, and what exactly could you criticize? What art was permitted? And what kinds of difficult truths could be uttered above a whisper?

The testing ground for these questions was samizdat. The word was a contraction of “self” and “publishing,” usually by typewritten manuscript, and it was in every way a unique product of the Thaw. The state literally controlled all the means of publication, even down to registering every typewriter so a keystroke could be traced back to its owner. Samizdat was the intelligentsia’s solution. Composed on onionskin paper (sometimes up to ten or fifteen sheets typed at the same time) and passed from hand to hand, this became the dissidents’ way of building and maintaining opposition to a totalitarian state. They wrote about what they were witnessing, compiling lists of human and civil rights violations. They produced essays about what they should do and then other essays countering those points. Writing from the West was translated and circulated as well.

The network formed and strengthened around this writing. It was dangerous to produce—getting caught with samizdat could frequently get you sent somewhere far to the east—but this only increased the dissidents’ level of commitment. By the early 1960s, it was the underground method for reading the novels, short stories, poems, political essays, and memoirs that would never make it through the Soviet state censors. Samizdat writing quickly became the most interesting writing, passed from hand to hand illicitly, a sort of forbidden fruit. (A famous joke from the time recounts a mother saying that when her daughter refused to read War and Peace, she gave it to her to retype as samizdat, and she grabbed it and read every word.)

For Natasha, who had been writing verses since she was a young girl, the Thaw made her feel she could express herself more openly, but the options for having her work read were still few. When she was a linguistics student at Moscow University in the late 1950s, her first poems appeared on the university’s wall newspaper—pages of printed broadsheets pasted up around campus, to be read while standing. Other students attacked her as “decadent and a pessimist” for her dark, lovelorn sentiments. She also learned how dangerous poetry could be in the Soviet Union. After the quashing of the Hungarian revolution, some of Natasha’s friends were arrested for their poems, and she herself was detained at the notorious Lubyanka prison (the place where, not long before, inmates had been shot in the basement). Under KGB pressure, she revealed everything about the creation of the pamphlet that had contained the offending poems. In her mind then, at twenty-one, she still imagined herself a good Soviet citizen, a member of the Komsomol, the young pioneers. But afterward, she was filled with remorse and never forgave herself for betraying her friends.

On her release, she resumed her writing life—and samizdat now became central to it. At first, she would copy out her poems by hand and share them with friends. But after she purchased an old Olympia for forty-five rubles to write her thesis, she began typing them out. She used carbon paper that could create four copies at once. Natasha would reproduce the same collection as many as eight times, to “publish” an initial samizdat run of thirty-two. Her poems of alienation and loneliness would then spread as her readers made their own copies. “I enter my being like a plane going into a spin,” she wrote in one poem, part of her first samizdat publication from 1964, the year when she began putting together annual compendiums. In another, she is “not a flame, not a candle, but a light, I am a firefly in the damp, tangled grass.”

Advertisement

Increasingly, the samizdat drew Natasha into a community of dissidents. In the early 1960s, she helped organize two samizdat poetry magazines, Syntax and Phoenix, both of which so riled the authorities that they arrested their editors, charged them as criminals, and sent them to prison camps. Natasha continued to write. In 1962, she was even taken by a friend to meet Anna Akhmatova, a godmother to the country’s dissident poets. Akhmatova’s circle of young acolytes then included Joseph Brodsky, who would soon be denounced and put on trial for what were deemed “pornographic and anti-Soviet” poems. Then in her seventies, Akhmatova’s regal, uncompromising presence made a strong impression on Natasha, and she became set on her identity as a poet, with all the difficulties this life would entail.

If samizdat started this way for her, as a form of self-expression, Natasha was also beginning to see how it could unify the community of dissident artists and writers then increasingly under attack. It fused them together, providing a form of currency when all the usual avenues of culture were closed. But just how instrumental it could be in helping their burgeoning opposition to home in on a clear purpose, hammering away day after day at the same immovable force of the state—that only became evident once the aperture that had allowed some light into their creative lives began to close.

*

The Thaw ended for Natasha and her friends in September 1965, on the day Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel were arrested. Both were respected and established writers. Whenever purveyors of samizdat had been prosecuted before, it was almost always for invented or planted crimes, but Sinyavsky and Daniel were put on trial specifically for their words. They were charged under a new Article 70, which made “anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation” illegal and punishable by prison sentence.

On December 5, 1965, an official holiday celebrating the Soviet constitution, the dissidents gathered at Pushkin Square in central Moscow in protest, a terrifying prospect coming just a decade after Stalin’s death. The banners they unfurled gave an indication of their strategy: not to call for revolution or overthrow, but simply to ask the Soviet state to abide by its own laws—the civil and human rights principles codified in the country’s guiding charter. “Respect the Constitution, the Basic Law of the USSR,” they insisted, and “We Demand That the Sinyavsky-Daniel Trial Be Public.” A couple months later, Sinyavsky was sentenced to seven years and Daniel to five in the notorious labor camps in Mordovia.

The days of poetry deemed subversive simply because its themes were not cheery enough, those days were over. They were now fighting a war with the regime, and their only real weapon was onionskin paper.

Natasha made her part in this battle public in February 1968, when she signed a letter addressed to the troika of leaders then running the country and guiding the crackdown—Nikolai Podgorny, Alexei Kosygin, and Leonid Brezhnev—to demand that her friends Sinyavsky and Daniel, arrested for producing samizdat, be given an open trial, as mandated by law. “As long as arbitrary action of this kind continues uncondemned, no one can feel safe.” Natasha knew she was taking an enormous risk and that she was in a particularly vulnerable situation.

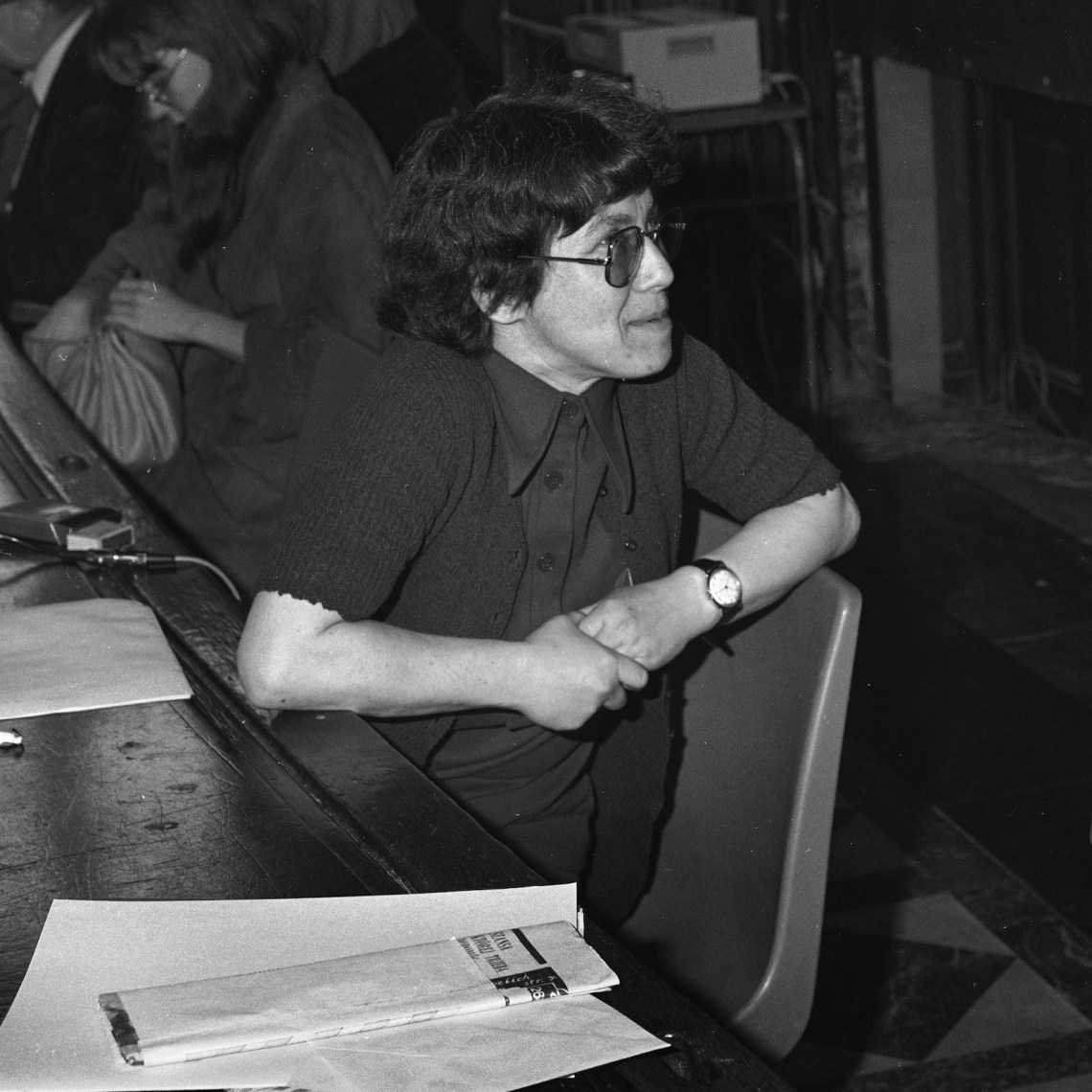

She was living with her mother and her son, Yasik, in one unit of a noisy, dimly lit communal apartment with shared bathrooms and kitchens. Natasha’s father had been killed at the front in 1943, and she had grown up with a single parent. Her own decision now to raise a child by herself—with the help of her mother, of course—was voluntary but unusual. There was a pervasive eccentricity about Natasha. In a photo from 1968, when she was thirty-two, she is dressed in baggy pants, a formless dark, knitted sweater, and tennis shoes. Her hair is messy and comes down only to her chin; cat-eye glasses dominate her face. And she was then pregnant again, once more without the child’s father’s involvement.

Two days after sending off her protest letter, she felt the hand of the state slap her down, and in the strangest, most unsettling way. Early in the last trimester of her pregnancy, she woke up ill one day and, fearing there was a problem with the baby, checked herself into a maternity hospital and was diagnosed with anemia. As in a horror story, once admitted, she wasn’t allowed to leave. In a series of notes that she managed to smuggle out, she described the ordeal in real time. “Why are they keeping me here?” she wrote. “After each ‘Wait until tomorrow’ I collapse like an empty sack.” After a few days, a psychiatrist examined her and deemed her insistence on being discharged a symptom of schizophrenia. She was then forcibly strip-searched and placed in an ambulance, where she was taken to Moscow’s main psychiatric institution, known as Kashchenko.

Advertisement

This was the KGB’s way of punishing her. Only the pregnancy had dictated she land here and not in a prison camp. She tried to be strong. “If they did want to frighten me, to throw me off the rails, to traumatize me, they did not succeed,” she wrote in her last note. “I am waiting for the birth of my child quite calmly, and neither my pregnancy nor his birth will prevent me from doing what I wish—which includes participating in every protest against any act of tyranny.” After nearly two weeks, she was suddenly and without explanation sent home.

It was in the days following her release, regrouping with friends, and still very pregnant, that she began imagining some further use of samizdat, extending its role of documentation, creating one central place to compile a detailed list of wrongs committed by the Soviet Union. Nastasha now had time on her hands; her due date fast approaching, she was on leave from her job as a translator at Moscow’s State Institute of Experimental Design and Technical Research. There were other intellectuals who had more standing among the dissidents, but they saw the job of compiling and retyping as menial. Natasha, though, was not afraid of work: she had the editorial skills and was a quick typist—and she was eager to do something. And so, that spring of 1968, Natasha slipped one of the pages of carbon paper into her Olympia—whose keys she had paid someone on the black market to alter to keep the authorities from connecting her political samizdat to her poetry samizdat—and started to type.

*

At the top of Issue No. 1, Natasha had given the journal a title, half-ironic and half in earnest: Human Rights Year in the Soviet Union. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (not exactly commemorated in the Soviet Union) had been signed twenty years earlier. For good measure she added Article 19 as an epigraph: “Everyone has the right of freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers.” The name that stuck was the one she used as a subtitle, Chronicle of Current Events, after a BBC Russian-language news roundup. It would become known simply as the Chronicle.

Natasha and her friends used the Chronicle to unload the burden of all the harm that had been done to them. All the events described at first concerned the small circle of intellectuals in Moscow and Leningrad, starting with an account of the trial of four among them who had been prosecuted for creating samizdat. Even Natasha’s recent ordeal made it in: “Without any warning and without her relations’ knowledge, Gorbanevskaya was transferred on 15 February from maternity clinic No. 27, where she was being kept with a threatened miscarriage, to ward 27 of the Kashchenko Hospital.”

She finished by the end of April and gave it an issue date of April 30, 1968. It was twenty tightly spaced pages, with seven carbon copies. Six of the copies were spread among friends to be retyped in turn, and one was given to a Western correspondent. The scribbled notes containing all the information that went into the issue were immediately burned.

Later, Lyudmila Alexeyeva, one of the dissidents who most helped with the typing of the Chronicle, described its style thus: “It would offer no commentary, no belles lettres, no verbal somersaults; just basic information.” The absence of embellishment felt to Natasha like a creative act. Not the experience she had writing poetry, which, she often said, seemed to her as natural and necessary as breathing, but a willed sort of chiseling away at emotion that was satisfying in a different way—that sharpened the focus.

By the second issue, Natasha began to innovate, adding more features to the journal. The most important was “News in Brief,” a kind of catchall for violations of every sort and updates on the various cases and prisoners. The first item in Issue No. 2, for example, read, “A lathe tore fingers from the hand of Vadim Gaenko in Camp No. 11 in Mordovia. Gaenko from Leningrad is serving four years under Articles 70 and 72 of the RSFSR Criminal Code for taking part in an illegal Marxist circle and issuing The Bell periodical.” She also included a long list of “extrajudicial political repression,” with the names of ninety-one individuals who had been expelled from their workplaces or kicked out of the party for various perceived offenses like signing protest letters or teaching outlawed books.

Most of the material came from friends who wrote what they knew on slips of paper or committed it to memory and then told it to Natasha, whose identity as the editor was an open secret. With this second issue, Natasha also moved outside the urban centers, with a letter from a group of Crimean Tatars who described the lingering psychic pain from the forced and brutal Stalin-era expulsion from their land. For the Chronicle to convincingly act as a legal brief for the aggrieved Soviet citizen, for it to focus dissent, it had to extend beyond the concerns of Moscow and Leningrad’s intelligentsia.

On August 21, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring. Natasha still felt guilty about the way she had turned on her friends in the wake of the Hungarian revolution. This was her chance to redeem herself. She had to show solidarity with the people of Czechoslovakia and the liberalizing moves of the country’s new leader, Alexander Dubček.

Natasha and a group of her friends, including Pavel Litvinov and Larisa Bogoraz, the wife of the imprisoned writer Yuli Daniel, decided they would stage a sit-down protest in Red Square. An act of such flagrantly public dissent had never been attempted on what was essentially sacred ground, mere feet from Lenin’s mummified body. They prepared by making Czech flags and banners with slogans like “For Your Freedom and Ours,” which Natasha then folded up and placed beneath the mattress in her three-month-old son’s pram.

Just before the appointed time at noon on August 25, she rolled sleeping baby Osya toward Red Square, an extra pair of cloth diapers and pants at his feet. The group met at Lobnoye Mesto, the stagelike raised circular stone platform in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral, where Ivan the Terrible was said to have carried out beheadings. And when the bell struck noon, the seven friends took out their banners and flags and sat in silence in the middle of the bustling square. Within minutes they were shut down.

A crowd organized by the KGB to rile up the mostly confused pedestrians began shouting at the protesters, “They’re all Jews!” and “Beat up the anti-Soviets!” Meanwhile, black Volgas, the cars of the KGB, sped through the square and police hopped out, roughly pulling the seated protesters off the ground and into the vehicles. Natasha, because she was still nursing an infant, was almost immediately released.

A few days later, she wrote a letter that appeared in The New York Times, among other publications. As the only participant “still at liberty,” Natasha described what happened in Red Square and expressed pride that, as she put it, “we were able even if briefly to break through the sludge of unbridled lies and cowardly silence and thereby demonstrate that not all citizens of our country are in agreement with the violence carried out in the name of the Soviet people.” But with her closest collaborators, Litvinov and Bogoraz, now jailed and soon sentenced to Siberian exile, Natasha felt increasingly alone. All the same, not knowing how long she had, she threw herself back into the work of samizdat.

*

By the end of 1968, the Chronicle was a fixture in the Soviet Union, a regularly appearing samizdat publication that told a continuing and highly detailed story of repression. Natasha didn’t see the Chronicle as an illegal enterprise. Its entire modus operandi was transparency—“glasnost” in Russian—uncovering the inner workings of the Soviet Union for the benefit of vigilant citizens. The concept of an underground newspaper had a major archetype in Lenin’s own prerevolutionary propaganda organ, Iskra, printed abroad and smuggled into tsarist Russia, where it had to be hidden and spoken about in hushed tones. The Chronicle was fueled by a different impulse, not building up a shadow revolutionary army, but rather exposing to light, one abuse at a time, the repressive quality of the Soviet state. Natasha and her fellow authors were interested in shattering the distinctly Soviet feeling of having two selves—one that whispered truths in private and another that was regularly called on to deny reality out loud. Lyudmila Alexeyeva, who by 1969 was retyping issues and also providing information from her contacts in Ukraine, described working on the Chronicle as pledging oneself “to be faithful to the truth.”

The Chronicle was demanding more and more of a sacrifice from Natasha, but this was also because it was becoming more important. She felt this acutely when the mother of a political prisoner just off the train from having visited her son rushed to meet her in secret so she could unload all she had learned. Natasha would take notes about who was having their food ration cut in that camp, who had been injured recently while carrying wood, who was sick and not receiving medical care. It all went into the next issue’s section on news “from the camps.”

With every added Chronicle reader, Natasha’s own chance of arrest increased. After ten issues, the KGB and its head, Yuri Andropov, had upgraded the threat level of the journal. And then there was the matter of the BBC and Voice of America, which would broadcast readings of entire issues. The stations saw the journal’s reporting as a reliable news source, a contrast to the Potemkin paradise presented in the pages of Pravda and Izvestia. Their frequencies were jammed from transmitting into Soviet territory, but they still managed to reach wily Soviet citizens with shortwave radios.

After her apartment was searched in late October 1969, Natasha knew she had to pass off her editorial duties to someone else, and quickly. But she had not been able to dispose of all potentially incriminating material when the KGB came knocking again in December, this time to arrest her. She had an envelope crammed with handwritten notes that was in the center drawer of her desk, and a few other crumpled pages stuffed in the pocket of her coat hanging by the door; the KGB would pounce on any handwriting to try to track down contributors. She watched the agents shake out books, hammer their fists against the floors and walls to find possible hollow hiding spaces, cut through cushions, and pour her kitchen utensils out of their drawers.

By the time the search was done, the agents had gathered a pile of paper a foot thick and dozens of books. Only then did they let Natasha know that she was under arrest. Three friends had stopped by during the search, and still concerned about leaving any incriminating papers and not sure if the KGB had found them, she whispered, “Go through the desk,” before she was taken away. She also grabbed a light coat and left the one she hoped still had the scraps in its pocket, though she felt the painful chill of December slap her in the face as soon as she walked outside and was shoved into the waiting black Volga.

The KGB officers brought her to Butyrka Prison, where she was charged with slander of the Soviet system under Article 190-1. In April, after three months in prison, she was taken to the Serbsky Institute, as she had feared would happened. There, she was examined by a commission of psychiatrists, including Professor Daniil Lunts, who had become infamous for liberally diagnosing dissidents with “sluggish schizophrenia,” a mental illness newly invented by Soviet doctors. Lunts joined in the conclusion that Natasha had a “slow progressive” case of this schizophrenia.

Her trial took place on July 7, in absentia—as a rule, mental patients were not allowed to be present in court proceedings. Natasha’s mother was allowed to speak from the stand. Weepy and exhausted, she made a plea: “If my daughter has committed a crime, sentence her to any punishment, even the most severe, but do not place an absolutely healthy person in a psychiatric hospital.” The defense lawyer’s only argument was that the Chronicle was entirely anonymous. No proof had been given that Natasha or anyone else had anything to do with creating or spreading the journal.

The court took no time to come to its judgment. It found her guilty, but of “unsound mind.” She would be placed in a “psychiatric hospital of special type for compulsory treatment.” The period of her “treatment” was left undefined.

In the months that followed, Natasha was placed in the hospital wing of Butyrka prison, while she awaited transfer to her ultimate place of confinement: the Special Psychiatric Hospital in Kazan. She knew what to expect: only a year before, in Issue No. 10 of the Chronicle, she had compiled a report on the institution, enumerating its horrors in a sparse style, exactly as they were conveyed to her by former inmates: “If the patients commit offences—refuse to take medicine, quarrel with the doctors, or fight, they are strapped into their beds for three days, sometimes more. With this form of punishment, the elementary rules of hygiene are ignored: the patients are not allowed to go to the lavatory, and bedpans are not provided.”

Now, she recalled the words of a poem she had written for her friend Yuri Galanskov, who had been similarly locked up in a psychiatric ward in 1966 and drugged: “In the madhouse/Wring your hands,/Press your pale forehead against the wall/Like a face into a snowdrift.” In Kazan, it would be her face, pressed and vanishing. The human rights reporter was now the reported, an item in Issue No. 18 recording: “On 9 January 1971 Natalya Gorbanevskaya was transferred from Butyrka Prison to the Special Psychiatric Hospital on Sechenov Street in Kazan (postal address: building 148, block 6, postbox UE, Kazan-82), where a course of treatment with Haloperidol has been prescribed for her.”

*

Natasha spent a little over a year incarcerated in Kazan, before her release in February 1972. Three years later, in 1975, she left the Soviet Union for good, moving to Paris, where she would live for the rest of her life.

The Chronicle, though, continued. There was a new editor, and there would be another, and another after that, until the early 1980s, when a fierce crackdown finally killed the journal. And yet, even after its fragile pages had ceased to circulate, the Chronicle’s mission somehow survived: within a couple years, the dissidents’ relentless focus on glasnost—what Lyudmila Alexeyeva called a “process of justice or governance, being conducted in the open”—would become the signature policy of a new Soviet premier, Mikhail Gorbachev, an effort at transparency he felt he had no choice but to implement.

The journal, which for so long had funneled and concentrated the dissidents’ efforts, was the vessel for this process. Out of samizdat they constructed a shadow civil society for debating and freethinking when their repressive environment made these activities impossible. In language crisp and unadorned, its insistence on truth had made it harder and harder to accept lies. That ineluctable logic ultimately proved greater than a superpower: it would soon undercut the totalitarian state and cause it to implode.

Years later, in 2013, Natalya Gorbanevskaya did return to Moscow. By then, she was seventy-seven years old, and Russia was more than a decade into Putin’s rule. The purpose of her visit was to join former dissident colleagues in recreating the 1968 protest in Red Square to commemorate its forty-fifth anniversary. Natasha and a group of nine friends unfurled a banner with the same slogan, “For Your Freedom and Ours,” and stood at the same spot by the stone slab of Lobnoye Mesto. They were instantly arrested by the police. A few months afterward, back in Paris, Natasha died.