Wherever I go, Greece wounds me.

—George Seferis

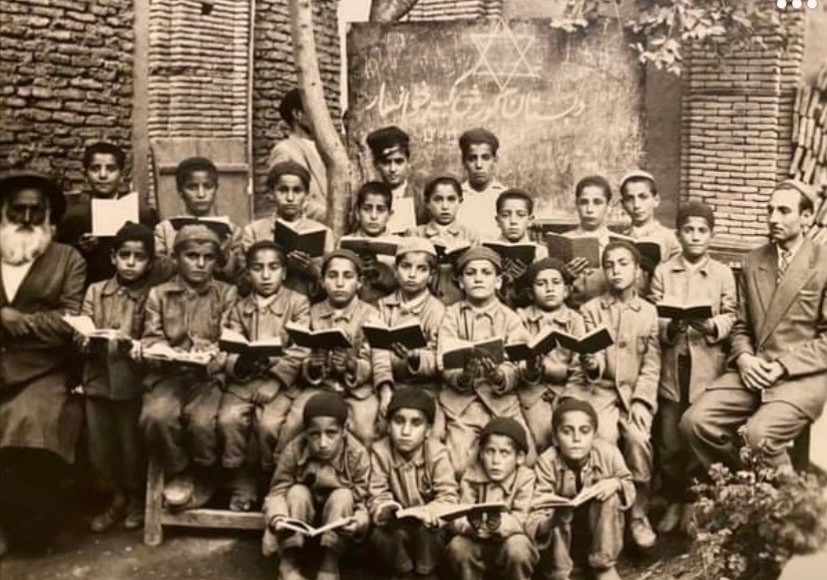

The video came as a link in an e-mail, the frivolous kind that weboholic relatives forward liberally. I was about to delete it when my eyes caught the subject heading: Your grandparents here!!!! It was a fundraising plea for a site that claimed to be an “unprecedented archive.” Click here to donate flashed at one end of the letter, click here to enter at the other. Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings had been playing in the background, which proved to be the perfect soundtrack for what was to come. And so I did what I advise everyone against: I clicked on a link in a random e-mail. A headstone appeared. On its uppermost edge, a Star of David was inscribed, under it a few lines of Hebrew, followed by Persian:

The death of the late paradise-bound

Khodadad Hakakian, son of Meir

on the 12th of Bahman, 1348

May he rest in peace

It took a few moments till I found my virtual bearings: the scene showed Tehran’s Jewish cemetery, Beheshtieh, where I had never been, and the headstone belonged to my paternal grandfather, who had died on February 1, 1969, and whom I had never met. The archive was, in fact, a repository of headstones photographed for the faraway relatives who can no longer visit their dead. The details of the image were scant, and yet, with eyes blurred by tears, I studied them. Dried leaves and dead grass lined the edges of the slab—cracked in some places, chipped in others. More than fifty years since it was first laid, this stone had endured, the last trace of the Hakakians in the land that had rejected them.

In the search box on the top corner of the page, I typed my grandmother’s maiden name. My only memory of her was faint. It was of the two of us on an amber summer afternoon, the air redolent of freshly watered juniper trees, in our Tehran courtyard, where we watched the windup bear she had brought me march in circles, beating a drum. Of that afternoon, nothing remains. Grandmother is gone. Our house was razed. The junipers were uprooted and replaced with a six-story apartment building. The surrounding community of friends and neighbors…none of it survived. That past has been so wholly erased that our presence in it could be denied altogether, except for a single mark: the headstones persist. Therefore, we were.

The image of my grandparents’ graves affected me in a way that the photograph of them on our mantlepiece at home does not. I had never really known them enough to grieve for them. But the tears came because the graves brought back memories of my father, who had never felt truly at home in America because, among other reasons, his parents were not buried here. The immigrant’s arrival in a new land, which is nothing more than the tail end of displacement, is often mistaken for a condition of being transplanted. But to be truly transplanted—a long and deeply visceral affair—means laying down roots, which happens most reliably when one gives birth to offspring in the new land or buries one’s elders in it. We are bereft when loved ones die, yet we draw comfort from their being in the ground we live on. It is why mankind’s most famous emigration story, the exodus of the Jews from Egypt, hasty as it was, could not happen until Moses had dug up the bones of his forebear Joseph from the bed of the Nile to carry them to the Promised Land.

Exile made an enigma of my father. He loved his adopted homeland for its freedoms, and yet he felt at sea here. When the weather allowed, he would spend most afternoons on the fourth-floor balcony of the Queens apartment that he shared with my mother, fussing with his few pots of geraniums. Then he would settle into his chair, as creaky as he was, and fix his gaze on the horizon. From that vantage, he had a sliver of the Manhattan skyline, and with that majesty in view, he would write poems about Tehran, about how everything had been better there: the air crisper, the water sweeter, the flowers more fragrant. Once every two weeks, he and his friends dressed to the nines—their pockets stuffed with poems, nearly all about Iran—and gathered at one of their homes to recite them to one another.

What cemented their bonds more than a shared homeland was a shared misery. The 1979 Revolution had cleaved their lives: the good time before it, and the ruin after. To speak of that trauma, they had their own codes. Following every greeting and due exchange of pleasantries, one would ask the other, “When will ‘these’ go?” The obscure pronoun masked the not-to-be-named evil that had upended their lives: the post-1979 regime. Or if someone inquired, “When did you come out?” they all knew to say their year of departure from Iran. To them, the only “in” was Iran. Everywhere else was simply “out.” In this ceaseless yearning for home, they made a band of misguided Odysseuses, who romantically overlooked the fact that their Ithaca had refused them. Compared with these magnanimous men, Odysseus was no hero. Dreaming of return is easy when a wife, son, dog, nursemaid, groundskeeper, and bed await you. My father and his friends dreamed of returning to a “home” where no one and nothing waited for them but their dead.

Advertisement

Exile had also disoriented my father. Whenever he was in my car, he would read the highway signs aloud and say, “What difference is there between Pleasantville or Washington Heights?”—pronounced “Vashington Heights” by the man whose lips had never needed to come together to form a “w” before—“Go north or south, east or west. I don’t care. No one is expecting me in any direction.” He felt unmoored. And he felt purposeless. Each time one of his friends died, he would dutifully say, “It’s my turn next.” It was as if they had all come to America to perform one final parental act of sacrifice for their children: to become martyrs to the cause of belonging.

A refugee’s physical jet lag takes a few days to resolve, but the emotional one can take months, even years, to resolve—or, as my father proved, never. He lived simultaneously in two time zones. One was that of his adopted city. The other was the time zone of his mind, which might as well be called the Standard Time of the Displaced. In a profound sense, the past was all the present my father knew.

No one knows what is a reliable predictor—race, class, ethnicity—of an immigrant’s adaptability. But the immigrant’s use of tenses, his view of what was, is, and can be, reveals more about how he will fare: the way he speaks, or refuses to speak, of what he has left behind; the way he lives, or does not live, in the here and now; what he chooses to remember or to forget.

My father had many critics who reproached him for his “maladjustments.” But to me, they were all virtues. Every time I went to visit him, the elevator ride took me from the lobby of the building in Forest Hills, Queens, and somehow delivered me to Yousefabad, Tehran, by the fourth floor. The door opened and the sound of Persian traditional music, entwined with the smell of stewing herbs, washed over me. Above the love seat in the living room where he sat to watch television, two paintings hung between a needlepoint portrait of Moses holding the Ten Commandments: one of the tomb of the poet Hafez, the other, a cityscape of Isfahan. In my early twenties, when I struggled to answer people’s incessant, intimidating questions about my identity—Was I Jewish or Iranian? Iranian or American? Was my homeland Iran, Israel, or America?—the integrity of my parents’ apartment guided and reassured me: I was an amalgam, the child of naturalized US citizens in the Tehran of Queens, where Hafez and Moses were read with equal passion on different occasions.

Memory pales with the passing of years. Then the irreversibility of exile, the impossibility of returning to revisit the familiar sites and people, frays its fabric. These things may be the usual wear and tear of every life of the émigré. But add to this a theocratic tyranny, which through its own “cultural revolution” expends boundless resources to scrub inconvenient facts from the record in the name of eliminating “vice,” and holding onto the truth of the past becomes more than a matter of remembering. It is a matter of preserving and guarding an endangered, though immaterial, artifact.

A stubborn sentry at the gates of our history, my father and his facts never budged. The past was etched in his memory as indelibly as the inscription on his parents’ headstones. He knew what he knew, loved what he loved, had seen what he had seen. And while old age had ravaged his eyes, his view of the truth would not be clouded, which is why whatever doubt I had walked in with vanished by the time I left.

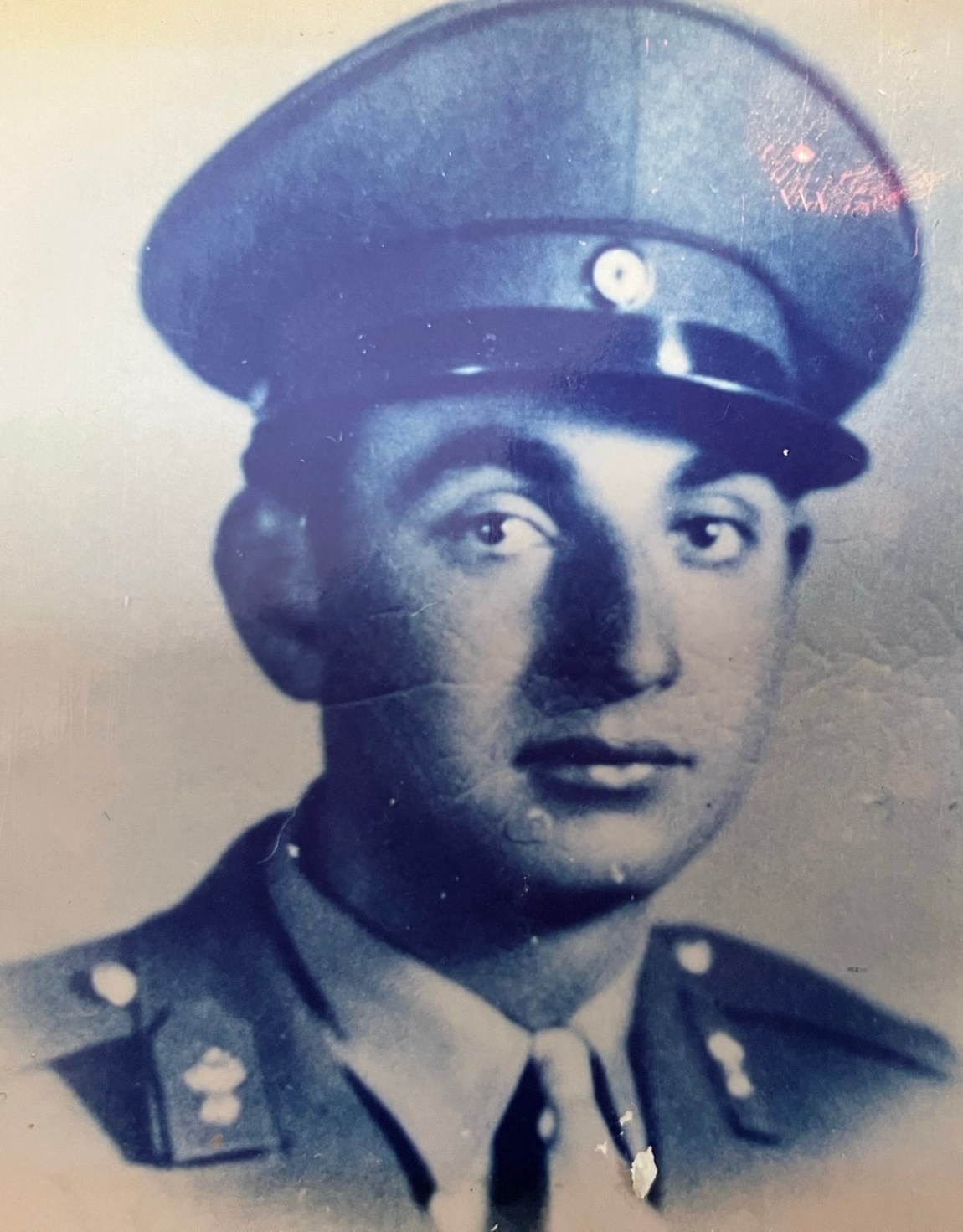

If CNN was on, it was on mute. My father, who had served in the Iranian army and risen to the rank of second lieutenant, and who had educated thousands of students during his long career as a school principal, did not need cable TV pundits to tell him what was happening in Iran, or what he should think about elections or protests unfolding there, but he did appreciate seeing the silent B-roll. In America, where I no longer needed him to protect or provide for me, he was the lamp I held up to my dim recollections in the catacombs of memory to verify the details. His maladjustments, in retrospect, were the requirements of his new job after arriving in America: to engage with his adopted homeland more fully would have meant leaving his post as watchman.

Advertisement

My father died in 2017. Now that he is buried here, he has rooted me in this land, just as he had rooted me in the other land while he was alive. After his death, I wondered how I would cope with the loss of my memory-keeper, my rock. Then those two other stones appeared, and seeing them reminded me that some bonds can never be severed, neither by departure, nor by death.