“A writer who draws” is how Saul Steinberg described himself. Twenty years after his death, the graphic artist remains best known as the swiftfooted and bonkers satirist behind over eighty covers for The New Yorker. In the beloved artist catalogs he assembled for Viking and Knopf throughout his career, he played with the slippery ability of words to replace (and to reduce) complex experiences. What does the feeling of duration look like? In answer, in his book The Inspector (1973), he stacked cartoon words in a tower, big to small: Year, Month, Day, Hour, Minute, Second, with a flag, Now, flapping at the top. And the feeling of ambition? For Steinberg, it looked like a businessman speeding down a mountain on a Yes-shaped wagon—headed straight for the But-shaped wall below.

The title of his rich new retrospective at Pace Gallery in Manhattan, “In the Library,” brings into sharp relief the problems of representation he dealt with in his cartoon allegories. Focusing on sculpture, a medium that absorbed his later years, the show is small but tartly chosen. Its installation in Pace’s working library, opposite a wall of reference books, cunningly puts the punchline before the setup.

Among the many pieces on display are books themselves, or approximations of them. Steinberg whittled paperbacks from blocks of wood, running a crude pencil around the outer edge to suggest a gathering of pages and leaving just enough pucker in the middle to imply a binding that has been cracked open and laid flat. The pages in these books contain gibberish text or imitations of the faded engravings in an antique volume. (Steinberg had an extraordinary ability to replicate handwriting without a single legible character. Try it—it’s harder than you think.) His “notebooks” from 1989 pair Polaroids on the left pages (shots of himself and of a street scene) with slapdash pencil copies of these photos on the right.

While the Pace librarians squeak their ladder cart across the room to retrieve a title from the top shelf, Steinberg’s tomes make a parody of their good labor—a gentle mockery of reading. Scrutinizing these wooden books, you are admitted to a joke in some foreign language about how meaning gets inferred from print. The confusion they inspire, that an implied correspondence between something lived and something described does not quite fit, suffuses the rest of the show down to its tiniest details.

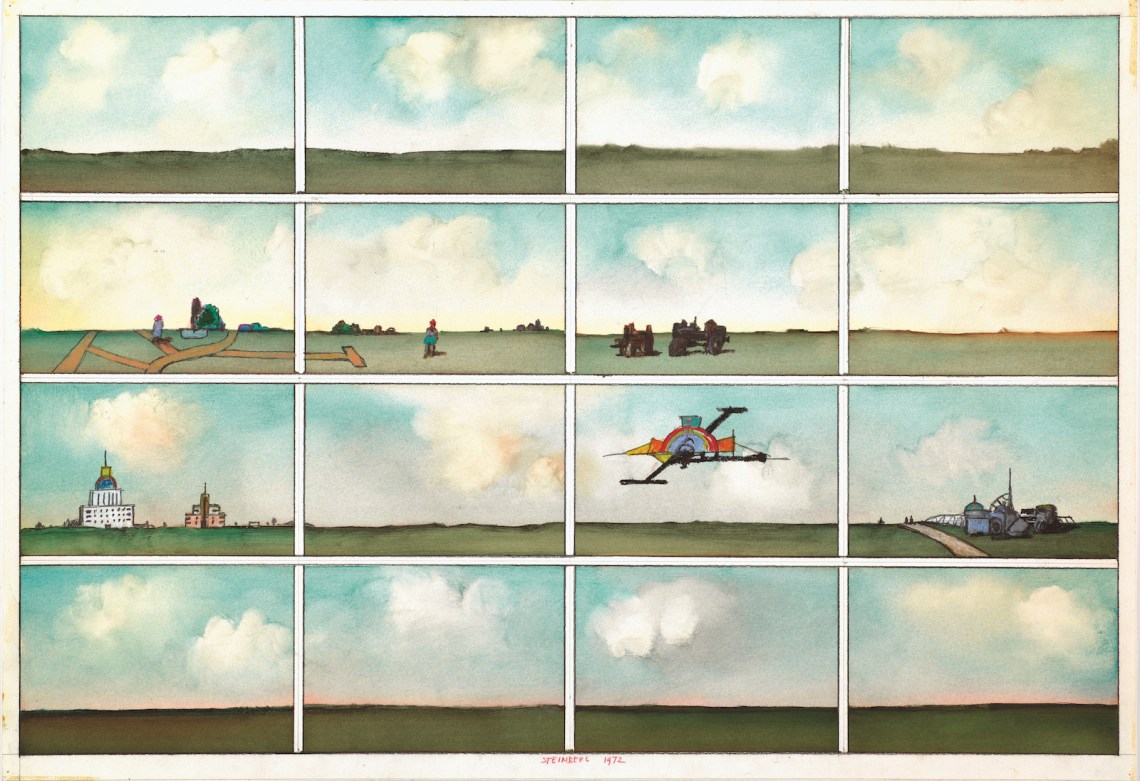

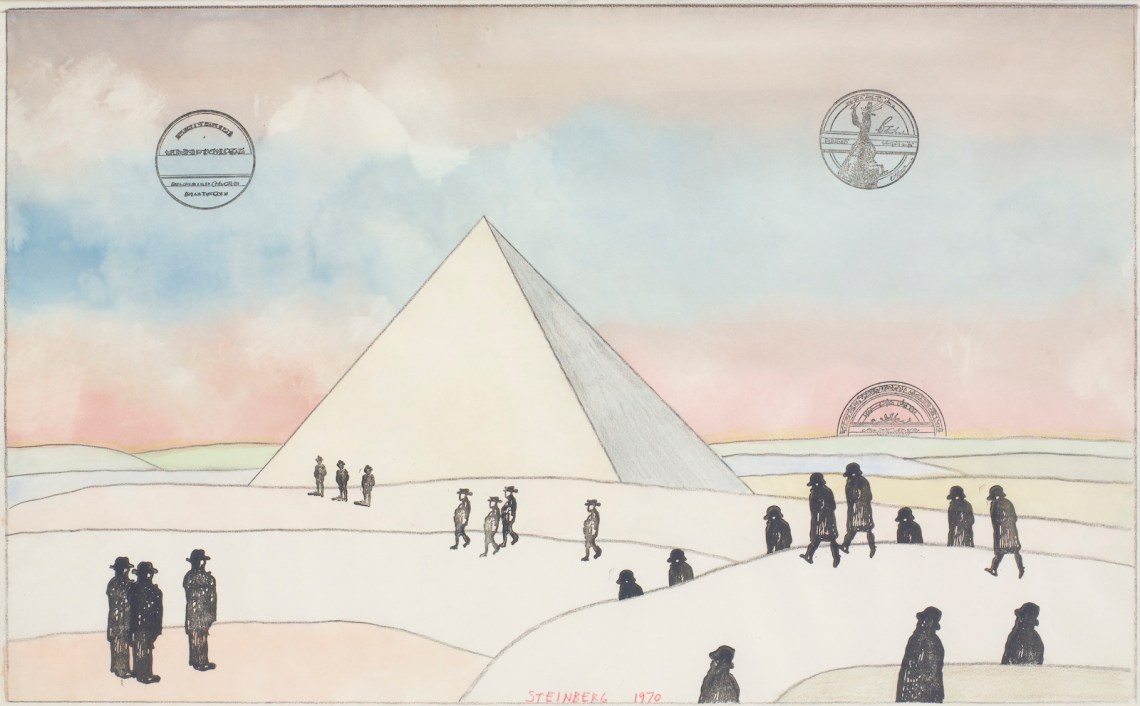

This dissonance has always been an effect of Steinberg’s mystifying “post card” landscapes, of which several are on display. In Sixteen Landscapes (1972-1979), a grid of carefully rendered oils, the clouds appear photographic from a distance, but beneath these skies, clumsy skyscrapers and vehicles intrude in graphite. They look like an ideal of the word “city” dreamed up by someone who has never been to one. While the faux books pull you, the viewer, into some simulation of your own life, these works on paper, with their clash between the observed and the conceived, allow you to eavesdrop on someone else’s frustrations with reality.

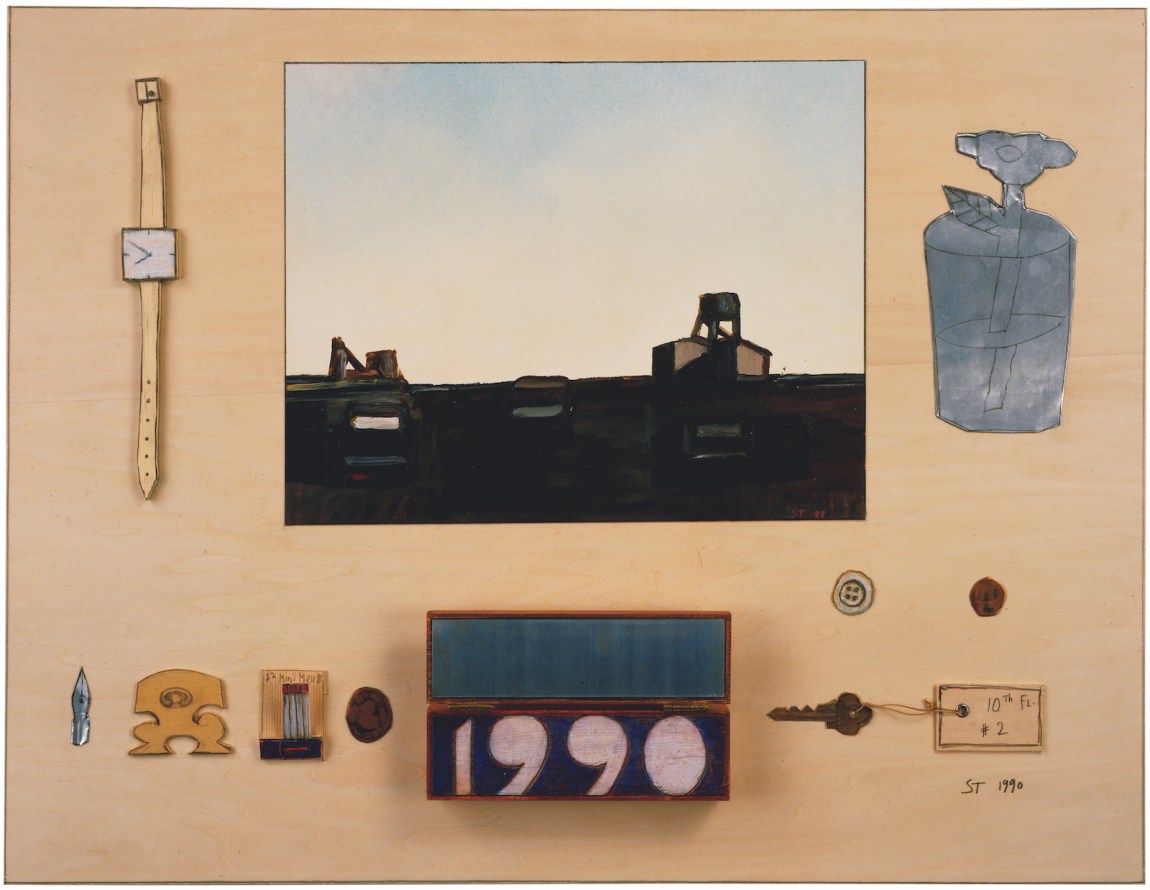

Displayed singly or in assemblage are a bedroom’s worth of household items. Sculpture invigorated Steinberg during a creative block with paper: “This new passion for wood—what fragrance!” he said in 1973 of his Table Series, “In working on them there’s only pleasure, the mind is at rest, it’s the happiness of a horse.” Fashioned mainly of wood and paint, each object in the show wears an endearing sense of purpose: manhandled pencil nubs, battered nibs, brushes caked in paint, slivers of lemon and cucumber articulated with seeds and skin, a matchbook unfurled and ready to be peeled for a strike, a motel key and its fob for the tenth floor, room two.

Summer Table (1981), the most immersive piece in the room, is a full-scale drafting table arranged exactingly with make-believe studio wares. On the table, Steinberg has inscribed halos in pencil around his piles of stuff, his paint cases, brushes, picture books, a painting-in-progress, an old tomato can full of his tools—instructions left visible for their placement in the installation’s reassembly. When you spend time in another person’s space, he reminds us, its accumulations appear so intentional as to possess their own alien confidence.

The table is worth the trip on its own, not just for the visual smorgasbord but for the fresh way of seeing it offers. A wooden briefcase (composed of segments of board joined by a hinge) lies open, and from its lid hang geometric stalactites of different sizes and lengths, facing corresponding cubby holes in the base. If only you could shut the lid and unite them. Similarly, across the table, an artist’s palette is inset with footprints that await chunky prisms of wooden “paint.”

Advertisement

By making such nursery toys out of the tools an artist might use to describe his world, Steinberg takes a swipe at the whole absurd enterprise of professional adulthood. Into a single corridor of objects, curator Arne Glimcher has distilled one of the artist’s favorite tricks: Steinberg reduces you to that inviting but unsettling preverbal suspicion that the visual realm might not yet have a name but nonetheless obeys some system beyond your reach.