On February 11, 1982, in front of a live studio audience, Man Ray sat on top of David Letterman’s desk and lapped milk out of a drinking glass. The Weimaraner, named for the dada photographer, was a guest on Late Night with David Letterman with his owner and collaborator, William Wegman. Wegman showed clips of films he’d made featuring Man Ray, including one in which he grades the dog’s spelling abilities (Man Ray spells “park” right, but writes “beech” instead of “beach”). During the interview, Letterman asked Wegman if he had a replacement lined up for when Man Ray died. Wegman replied: “I have a tomb, and I think I’ll be buried along with him.”

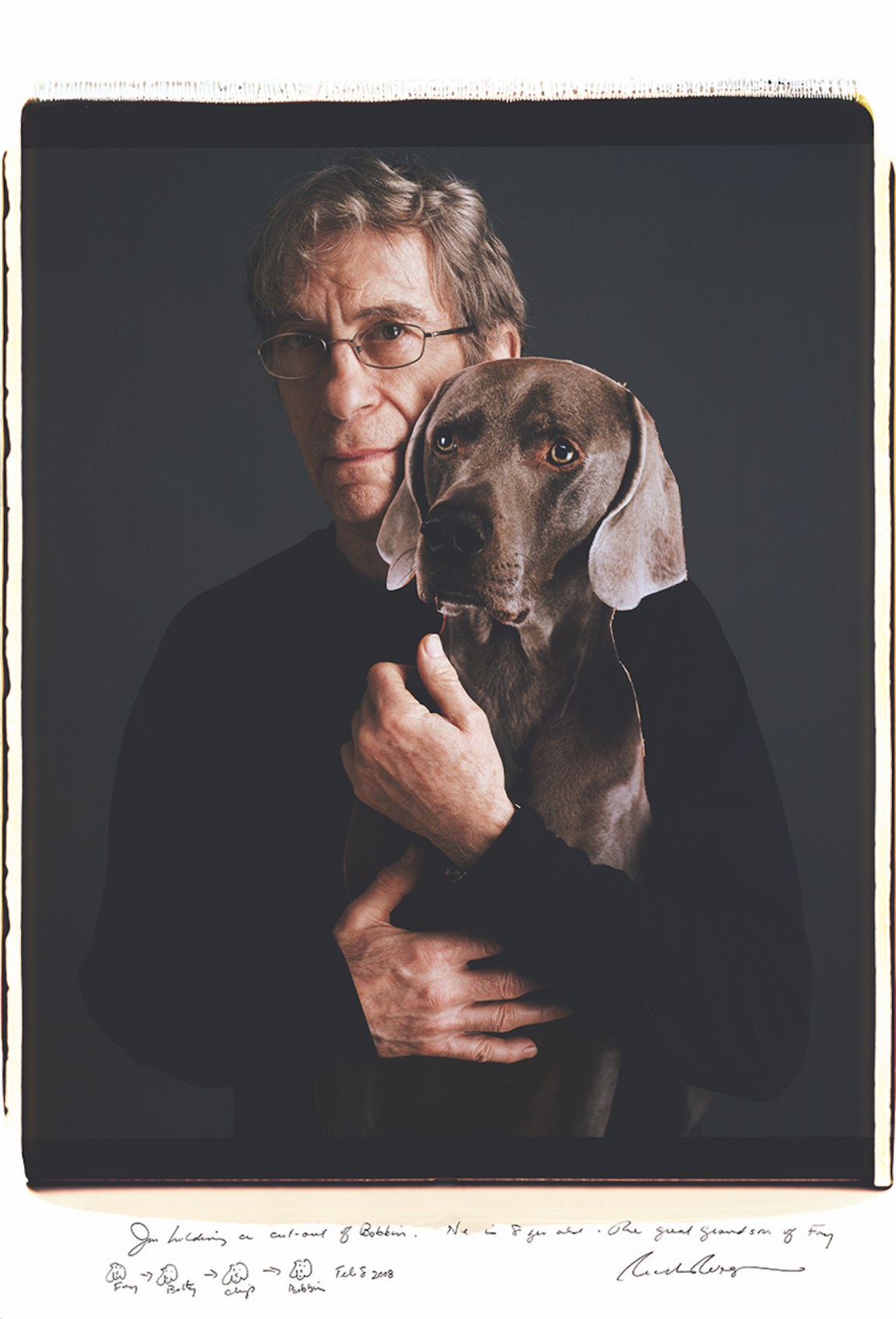

The appearance on Letterman came during Wegman’s early forays into video art, which had made Man Ray famous internationally. Though he began his career in fine arts, getting a BFA and MFA in painting, Wegman quickly turned toward conceptual art and photography. While teaching at the University of Wisconsin between 1968 and 1970, he acquired a video camera that the school used to record lectures (Letterman on that acquisition: “Stole it, eh?”) and began making short, experimental films. He moved to Southern California in 1970, where he adopted Man Ray and began including him in his videos. Man Ray would die the year of the Letterman interview, but Wegman eventually began working with another Weimaraner, Fay Ray, as well as Fay’s offspring. Fay is best known to a generation reared on Sesame Street in the late 1980s, in skits featuring her in costume and Wegman’s deadpan voiceover.

Though Wegman’s films and photography with his dogs are his best-known work, he has an entire other oeuvre that has remained mostly unseen: a practice of visual and textual humor that is collected in the book William Wegman: Writing by Artist, edited by Andrew Lampert. Selections of this work, along with videos and recent paintings by Wegman, are on view at Sperone Westwater in a show of the same title, also curated by Lampert.

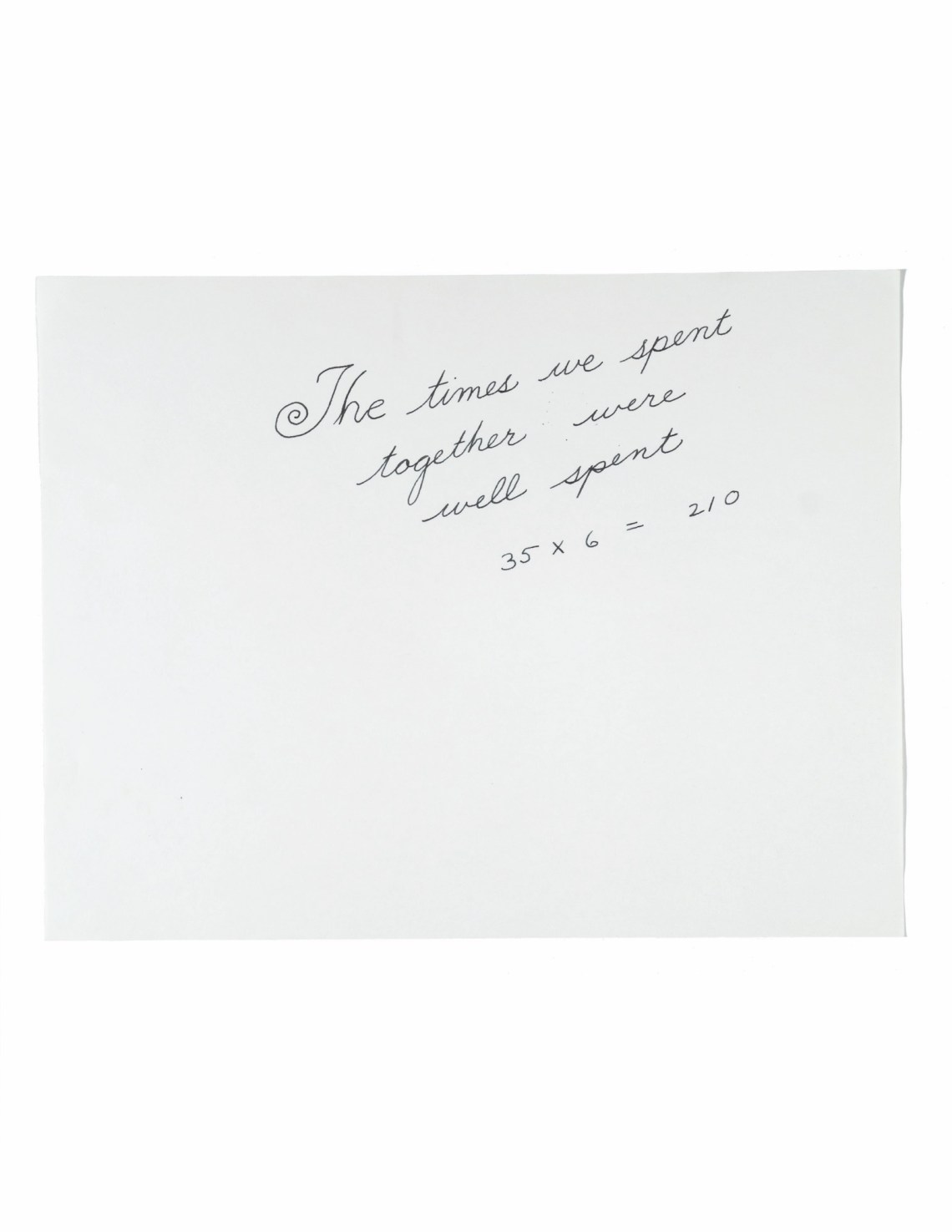

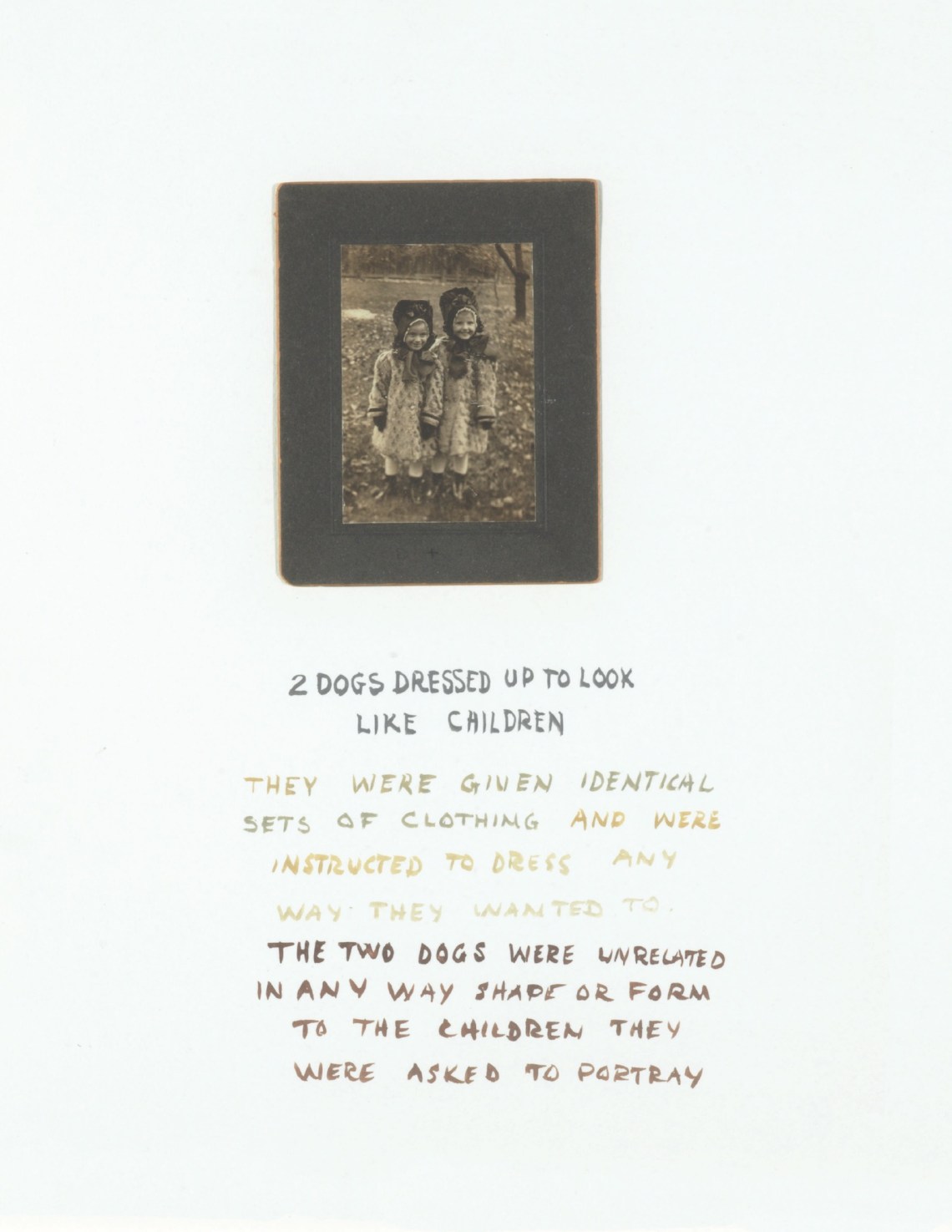

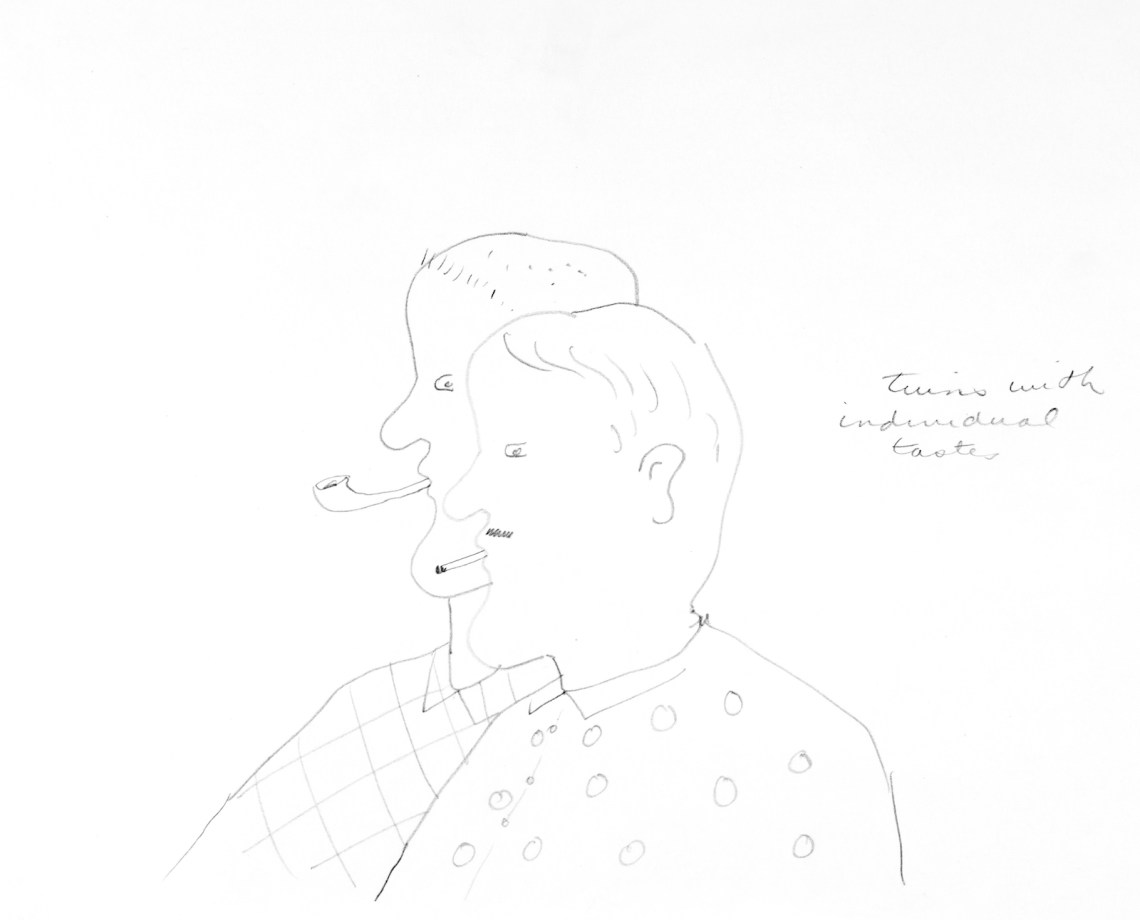

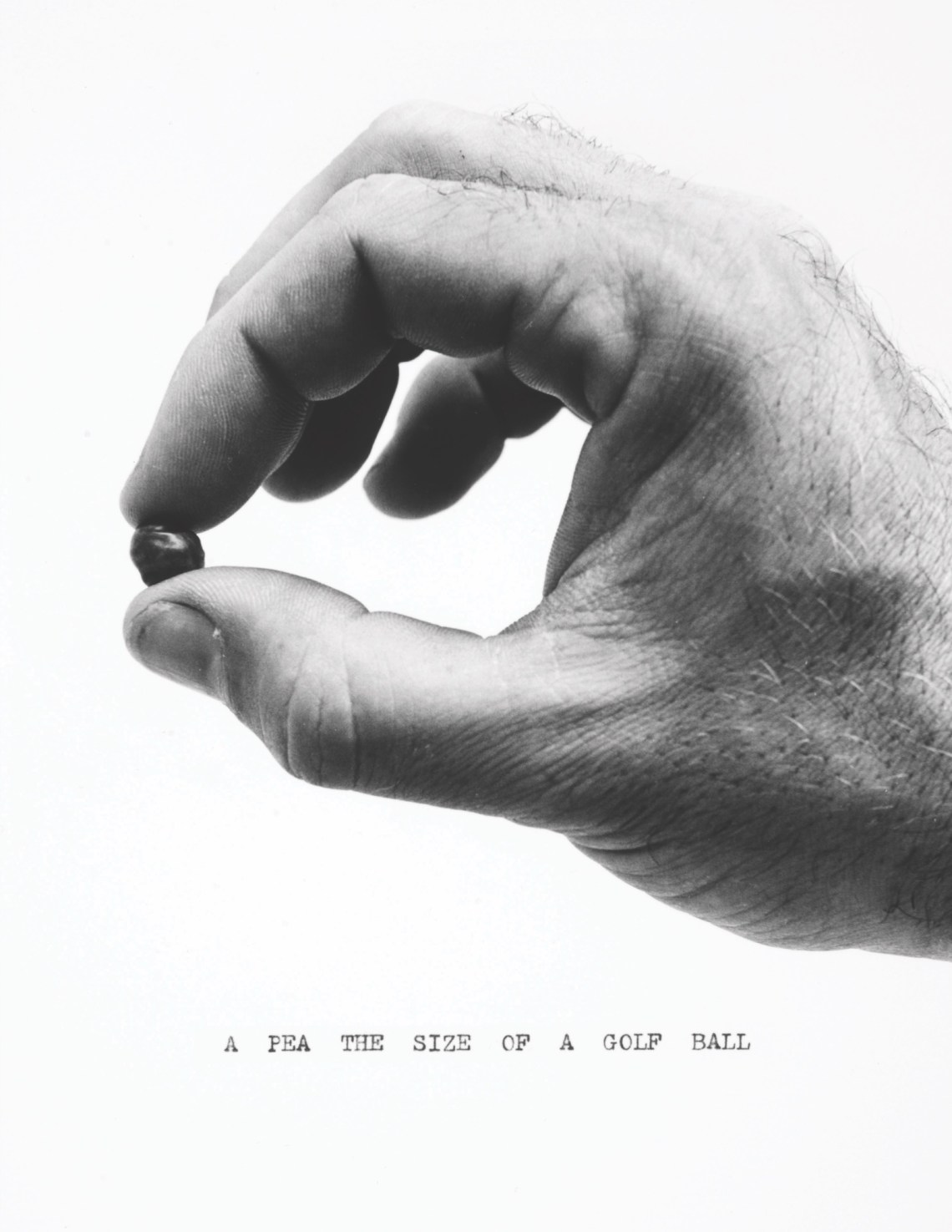

Clocking in at 352 pages, the book is made up of materials primarily from the 1970s and 1980s. There isn’t a page number in sight after the introduction, and at times it can feel less like a curated volume than a self-guided rummage through Wegman’s archives. This looseness is by design, as Lampert freely admits: “No attempt whatsoever has been made to place works in chronological order because there is no way to conclusively know when they were created.” More production work could have been done to brighten or darken some of the scans so the reader doesn’t have to squint at Wegman’s pencil lines and paint strokes. But these are small matters when you’re looking at so many treasures. Page after page of text, some typed, some written by hand, and images drawn, photographed, and painted reveal again and again Wegman’s seemingly bottomless inventiveness and humor.

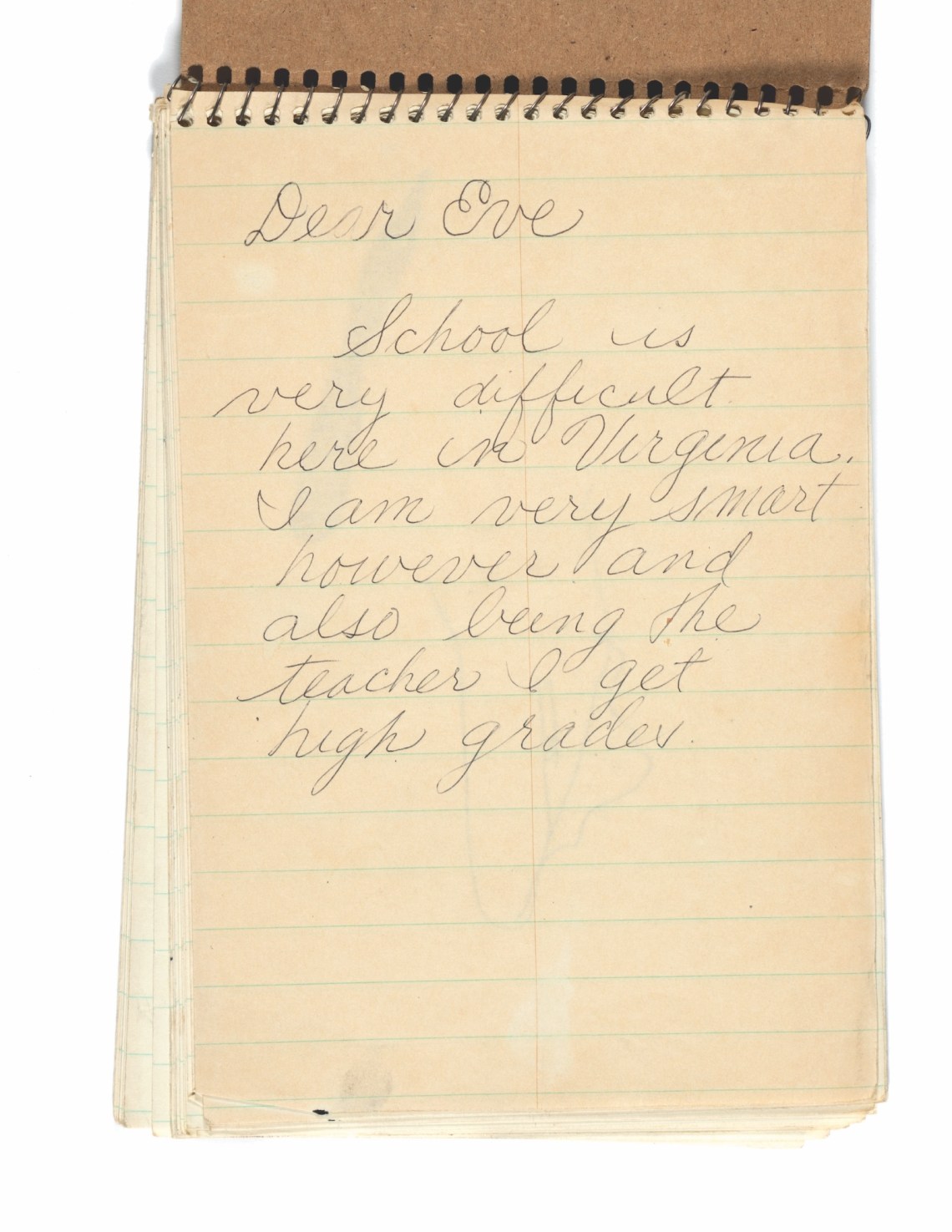

Each of Wegman’s texts is a small world, easy to read in the same monotone he uses in his films with his dogs. One handwritten note delivers an insane twist:

Dear Eve

School is very difficult here in Virginia. I am very smart however and also being the teacher I get high grades.

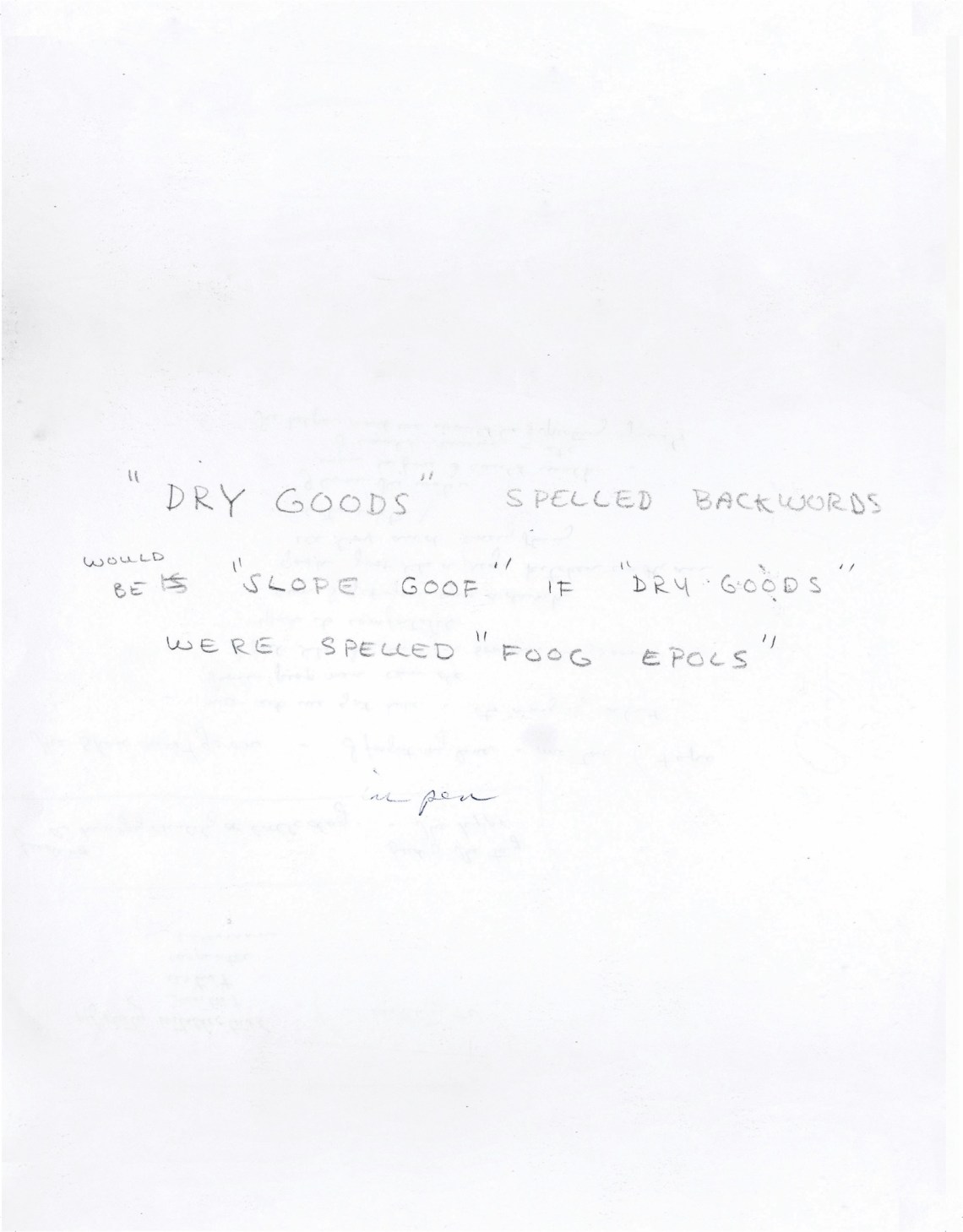

In another, he drops a truth bomb with the smug confidence of someone who does all their own research online:

“DRY GOODS” SPELLED BACKWORDS

ISWOULD BE “SLOPE GOOF” IF “DRY GOODS” WERE SPELLED “FOOG EPOLS.”

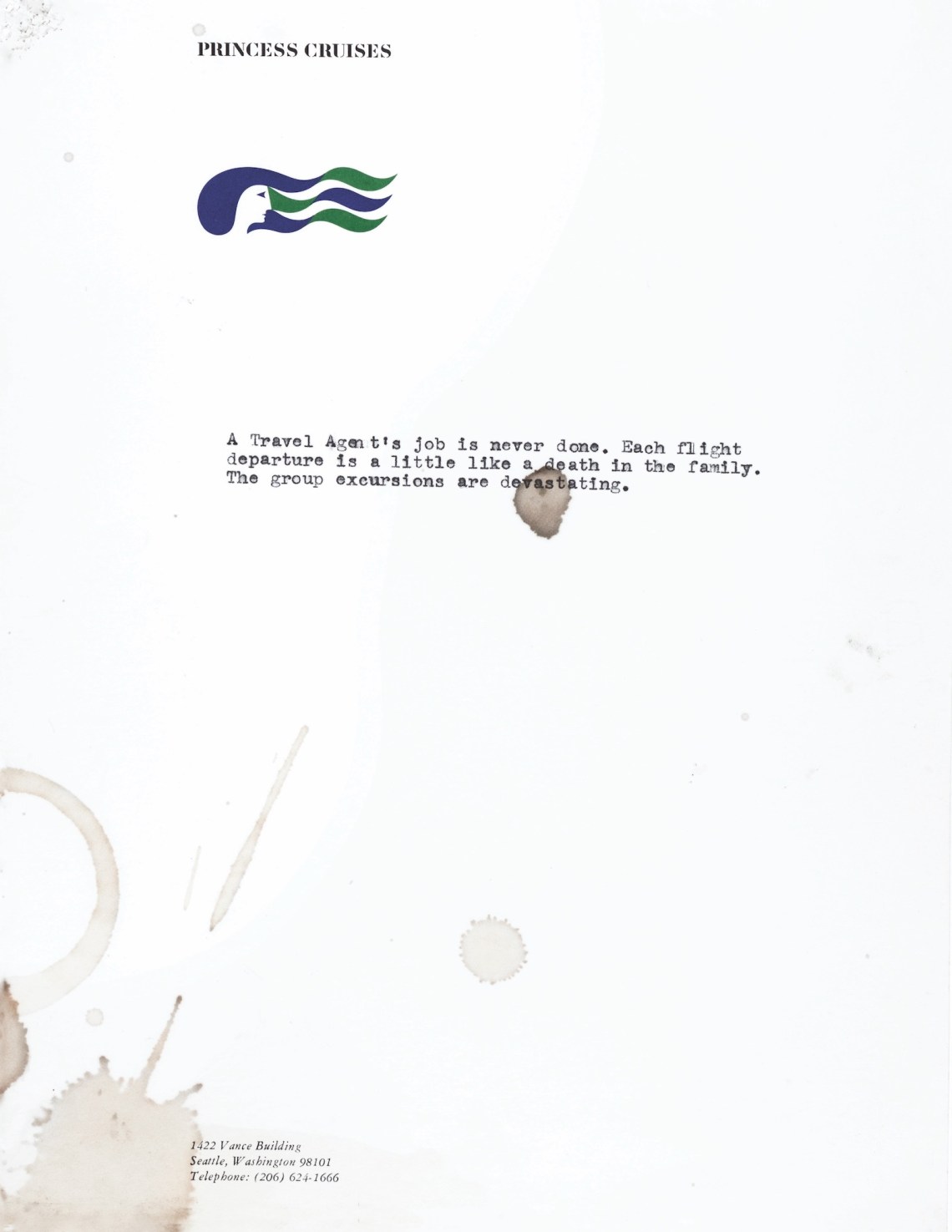

Wegman, delightfully, got his hands on a stack of Princess Cruises stationary. The corporate logo, a woman gazing to the right, her green and blue hair blowing in the same direction, lends his typewritten assertions a demented authority. Some highlights:

A Travel Agent’s job is never done. Each flight departure is a little like a death in the family. The group excursions are devastating.

Are you the man they call TRACTOR? I was told to look you up when I got to the city and that you might be able to

move some stuff for me.plow my garden and help me move some stuff plow something for me

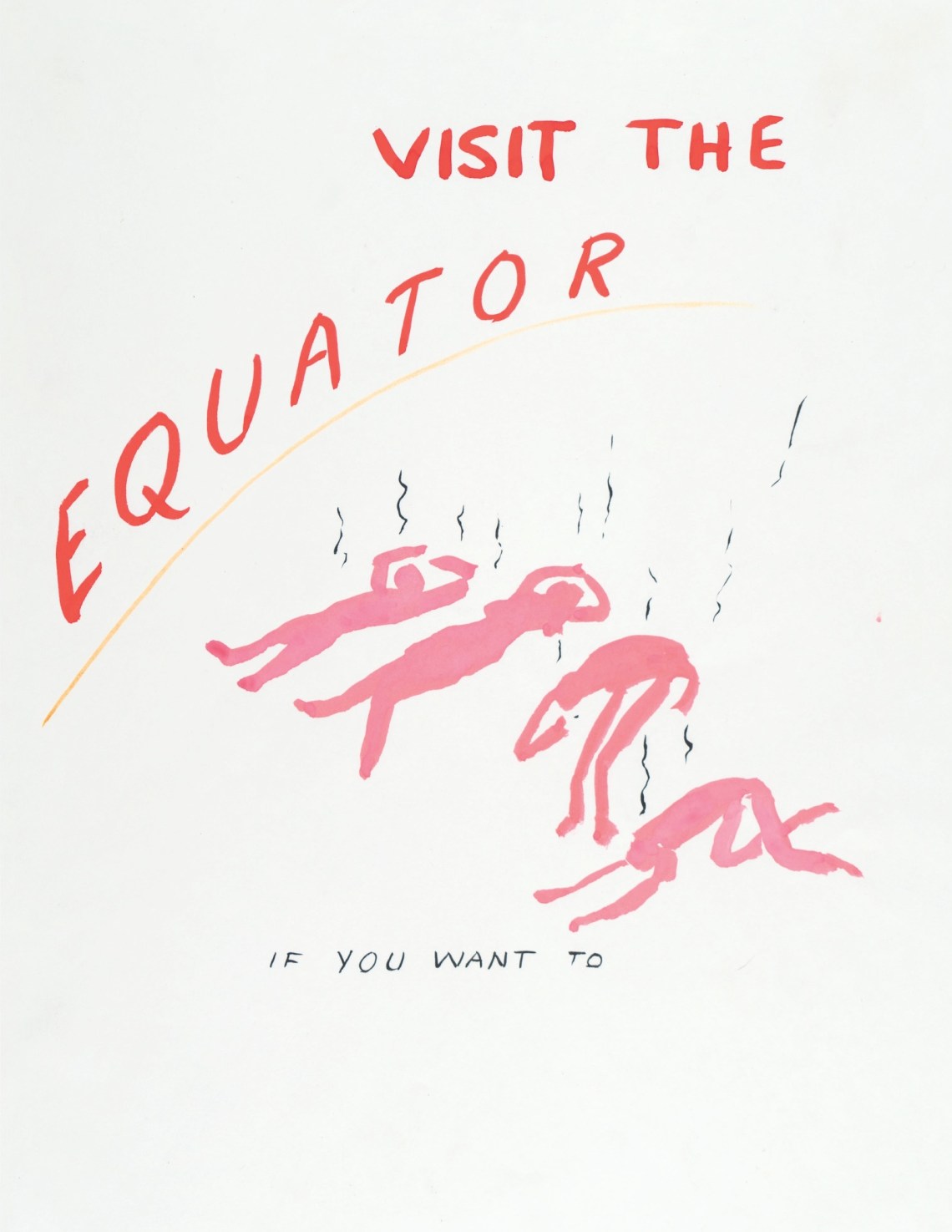

This flat, non-sequitur humor anticipates the unplaceable tone of humorists like Jack Handey, whose signature “Deep Thoughts” ran on Saturday Night Live in the 1990s (a classic: “Instead of mousetraps, what about baby traps? Not to harm the babies, but just to hold them down until they can be removed.”), and the meme-like scenarios of Chris (Simpsons artist). That same fearless defiance of reality and logic appears throughout his drawings, even in his loosest work. In one hand-painted composition, the text reads “VISIT THE EQUATOR / IF YOU WANT TO” while pink figures writhe on the ground in the heat.

Advertisement

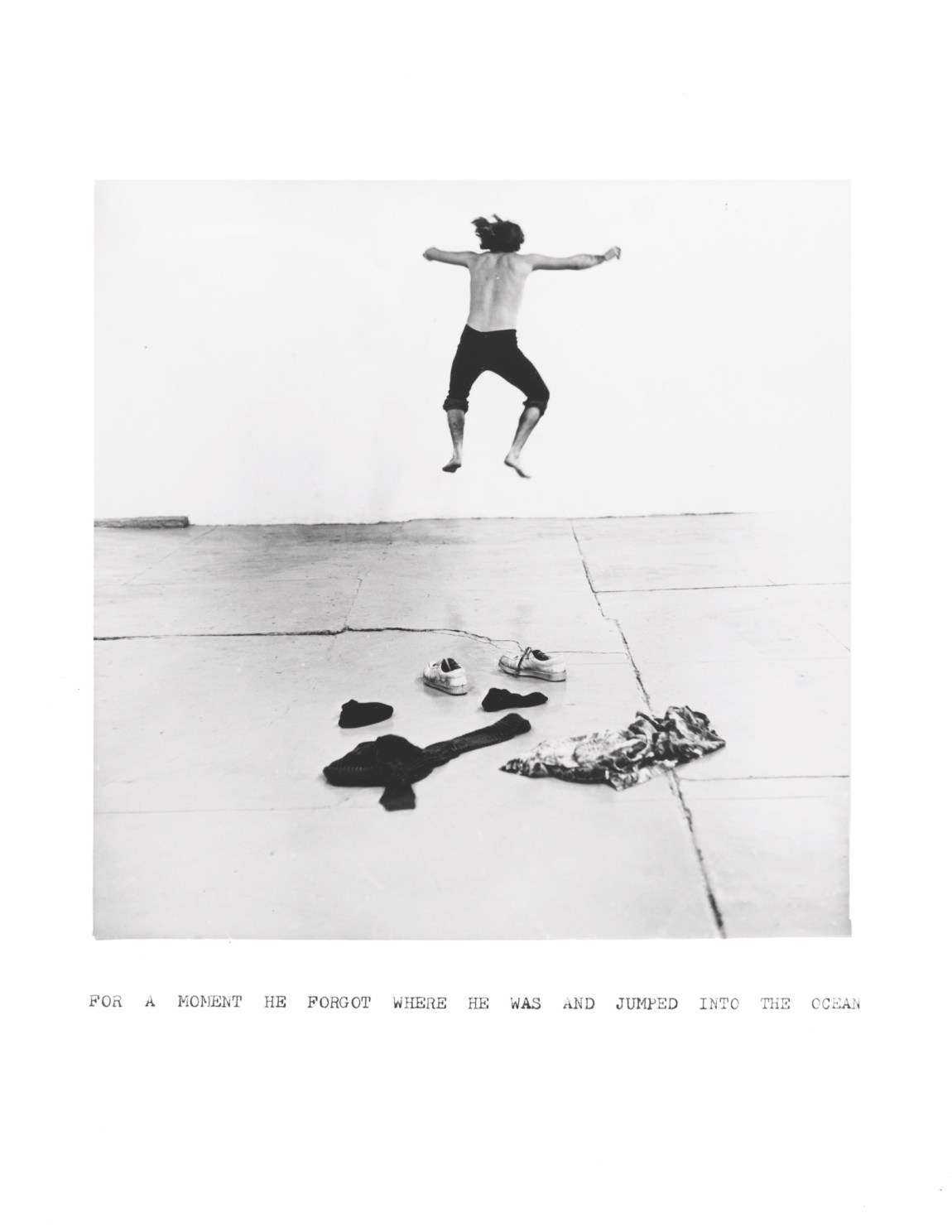

In the collection’s introduction, Lampert reveals his (and maybe Wegman’s own) unease with what to call these combinations of images and text. He cites Gary Larson and New Yorker gags, but locates Wegman’s result “somewhere between a cartoon and a koan.” It’s okay to call these what they really are: most of this book is full of joyfully weird cartoons. In this medium Wegman rivals absurd greats like Glen Baxter, David Shrigley, and B. Kliban.

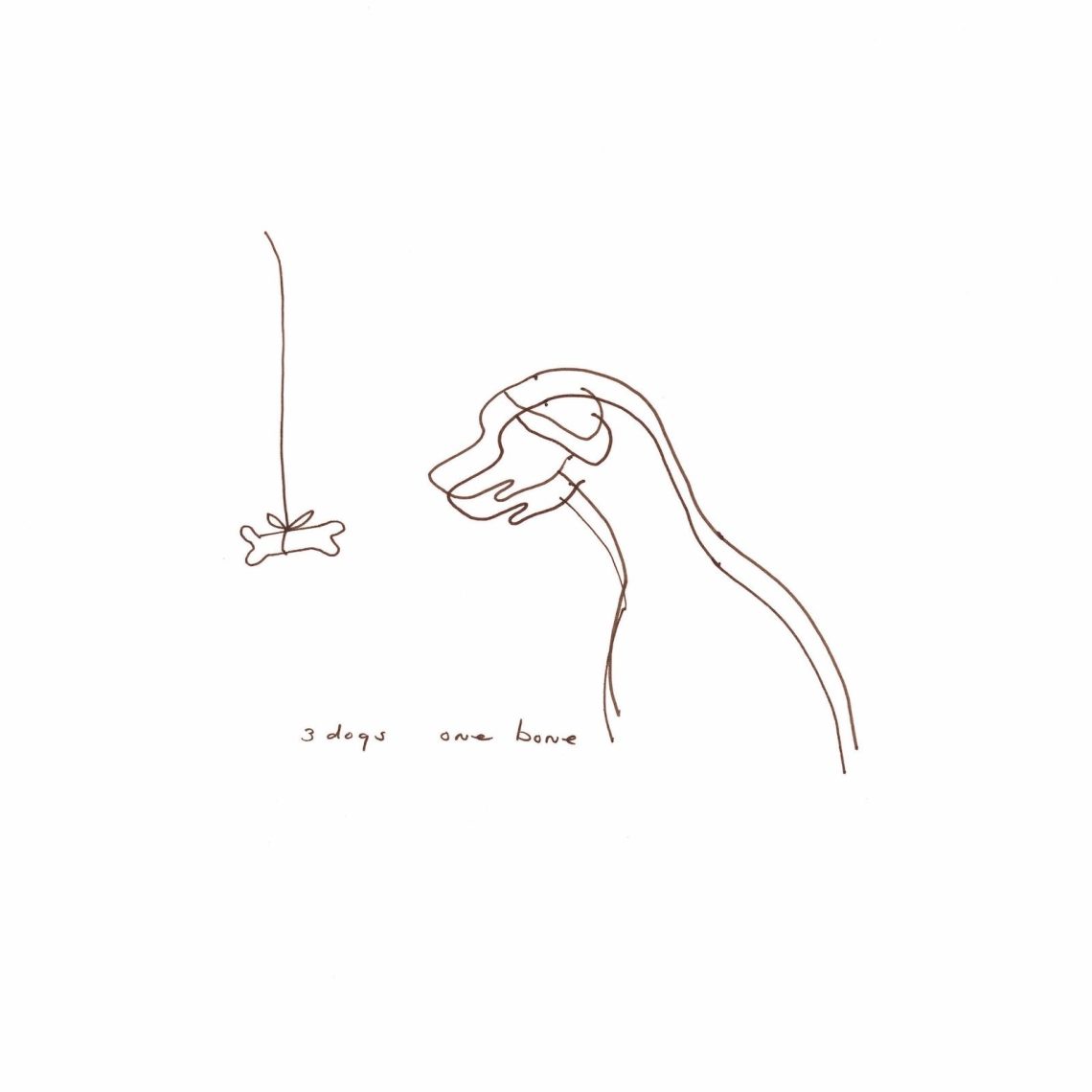

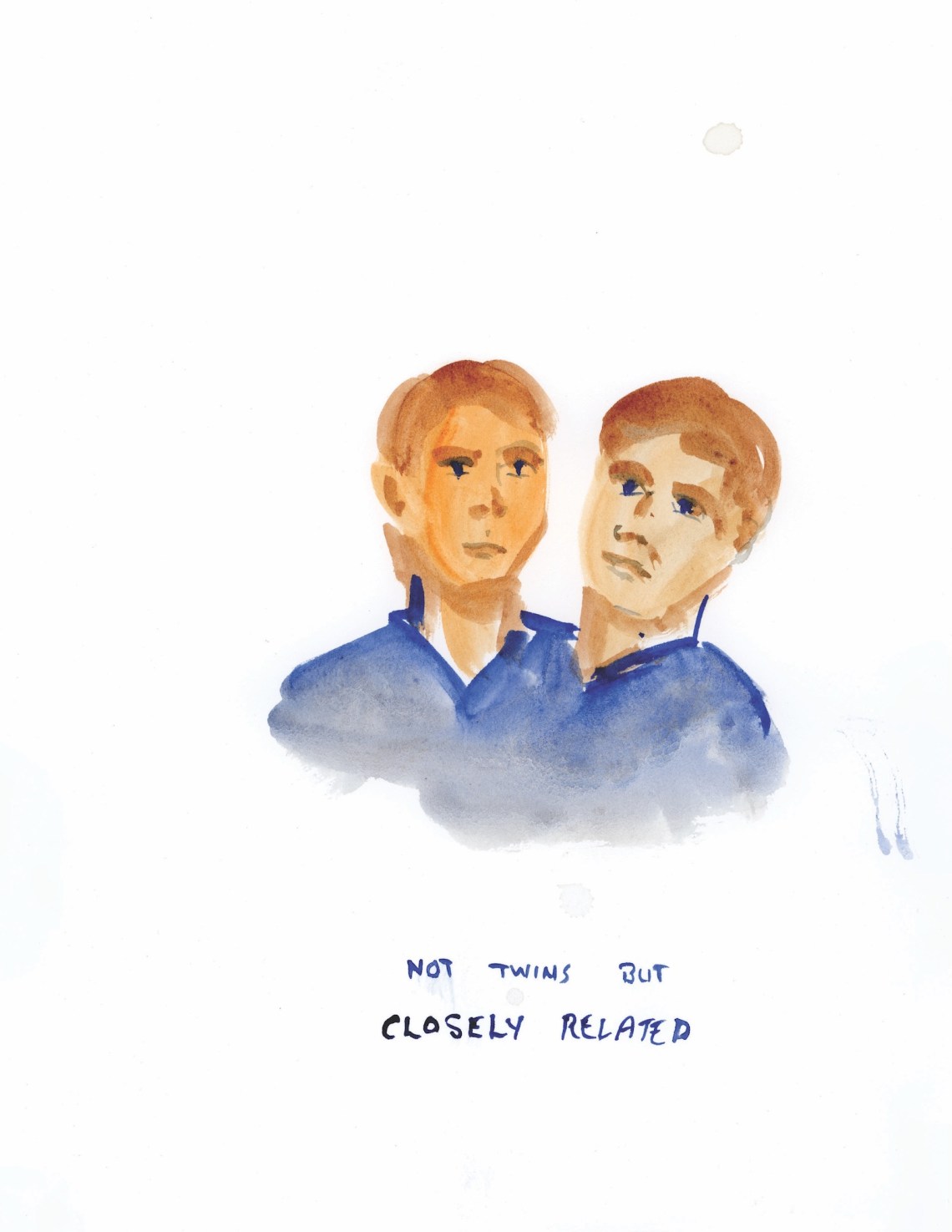

Like other fine artists such as Saul Steinberg or Faith Ringgold, Wegman makes good use of the tools of comics and cartooning to convey the power and hilarity of his visual imagination. A two-page spread depicts a “sandwich beverage” (a scribbled sandwich with a straw sticking out of it) and on the facing page a watercolor diagram of a BLT being assembled, with plywood in place of the bread. Another image, of two blue-eyed, brown-haired boys wearing matching blue shirts, is captioned “NOT TWINS BUT CLOSELY RELATED,” as though to reassure against a Shining-style situation. An unfinished portrait of a woman announces with that Wegman-brand certainty: “Does this look like you? As far as I’m concerned it does.” Facing an enormous public sculpture rivaling Hudson Yards’ Vessel in monolithic dumbness (“5 MILLION DOLLAR SCULPTURE / PEOPLE LOVE IT”), onlookers announce their approval: “great,” “cool,” “awesome.” One apparently Italian onlooker shouts from a rooftop: “Bolissima” [sic].

Wegman often offers solutions to problems that don’t and have never existed. In one cartoon, a boy in a sweater gestures to a floating sheet of paper that says “Hi Folks: My name is Hans Pototow. Just think of ‘Hands-Potato’ and it’s easy to remember. I am a newsboy.” (With his other hand, he gestures to a sheet of paper that says simply, “NEWS.”)

Unnecessary problem solving is a rich tradition in cartooning, and the book leans into Wegman’s particular approach, opening with a design for a device that screams “better mousetrap”: a dust pan with arrows pointing toward dust, grip, and a small piece of cheese, while a mouse gazes toward the arrangement. What self-described “paintoonist” Jerry Moriarty once wrote about Ernie Bushmiller, the creator of the much-beloved Nancy comic, rings true about Wegman and his work, too:

Bushmiller was a systems inventor. When his brain couldn’t comprehend an established system, he created a new one to replace it…. Nancy’s kitchen chair is too low for the table, so she puts each chair leg in a high heel shoe from Aunt Fritzi’s closet. Sluggo can’t get a square mirror to hang straight on the wall, so he hangs a round mirror. Nancy makes do, Sluggo makes do, and Ernie Bushmiller made do. This went on every day for 50 years.

Wegman makes do as well, through an endless array of ways to think about and reimagine the world. And we’re lucky to have them at all: he lost a significant amount of his work to a studio fire in 1978. This loss gives potency to another observation of Lampert’s, that Wegman’s compositions “possess a sense of immediacy, as if the whole thing was forced out of Wegman’s head via his hand before the idea could evaporate.” Writing By Artist can serve as a guide for other artists who are willing to venture into humor and cartooning on the sly.