Each day my phone greets me with images—from two years ago, two weeks ago, eight years ago; my toddler, my ex-husband; my toddler as a baby, my mother, a friend I miss, a friend I don’t speak to, my grandmother at her wedding in 1951; my current husband, our wedding. I encounter myself as well: my face before the pandemic, before pregnancy, then during and after.

These images come like the beads of a rosary. Sometimes they cluster around a theme, something the algorithm can recognize: veils, the round shape of a baby, mealtime. Other times I can’t detect a theme, although they’re my private jpegs. They don’t need to cohere, they make a ritual, a clock, regardless of who took them, when they were taken, or where. Sometimes they wound: dead friends, old apartments. Worse is when they are degraded by association with my digital detritus, outtakes and errors woven in. A photograph of a photograph, screenshots, a face out of focus. Together, high and low, stripped of context, these images can shock all the more for being out of order.

This is the punctum of the digital. For Roland Barthes, in his writing about film photography, the punctum is contained to a single image, that “sensitive point” in a photograph that pricks and wounds. Pain, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. We cannot assume my punctum to be yours, or Barthes’s, for that matter: “To give examples of punctum,” he wrote in Camera Lucida (1980), “is, in a certain fashion, to give myself up.” As with retelling dreams, identifying the punctum is both too private and too boring. On the smartphone, however, that wound arises from a set of images, grouped like this just once, until the algorithm decides to include them in another collage. It’s out of my hands, except that I hold the archive in my palm, a bizarre feeling. The sensitivity comes from their serial quality, a false belonging sent across swipe after swipe. “How do you,” Lynn Spigel asks in TV Snapshots, her latest book, “make the punctum searchable?”

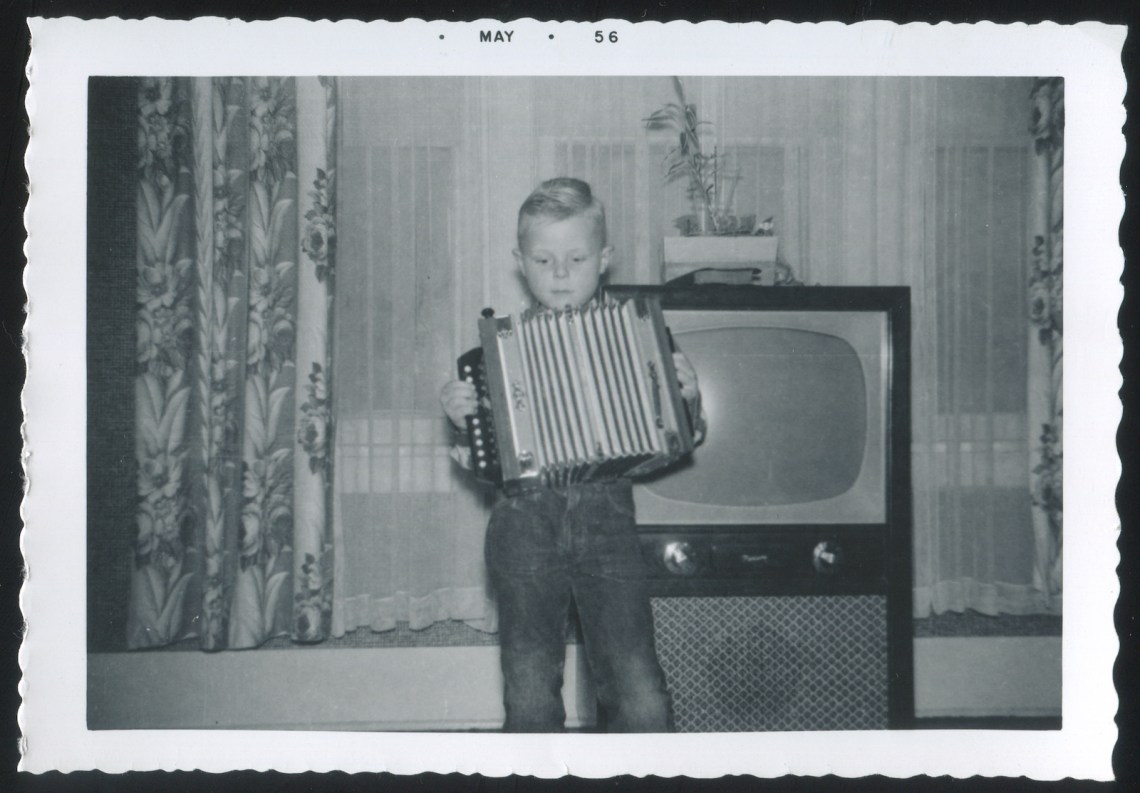

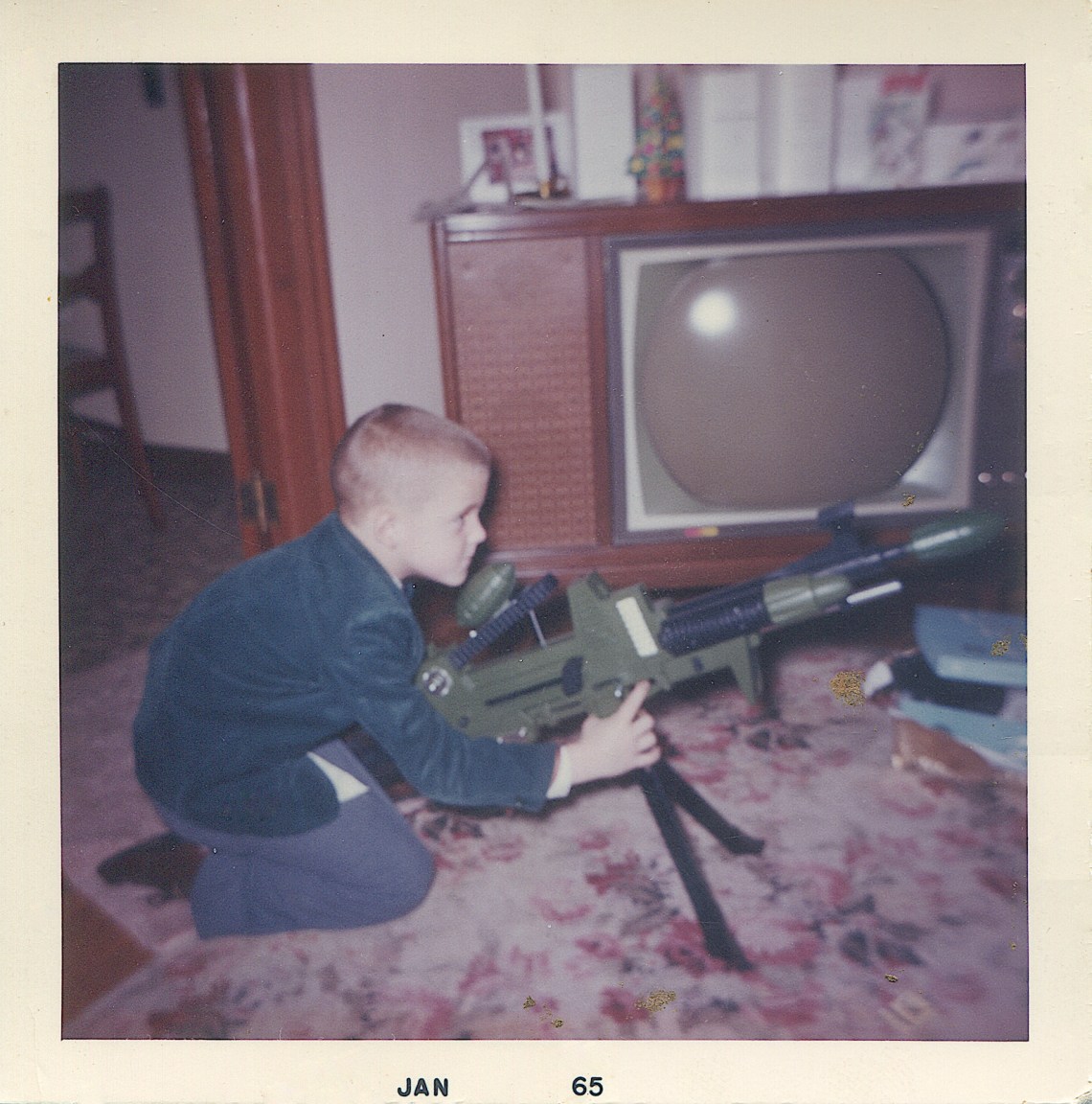

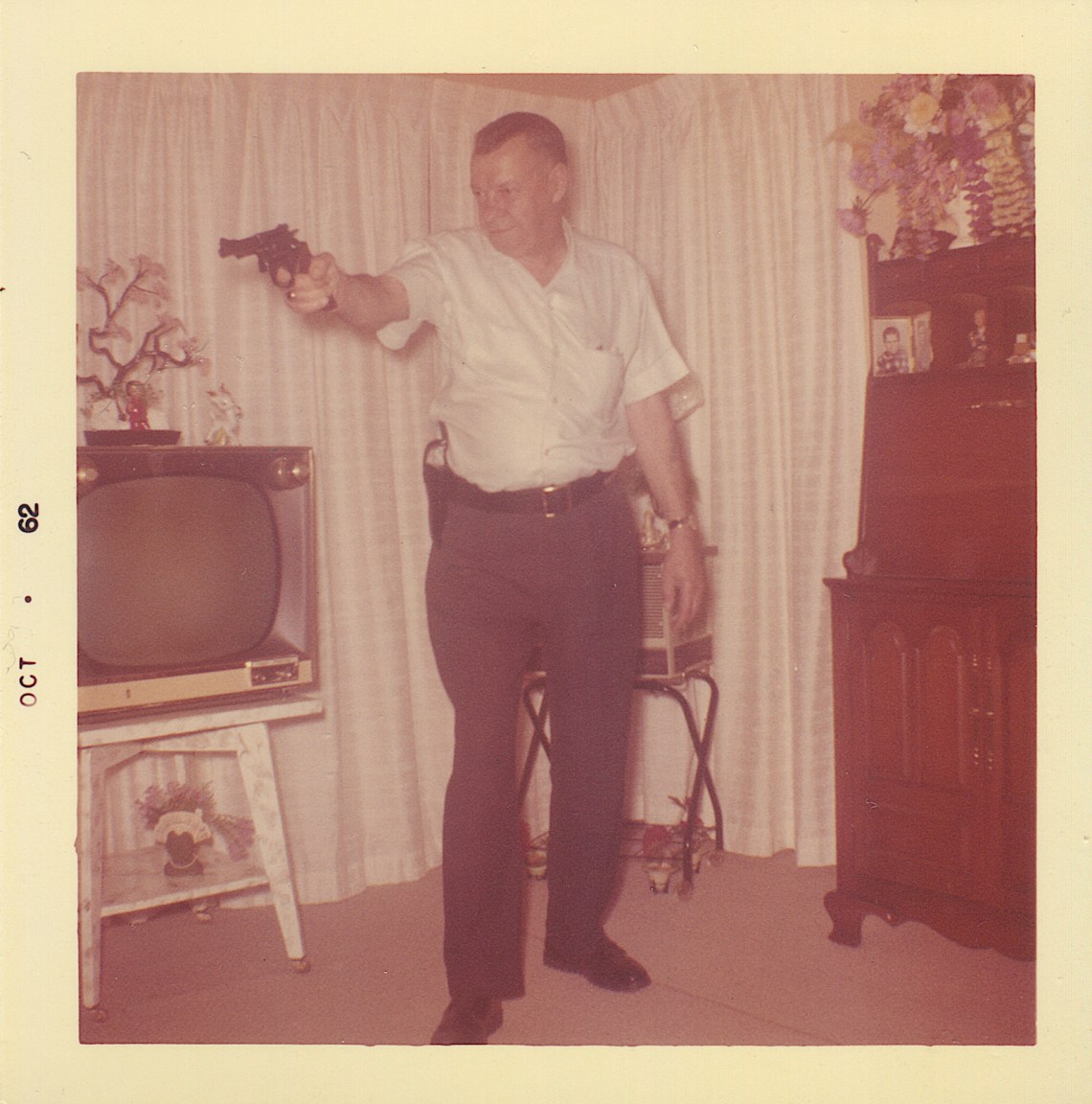

Spigel’s answer is to get to the punctum, that slippery wound of the image, from its obverse, the studium, Barthes’s term for “a kind of education (knowledge and civility, ‘politeness’)” formed by an encounter with multiple photographs in succession. To eschew the studium in favor of the punctum is to set oneself up for failure: slowly, in the uttering, the punctum will become its twin anyway. Spigel’s method moves in the opposite direction. She presents a rigorous study of one set of gestures in one setting: camera operators, most of them women, standing in front of their TV sets between the 1950s and the 1970s. On the face of it, this is pure study. But by opening up the American living room, she seeks to show us the slightly off, slightly wrong phenomenon of people gathered around the hearth of the television and its sanitized representations of families and experience. It turns out that posing for photographs with one’s television was a surprisingly common practice in this period, not unlike taking photographs in front of homes or new cars. The TV sat in the semipublic space of the living room, a threshold that invited play across the inner domestic and the outer social world.

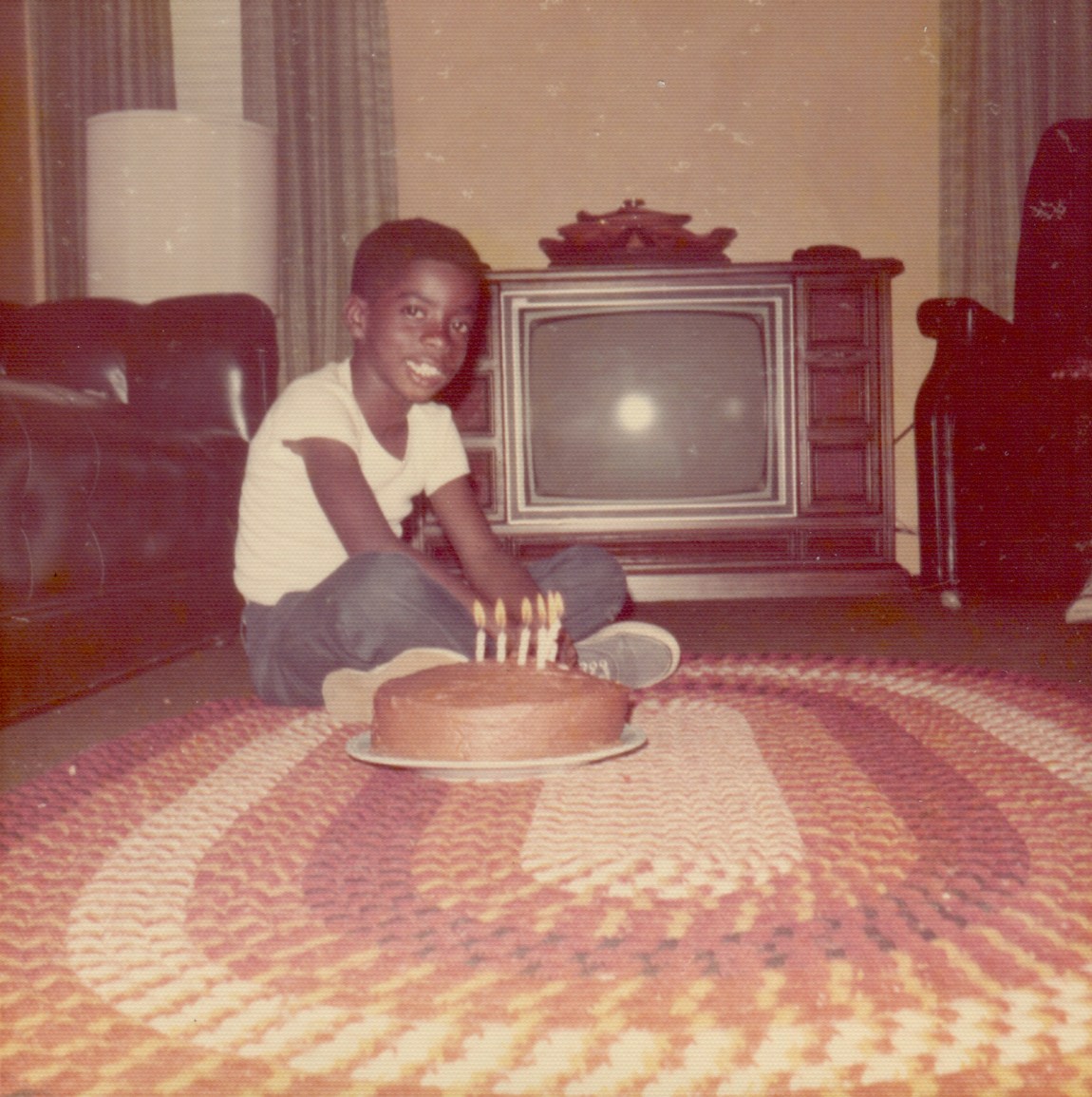

From an archive five thousand images deep, sourced from garage sales and eBay, received as gifts, and mined from her own family albums, Spigel presents 165 provocative examples of the TV snapshot. By curating this studium, she is really after the “low punctum.” Rather than a specific emotional wound or prick, as Barthes describes it (an oversized collar, a little bandage), she wants to catch the messy truth in its banality as it moves across the collection, only momentarily housed in the details of an individual photo: from the rat’s nest of power cables to the ill-fitting bathing suit of the person in front of the TV. Using the sum of these impressions, Spigel constructs a history and theory of what happened near the television in the “theater of everyday life.”

*

Spigel has, for the last thirty years, ingeniously documented television’s rise as the dominant medium in American life, pulling together an archive that demonstrates the flattening, normalizing effect of TV on the American family. Part of her work has been to scour sources that tell us what happened to, as she puts it, “make way” for television and to inaugurate a new era of intimate screen-human relations. Endless women’s magazines, advertisements, and television scripts glorified the television’s space in the home and its contribution to domestic peace, and families reorganized their lives around this domestic medium’s rhythms. TV Snapshots is Spigel’s fourth book to describe what people were doing with the television beyond, as we might assume, passively watching it.

Advertisement

In TV Snapshots, Spigel asks, following the Black feminist theorist and media studies scholar Tina Campt, that we “listen to images.” Only when we treat family portraits not in isolation (as “orphans”) but as part of a set, Campt argues, will they collectively tell us their historical and affective meaning. Each chapter of Spigel’s book concentrates on a subgenre of the snapshot, from glamour shots and drag to pinups. The result is a media history not only of the television and of photographic processes aided by the Kodak Girl (and, in Spigel’s words, “her Polaroid sister”) but also of how photography and television became “companion technologies,” both to each other and to us. Through the photograph, we were able to double ourselves, long before the camera phone and selfie. By doubling ourselves, we overwrote and talked back to life as television represented it. Home theaters, for Spigel, hosted two shows at once: the drama on-screen and the performance happening in front of it.

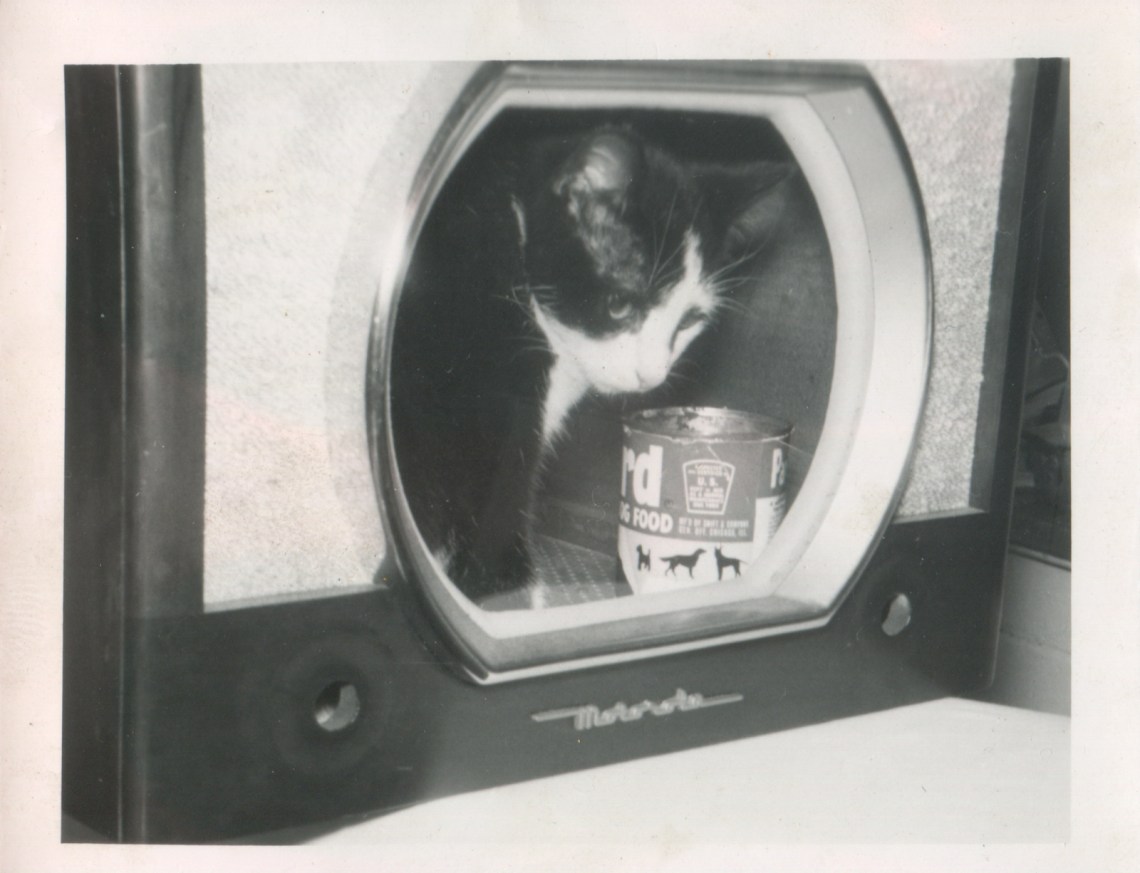

This is perhaps best illustrated when the TV is emptied of its actual function—transmitting programs into the home. By removing the screen, the creators of some of this book’s most delightful images turned the console into a frame for new forms of play. Spigel calls this the “trick shot.” Babies appear to be floating in the box on a screen that isn’t there; a woman sits inside her TV cabinet and poses as if in a commercial—becoming a product for sale; another sits next to her TV set, where her portrait is being magically showcased. Spigel traces this genre of image back to Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin’s mid-nineteenth-century Soirées Fantastiques and optical illusions, which eventually gave way to trick films. At midcentury, the TV was understood to be enchanted: a “magic mirror,” uncanny. By opening up the TV and reconfiguring it, these photographers commented on television as a black box, on the level both of its technological mechanics (how the thing works) and of who controlled the media (what messages it sent).

Relatedly, the television was understood to enchant and enthrall its audience. The TV watcher was subjected to many moral panics about media effects: addiction, bodily harm, the destruction of marriage, and social decay were all attributed to the boob tube. In TV Snapshots, Spigel is not particularly interested in discussing these panics, nor the oft-repeated question, familiar to those of us who lived through discussions about the “selfie generation”: Are we narcissists for photographing ourselves? Nor does she read the archive of TV snapshots as evidence for spectacular consumerism, which to her is “a rather unsatisfying explanation” for the ubiquity of documenting the home appliance. “It is not wrong, but it is weak.” Instead, Spigel recovers what she calls a “game of telepresence” between people and their screens. When Americans watched TV at midcentury, she emphasizes, they weren’t the pacified zombies that pediatricians and media theorists alike told them they were. Rather, they played along with television’s broadcasts and played against its ideological functions.

For instance, viewers turned the space in front of the television into a theater of sexuality. Every other major mass medium has been a site for pornography—amateurs took to the radio, and phone phreaks hacked the switchboards of the telephone—but early television, by and large, was impervious to such playful intervention because it was disseminated from government-licensed broadcast stations and tightly controlled. And yet the TV itself became sexy. “Rather than on TV,” Spigel writes in her chapter on the TV pinup, “in the early decades of commercial television, sex took place around it.” Women especially used the TV as a screen in front of which to get undressed as much as dressed up.

Spigel shows us how the snapshot camera and television kept company with other media: instruction manuals, men’s magazines, postcards, pinups. This proliferating printed matter found its way into the mainstream American home, where the professional photograph mixed with its amateur mirror image, the home snapshot. The images Spigel includes in her chapter on the pinup therefore range from the genre’s spectacular pioneers (Bettie Page, Bunny Yeager) to its sweet and quotidian practitioners (women seated or standing, posing as if proud, but not quite). Elsewhere in the book, the category is also expanded to include a litany of rare queer erotica, including images of men and women dressed in drag in their own living rooms, with the television as erotic furniture somewhere off in the background.

Advertisement

As in a photograph of a nude man using a TV Guide as a fig leaf, or a double portrait of pinup models posing in the wreckage of a TV repair shop, the mere suggestion of television suffices as prop. Television, in Spigel’s account of these images, is both a provocative, repressive site of spectacle and a piece of domestic architecture that supports performances of sexuality precisely because it lies in a collective space: the living room rather than the bedroom. Viewers couldn’t interfere in what was broadcast, but neither could the broadcast control what happened in the home.

Nowhere is the power of overwriting the hegemonic image of television more powerfully articulated than in Spigel’s work on the redress and readdress of the medium by Black families in their snapshots. Television in the 1950s and 1960s combined violent, stereotypical depictions of Blackness with staid, white images of America as it never quite was. In Spigel’s account, the TV snapshot gave Black middle-class families “ways to reappropriate” these “racist practices in mainstream visual culture.” She connects an archive of Black women’s glamour shots from the early 1970s to the civil rights movement: posing in front of the TV in sky-high silver lamé boots, jumpsuits, or hotpants was, she writes, a kind of “everyday glamour labor.”

These same TV snapshots of everyday glamour could also be turned to other political ends. Spigel’s archive of television history includes, she tells us, the photograph of Emmett Till posing in front of his family’s television that Mamie Till pinned inside her son’s coffin. (The image has circulated again once more in conjunction with the recent recovery of the 1955 arrest warrant for Carolyn Bryant Donham, the woman—still living—who accused Till of whistling at her.) Spigel doesn’t reproduce the snapshot in her book out of respect for “Mamie Till’s original purpose,” and she admits that to take it for TV history is to risk what Saidiya Hartman calls a “second order of violence” by inserting it into another archive, but she nonetheless argues that this image in particular was part of “Mamie Till’s desire to bring the photos of her son to public attention through mass media.” The paradox of not reproducing the image out of respect while claiming it in thick description is left unnegotiated. It has the effect of showing the many circumstances, uses, and deployments of TV images—here, to radically humanize a boy in memorial, after murder. Spigel suggests, in effect, that she needs to “listen to images” despite the risks of secondary violence, both to show that the TV snapshot’s “racial innocence” was far from total and to avoid implying that the genre only conveyed new understandings of white self-fashioning.

*

I began where Spigel ends: with our computational present, our modes of remembering and forgetting and the machines that mediate them. Spigel notes that although the cultural practice of taking TV snapshots continued after the 1970s, the snapshot camera and analog television died a twin death about ten years into this century. In 1910 advertisements told women to “Make Kodak your family historian.” Now the iPhone might well be. Preserving continuity across these radical shifts is, of course, nostalgia. Platforms for taking and posting selfies have long traded on remediating older photographic techniques and technologies, converting their limitations into filters.

TV Snapshots too offers us a way to rethink our own obsession with obsolescence. The longer arcs of our digital genres are everywhere in the book: TV snapshot as screenshot, TV snapshot as proto-selfie. At the end, Spigel turns to the afterlives of these images as kitsch for sale. Her curation mirrors the digital bookmarking and tagging of Pinterest and the traffick in nostalgia on eBay that Tamara Kneese and Michael Palm call “listing labor in the digital vintage economy.” In Spigel’s discussion of album-making, she considers how users of Flickr and other photo-sharing apps combine historical memory and self-curation to rewind and replay the past.

Of course, the reader of TV Snapshots has just witnessed this process unfolding. Starting with the first picture—Spigel’s own childhood TV snapshot—our encounter with the book’s images has been guided by a practice of selection, curation, salvaging, and restoration that remains implicit until the book’s conclusion. This is the low punctum I was entranced with, even as the decisions that brought out these particular 165 examples are obscured. In this respect, TV Snapshots is as much about what Diana Kamin calls “picture work”—the sorting and tagging of image collections performed here by Spigel, archivists, and sellers—as it is about the self-fashioning of these photographers, depicting daily life against the grain of its picture-ready representations. That self-fashioning operates in parallel with the historian’s curation. They are now each other’s conditions of possibility, thanks to Spigel’s efforts: building the set from eBay and dustbins, lifting the pictures from family albums, and turning them into a composite work of a generation. Spigel has yet again shown herself to be a signal historian of the family, helping us make sense of the ways we actually were, in the flickering light of the pressure to be otherwise.