And hand in hand, on the edge of the sand,

They danced by the light of the moon.

The shifting margin of sea and land, often lit by the moon, held a lure for Edward Lear, a tidal ambivalence. In 1836, when he was twenty-four and about to leave England to become a landscape painter, he stayed with friends near Plymouth. They sailed and swam and played their guitars on the rocks, “& there we sate singing to the sea & the moon till late.” It was one of many farewells to the sea.

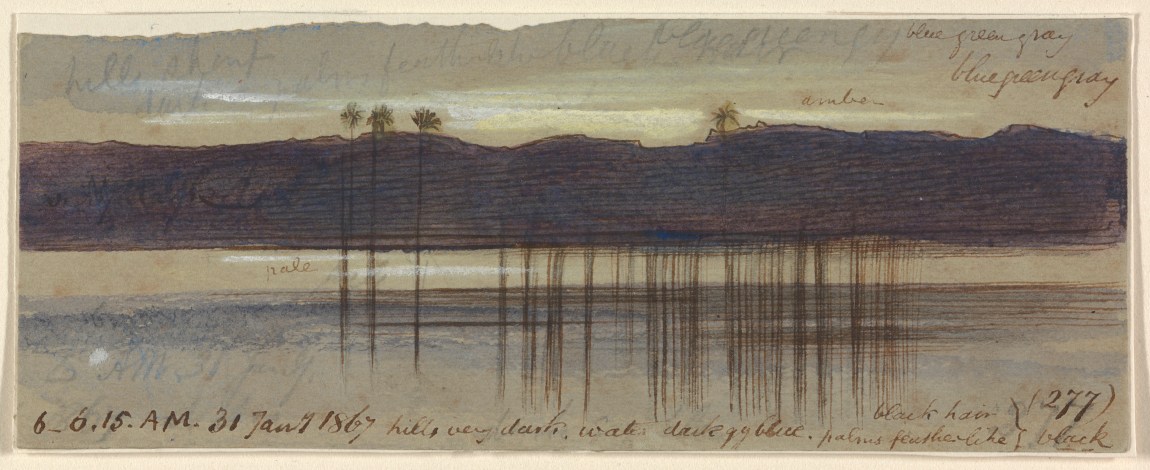

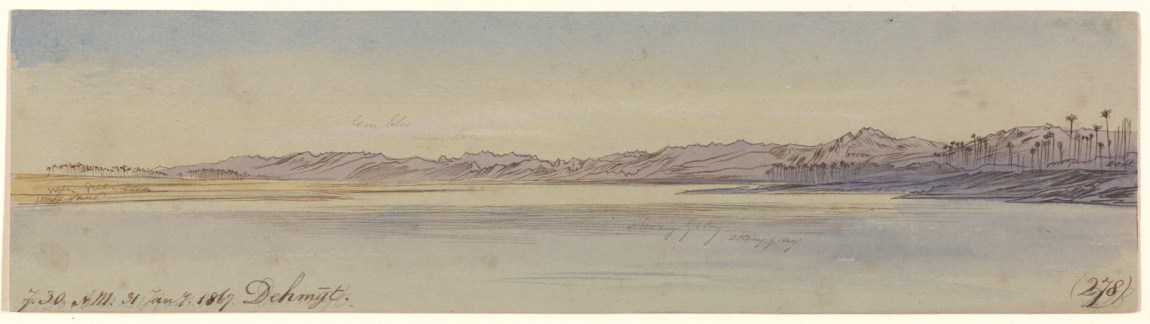

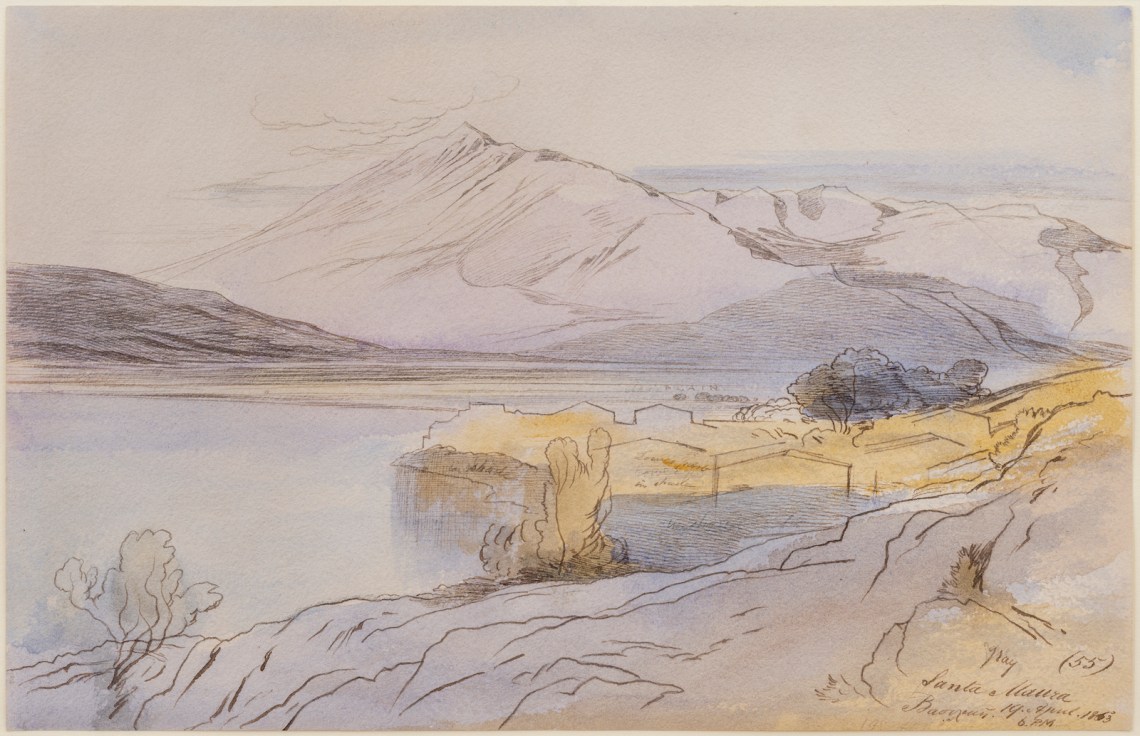

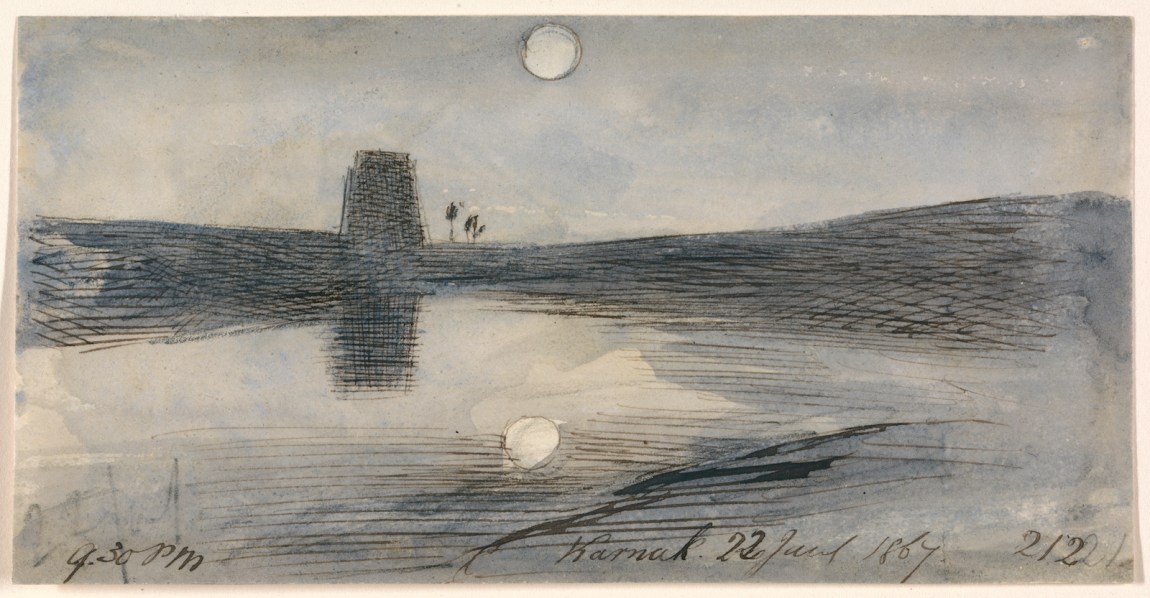

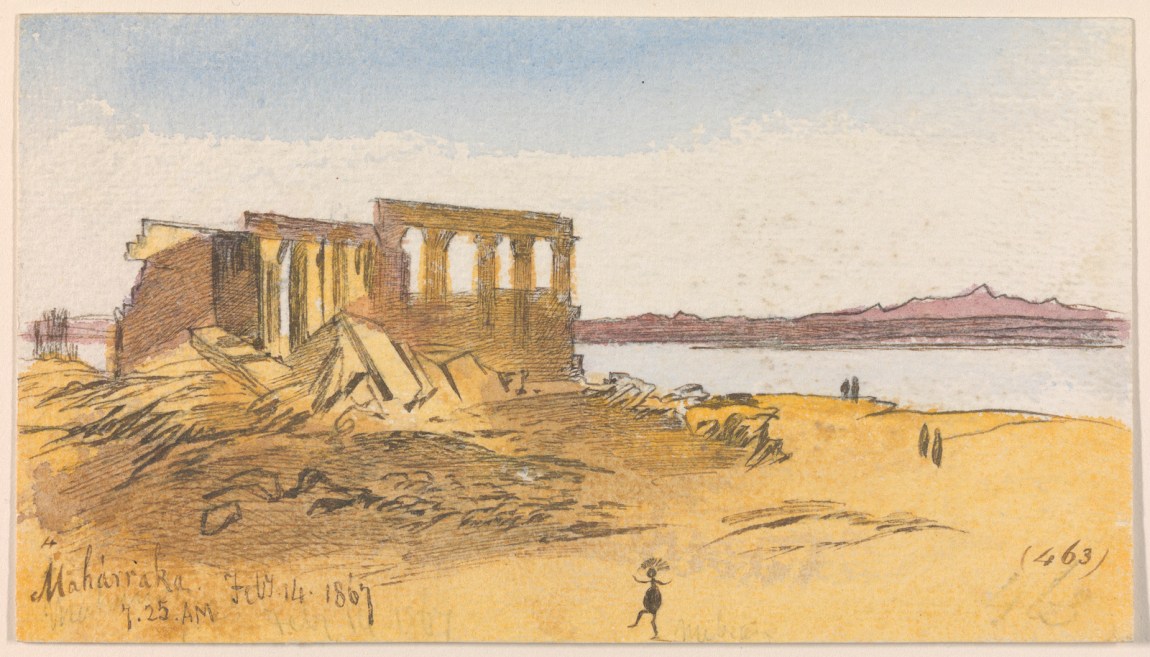

Lear’s travels took him to Italy and Greece and Albania, to Palestine and Egypt and India, to deserts and ruins and the banks of the Nile. Everywhere he went he carried his sketchbook, numbering drawings in sequence and annotating them with dates and times and quirky notes: “oker” for ochre, “rox” for rocks, “sno,” “blubels.” His countless sketches were the bases for lithographs, watercolors, and oils, but they were also an outsourcing of memory, a visual recording of life.

In his many coastal sketches, ports fling their arms around harbors, hill towns tumble to the shore, monasteries cling like limpets above thundering surf. These are safe havens, gazing at the ocean, but there is often a threat beneath the still reflections, a swell below the calm. Lear did not like sea voyages. He hated the fuss at customs, the packed decks, the vomit and wailing of the sea-sick, the dread of wreck. One winter, sailing from Marseilles to Civitavecchia, he braced himself to leave “the infernal Hole-cabin”:

so I did & went up on deck. The waves are really a wonderful sight! – deep blue-black, with silver crests – valley-making, gulfing – vast, forcible, opal-vitriol hued above, solemn inky below, – gull-abounding – ever-moving – terrible. But I lay & held on – as the vessel swooped & circled.

But the gale passed:

& then came the golden sunset, calm, & with one long purple, orange-lighted cloud above, & many a golden flecked streak at the water edge – the sun going down one full orb of sublimity: above the delicate new moon, & one star.

Setting sun and rising moon haunted him. In July 1847, exploring Calabria, he sketched the great rock of Pentedattillo (“Pentedattilo,” as Lear writes it) looming like a giant hand against the sky. Later he reworked this in a rosy wash, adding no date.

This view became a recurring motif, used several times in his later life as an image for lines from Tennyson’s “The Palace of Art,” slightly misquoted:

One seemed all dark & red a tract of sand

With some one pacing there alone

Who paced for ever in a glimm’ring land

Lit by a large low moon.

A similar lonely regret rings through another repeated line: “We come no more to the golden shore where we danced in days of old.” One such shore was on Corfu, where Lear hoped, in vain, to live with his young friend Franklin Lushington, who was appointed a judge in the Ionian Islands in 1858. Here he bravely went sailing in Lushington’s boat (“roll, roll, pitch, pitch, creaking, flapping and bumping till I could have thrown myself overboard”), landing in bays, including his favorite, Palaiokastritza, that were like an embrace.

In other Corfu scenes, he looked down from heights, away from the shore, across the straits to the Albanian mountains. In these views mountains float above the water, evoking an unreachable beyond, like the dreaming shapes in the lovely outlines of Aegina, drawn on his visit to Greece with Lushington in the spring of 1849.

Lear made Corfu his base until 1864, when the Ionian Islands were returned to Greece. After he left, he spent a month on Crete. On Sunday May 8 he rose early, “the world very clear & blue. Then we came down to the sea, which is perfectly calm, & like a large opal mirror—& sat on the sand until 9:30.” The next day, on the old steamship Persia, he made a string of watercolor sketches: of Mount Ida at 4 PM (“vast,” his note said), rising above gray-green slopes; again at 5:30 from a different angle, with snowy heights catching the light and a rocky outcrop breaking into the pearly sea (“wild, grand coast,” he noted).

More sketches followed fast: Mount Juktas, a hazy purple bulk above a rough wash of blue, and Ida again at 6:30, receding into the distance, “lost behind the great northern bluff coast cliffs.” He could not hold that vision, lost behind the bluff, but his sketches preserved it: caught in a moment, instantly past. When he sailed at the end of the month, aboard the Persia again, he drew Mount Ida against a tawny sky at 8 AM, “pale as a cloud.” As they sailed, he wrote in his diary, “all Crete diminishes – fades & vanishes…” Last of all, “Lo! Ida fades.”

Advertisement

The Cretan sequence lets us see Lear turning his back on the hubbub on deck, looking, drawing, wetting his paintbrush, working from minute to minute. But at the end of the year, that lyrical Learical coast, sketched from the sea, was balanced by a tougher shoreline, drawn from the land. That winter, with his Corfiote servant Giorgio Kokali, Lear stomped from his rooms in Nice along the coast, through Menton and Monaco and Alassio, all the way to Genoa. It was icy cold, with perpetual rain and wind, and far from peaceful, with the building of a new train line. “I tire sadly of this Cornice,” he wrote, “the lopsided views & blank gray sea – & this everlasting smash of railway cuttings & blowings up & knocking down.” “Ever the growing railway aboundeth,” he groaned. Yet he drew constantly—a series of fast, almost abstract sketches, strong and wild and unconventional. Surf breaking on the rocks at Finale, or a ghostly Oneglia seen through skeletal trees. (“Rain,” he writes glumly.)

In the drawings of the mid-1860s nonsense scribbles and wayward details sometimes creep in, such as the penguin-like figures in their headdresses and the exclamation “O dantesque female!” on a sketch made in Corsica, opposite Calvi. Lear’s “lopsided views” resemble the restless poems and songs he wrote during these years. Strange things happen at sea, defying the logic of land, even on a short crossing of the Bristol Channel, where the Pobble is so strangely toeless when he swims ashore, and nobody knows “Whether the shrimps or crawfish gray, / Or crafty Mermaids stole them away.” The ocean changes his nonsense beings, sweeping them in and out, pushed and pulled by tides of longing. Thus the Dong with the luminous nose scans the horizon for the Jumbly girl, who came from the sea, and played and danced

Till the morning came of that fateful day

When the Jumblies sailed in their sieve away,

And the Dong was left on the cruel shore

Gazing – gazing for evermore, –

Ever keeping his weary eyes on

That pea-green sail on the far horizon.

But while the Dong is landbound, the Yonghy-Bongy-Bò, his proposal declined, offers a reverse image. Leaving Lady Jingly weeping on her heap of stones he flees on the turtle’s back, through “the silent-roaring ocean” to that distant far horizon, “With a sad primeval motion / Towards the Sunset Isles of Boshen.” In the western seas—like Lear’s floating mountains—lie the Hesperides, the Sunset Isles, the immortal lands of “bosh.”

Lear’s edgily brilliant nonsense people and creatures morph easily into other forms—noses extend, arms spread like wings. Lear himself often seems to be a liminal creature, broaching boundaries and absolutes of society, gender, bodies, and language. In letters his rotund caricature flies like a bird, or swims with the geese “all the way round cape Matapan & so to the Piraeus as fast as we can.”

In his limericks, too, people are often half in and half out of water, as if unsure in which element they belong. While they long to sail, they also long to stay. There’s the Young Lady of Portugal, “whose ideas were exceedingly nautical,” and who “climbed up a tree, to examine the sea / But declared she would never leave Portugal.” That seems definite enough, but in one manuscript version, as Matthew Bevis has pointed out, the converse is true: the Young Lady tilts firmly seaward and the last lines run “She felt deep emotion, on viewing the Ocean, / & sighed to be gone out of Portugal.”

And what are we to make of this disconsolate limerick, which was included, with the Portuguese drama, among the new verses in A Book of Nonsense in 1861?

There was an Old Man in a boat,

Who said, “I’m afloat! I’m afloat!”

When they said, “No you ain’t!” he was ready to faint,

That unhappy old Man in a boat.

His boat seems both in the water and on the land. Is he faint because he wants to go, or because he fears he will? Has he fallen by accident into the boat? Is he throwing up his arms in delight—“Look at me floating!”—or in despair? Is he always “unhappy,” or just now? Are the onlookers on land, or in air? We are suspended in uncertainty.

In some of Lear’s most evocative sketches, uncertainty takes over almost completely. The boundaries of earth and sea dissolve. In a foggy Venice, in November 1865, he used pale washes of blue and gray, with amber tints and dark reflections, so that city and lagoon become one. From Venice he went to Malta, and here, in a sketch of Sliema in March 1866, the solid shore disintegrates. We are left with a rippling edge and a halo of mist around a pale setting sun—or a rising moon (it is hard to tell the time of day without Lear’s usual note). Hovering between conflicting states, he dances on the edge of the sand.

Advertisement