“Day one post balloons.”

That is how Joan inscribed her book After Henry, which she gave me the day after the balloons dropped and the Democrats finished their 1992 convention. Those four words, for me, captured Joan and the moment itself: the superficial excitement of the convention, the silly balloons dropping, but also a beginning. The first day of something more promising, more real.

I first met Joan and John at their Malibu house in the Seventies, but I didn’t get to know her until she invited me to stay at her apartment for those days when I was in New York City during my presidential campaign. I had made it a practice in that campaign to avoid hotels and stay in the homes of friends and supporters.

I heard about Joan from my sister Barbara, who got to know her at the Tri Delta sorority at Berkeley in 1953. My sister majored in English, like Joan, and wrote for The Daily Cal. She and Joan would share a smoke together and talk about the novels they were reading. Years later, my sister still has a vivid memory of Joan coming down for breakfast in a pink chenille robe, drinking a cup of coffee and smoking cigarettes.

Joan said that she was influenced by Mark Schorer, a legendary professor at Berkeley. So was my sister. That made me think of my own experience in Professor Schorer’s literature class. On the last day, as he finished his lecture, he took a long drag on his cigarette, exhaled slowly and intoned, “this class ends on the downbeat. That is just the way it is.” He turned and walked slowly off the raised platform in Dwinelle Hall and out the door.

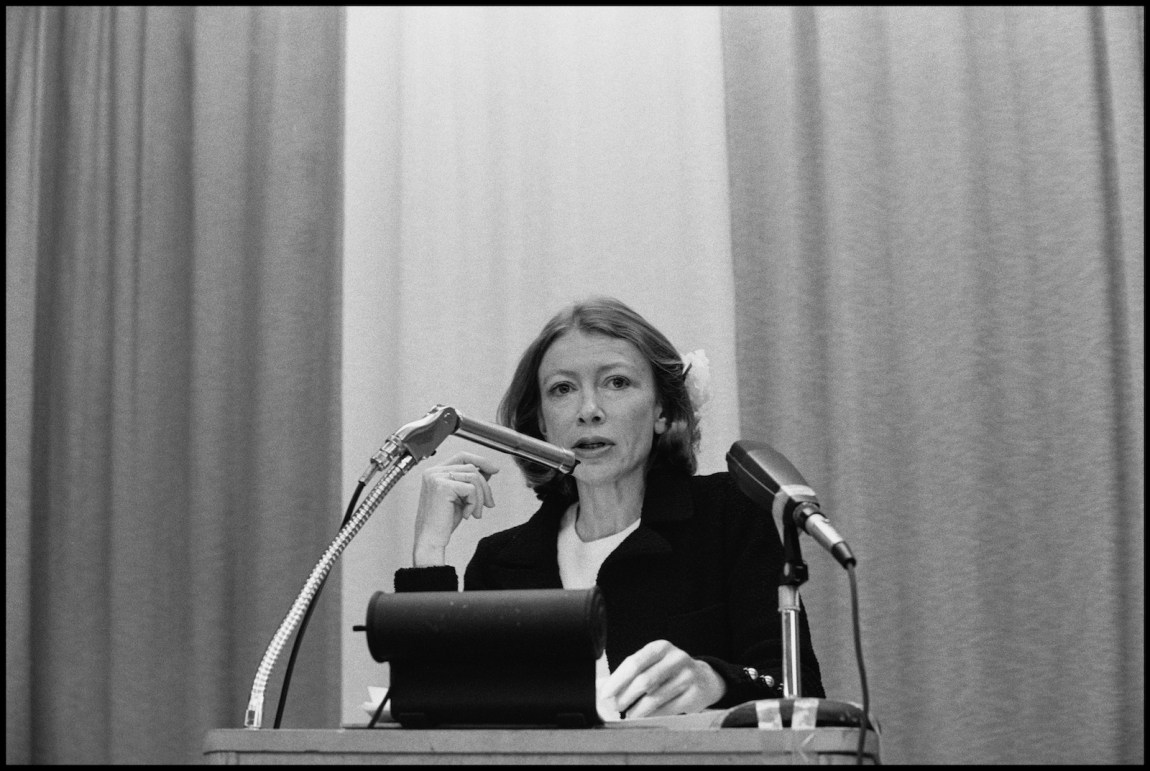

That stark view struck me as revelatory, as an authoritative statement of the age, as the new dispensation that would now replace the one I had left behind at the Sacred Heart Novitiate the year before. Because it has stayed with me all these years, I wondered if similar sentiments also touched Joan and influenced her understanding of what she called “the whole grand pattern of human endeavor.” “We all stand,” she told the graduates at UC Riverside in 1975, “on the brink of something every day we get out of bed, and it usually turns out to be a precipice.”

In that same commencement address, she spoke so frankly about her own life:

I’ve had to struggle all my life against my own misapprehensions, my own false ideas, my own distorted perceptions. I’ve had to work very hard, make myself unhappy, give up ideas that made me comfortable, trying to apprehend social reality. I’ve spent my entire adult life, it seems to me, in a state of profound culture shock.

That year, following eight years of Ronald Reagan, I moved to Sacramento for my own time as governor of California. And I chose to live in an apartment rather than the new governor’s mansion that Nancy Reagan had built. Nancy said the old mansion that had housed every governor since 1903 was now a fire trap and no longer suitable. Actually that was not true—it was a perfectly fine house, the most splendid Victorian mansion in all of Sacramento. Joan spent some time there as a young girl when Earl Warren was governor. (His daughter Nina was a year ahead of her at McClatchy High School.) Joan said the old governor’s mansion was “my favorite house in the world.” I spent many happy hours there when my father was governor and later lived in it during the last years of my own governorship.

Yet it was the new mansion that really caught Joan’s attention. In her famous essay, “Many Mansions,” she said it was “a house built for a family of snackers.” It was “a case study in the architecture of limited possibilities…and as devoid of privacy or personal eccentricity as the lobby area in a Ramada Inn.” She wrote, “It is the kind of house in which one does not live.”

Joan ended her essay with these haunting words: “I have seldom seen a house so evocative of the unspeakable.”

From her own sense of her forebears, from that earlier time in California of straight-talking, hard-living pioneers, Joan crafted her own unique sensibility of distance and biting clarity. She was gentle in person, and quiet-spoken, but ferocious in her honesty.

Going back to Riverside, her words that day could stand now as fitting epitaph: “I’m talking about trying not to be crippled by ideas. I’m talking about looking out, about looking out at the world and trying to see it straight, about making that effort to look out for the whole rest of your life.” Joan Didion was a Californian all right. She was gentle and she was fierce. Sadly, very sadly, we won’t be seeing the likes of her again—ever.

Advertisement