It must have been in the spring of 2018, because that was the last time I was in Paris. I had been invited to give a talk; my hotel was near the Church of Saint-Sulpice, which I had never visited before. And in that immense cathedral my heart began to pound, because walking beneath those vaulted ceilings, and past the candles, and still-life scenes of mortification, and other citizens waiting to take communion in what felt like the most public way possible, I felt what I was meant to feel in that eighteenth-century edifice: the smallness of man, and the large invincibility of God.

It was like walking onto a gothic soundstage, those moments I spent at Saint-Sulpice, but I couldn’t place the movie; in any case, the gothic there belonged to Orson Welles and not to that city’s premier filmmaker about cities, Jean-Luc Godard. It was sort of interesting, for a time, to imagine what Godard would have made with the space; he’d already made much of Catholicism, and the Gallic mind, in Hail Mary (1986), yet another one of the master’s takes on a canonical text—cinema as a form of rewriting, just as performance is a kind of rewriting of the primary text.

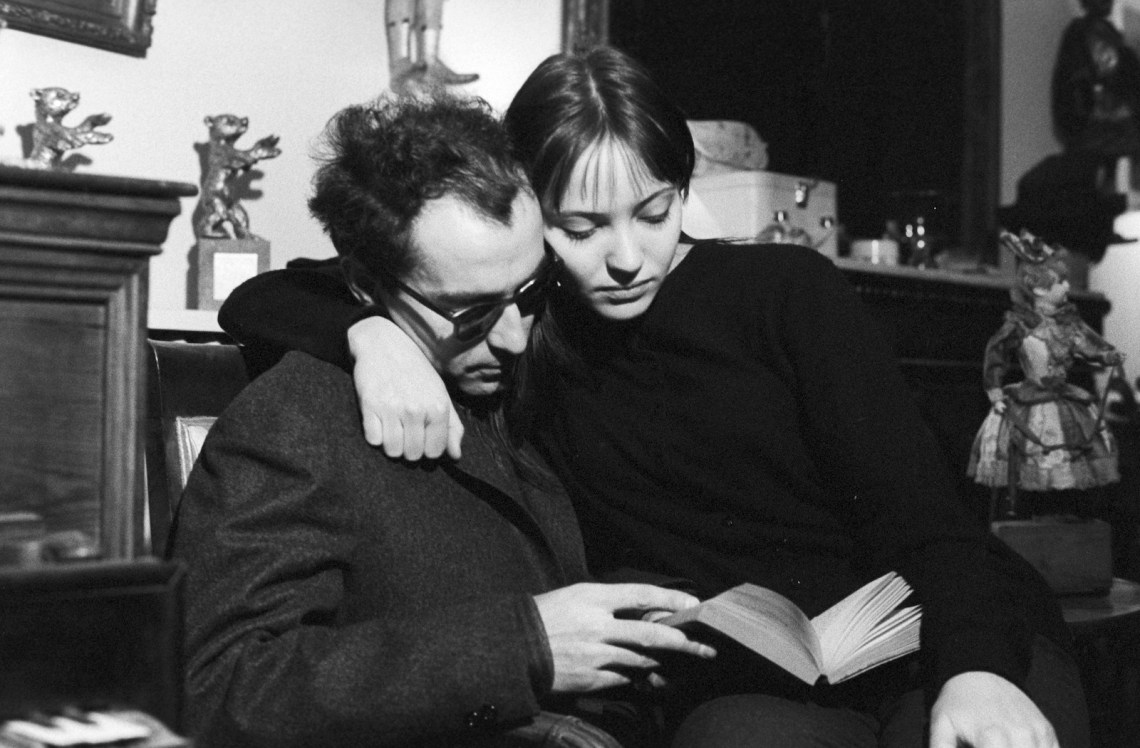

To my knowledge, Godard, who died last week at ninety-one, never shot in Saint-Sulpice, but of course he had the stars of his wonderful Bande à part (1964) run through the Louvre to kill a little time, even as time was killing them. Starring three young performers at the height of their beauty and ability to fascinate—Anna Karina, Sami Frey, and Claude Brasseur—this film, Godard’s seventh full-length movie, is, ostensibly, an homage to gangster flicks, but to me it’s about how youth doesn’t know itself, and what that confusion of energy and intention looks like as it plays out against history—in grand edifices like the Louvre. Indeed, the city itself was, for many years before he moved to Grenoble in 1974 and then to Switzerland in 1977, a kind of muse to the director, and he photographed its “dead” parts—its museums and libraries and river—along with its “new” ones, including its cafés littered with pinball machines, jukeboxes, noise.

When I recall Godard’s early work, I think about his use of sound as much as anything else, including all those car horns and cash registers that are not only the sounds of modern life but become, in Godard’s hands, extra characters in his movies from the mid-to-late Sixties on. Think of that extraordinary tracking shot in the supermarket in the underrated Tout va bien (1972). Oranges, coffee, oats, paper towels, meat, are checked out and purchased at a rapid rate while Jane Fonda, brilliantly cast as an American reporter named Suzanne, walks back and forth, observing commerce at work. Early in her career, certainly, Fonda had been used, to some extent, as a commodity herself, and in Tout va bien, she is both an American reporter and herself, or, more specifically, a self-discovery: Tout va bien was shot a few years after she turned her back on Jane Fonda, cinema object, to become Jane Fonda, serious performer and activist. Godard’s brilliant awareness is that in addition to watching a story we are watching his stars—whether it be Karina, Marina Vlady, Anne Wiazemsky, Fonda, or Paris—as their respective identities, their true selves, merge with the fiction we’ve made of them, the fiction gender and commerce have made of them.

In Godard’s early films, character is destiny, but in later masterworks such as King Lear (1987) character is text—someone saying their lines. Indeed, what is Godard’s King Lear but a series of utterances about Shakespeare, and the failure of the father to understand not only the daughter, but her young and tender world? If I close my eyes, I can still see and feel the thrill of watching Norman Mailer’s daughter, Kate Mailer, enter the frame, sit down, and start leafing through the pages of a manuscript, presumably by her father, the Literary Big Daddy of them all. There is such sensitivity on Godard’s part to a girl trying to decipher her father’s language; and is that language really him, or is the real him—Mailer, Lear, all those old men—not “just” in the pages of a book, but in the body that has helped make her own?

King Lear is Godard’s comment on his own mortality as well; before, he left it to actors like Karina and Belmondo to talk about their time, to express the boundaries and freedoms of youth while he stood back from the proceedings, but in Lear he was sizing himself up, especially when it came to women, who have always been the intellectual and emotional frame for his movies. Of course, Paris was the “elle” just as much as Vlady, the star of Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967), was. That film is filled with whispers—Godard off-camera talking softly to us about Vlady, a woman who is both a character and herself—and gossip about the changing face of Paris.

Advertisement

Like Atget’s before him, Godard’s images can seem, at first, “boring”—colorful but flat, a series of words that stand in for a human tableau—but that boredom is based on the director’s sense that narrative is a secret not worth keeping. Cinema is a gift in that it allows for exposition—the betrayal of secrets—in frame after frame, actress by actress. Indeed, Godard’s women—from Karina to Isabelle Huppert to Hanna Schygulla and many more—have the singular honor, almost always, of knowing that cinema is a lie—if we want to believe in lies. The truth is much more remarkable, just as this person or that is much more remarkable than character.

But Godard knew that people need metaphors, too, and what’s more beautiful than Karina believing she is Nana, a sex worker, in Vivre sa vie (1962), even as Nana feels like Falconetti playing Joan of Arc, and then later wanting to be a philosopher? Words give us the power to say whoever we think we are, while the camera tells the audience who that person speaking the words really is. Nana lives in an ancient culture but is filled with new ideas about existence, about possibility, and how to undo what is done to her because she’s a woman. Unlike in the later films, where Huppert and others express the director’s mirthful cynicism, Karina was the wound at the heart of hope, and for the years he was with her—the couple was married from 1961 to 1964—Godard gave himself, and Karina fought for, the power of hope.

On my last day in Paris that winter’s afternoon, the same afternoon I went to Saint-Sulpice, I was walking by a café and I stopped short because there in her trademark fedora was Anna Karina having a little Pernod with her husband, the director Dennis Berry. She was doing all the Parisian things—smoking, drinking—and when I came to her table to pay my respects, Mlle. Karina said, “My husband is an American, too. Please sit down.” The hour or so I spent in her company showed me what Godard saw in her in the first place, and why they had needed each other: to give ideas to the body, and the body to ideas. Which is what cinema is all about.