Two weeks ago, the Supreme Court took a break from wrecking our rights to hear oral arguments in a case about a series of Andy Warhol silkscreen prints of Prince. It was an unusually raucous affair. Justice Kagan ribbed Justice Thomas when he confessed to liking Prince’s music in the 1980s. “No longer?” she asked. “Only on Thursday nights,” he replied. The courtroom erupted with laughter then and a dozen or so other times over the course of the morning. In a term full of proceedings that will imperil voting rights, affirmative action, and democratic elections, perhaps the Court felt it deserved some levity in a case about a pop star and an iconoclast. But the stakes are high here, too. Depending on who you ask, the case has the potential to diminish copyright protections or chill artistic progress.

The dispute arose in 2016 when a rock photographer named Lynn Goldsmith claimed that Warhol had infringed the copyright of a picture she’d taken of Prince when he used it to make several prints. In deciding the case, the Justices will have to clarify when artists can lawfully borrow from copyrighted artworks under a doctrine called fair use. Copyright law is meant to incentivize creators to make new things by giving them control over how their work is displayed and reproduced, and by limiting their ability to copy and profit from the works of others. Fair use carves out a defense for creators who build on existing works to make new ones. But drawing the line between borrowing and stealing turns out to be complicated. A federal statute provides four factors for assessing if a use of copyrighted work is fair: its purpose and character, the nature of the original, the amount that was borrowed, and the effect of that borrowing on the original’s market value. Courts have typically interpreted the first factor to measure how much the secondary work transformed the original, and found this decisive.

Artists who borrow, like Warhol, Jeff Koons, and Richard Prince, are frequently sued by the people they take from. But many of these lawsuits have ended in settlements, and the ones that made it to court have produced murky guidance. These decisions have forced judges, like philistines at an art opening, to weigh in where they may feel they don’t belong.

In 2006 the federal appeals court in New York decided a case about a Koons collage that placed magazine photographs of women’s legs against pictures of desserts and Niagara Falls. The photographer of one pair of legs had sued Koons. The judges, relying on the artist’s own testimony about his intent to convey a particular message, decided that the collage transformed the photo enough to count as fair use. They seemed relieved that Koons himself had supplied the analysis, since they felt that it was not their job to “judge the merits” of the work. “Although it seems clear enough to us that Koons’s use of a slick fashion photograph enables him to satirize life as it appears when seen through the prism of slick fashion photography,” the panel said, “we need not depend on our own poorly honed artistic sensibilities.”

The same court seemed more comfortable relying on those sensibilities in 2013, though, when they decided a case against Richard Prince, who uses appropriation the way painters before him used oils and brushes. The photographer Patrick Cariou accused Prince of stealing his pictures of Rastafarians to make a series called Canal Zone. The court found that twenty-five of the thirty works were transformative and protected by fair use. “Where Cariou’s serene and deliberately composed portraits and landscape photographs depict the natural beauty of Rastafarians and their surrounding environs,” the court explained, “Prince’s crude and jarring works, on the other hand, are hectic and provocative.” One judge dissented from this part of the decision, which he found unprincipled. “Certainly we are not merely to use our personal art views to make the new legal application to the facts of this case,” he wrote. “It would be extremely uncomfortable for me to do so in my appellate capacity, let alone my limited art experience.”

Since they come from a lower court, neither of these cases are binding on the Supreme Court Justices, but they tee up the issue that’s now before them. The highest court has decided cases about the fair use of copied computer code and parodic songs before, but never about how the doctrine applies to visual art. To determine whether Warhol transformed Goldsmith’s picture enough to merit fair use, the Justices will have to decide what kinds of transformation matter and whether judges are equipped to perceive them.

*

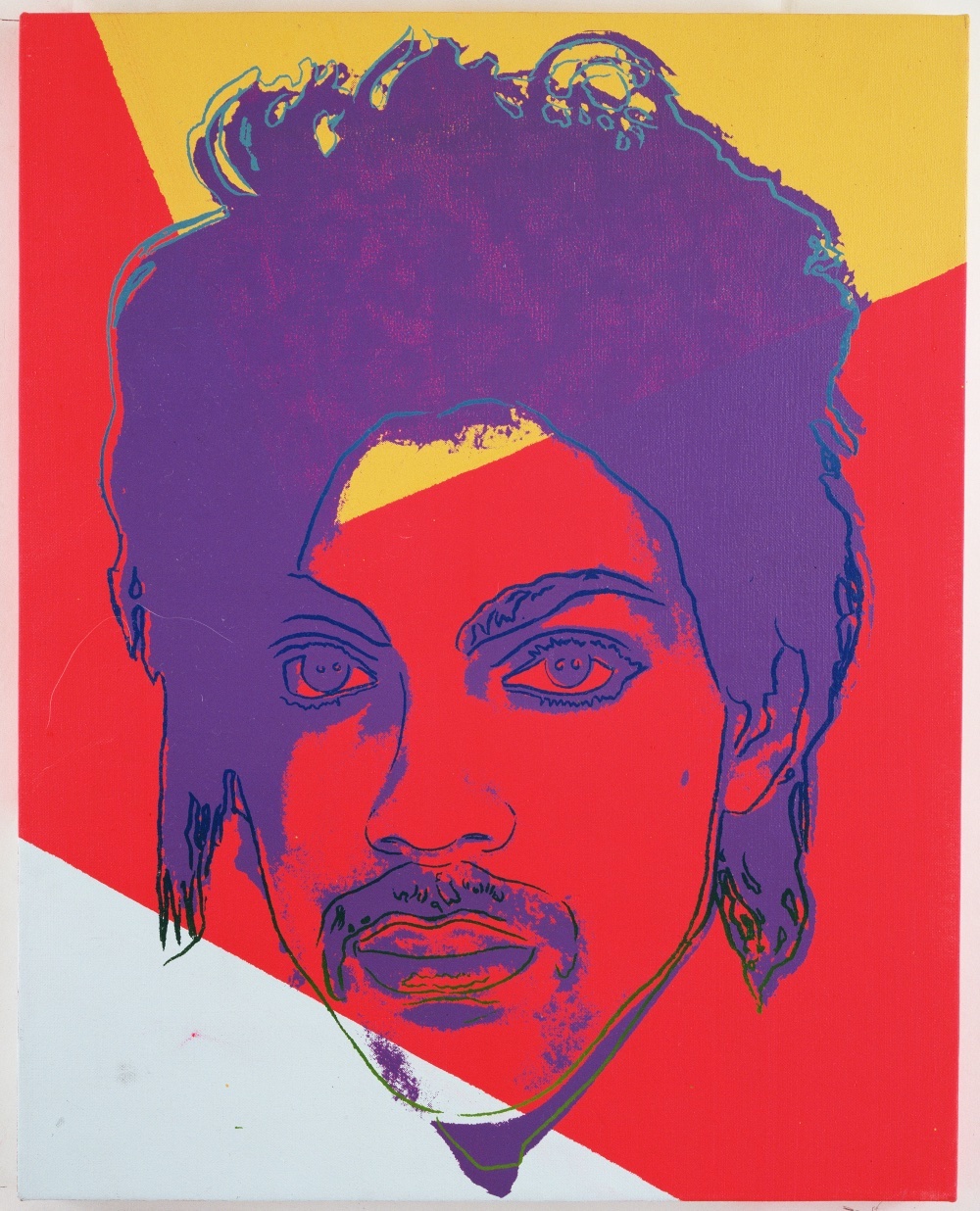

Goldsmith’s photograph captured Prince at a photo shoot in 1981, as his star was rising. He looks stiff and a little unhappy, his hands tucked in his pockets and his lips slightly pursed. Shortly after the picture was taken, he abruptly left the shoot. It’s easy to see the discomfort on his face once you know it was there. Warhol used the picture to create several prints that preserve the outline of the musician’s features but fill them in with brilliant colors—psychedelic pink, seafoam blue, perfect purple.

Advertisement

One of the prints, published in Vanity Fair in 1984, was properly licensed and gave attribution to Goldsmith, but the rest, including an orange print that ran as the cover of a Condé Nast commemorative issue in 2016, were not. After getting a letter from Goldsmith that accused Warhol of infringing her copyright, his foundation went to court to argue that the prints were protected under fair use. This was at least the fourth time Warhol had been accused of stealing, but three earlier cases—involving prints of flowers, race riots, and Jacqueline Kennedy—settled before a court could decide whether he was in the right. This time, the Andy Warhol Foundation led the charge, hoping to get a ruling in its favor and settle the matter once and for all. Soon after, Goldsmith countersued Warhol for copyright infringement.

The first judge to hear the case, in a federal district court in New York, concluded that what really mattered was that Warhol’s prints had a different meaning and message than Goldsmith’s photo. While Goldsmith showed Prince as a “vulnerable human being,” the court explained, Warhol depicted him as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.” “Moreover, each Prince Series is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince,” the district judge wrote. This qualified the prints for fair use.

On appeal, a panel of three judges took issue with the trial court’s interpretation of the two works. The problem was not that it had incorrectly analyzed their meaning, but the fact that it had done so at all. Whether a work is transformative, the panel reasoned, could not turn on the “impression that a critic—or for that matter, a judge—draws from” it. This was both because “judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.” The appeals court instead took what it seemed to think was a more neutral approach. It compared the surface of the works and found that Warhol could not benefit from fair use since the Goldsmith photograph remained the “recognizable foundation” of the Prince series, which preserved the “essential elements” of its source. The visual similarity between the two works could not be justified by the fact that Warhol’s meant something different. Unlike the Koons and Prince works that were entitled to the fair use defense, the court explained, Warhol’s prints had not “juxtaposed” a copyrighted photograph with other images. The implication seemed to be that, to avoid being sued, artists who want to borrow must collage.

The decision has set off the art world. By finding that new meaning isn’t enough to qualify works for the fair use defense, it endangers a great deal of contemporary art that relies on copying. Organizations representing Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg, documentary filmmakers, fan fiction enthusiasts, and the Brooklyn Museum, among many others, have written to the Supreme Court to try to sway its decision. “Far from lacking creativity, incorporating or appropriating existing source material—sometimes with little change in outward form—is in fact a wellspring of precisely the type of artistic expression that copyright law is intended to promote,” reasoned one brief signed by artists including Barbara Kruger, whose work frequently splashes words over borrowed pictures.

In her brief, Goldsmith has tried to present the case as a fight between David and Goliath, with Warhol as an artistic giant who turned a profit at the expense of humbler photographers. This framing is a little persuasive. When Condé Nast ran Warhol’s orange print of Prince in 2016, the Warhol Foundation was paid $10,250; Goldsmith got no money or credit. Around the time he created the series, Warhol was delegating the production of commissions so that he could make fifty pieces a year, charging $25,000 each. The foundation’s assets now amount to around $337 million.

But the stakes of this case cut in the opposite direction. The history of copyright law has been one of expanded protections for powerful copyright holders won by Goliaths like the Walt Disney Company. Goldsmith may be the little guy here, but a ruling for her would eviscerate a legal defense that has long protected underdogs from costly litigation.

*

Oral arguments last Wednesday left it unclear what the Court will do. Some of the Justices’ questions suggested that they thought the purpose of Warhol’s prints was commercial, which would cut against a finding of fair use. They seemed concerned, too, that ruling for Warhol could diminish what are known as “derivative rights,” which give copyright owners control over adaptations. If new meaning is enough to satisfy at least the first factor of fair use, the fear is that movie producers who want to adapt a book could just alter its message and not pay a dime.

Advertisement

But the case’s outcome will also rely on how the Justices view the meaning of art and their place in interpreting it. Warhol’s foundation has insisted that the artist’s prints convey a new message about the “dehumanizing nature of celebrity” and the “contemporary conditions of life.” Goldsmith, on the other hand, has argued that discerning what art means is “as reliable as divining animal shapes in cloud”—that meaning shifts over time, that different audiences will disagree, and that some artworks mean nothing on purpose. Her goal is to convince the Court that what art means should not be part of the legal standard. She wants the Justices to find instead that fair use only applies when an artist needs to use a copyrighted work to achieve some specific end, the way a parody must mimic something to make its point.

The Court seems torn. At oral argument, some of the Justices appeared persuaded by Goldsmith’s warnings about art’s ambiguity. Justices Alito and Kagan, for instance, were skeptical of how plainly Warhol’s team had framed the message of the prints. “You make it sound simple,” Alito said, “but maybe it’s not so simple, at least in some cases, to determine what is the meaning or the message of a work of art.” Justice Kagan wondered if the Warhol case benefited from a “certain kind of hindsight,” since “now we know who Andy Warhol was and what he was doing and what his works have been taken to mean,” knowledge we might not have had when he was starting out.

At the same time, other Justices seemed more comfortable interpreting Warhol’s works. Justice Sotomayor took it for granted that Warhol’s works commented on Prince’s “superstar status” and “his consumer sort of life.” The idea that Warhol’s art depicted the flattening of celebrity was repeated so many times over the course of the morning that it flattened out, too. Justice Kagan recognized that Warhol “took a bunch of photographs and he made them mean something completely different.” Even Chief Justice Roberts repeated, rather uncritically, the foundation’s view that Warhol sent a “message about the depersonalization of modern culture and celebrity status and the iconic” and showed “a particular perspective on the Pop era.”

These comments suggest that at least some of the Justices may reject the lower court’s decision against Warhol, which was based on the idea that judges couldn’t, or shouldn’t, make judgments on art. But they also expose an irony at the heart of this case. A win for Warhol would protect an artistic tradition dedicated to exposing the artifice of authorship and the slipperiness, or absence, of meaning. “If you want to know all about Andy Warhol,” the artist once said, “just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.” Warhol also said that his art was “junk” and that he liked repetition because “the more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away and the better and emptier you feel.” But to prove that his prints say something different than the Goldsmith pictures, Warhol’s foundation has distilled from them a single, settled, unsubtle message about celebrity and consumerism. If the Court sides with Warhol and dismisses Goldsmith’s view that the meaning of art is too unstable to support a legal standard, the outcome will be paradoxical—a boon for art that borrows, grounded in a rejection of the very ideas this art raises.

Inviting judges to interpret art risks infecting legal judgment with the kind of personal predilections that are supposed to stay off the bench. Justice Roberts once compared judges to umpires—and decoding prints is far from calling a ball or strike. But judges hardly abstain from the world of meaning and values. When the lower court found that judges could not consider a work’s message, it sent its own messages: that the meaning of art is too subjective to pin down, that collages are the only valid form of borrowing, that appropriative art isn’t worthy of copyright’s protection. The Justices may be tempted, as that court was, to avoid making judgments that fall outside the letter of the law, but they’ll be making them anyway. We can only hope that we don’t lose Pop Art along the way.