In February 1977, the Brooklyn-based artist Marilyn Nance was waiting on the airport tarmac in Lagos, wearing a white graphic tee that read “Okra is an African Word,” though in the image of her taken that day it is partially obscured. Fastened to her broad-rimmed straw hat is a sheet of paper on which the word “standby” had been hastily handwritten. She had just spent a month in the newly oil-rich Nigeria photographing and documenting a singular historical event: the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture. FESTAC ’77, as it is also called, gathered more than 15,000 writers, artists, performers, dramatists, filmmakers, musicians, philosophers, poets, activists, spectators, and scholars from over fifty-five countries. It was a colossal transnational spectacle, largely financed by Nigeria’s military government, with the aim of extending the aesthetics of Pan-African freedom that had been developed at the First World Festival of Black Arts (FESMAN, or Festival Mondial des Arts Nègres) in Dakar in 1966.

Two contingents from the North American Zone traveled to Lagos, and each stayed two weeks. When Nance, attending as part of the United States delegation, decided to stay for the duration of the festival, she didn’t have any guarantee that she would have a seat on the second official plane back to New York City. “Everybody remembers me as this crazy girl,” she told the scholar and curator Oluremi C. Onabanjo. She rode back to FESTAC Village on a motorcycle, cementing what Onabanjo calls her “special” position as “an American who experienced the entirety of FESTAC ’77 in Lagos.” She was twenty-three.

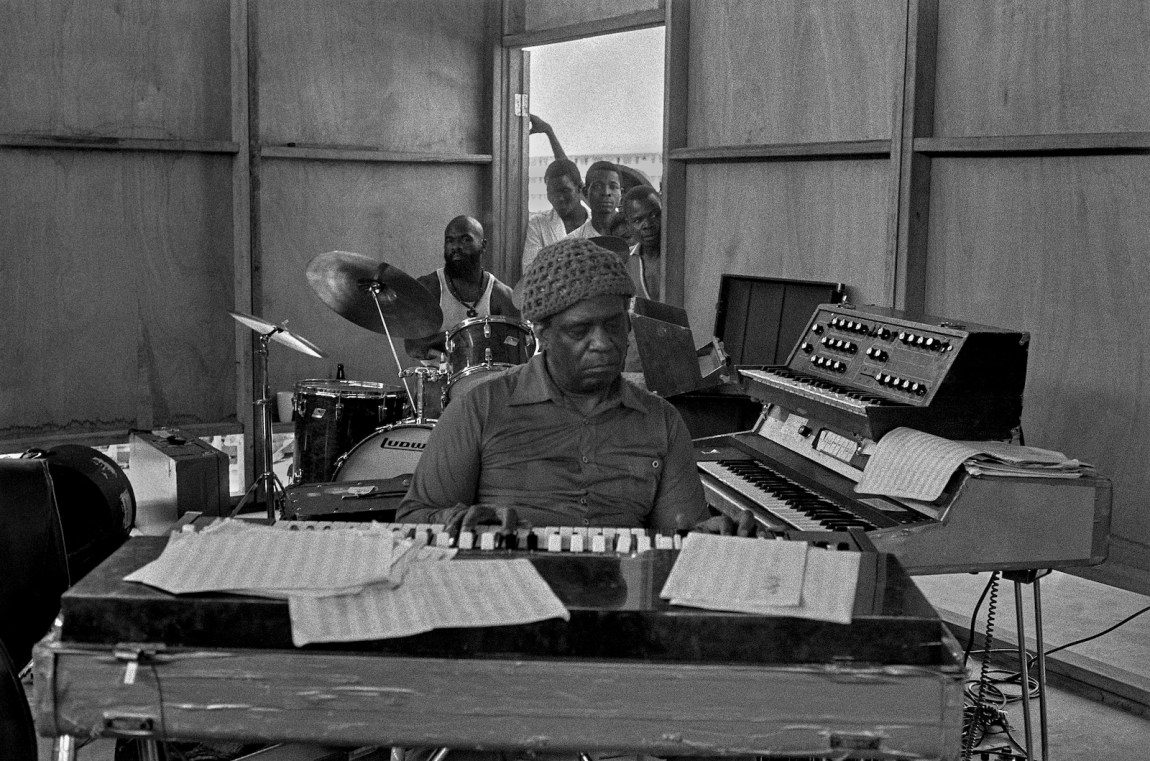

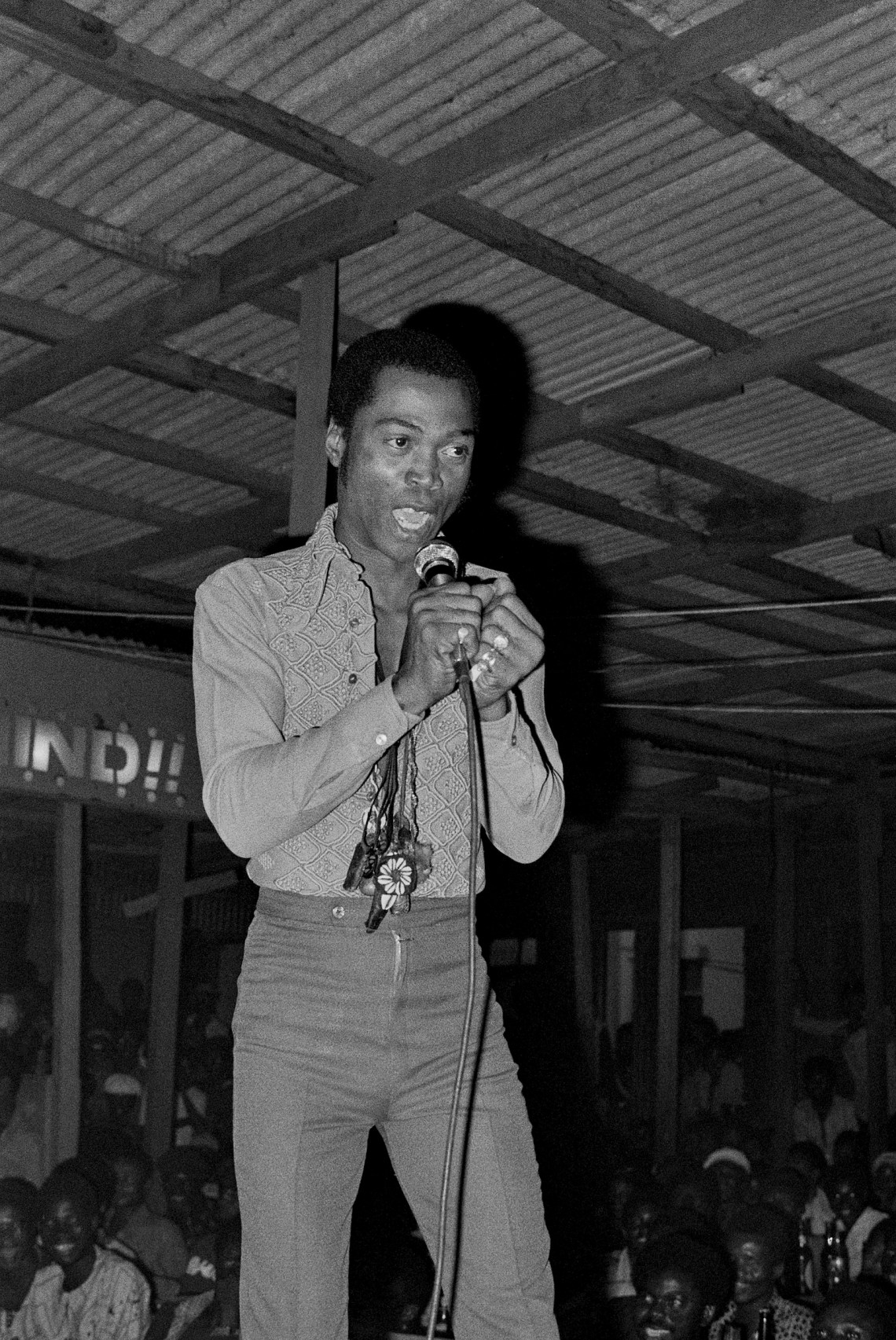

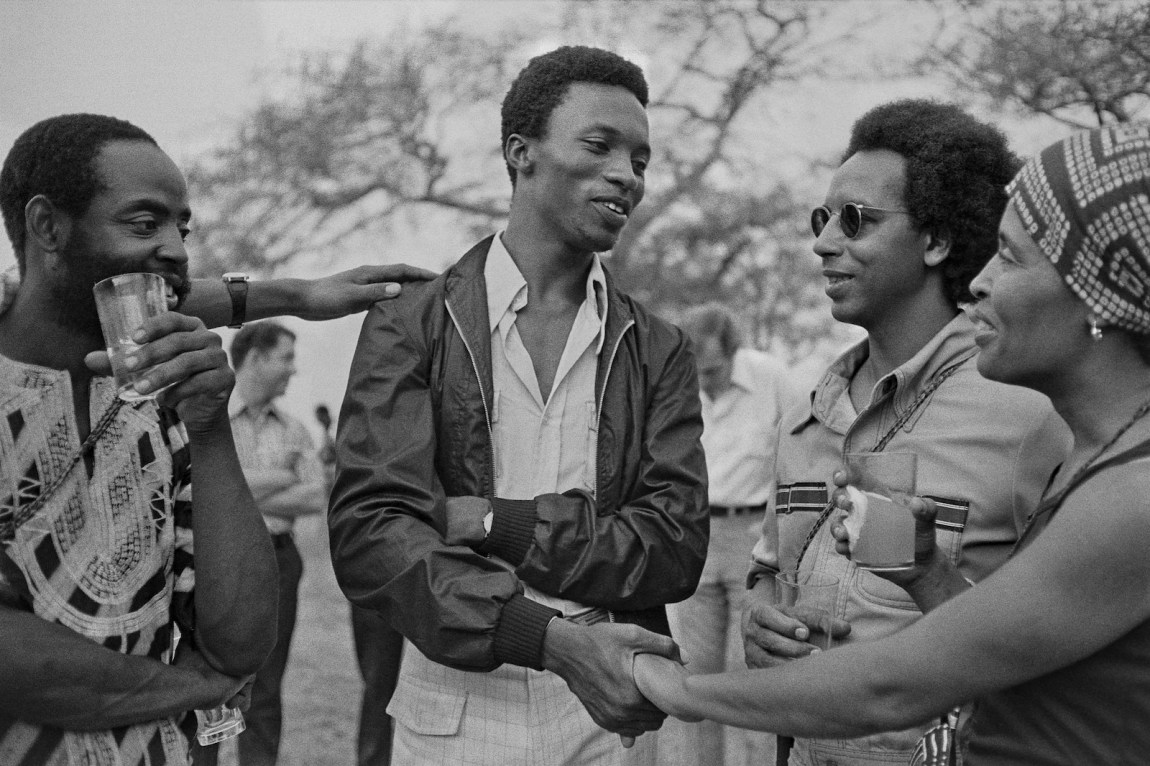

A new monograph, Last Day in Lagos, gathers a selection of Nance’s brilliantly unhurried photographs of the festival attendees—many published here for the first time. She took pictures of the most famous guests, including Audley “Queen Mother” Moore, Stevie Wonder, Ellsworth Ausby, Sun Ra, and Miriam Makeba. Even Louis Farrakhan, shaking hands with Samella Lewis, appears without his usual sense of charismatic self-aggrandizement. But most of the pictures show unnamed participants, clouds of anonymous moving bodies. In addition to more than a hundred of the photographs from FESTAC (she took over 1,500), the book includes a far-reaching interview with Nance conducted by Onabanjo, the volume’s editor, from 2017 to 2020.

Last Day in Lagos contains no photographs of Nance on her first day in Nigeria, which was also her first day on the continent and her first day outside the United States. She describes that simultaneous experience of flight and myth of homecoming, instead, in fewer than a hundred words: “I went to Nigeria thinking, I’m an African person. I’m removed from the continent, but here I am, returning. But, when I arrived, I realised that we weren’t seen as African people. We were seen as Americans. That was the first time I ever really felt myself as an American.”

Nance’s insights reflect a diasporic debate—over who can claim Africa, what home is, and the imperial hegemony of the US tourist gaze—that still haunts black politics. About those demands of diasporic propinquity, she has the literal and figurative last word. “These images of time and place reflect my romantic notions of Pan-African unity, my nostalgia for this incredible celebration of world culture, and hint at the terrors to come after the festival’s end,” she writes in an afterword. The interview intimates those terrors, burying one in a footnote. The Nigerian superstar Fela Kuti, we learn, criticized the festival and held a “counter-FESTAC” at his club, Shrine. “On 18 February 1977,” the footnote reads,

1,000 Nigerian soldiers stormed and destroyed Kuti’s compound, The Kalakuta Republic, located at 14A Agege Motor Road in Surulere, Lagos. During the skirmish, Kuti was beaten unconscious, as were many of his bandmates and staff. Kuti’s seventy-seven-year-old mother, Funmilayo Thomas Ransome-Kuti was thrown out of a first-floor window, breaking her leg.

She would die the next year due to complications from the injuries she sustained that day.

There were also other losses, most of them unprocessed and unmetabolized, and there are always other dispossessions. There were supposed to be more FESTACs, the next one planned for Ethiopia in 1981. But FESTAC ’77 turned out to be the effective end to decades of Pan-African events, including many Pan-African Congresses, the Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers in 1969, and the First Congress of Black Writers and Artists in Paris in 1956. From the beginning, FESTAC was a contested project both in Nigeria and beyond. There was much debate about the festival’s aims and means—exemplified by the chasm between the priorities of Nigeria’s head of state, Lieutenant General Olusegun Obasanjo, who wanted economic opportunity, and those of the Senegalese president and major Négritude intellectual Léopold Sédar Senghor, who championed what he called “libération culturelle.” Another well-recorded division was over the distinction between “African” and “Black,” and by extension over the inclusion of participants from North Africa. FESTAC called itself “Black and African” where FESMAN, a decade earlier, had called itself simply Nègre. This shift reflected diverging goals: Did “black” signify a global race-based consciousness or African unity?

Advertisement

The record of this period of vitality is itself a photographic blur, a muddled account of rapid movement in the face of the promises and failures of national independence. “FESTAC ’77 was a peak Pan-Africanist experience, but it also appeared to be a tipping point,” writes Uchenna Ikonne in “Sounds on the Ground,” an essay first published by the Red Bull Music Academy in 2017 and included in Last Days in Lagos. “After 1977 the movement began to decline in popular culture, replaced by a slicker, more consumerist aesthetic.” In her essay for the volume, “Time Travel,” Tsitsi Ella Jaji puts it this way:

Whither Pan-Africanism? One answer would be, where it always was—in the liminal space of arrivals and departures, greetings and goodbyes. The doors of no return that led captive Africans into the Middle Passage have become one such paradigmatic portal, a necessary reckoning with the scars of slavery on both sides of the Atlantic.

Last Day in Lagos joins recent cultural, political, and literary reevaluations of FESTAC, notably the Cape Town–based periodical Chimurenga’s collection FESTAC ’77: 2nd World Festival of Black and African Arts and Culture (2019), a labyrinthine patchwork of photographs (including some by Nance), archival documents, and new commissioned essays. The book, “decomposed an-arranged and reproduced” by Chimurenga, is twice the size of the sleek, compact Last Day in Lagos. In part thanks to its collagelike form, it captures the range of intellectual discussions and political debates that normally get glossed over in favor of a single narrative of Pan-African grandeur. And while Last Day in Lagos’s publication date—October 1, 2022—might on the surface seem to channel excitement over Nigerian Independence Day and FESTAC’s forty-fifth anniversary, the intimate publication has a similarly polyphonous effect as Chimurenga’s, immersing the reader in Nance’s archive as though it were an unfinished sentence, an elaborate thought trailing off.

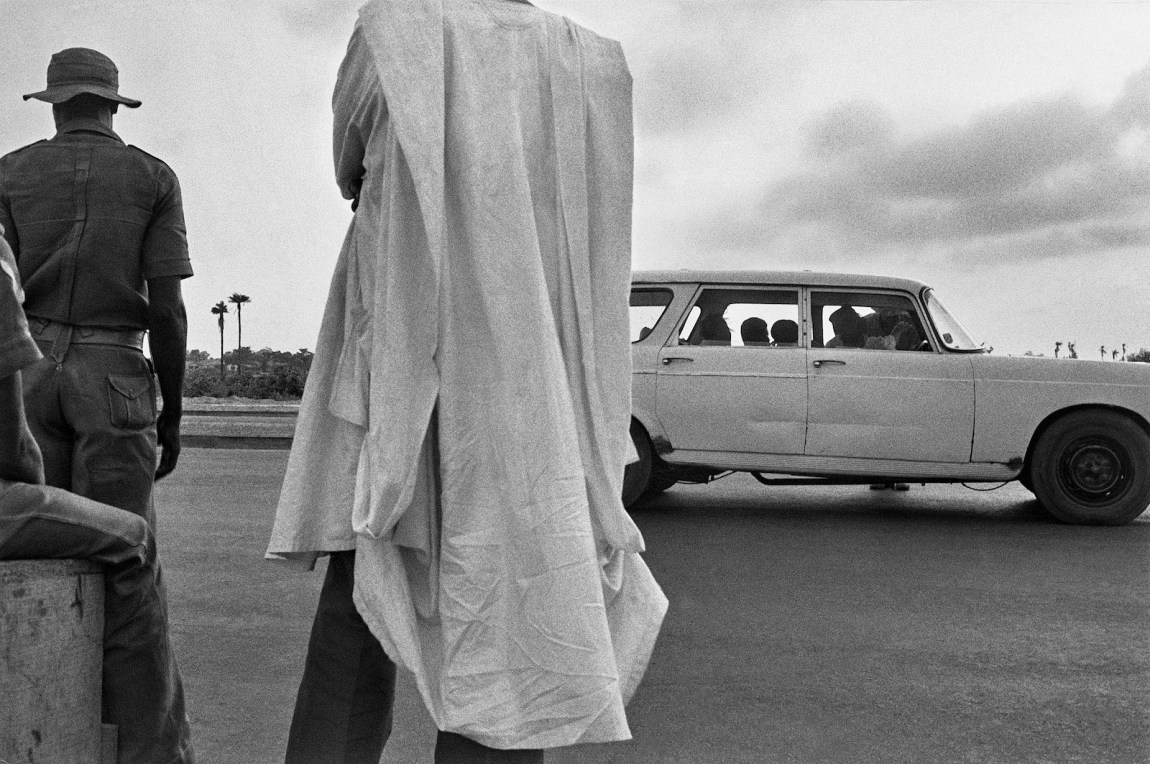

Each image takes its own time. Nance’s signature style at FESTAC, if it can be pinned down, might be said to involve bustling scenes marked by a certain detail or posture that seems out of place with its surroundings. A toddler stands among adult legs as among trees, looking down and dressed, sinisterly, as Obasanjo. The artist Viola Burley appears dressed in a headwrap, one hand folded and the other with a cigarette, slightly obscuring her face. Taken at a FESTAC reception at the residence of the US ambassador to Nigeria, Donald B. Easum, this photograph—a headstrong woman in the front, suited-up men in the background—suggests a symbolic reversal of the predictably masculinist gender dynamics at play in 1970s black intellectual life. Two members of the acrobatic troupe Flying Souls Trapeze, subdued and paused, soar in midair. Only the sky is behind them, swarmed by a web of ropes. If a circus act is the epitome of high-profile revelry and exhibitionism, Nance has made a photograph that almost seems to sigh.

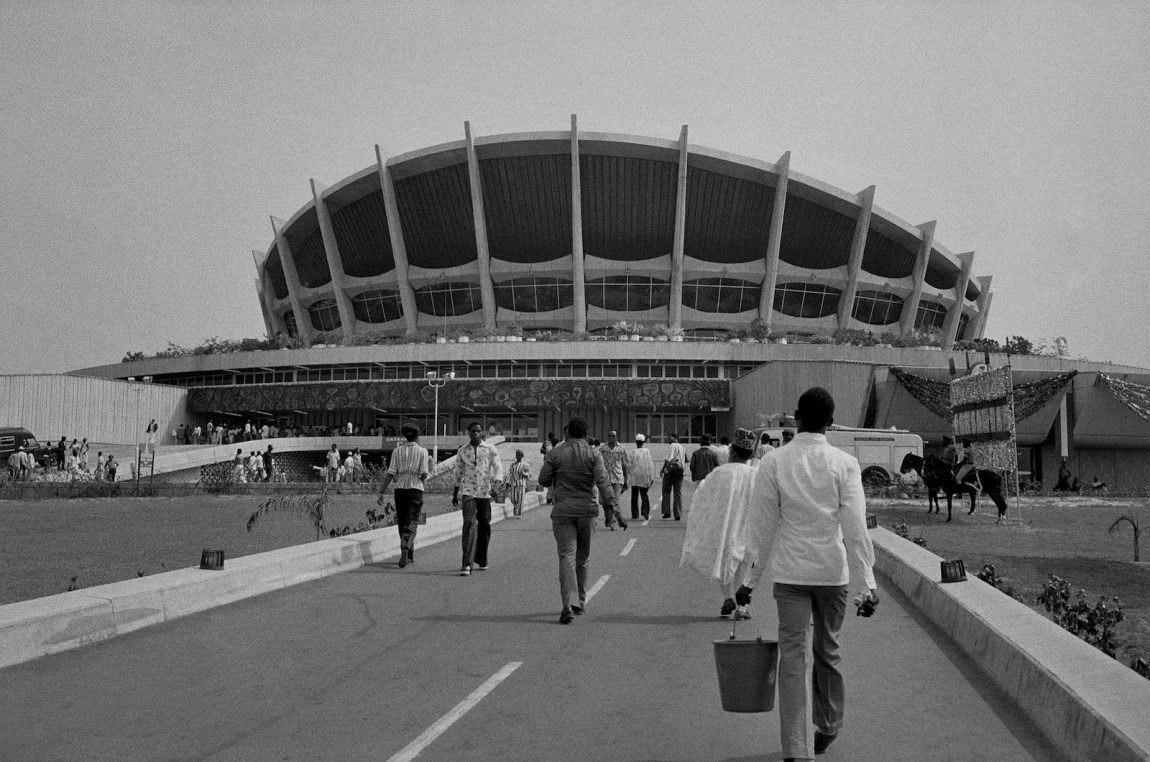

On that word “circus.” It is used twice in Ikonne’s essay, to mark the difference between the 1977 event and FESMAN, “a relatively low-key highbrow conference,” and then to describe the “circus of spending” in Nigeria, which had joined OPEC in 1971. FESTAC had been postponed twice. The first delay was due to the brutal civil war between the Nigerian government and the secessionist state Biafra, in the eastern region, in which approximately two million people were killed or died of starvation between 1967 and 1970. The second was because the massive construction projects built for the festival—new roads, superhighways, a housing estate for participants, hotels, and the National Arts Theatre—took longer than planned.

Critics, including Kuti, lambasted the festival’s opulent budget, which they considered emblematic of state corruption and repression. And so FESTAC symbolized both the coming of the popular and the neglect of the masses. A few of Nance’s black-and-white photographs carry only the traces of sentient existence—yams, mattresses, a generator at FESTAC Village, architectural structures—but most are of people: during the opening ceremony, people holding flags and signs; a breathtaking crowdscape at Nigeria’s National Stadium; an ensemble of anonymous faces looking into, beyond, and against the camera. Light shifts and sound echoes. Last Day in Lagos leaves the captions till the end, further minimizing the distinctiveness of any single participant.

Advertisement

Despite all the pomp and circumstance, Nance managed to capture moments of reprieve. Where one could have seen trophies and formalities, she sees the befores and afters. She practices photography not as objective photojournalism but as something closer to poetry in its attention to the play between movement and pause, dodging the myths of precolonial cultural stasis that were so dominant in the national Nigerian narrative. Nance’s process was immersive. “I actually photographed a lot of photographers. I noticed that some would find a position on the field, and they would stay there, photographing contingents as they passed by,” she tells Onabanjo. “But I was mobile. I would move with one contingent, and then I’d move with another. I guess I was a little bit of a renegade, but that worked for me.”

She refuses to distinguish between what is in the frame and what is beyond it, what is behind the camera and in front of it. “When looking at my own work, I see that I was in the crowd. I was part of the whole thing,” Nance says.

I don’t call it capturing an image. I don’t call the people in front of me my subjects. We have to check the language that we use around photography. I don’t shoot, I make images. I’m so much a part of the images that I make, that I become invisible, which is quite a good thing, and quite a bad thing, depending on how you look at it.

In her photographs of melees, the motley crews scan Nance just as much as she scans them. Every photograph and gesture indexes what cannot be included in the frame. As the journalist Antonio de Figueiredo wrote of FESTAC, “It was in fact so big an enterprise that no single individual can claim to have seen more than a part of what went on.”

“It’s hard to describe,” Nance tells Onabanjo, “and people have positioned it as science fiction, but it really did happen.” Insisting on FESTAC as fact, Nance gazes askew at such cosmopolitan celebrations of a conception of blackness that can reveal itself as a phantasm under the weight of the present. It is a testament to her art that she illuminates FESTAC not only as national euphoria or Pan-African emancipation but also as a concrete, exceptional, oil-fueled historical event with its own excess, mayhem, disappointments, contradictions, and alienations.